Wroxeter Roman City: A Roman Settlement and Early Medieval Site in the United Kingdom

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.5

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.english-heritage.org.uk

Country: United Kingdom

Civilization: Roman

Remains: City

History

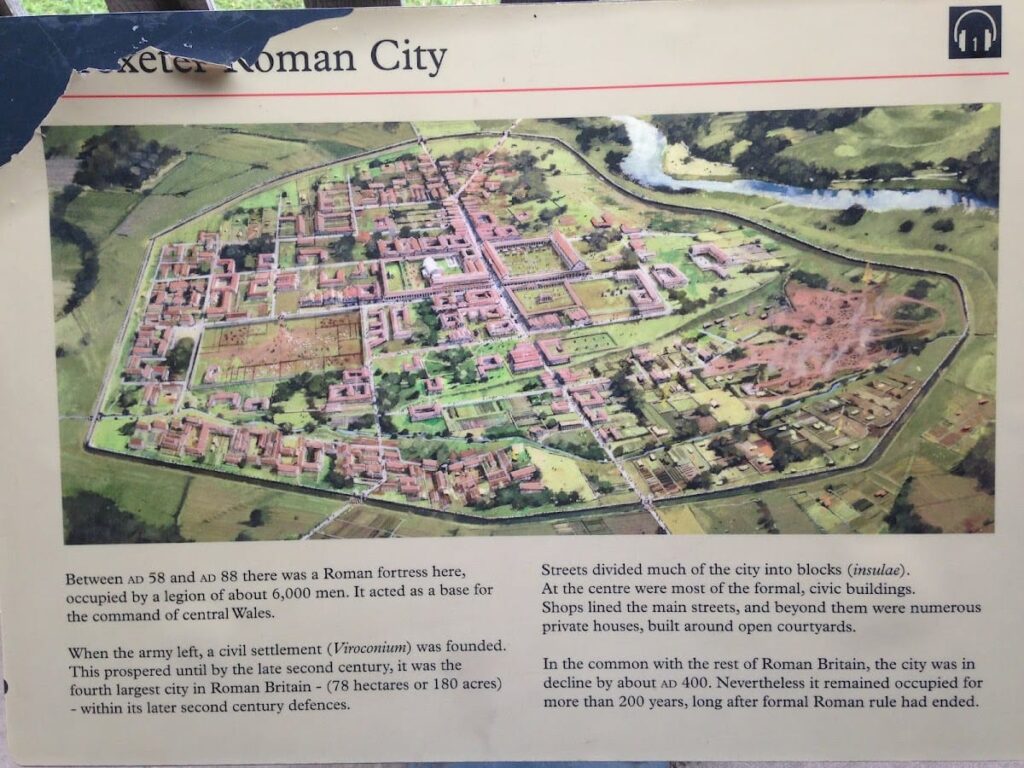

Wroxeter Roman City, located near Shrewsbury in the United Kingdom, was originally established by the Romans during their early conquest of Britain. Known then as Viroconium Cornoviorum, it began as a frontier fort for a unit of Thracian auxiliary soldiers under the command of Governor Publius Ostorius Scapula. The site was strategically placed near the end of Watling Street and close to a crossing of the River Severn.

In the mid-1st century AD, the fort was taken over by the Roman legion Legio XIV Gemina, and later by Legio XX Valeria Victrix. The military presence ended by the late 80s AD when the legion moved to Deva Victrix, now Chester. After the army left, the civilian settlement, originally housing soldiers’ families and support staff, expanded into a planned town. A street grid was laid out, and a colonnaded forum was constructed over an unfinished legionary bathhouse. This forum was completed around 130 AD during the reign of Emperor Hadrian, who is commemorated by an inscription found on site.

Viroconium grew to cover more than 173 acres (70 hectares), becoming the fourth largest Roman settlement in Britain. Its population likely exceeded 15,000 people. Despite its location on the empire’s frontier, the town was wealthy and featured public buildings such as baths, temples, and shops. Between 165 and 185 AD, the forum was destroyed by fire but was rebuilt with some changes to its design.

Following the end of Roman rule around 410 AD, the local Cornovii tribe divided, and Viroconium became the early sub-Roman capital of the kingdom of Powys. It was associated with the Wrocensaete sub-kingdom and is believed to be the city referred to as Cair Urnarc or Cair Guricon in the medieval Welsh text Historia Brittonum. A significant artifact from this period is the Wroxeter Stone, inscribed in a partly Latinized form of Primitive Irish and dated between 460 and 475 AD, showing early medieval cultural connections.

Between 530 and 570 AD, the site underwent a major rebuilding phase. The old Roman basilica was replaced by timber-framed buildings constructed using Roman measurements. This work may have been directed by church authorities. This community lasted for about 75 years before gradually being dismantled. The site was likely abandoned peacefully in the late 7th or early 8th century, coinciding with the rise of the Anglian Wreocensæ te and the relocation of Powys’s royal court to Mathrafal.

Archaeological interest in Wroxeter began in the 19th century and has continued since, revealing extensive remains of its Roman and post-Roman past.

Remains

Wroxeter Roman City was laid out with a clear street grid typical of Roman urban planning. The town covered approximately 78 hectares (173 acres) at its height, with foundations of hundreds of buildings preserved beneath the surface. These have been mapped through aerial surveys and geophysical methods.

One of the most prominent surviving features is known as “The Old Work,” which includes a large archway and part of the frigidarium, or cold room, of the Roman baths. This structure stands about seven meters high and is the largest free-standing Roman ruin in England.

Excavations have uncovered a large baths complex equipped with underfloor heating, dating from the 2nd century AD. Adjacent to the baths was a small marketplace. The forum, or basilica, built in the 2nd century, was colonnaded and constructed over an unfinished legionary bathhouse. It bears a dedicatory inscription to Emperor Hadrian.

Many buildings were constructed using stone and brick, with decorative features such as tessellated (mosaic) pavements and plaster vaulting. Numerous small finds include jewellery, medical instruments like surgical probes, and religious items such as over 100 votive plaster eyes and clay figurines of the goddess Venus. These objects provide insight into the religious practices and daily life of the inhabitants.

Later, many monumental Roman buildings were quarried for stone to build local churches, but some structures remain visible and accessible. Organic remains, including coprolites (fossilized feces), have been found, offering information about diet and health.

A reconstructed Roman villa on the site, built using authentic ancient techniques under the supervision of archaeologist Dai Morgan Evans, demonstrates private residential architecture from the later Roman period. This reconstruction helps illustrate the construction methods and living conditions of the time.