Palau dels Milà i Aragó: Historic Palace in Albaida, Spain

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.4

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.albaidaturisme.com

Country: Spain

Civilization: Unclassified

Remains: Military

History

The Palau dels Milà i Aragó is located in Albaida, Spain, and was originally constructed by the Christian kingdoms following the Reconquista period. Its origins lie on the site of an earlier fortified lord’s residence, likely established in the late 13th century by Admiral Conrad Llança after he acquired local baronies in 1279 and 1286. This initial structure served as a defensive stronghold during a time of territorial consolidation in the Valencian region.

Throughout the 14th and 15th centuries, the lordship of Albaida was held by the Vilaragut family until 1471. Financial difficulties resulted in the Crown auctioning the property, at which point Cardinal Lluís Joan del Milà purchased it. Cardinal Lluís Joan, a notable relative of two popes—Callixtus III and Alexander VI—initiated the establishment of Milà family ownership. Just a few years later, in 1477, the Milà family allied with the Aragó family through the marriage of Jaume del Milà and Elionor d’Aragó, niece to King Ferdinand II of Aragon. This union granted the family the title of count and, from 1604 onward, the rank of marquises of Albaida.

Initially conceived as a fortified building with an L-shaped layout and a substantial western tower, the palace underwent significant transformation between 1525 and 1550. During this Renaissance period, two additional towers were added, and the building’s orientation shifted to face the town’s main square, reflecting a move away from its purely defensive function toward a more residential and representative role. This change included the loss of much of its military character.

Later modifications in the late 16th and early 17th centuries included the construction of the archpriestal church of Santa Maria between 1592 and 1624, which occupied part of the palace’s original footprint. To accommodate the church, one wing of the palace was demolished, and a new wing constructed around 1610, opening the palace’s façade directly to the square and separating the sacred from the civic spaces of the town.

In the late 18th century, specifically between 1767 and 1768, the palace was altered to improve access to the church. A large double arch was created between the western and middle towers, allowing easier entry to the church’s side door from the palace. Beneath this arch, a small chapel was installed, housing an image of Mare de Déu del Remei, the patron saint of Albaida.

The Milà i Aragó family retained control of the palace well into the modern era. However, the main family line ended in 1841, causing the title and ownership to pass to the Orense family, who occupied the palace until the end of the 19th century. In 1896, the residence changed hands once more, this time to a local landowner and wax manufacturer. He introduced a new palace entrance from the main square between the middle and east towers. By 1912, sections of the palace had begun to be repurposed for commercial and residential uses, including rental housing, an inn, and a casino.

Beginning in 1918, the building became home to La Dominical, a Catholic bourgeois association focused on educating workers’ daughters. Ownership finally transferred to this group after the proprietor entered religious life, although preceding this donation the family had removed movable goods and the palace archive was destroyed by a local paper factory.

During the tumultuous years of the Spanish Civil War (1938–1939), the palace was requisitioned as the Center for Recruitment and Militias of Valencia and later used briefly as a regional prison. After the war, La Dominical resumed its educational and spiritual activities within the palace walls.

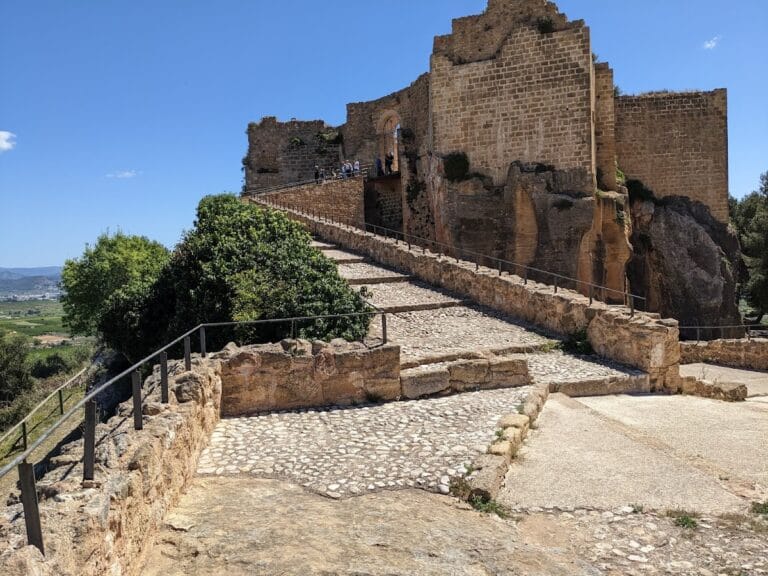

A major setback occurred on the night of December 26, 1986, when a fire badly damaged the oldest west wing. Due to insufficient emergency funds, the weakened section collapsed in November 1987, leaving only portions of the exterior walls intact. Since 1994, restoration efforts have been underway, focusing particularly on consolidating the surviving west tower.

Remains

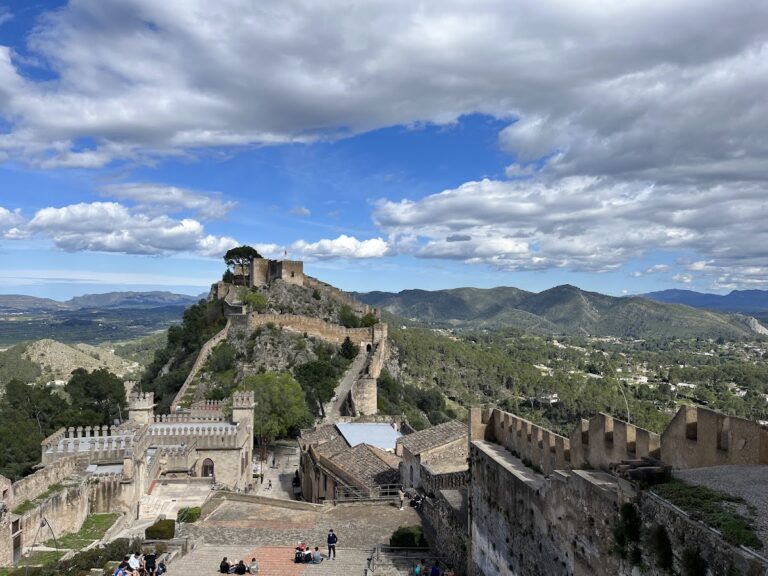

The Palau dels Milà i Aragó presents as a long, rectangular structure approximately 77 meters in length, with widths varying between roughly 6 and 19 meters. It rises to four floors but appears as a three-story building when viewed from the main square, a result of its positioning and terrain. Its original core from the late 15th century is centered around a large west tower located near what was once the main entrance of the walled enclosure surrounding the property.

The palace’s most prominent external feature is its main façade facing the Major Square. This was originally the building’s side facade; the original main façade looked inward toward a now mostly lost internal parade ground. A small square known as Vileta and the side entrance to the adjacent church of Santa Maria remain as remnants of this earlier layout. Along the main façade are three cubic towers aligned in a row, known respectively as west (Ponent), middle (Mig), and east (Llevant) towers.

Connecting the west and middle towers is a large semicircular arch dating from the 18th century. This arch is made from dressed stone blocks called ashlars, combined with brick, and was vaulted and plastered in later refurbishments. It provides access to the church and the medieval section of the town. Another archway, constructed in the late 19th century between the middle and east towers, became a new entrance after the palace passed from the marquises’ ownership. This modern access leads directly into the palace’s vestibule.

The exterior features numerous windows and balconies added over various periods, illuminating the interior and highlighting the irregular building heights. Above, a gallery of Roman-style round arches crowns the façade. Part of this gallery, specifically a Renaissance section between the middle and east towers, was demolished in 1997 but has since been rebuilt.

Construction materials reflect a combination of simple, traditional techniques—primarily rammed earth (known locally as taipa) and masonry. Later additions introduced ashlar stone and brickwork. The palace’s design blends rustic qualities with elements from Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque architectural styles.

The palace maintains a physical connection to the adjacent church of Santa Maria through a door on the noble floor. This door leads to a private gallery that overlooks the church’s presbytery and was designed to provide the marquis direct access to the church interior, a feature indicative of Baroque-era religious customs within noble households.

Three notable carved stone coats of arms decorate the palace exterior. The oldest, dating to the 16th century, is located beneath the balcony of the west tower and bears the Milà family arms. Another shield from the 17th century appears under a sundial and combines symbols representing the Milà line, the Aragó-Navarra heritage, Castile and León, and the Order of Montesa. A third complex coat of arms is situated in the former parade ground area and features numerous heraldic symbols with possible influence from English heraldry. An additional Milà coat of arms belonging to the 17th-century figure Cristòfol II is found on the church’s side door.

Inside, the palace’s original interior decoration has been heavily altered but retains an 18th-century scheme organized to separate rooms by seasonal function. Winter rooms are positioned on the upper floors, characterized by thick walls and smaller windows to conserve heat. Summer rooms occupy the mezzanine level, painted in lighter shades to convey an airy atmosphere. The tower and east wing rooms display distinct color palettes: reds and ochres dominate the summer quarters, while blues, greens, and indigos are used in the winter rooms.

The interior paintings, executed in the 1690s by Bertomeu Albert, decorate several rooms with a Baroque-themed cycle. This artwork incorporates stylized vegetal motifs alongside figures of angels, demons, various animals, mythical creatures such as centaurs, humans, and heraldic emblems. This elaborate cycle enriches the palace’s historic and artistic character.

Among the most important interior spaces are the summer hall, the tower room, a large summer room, the entrance hall, and the coat of arms room. On the noble floor, visitors would find the music room, the throne room—the palace’s most striking space—the white room, the marquis’s bedroom, and a dressing room, all reflecting the building’s layered history and social significance.