Miranda Castle: A Medieval Fortress in Zaragoza, Spain

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.1

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Country: Spain

Civilization: Unclassified

Remains: Military

History

Miranda Castle is a medieval fortress situated near Juslibol in Zaragoza, Spain. Its origins and development are closely connected to the various civilizations that have occupied the site from ancient times through the late Middle Ages.

Archaeological findings reveal that the location of Miranda Castle was continuously inhabited from at least the Iron Age. Initially, it hosted an urban settlement of Iberian communities before becoming part of the Roman world. During the Roman period, which lasted until around the reign of Emperor Caesar Augustus, the site was linked to the civitas Salluiensis, the ancient city of Salduie belonging to the Sedetani tribe. Among the Roman remains discovered are fine terra sigillata pottery and a basilical building with three naves separated by rows of pillars, indicating the presence of notable public or religious structures. As the nearby city of Caesaraugusta (modern Zaragoza) grew in prominence, the Roman settlement here was eventually abandoned.

In the subsequent Andalusian period, the site saw renewed occupation and construction, including the beginnings of the castle on the eastern side of the hill. The old Roman basilica was likely converted into a rural mosque, maintaining its three-nave layout and featuring a mihrab, a niche indicating the direction of Mecca. This change points to the site’s integration within the 10th-century Islamic city camp of al-Ŷazīra, established by Abd al-Rahman III between 935 and 937.

The castle entered Christian hands in 1101 when forces led by King Pedro I seized it, assigning it the name “Miranda,” a term commonly used in northern Christian regions to label places with commanding views. During the 1118 siege of Zaragoza by the Aragonese kingdom, Miranda played an important strategic role, assisting in the conquest of the city over the Almoravid dynasty.

Following Zaragoza’s incorporation into the Kingdom of Aragon, the castle and its surrounding settlement were given to the noble Garcés family in 1134. Control shifted to the Zaragoza bishopric in 1160, marking the beginning of ecclesiastical influence over the site. The castle reached its height during the 13th century under King James I, who in 1235 granted it the Fuero of Zaragoza, a legal charter, and formally integrated the fortress into the royal domain by 1258. Around this period, a nobleman named Jimeno de Foces likely carried out renovations that refined the castle’s appearance, emphasizing its status as a lordly residence.

Ownership changed once more in 1323 when King James II sold Miranda to the archbishopric of Zaragoza. After that date, records about the castle decline, suggesting it was gradually abandoned before the end of the 15th century, possibly due to population losses linked to the epidemics that affected the region in the 14th century.

At some point after its decline as a fortress, the castle’s main tower was converted into a hermitage dedicated to the Virgin of Miranda. The tower was altered to include a small bell structure, known as a bell gable, which housed a bell until it was stolen in the 1960s. This chapel remained active until the mid-19th century.

From the 1970s onward, the area including Miranda Castle was incorporated into the San Gregorio military training zone, which has contributed to damage of the ruins through military activities, vandalism, and archaeological excavations. Recognizing its cultural importance, Aragonese authorities declared the site a Bien de Interés Cultural in 2006, marking it as a protected heritage site.

Remains

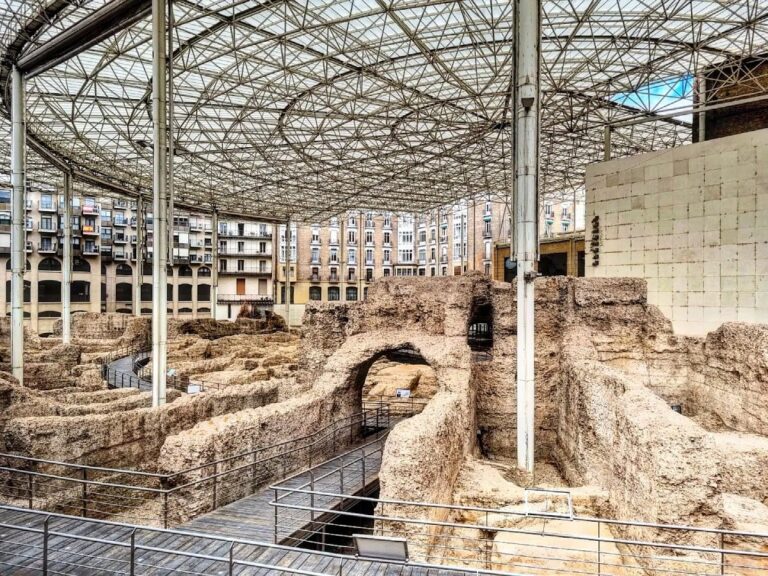

The castle occupies a rocky hill with an irregular outline adapted to the natural landscape. Defensive measures included a deep and wide artificial moat on the northwest side, measuring roughly 15 meters across and more than 10 meters deep in places, aimed at enhancing the site’s security. On the southwest, significant modifications to the terrain created a steep base for the walls, increasing their height, though this section has suffered considerable deterioration.

Access to the castle was controlled through a path on the northeast side, guarded by a large rectangular albarrana tower—an isolated defensive tower connected to the main castle walls by a walkway. This tower was constructed using gypsum mortar mixed with irregular gypsum stones, later reinforced at the base with bricks. Over time, it has become heavily tilted and faces the risk of collapse. The main gate, positioned at the northern corner before the moat, has undergone extensive alterations. It led to a winding ramp that ascended behind the albarrana tower, flanked by the lower curtain wall of the castle. Today, only the sloping base of this wall, known as the alambor, and some ruined structures remain on the western flank.

The upper enclosure of the castle is divided into two functional levels. The lower level includes a rectangular tower reinforced with pilasters and four distinctive horseshoe arches facing north, a feature hinting at Islamic influence typical of medieval Iberian architecture. Adjacent to this lower tower is the main keep, separated by a narrow corridor that provides access to the castle’s upper level. Within the lower section of the main tower are the remains of what once served as the entrance and a religious niche, vestiges from its later adaptation as a hermitage devoted to the Virgin of Miranda.

Above, the upper level contains a filled-in cistern (known in Spanish as an aljibe) once used for water storage, as well as a terrace offering commanding views of the Ebro plain and the city of Zaragoza beyond. Surrounding the upper bailey, or courtyard, the defensive courtyard wall survives only as gypsum masonry foundations, accompanied by traces of external buttresses on some sides that once supported the structure.

The main tower itself has lost about half of its original rectangular perimeter. Internally, it consisted of two floors separated by a brick barrel vault, part of which remains intact. The second floor featured a large pointed arch on its east side, which functioned as the bell gable for the hermitage, but the original bell was removed in the 1960s. Access to this upper chamber was through a door in the southwest wall, characterized by a slightly pointed arch made of finely carved alabaster voussoirs—the wedge-shaped stones typical of traditional arch construction.

The tower’s upper structure displays significant alterations, including twin gable ends on its short sides built to support a pitched roof. Remnants of roof tiles lie scattered around the base. The method of construction involved use of formwork panels approximately 0.80 by 1.20 meters in size, notable for lacking holes or slots needed to insert formwork clamps, a detail suggesting a building technique from the late medieval period.

Near the base of the albarrana tower on the hillside, there is a passageway that opens into a large underground chamber. Until the 1960s, this gallery was accessible and included a descending corridor leading to an exit near the river, which still exists today.

Together, these surviving elements illustrate Miranda Castle’s long and varied history—from its Iron Age and Roman beginnings, through Islamic and Christian medieval transformations, to its eventual religious re-use and modern preservation challenges.