Forte Spagnolo: A Historic Spanish Fortress in L’Aquila, Italy

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.5

Popularity: Medium

Official Website: www.museiitaliani.it

Country: Italy

Civilization: Early Modern, Modern

Site type: Military

Remains: Fort

History

Forte Spagnolo is a fortress located in L’Aquila, Italy, constructed by the Spanish during their domination of southern Italy in the early 16th century. Its creation reflects the military and political strategies imposed upon the city during a period of conflict over control of the Kingdom of Naples.

The origins of the site trace back to an earlier fortification known as Castellina, built in 1401 by King Ladislaus I. This small fortress occupied the highest point along the city walls and served as a defensive position before the construction of the larger fortress. The decision to replace Castellina was driven by the Spanish viceroys seeking to strengthen their hold over L’Aquila after the city sided with the French in regional disputes.

In 1527, the Spanish viceroy Filiberto d’Orange ordered the replacement of the older fortification with a new and more formidable structure. Actual construction began in 1534 under the direction of the viceroy Pedro Álvarez de Toledo y Zúñiga. The project was initially supervised by Pedro Luis Escrivà, a Spanish military engineer renowned for his expertise in firearms and fortification. After his tenure ended in 1537, Gian Girolamo Escrivà took over until 1541. The fortress was financed largely through high taxes levied on L’Aquila’s population, which led to economic difficulties in the city.

Construction ceased in 1567 before the fortress was fully completed, finishing only the military facilities necessary for its operation. The structure was specifically designed with its artillery facing inward towards the city, as its primary purpose was to control and suppress potential uprisings rather than defend against foreign assaults.

Throughout the 17th century, Forte Spagnolo transitioned from a purely military role to serve as the official residence of the Spanish governor overseeing the city. In subsequent centuries, it housed various foreign troops: French soldiers in the 18th century, followed by German forces during the Second World War. During this latter occupation, the fortress sustained considerable damage.

Following World War II, the fortress was transferred from military to cultural authorities and underwent restoration between 1949 and 1951. It was then repurposed as the home of the Museo Nazionale d’Abruzzo, preserving and exhibiting the region’s history and art. Earlier, in 1902, the site had already been declared a national monument in recognition of its historic value.

In 2009, a strong earthquake severely damaged the fortress, particularly affecting the upper floors and the bridge crossing the dry moat. Restoration efforts began in 2011 and have continued into the present decade. To compensate for the loss of the original concert hall located inside the fortress, a temporary auditorium designed by architect Renzo Piano was erected in the nearby park in 2012.

Remains

Forte Spagnolo exhibits a distinctive square layout measuring approximately 130 meters on each side, constructed with Renaissance-era military engineering principles. Four massive bastions, shaped like lance tips, anchor each corner of the fortress, oriented toward the cardinal points to maximize defensive coverage. These bastions operate as independent units, each containing two vaulted casemates with circular openings that allowed smoke from firearms to escape, demonstrating an advanced understanding of battlefield conditions. Each bastion was also equipped with its own water cistern, ensuring self-sufficiency in the event of a siege.

The fortress walls rest upon solid rock, with their base thickness reaching up to 10 meters, tapering to about 5 meters at the summit. The exterior surfaces are clad in travertine stone, sourced from a nearby hill that was leveled specifically for building material. This choice of durable local stone contributes to the fortress’s imposing and lasting presence.

A notable architectural innovation is seen in the way the bastions connect to the curtain walls through double protrusions. This feature effectively doubled the number of firing positions, enhancing flanking fire capabilities while reducing the fortress’s exposure to enemy artillery attacks. Surrounding the entire structure is a broad, deep dry moat about 23 meters wide and 14 meters deep, which was designed to keep enemy artillery at a safe distance from the walls. Access across the moat was originally granted by a wooden retractable bridge, replaced in 1883 by a more permanent stone bridge.

The main entrance stands out as a decorated portal crafted from white stone. It features Doric pilasters on either side and is crowned with the double-headed eagle symbol associated with the House of Austria. A Latin inscription above the portal reads “AD REPRIMENDAM AUDACIAM AQUILANORUM,” which translates to “To repress the audacity of the Aquilans,” reflecting the fortress’s role as a tool of political control. This entrance was likely designed by the fortress’s initial architect, Escrivà, and executed by local sculptors Salvato Salvati and Pietro Di Stefano, himself illustrating the integration of local artistic tradition into the fortress’s fabric.

Inside, the fortress encloses a square courtyard. On the southeast side, the entrance side, there is a double-order colonnaded portico. This architectural feature was originally intended to surround the entire courtyard, yet the extension remained unfinished. Beneath the surface, an elaborate system of underground tunnels and countermines extends beneath the bastions. These subterranean passages were built to detect and neutralize any enemy attempts at undermining the walls. Portions of this underground network also served as prison cells during the fortress’s use as a place of suppression.

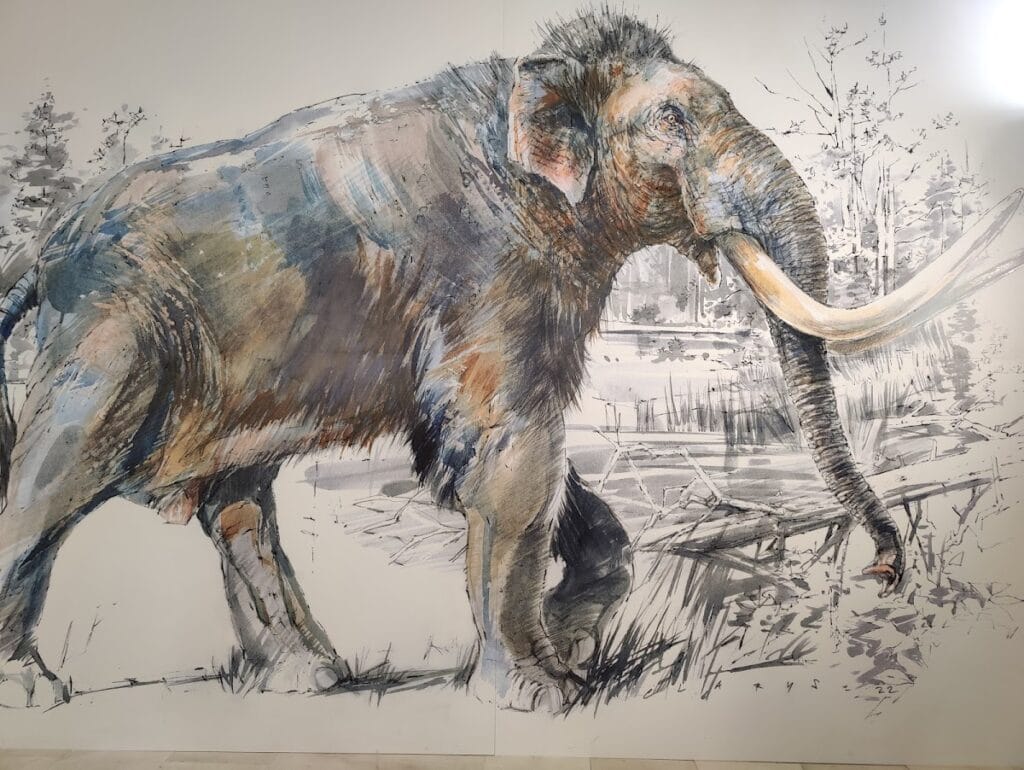

Within the underground chapel, unique climatic conditions led to the natural mummification of hundreds of bodies. Today, four of these mummies are preserved in a partially glazed container on display inside the fortress, providing a rare glimpse into the site’s historical use and environment.

The fortress’s water supply system demonstrates deliberate planning to ensure its autonomy. The city’s aqueduct was diverted to supply the fortress first, enabling the occupants to maintain water access while withholding it from the city during times of rebellion. Additionally, the fortress’s cannons were cast using metal from the city’s church bells, a detail highlighting the economic sacrifice imposed on the population.

Currently, Forte Spagnolo hosts the Museo Nazionale d’Abruzzo, which utilizes three floors to exhibit archaeological finds, medieval artworks, and contemporary pieces. The complex also includes a modern auditorium and conference facilities. Surrounding the fortress lies the Parco del Castello, a large park filled with trees that serves as a green space around the historic stronghold.