Susa: A Roman Municipium in the Piedmont Region of Italy

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.6

Popularity: Very Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Country: Italy

Civilization: Byzantine, Roman

Remains: Burial, City, Civic, Domestic, Economic, Entertainment, Infrastructure, Military, Religious, Sanitation

Context

Susa is situated in the Susa Valley of the Piedmont region in northwestern Italy, near the contemporary town of Susa within the Metropolitan City of Turin. The site occupies a strategic position along the Dora Riparia river, nestled between the Cottian Alps. This mountainous corridor historically served as a vital passage connecting the Italian peninsula with transalpine territories, influencing settlement patterns and facilitating movement through the Alpine environment.

Archaeological evidence demonstrates continuous human presence at Susa from the Bronze Age through the Roman period. Initially inhabited by Ligurian groups, the area later came under the control of the Celtic Taurini tribe before incorporation into the Roman state. The site’s location near key mountain passes and water resources shaped its development as a municipium during the Roman Imperial era. Excavations have revealed stratified occupation layers, though the decline and eventual abandonment of the settlement after late antiquity remain insufficiently documented.

Systematic archaeological investigations began in the 19th century, uncovering structural remains and material culture that illuminate the site’s long-term evolution. Preservation efforts focus on safeguarding exposed ruins within the modern urban context, although environmental factors and urban expansion continue to challenge the conservation of archaeological deposits.

History

Susa’s historical trajectory is closely linked to its position within the Susa Valley, a key Alpine corridor facilitating connections between Italy and transalpine regions. The site exhibits a sequence of occupation from the Bronze Age through the Roman period, reflecting shifts in cultural and political control from indigenous Ligurian populations to Celtic groups and ultimately Roman administration. Its development mirrors broader regional dynamics, including Roman expansion into northern Italy and the integration of Alpine territories into imperial structures. Although urban activity diminished after the late Roman period, the precise reasons for this decline remain unclear due to limited archaeological evidence.

Bronze Age and Pre-Roman Period

During the Bronze Age, the Susa Valley was inhabited by Ligurian communities who established settlements exploiting the valley’s natural resources and strategic location. Archaeological data, though limited, indicate continuous occupation throughout this era. By the late Iron Age, the region came under the influence of the Celtic Taurini tribe, who controlled much of the surrounding Alpine area. This is corroborated by archaeological finds such as pottery and metalwork, as well as classical literary sources that reference the Taurini. Susa thus formed part of a network of transalpine Celtic settlements prior to Roman conquest.

Roman Period

The Roman Republic extended its dominion over the Susa Valley in the late 2nd to early 1st century BCE, incorporating Taurini territory as part of its efforts to secure Alpine passes and consolidate northern Italy. This expansion was critical for controlling transalpine routes and facilitating military and commercial movement. Under the Roman Empire, Susa was granted municipium status, as attested by inscriptions, which conferred local self-government and integrated the settlement into the provincial administration of Alpes Cottiae. This status reflects Susa’s formal incorporation into the Roman civic framework and its role within imperial governance.

Susa’s location along the Dora Riparia and near key mountain passes endowed it with strategic significance for military logistics and regional administration. Although no direct evidence of military engagements at Susa survives, its proximity to routes used during Roman Alpine campaigns underscores its importance. Archaeological excavations reveal urban planning consistent with Roman municipal organization, including public buildings and infrastructure that indicate phases of prosperity and civic development during the 1st and 2nd centuries CE.

Late Antiquity

Following the decline of the Western Roman Empire, Susa experienced a gradual reduction in urban activity. Archaeological layers from late antiquity show diminished construction and maintenance of civic structures, reflecting broader regional instability and political fragmentation. The area was subject to incursions by groups such as the Ostrogoths and Lombards, although direct evidence of their impact on Susa is limited. No inscriptions or architectural modifications from this period have been conclusively identified, leaving the nature of occupation during late antiquity somewhat obscure.

The settlement appears to have lost its administrative prominence, with the municipium’s formal institutions likely dissolving or becoming nominal. The strategic importance of Susa waned amid shifting political landscapes, and the site’s urban fabric contracted, as indicated by archaeological evidence of partial abandonment and reduced public investment.

Medieval Period and Later

In the early medieval period, Susa’s significance diminished as political and economic centers shifted within the Piedmont region. The archaeological record for this era is sparse, with no substantial structures or inscriptions attesting to continued urban life or administrative functions. Historical sources do not document notable military or civic roles for Susa during this time. The site was gradually absorbed into emerging medieval polities, and its ancient ruins became part of the evolving landscape of the modern town.

Economic activities likely focused on subsistence agriculture and localized crafts, with no evidence of market infrastructure comparable to the Roman period. Any ecclesiastical presence at Susa during the medieval era remains undocumented archaeologically, suggesting a minor or subordinate religious role relative to larger regional centers. Overall, Susa transitioned from a municipium of regional importance to a minor settlement integrated into the medieval rural fabric.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Roman Period

Following its incorporation into the Roman Empire, Susa developed as a municipium, reflecting its integration into imperial administrative and social structures. The population comprised Roman settlers alongside indigenous Taurini and Ligurian inhabitants. Epigraphic evidence documents local magistrates such as duumviri, indicating organized municipal governance. Social stratification likely included landowning elites, artisans, and possibly enslaved individuals, consistent with Roman urban social hierarchies.

Economic activities were adapted to the Alpine environment, with archaeological finds suggesting cultivation of cereals, viticulture, and olive oil production. Amphora fragments and agricultural tools support this interpretation. Small-scale workshops and craft production likely served local needs, while Susa’s position along the Dora Riparia facilitated trade and movement through mountain passes. Urban planning and public infrastructure reflect organized civic life.

Dietary remains indicate consumption of bread, olives, fish, and locally produced wine, illustrating a Mediterranean-influenced diet adapted to regional resources. Clothing styles inferred from regional parallels include tunics and cloaks. Domestic architecture featured mosaic floors and painted walls, with houses organized around courtyards containing kitchens and storage spaces, conforming to Roman residential design.

Trade and transportation relied on animal caravans and footpaths through Alpine passes, supporting both civilian and military movement. Religious practices incorporated Roman deities, as suggested by urban structures consistent with public worship, although no specific temples have been conclusively identified. Civic ceremonies and public gatherings likely formed part of social life, though direct evidence remains limited.

Late Antiquity

During late antiquity, Susa experienced a decline in urban vitality, with reduced construction and maintenance of public buildings reflecting regional instability. The population likely decreased and became more ruralized, though occupation persisted. The ethnic composition may have diversified due to incursions by groups such as the Ostrogoths and Lombards, but direct evidence for their presence at Susa is lacking.

Economic activities shifted toward subsistence agriculture and artisanal production, with diminished long-distance trade. The absence of new monumental architecture suggests limited public investment, and household economies probably became more self-sufficient. Dietary habits likely remained similar to earlier periods but adapted to reduced market availability.

Religious life during this period is poorly documented at Susa; however, Christianity spread throughout the wider region and may have influenced local practices. No inscriptions or architectural modifications attest to ecclesiastical institutions at the site, leaving the nature of religious life uncertain. Educational and cultural activities, if present, were likely modest and localized.

Administratively, Susa’s role diminished as imperial authority waned, and municipium structures likely became nominal or dissolved. The site’s strategic importance lessened amid political fragmentation, with no evidence of military or administrative functions during this era.

Medieval Period and Later

After the late Roman period, Susa’s urban prominence faded as regional power centers shifted. The archaeological record for the early medieval era is limited, with no clear evidence of structured households or social hierarchy. The area was incorporated into emerging medieval polities, but Susa itself did not retain significant administrative or military roles.

Economic activities focused on subsistence agriculture and localized crafts, with no indications of market infrastructure or trade networks comparable to the Roman period. The settlement’s integration into the medieval landscape likely involved reuse of ancient ruins and adaptation of the terrain for agricultural purposes.

Religious life in the medieval period is not directly attested archaeologically at Susa, though the broader region saw the establishment of Christian institutions. Any ecclesiastical presence at Susa would have been minor and subordinate to larger nearby centers. Cultural and educational activities remain undocumented.

Overall, Susa transitioned from a municipium with regional significance to a minor settlement absorbed into the medieval rural fabric, its ancient urban identity largely lost amid shifting political and economic landscapes.

Remains

Architectural Features

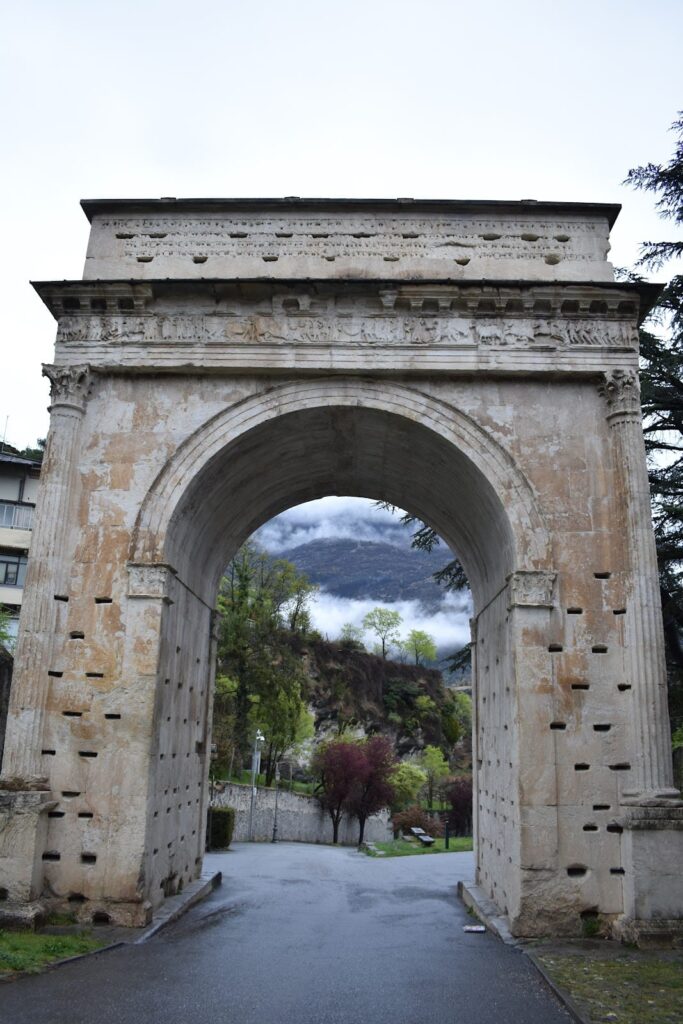

The extant archaeological remains at Susa primarily date from the late Republican through the Imperial Roman periods, approximately the 1st century BCE to the 2nd century CE. The settlement developed along the Dora Riparia river within the Susa Valley, with construction employing local stone masonry combined with Roman concrete (opus caementicium) in public edifices. The urban layout includes a combination of civic and residential structures, with evidence of planned streets and infrastructure consistent with Roman municipal organization.

Excavations indicate that the settlement expanded during the 1st century CE, reaching a phase of urban consolidation as a municipium. Subsequent layers reveal contraction of the built environment, with reduced construction activity and partial abandonment in late antiquity. Surviving ruins are fragmentary, comprising foundations, wall sections, and subsurface features documented through excavation trenches.

Key Buildings and Structures

Civic Complex

Dating to the 1st century CE, the civic complex comprises foundations of public buildings aligned along a principal street. Constructed with ashlar masonry walls, the complex includes rectangular rooms arranged around open courtyards. Archaeological evidence suggests administrative functions, including offices and meeting spaces consistent with municipium governance. Some rooms preserve plastered walls and paved floors. Limited repairs during the 3rd century CE are evident, but the complex was largely abandoned by late antiquity.

Residential Quarter

Excavations have revealed domestic structures dating from the late 1st century BCE to the 2nd century CE. These houses feature stone foundations and brick walls, often organized around small internal courtyards. Some contain hypocaust heating systems (underfloor heating) and mosaic fragments, indicating a degree of domestic comfort. After the 3rd century CE, the residential area contracted, with later occupation layers showing sporadic use and structural deterioration.

Sanitation Facilities (Public Baths)

A public bath complex constructed in the 1st century CE has been identified near the settlement’s core. The bathhouse includes rooms interpreted as caldarium (hot bath), tepidarium (warm bath), and frigidarium (cold bath), featuring vaulted ceilings and hypocaust heating systems. Walls are built of stone and brick, with some surviving floor mosaics. The baths remained in use until the late 3rd century CE, after which maintenance ceased and the structure fell into disrepair.

Infrastructure: Bridges and Roads

Archaeological surveys have documented stone bridge foundations crossing the Dora Riparia river, dating to the 1st century BCE. These bridges facilitated movement through the valley and connected Susa to transalpine routes. Excavated sections of paved Roman roads with stone curbs and drainage channels within the settlement indicate organized urban planning. Some road segments show repairs from the 2nd century CE, while later layers reveal partial abandonment.

Religious Structures

Fragmentary remains of a small temple or shrine dating to the 1st century CE have been found on the settlement’s periphery. The structure consists of a stone podium and partial wall sections, with a dedicatory altar discovered nearby. The temple’s specific deity dedication remains unconfirmed due to the absence of inscriptions or decorative elements. The building appears to have been abandoned by the late 3rd century CE.

Other Remains

Additional minor structures include storage facilities and workshop areas identified through foundation remains and concentrations of artifacts. Funerary monuments and tombs, including stone cist graves and sarcophagi fragments, have been located outside the main settlement area, dating from the late Iron Age through the Roman period. Drainage systems and cisterns constructed with stone and waterproof mortar have been documented, supporting urban sanitation.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations at Susa have yielded artifacts spanning from the Bronze Age through late antiquity. Pottery assemblages include locally produced coarse wares and imported fine tableware dating from the 2nd century BCE to the 3rd century CE. Amphora fragments indicate trade connections with Mediterranean regions. Numerous Latin inscriptions confirm municipium status and provide names of local officials and benefactors.

Coin finds encompass Republican and Imperial issues, including examples from the Julio-Claudian and Severan dynasties. Iron and bronze tools, such as agricultural implements and craft-related objects, have been recovered from domestic and workshop contexts. Domestic artifacts include ceramic lamps, cooking vessels, and glass fragments. Religious artifacts comprise small votive statuettes and altar fragments associated with the temple remains.

Preservation and Current Status

The preservation of Susa’s ruins varies considerably. Foundations and lower wall courses of major buildings remain visible, while upper structures are mostly lost. The public baths and civic complex retain partial wall sections and floor surfaces, and residential buildings survive primarily as foundation outlines. Some mosaics and hypocaust systems are preserved in situ but are fragmentary.

Restoration efforts have stabilized exposed ruins, employing modern materials to support fragile masonry without full reconstruction. Environmental factors such as river erosion and vegetation growth pose ongoing risks to unprotected areas. Urban development in the modern town has limited excavation scope and exposed some remains to damage. Conservation initiatives by local heritage authorities focus on site stabilization and protection from further deterioration.

Unexcavated Areas

Several sectors within the ancient settlement boundaries remain unexcavated or only partially investigated. Surface surveys and geophysical studies suggest buried remains of additional residential quarters and possible economic installations. The northern and eastern outskirts near the riverbanks have not undergone systematic excavation due to modern construction and preservation policies.

Future archaeological work is constrained by urban expansion and conservation regulations. Planned investigations aim to clarify the extent of late antique occupation and document subsurface features identified through remote sensing. However, large-scale excavation remains limited, preserving much of the site beneath the modern town fabric.