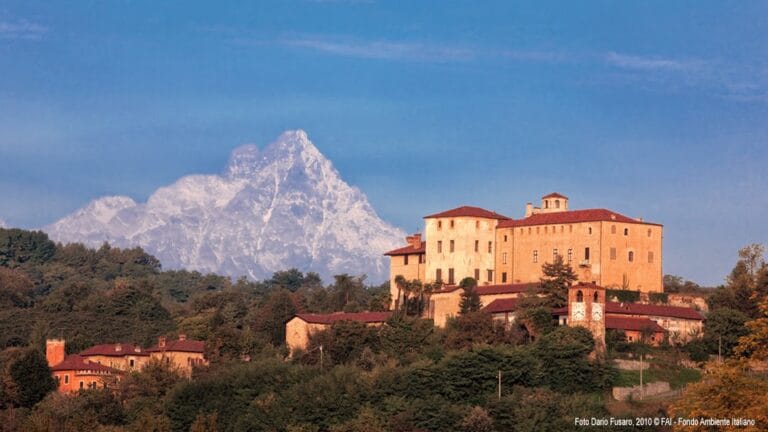

Castello di Villanova Solaro: A Medieval Fortress in Italy

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.5

Popularity: Low

Official Website: www.castellodeisolaro.it

Country: Italy

Civilization: Early Modern, Medieval European, Modern

Site type: Military

Remains: Castle

History

The Castello di Villanova Solaro is situated in the municipality of Villanova Solaro, Italy. It was originally built during the medieval period as a fortress to serve the territorial interests of regional powers in northwestern Italy.

The castle’s earliest record dates to 1259, when it was known as “Castrum Villanove.” Positioned on the contested border between the Principality of Acaja and the Marquisate of Saluzzo, the fortress was a key military outpost amid ongoing conflicts that lasted until the early 17th century. In 1295, Filippo di Savoia, Prince of Acaja, undertook a reconstruction after receiving the castle from his uncle, Amedeo V, reinforcing its defensive capabilities against rival forces.

Throughout the 14th century, the castle changed ownership multiple times, reflecting the shifting political landscape. After passing briefly to the Marchesi del Carretto in 1332 and the Falletti family in 1335, it returned to the Acaja family in 1336. By 1362, the feudal rights were sold to the Solaro family, an old noble house from Asti. This family’s influence was significant enough that following the unification of Italy, the surrounding town adopted the name Villanova Solaro in their honor.

The castle remained militarily active into the late 15th century. During the 1486 conflict between the House of Savoy and the Marquisate of Saluzzo, it housed heavy artillery preparing for Savoy’s conquest of Saluzzo the following year. In 1501, the fortress provided shelter to troops allied with French King Louis XII and Emanuele Filiberto II, demonstrating its ongoing strategic role amid wider European power struggles.

Adaptations to changing warfare occurred in the 16th century, when Bartolomeo Solaro modified the castle to better withstand gunpowder artillery. His work included lowering the height of the main tower and removing the defensive moat, reflecting evolving military technology. After the Treaty of Lyon in 1601 resolved the border disputes, the castle lost its military importance and gradually transitioned into a more residential and leisure function under Solaro ownership.

In the early 19th century, Countess Eufrasia Solaro, the last of her line, made significant changes. She demolished the eastern wing and two towers and transformed the area into a landscaped park, building a brick wall from the reused materials to enclose the grounds. The castle enjoyed cultural prominence when in 1831 it hosted the Italian patriot Silvio Pellico, who read passages from his influential memoir “Le mie prigioni” within its walls.

Ownership and use shifted again in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1899, Cesare Vitale donated the castle to serve as a hospital for chronically ill poor residents, named the Vincenzo Ferreri Hospital, which operated from 1908 to 1927. Later, the building functioned as a school and community center until its closure in 1985 due to deterioration. Restoration efforts in the 1990s returned the castle to private ownership, leading to its current use primarily as an event venue.

Remains

The castle’s original design followed a square plan featuring four corner towers that projected outward, surrounded by a wide moat crossed by a drawbridge. This strategic layout allowed defenders to target assailants even if they gained access to the moat area. Today, only two of these towers survive. The tallest, once about 30 meters high and serving as a lookout post, was lowered by approximately one-third in the 16th century to mitigate artillery risks introduced by gunpowder weapons. The eastern wing and two towers were removed in the early 1800s, with their bricks repurposed to construct a brick wall that still encloses the castle park.

Internally, the castle features a variety of historically significant elements. A marble plaque commemorates Silvio Pellico’s stay, while a private chapel displays a fresco portraying the territories under the Solaro family alongside Monviso mountain. The “Sala delle Battaglie” (Battle Hall) functions as a museum exhibiting a collection of arms including armor, crossbows, axes, and halberds. Its ceiling is adorned with painted battle scenes that emphasize the castle’s martial heritage.

Prominent coats of arms decorate the main corridor, representing the Ronco, Acaja, Savoia, and Sandrone families. This passageway has a distinctive 15th-century hand-cut stone tile floor known as “Barzolina.” The “Sala Filippo d’Acaja” on the north side contains 18th-century frescoed wooden ceiling panels resting upon 14th-century walnut wood paneling. This room historically served as the baronial reception and dining hall.

Nearby is the “Sala Verde,” a small vaulted chamber with 15th-century frescoes rendered in gray tones, overlooking the surrounding park. On the south side lie the “Silvio Pellico Rooms,” where the patriot stayed and read his famous writings. These walnut-paneled rooms also housed the book collection of Countess Eufrasia and contain recently uncovered 15th-century frescoes illustrating symbols linked to the Marquisate of Saluzzo.

The original courtyard featured a three-story portico decorated with frescoes and supported by columns. However, this was closed off in the 16th century by Bartolomeo Solaro and, more recently, covered by a modern glass, wood, and steel structure measuring over 20 meters long and 6 meters high. This enclosed space now serves as a venue for large gatherings.

Beneath the Pellico Rooms lie vaulted stables from the 1500s known as the “scuderie dei cavalieri.” Initially submerged by the castle moat, these spaces were later used as animal stables until World War II. Excavations during the 1995 restoration exposed them anew. A sealed chamber within the structure appears on historic maps but remains inaccessible for safety reasons.

The castle’s park covers around 15,000 square meters today, down from 35,000 square meters at its peak under Countess Eufrasia. Its boundaries are marked by the brick wall constructed from dismantled castle sections. The grounds include large parking spaces, a soccer field, and the local elementary school. The central avenue in the park features 34 linden trees replanted during the 1995 restoration to restore the 19th-century design first created by Countess Eufrasia. During World War II, most of the original linden trees were cut, save for two centuries-old specimens.

Inside the castle’s walls, a small artificial pond and a remaining water channel serve as reminders of an earlier stream that once supplied water for the moat and for laundering clothes. Carved stones shaped to support individuals while washing persist near this channel. The modern fountain at the center of the park’s main avenue, along with four large marble statues symbolizing the seasons, was installed as part of the recent restoration efforts. Several amphorae and smaller sculptures dispersed throughout the grounds complement this historical landscape, which mainly features native species such as linden, oak, walnut, elder, and acacia, alongside some non-native trees introduced in the 1960s for forestry grants.