Itálica: An Ancient Roman City in Andalusia, Spain

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.6

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.museosdeandalucia.es

Country: Spain

Civilization: Roman

Remains: City

Context

Itálica is situated immediately north of the modern town of Santiponce, within the province of Seville in Andalusia, Spain. The archaeological site occupies a gentle elevation on the alluvial plain of the Guadalquivir River, approximately nine kilometres northwest of present-day Seville. This location overlooks former river channels of the Baetis, the Roman name for the Guadalquivir, providing strategic oversight of the fertile river valley.

Founded in the early 3rd century BCE, Itálica developed as a Roman settlement positioned to control riverine routes and regional communication between indigenous cities such as Hispalis (modern Seville) and Ilipa. The site’s landscape includes low hills and proximity to natural springs, which supported its water supply systems. Archaeological stratigraphy reveals continuous occupation from its foundation through the Roman Imperial period into Late Antiquity and the early medieval era, with evidence of gradual urban contraction over time.

Since the nineteenth century, systematic archaeological investigations have uncovered extensive urban layouts, including street grids, public buildings, and richly decorated private residences. Numerous mosaics, inscriptions, and architectural elements have been conserved, contributing to the understanding of Roman urbanism in Hispania. Today, Itálica is managed by Andalusian heritage authorities and serves as a significant locus for archaeological research and cultural heritage preservation.

History

Itálica’s historical trajectory spans over a millennium, reflecting the complex political, social, and cultural transformations of Roman Hispania and subsequent periods. Established as a Roman military colony, the city evolved into a prominent urban centre during the early Imperial era, notably as the birthplace of emperors Trajan and Hadrian. Its development mirrored broader provincial dynamics, including Roman administrative reforms, Visigothic governance, and later Islamic rule, before its eventual decline and abandonment in the medieval period.

Foundation and Republican Period (3rd–1st century BCE)

Itálica was founded in 206 BCE by the Roman general Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus during the Second Punic War. The settlement was established primarily to accommodate wounded and retired Roman soldiers, many of Italic origin, on the site of a preexisting Turdetani indigenous community dating back to at least the 4th century BCE. Its strategic position near the Guadalquivir River, between the native cities of Hispalis and Ilipa, allowed control over river traffic and facilitated military and economic oversight of the region.

The original urban plan, known as the vetus urbs (“old city”), was laid out according to a Hippodamian grid system characteristic of Roman military colonies. Initially, Itálica likely held the status of a Latin colony, which conferred limited Roman citizenship rights. By approximately 45 BCE, Julius Caesar elevated the city to municipium civium Romanorum, granting full Roman citizenship as a reward for its allegiance during the civil wars. The population comprised Roman veterans, their descendants, and local women, with prominent families such as the Ulpii and Aelii, ancestors of emperors Trajan and Hadrian respectively. Numismatic evidence from the Augustan period includes bronze coins bearing imperial effigies, underscoring the city’s integration into Roman political and cultural frameworks.

Imperial Roman Period (1st–3rd century CE)

Itálica attained its zenith during the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, particularly under the reigns of emperors Trajan and Hadrian, both natives of the city. Hadrian initiated a significant urban expansion northward, establishing the nova urbs (“new city”) with a formal Hippodamian street grid and monumental public architecture. The city was elevated to colonia status as Colonia Aelia Augusta Italica, a prestigious designation that aligned it symbolically and administratively with Rome itself, often described as a “simulacrum Romae.”

Key constructions from this period include a vast amphitheatre with an estimated capacity of 25,000 spectators, ranking as the fourth largest in the Roman Empire. Public amenities such as the Thermae Maiora (large public baths) occupied entire city blocks and featured complex facilities including heated rooms, exercise areas, libraries, and saunas. Defensive walls, constructed and expanded from the late Republic through Hadrian’s reign, enclosed over 50 hectares with a perimeter exceeding 3,000 meters. The elite residential quarter contained luxurious domus adorned with intricate mosaics and architectural innovations, exemplified by the House of the Exedra and the House of the Planetarium. The city’s aqueduct system, initially built in the early 1st century CE, was extended under Hadrian to source water from distant springs, incorporating brick-lined channels and large cisterns. These developments reflect Itálica’s elevated status and integration within the imperial urban network.

Late Antiquity and Visigothic Period (4th–7th century CE)

During Late Antiquity, Itálica experienced demographic contraction and urban reorganization, with abandonment of the Hadrianic nova urbs and continued occupation of the older vetus urbs. The city retained ecclesiastical significance as a bishopric, with documented bishops attending church councils until the late 7th century, including Bishop Cuniuldo at the 16th Council of Toledo in 693 CE. The Visigothic king Leovigildo restored the city’s defensive walls in 583 CE amid internal conflicts, indicating ongoing military and administrative relevance.

Economic decline was exacerbated by the silting and shifting of the Guadalquivir River, which rendered the city’s port unusable and diminished its commercial role. The urban fabric contracted, and the city’s prominence waned as nearby Hispalis (Seville) ascended in regional importance. Archaeological evidence suggests continued, albeit reduced, use of public and domestic structures, with a shift toward Christian religious practices supplanting earlier pagan cults. Transport increasingly relied on overland routes as river navigation declined.

Islamic Period and Final Abandonment (8th–12th century CE)

Following the Islamic conquest of the Iberian Peninsula in the early 8th century, Itálica became known as Talikah or Taliqa in Arabic sources. By the 10th century, the site was largely depopulated, with limited occupation focused on subsistence agriculture and pastoralism. Archaeological remains from this period are sparse, though individuals bearing the nisba al-Talikí are recorded, indicating some residual recognition of the site’s identity.

The city’s infrastructure deteriorated, and no significant Islamic religious or civic buildings have been conclusively identified. The strategic and economic importance of Itálica vanished, supplanted by the growing urban centre of Seville. By the 12th century, the site was fully abandoned and referred to by Christians as Campos de Talica or Sevilla la Vieja. The urban landscape transitioned into a ruinous state, marking the end of Itálica’s habitation.

Modern Rediscovery and Archaeological Investigations (16th century–present)

Itálica’s historical significance as the birthplace of emperors Trajan and Hadrian was recognized from at least the 16th century. From the 18th century onward, travelers and scholars documented the ruins, although the site suffered damage from quarrying and construction projects, including the partial demolition of the amphitheatre and city walls. The first legal protections were introduced during the Napoleonic occupation in 1810, with systematic archaeological excavations commencing in the 1830s.

Excavations intensified in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with significant mosaics and artifacts acquired by private collectors and museums. The site was declared a National Monument in 1912, but comprehensive protective measures and clear delimitation of the archaeological zone were only established in 2001 by regional heritage authorities. Recent decades have seen extensive archaeological work uncovering urban layouts, public buildings, and elite residences, alongside conservation efforts. The amphitheatre and theatre have been restored and adapted for cultural events, while the aqueduct remains are integrated into protected natural corridors, underscoring ongoing commitments to heritage preservation and research.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Foundation and Republican Period (3rd–1st century BCE)

During its foundation, Itálica functioned primarily as a settlement for Roman veterans, predominantly of Italic origin, who were granted land in the fertile Guadalquivir valley. The population was a mixture of Roman citizens, their descendants, and local Turdetani women, forming a socially stratified community that included veteran landowners, artisans, and enslaved individuals. Epigraphic evidence attests to municipal magistracies such as duumviri, indicating the presence of Roman-style local governance.

Economic activities centered on agriculture, exploiting the rich alluvial soils to produce staples such as cereals, olives, and grapes. Household-scale production of olive oil and wine likely supported both local consumption and regional trade. The nearby river port facilitated transport and commerce along the Guadalquivir. Domestic architecture conformed to Roman models, with atria and peristyles, although early structural remains are limited. Diet included cereals, olives, fish from the river, and livestock products. Religious practices combined Roman state cults with indigenous traditions, though early temples remain archaeologically elusive.

Imperial Roman Period (1st–3rd century CE)

In the Imperial era, Itálica’s population expanded and diversified, reaching its height under emperors Trajan and Hadrian. The social hierarchy became more complex, with a wealthy elite residing in expansive domus such as the House of the Exedra and House of the Planetarium, alongside artisans, merchants, and slaves. Inscriptions document civic magistrates and religious officials administering the colonia Aelia Augusta Italica, which emulated Rome’s urban and administrative structures.

Economic life flourished with large-scale public works and urban amenities. Agriculture remained foundational, supplemented by artisanal production of mosaics, pottery, and textiles. The city’s port enabled trade connections across the Mediterranean. The aqueduct system ensured reliable water supply for public baths, fountains, and private households. Markets and tabernae within residential blocks facilitated commerce, offering imported luxury goods alongside local products. Daily life reflected Roman urban customs, with diets including bread, olives, fish, and imported delicacies; clothing ranged from tunics to togas for elites. Public baths served as centers for hygiene, socializing, and intellectual pursuits. Religious life included imperial cult worship in temples such as the Traianeum, and public spectacles in the amphitheatre fostered civic identity.

Late Antiquity and Visigothic Period (4th–7th century CE)

Following the contraction of the urban area, Itálica’s population remained predominantly Romanized Hispano-Roman under Visigothic political control. Bishops such as Cuniuldo, recorded at the 16th Council of Toledo, indicate an active Christian community and ecclesiastical hierarchy. Social stratification persisted, though urban opulence diminished.

Economic activities shifted toward local subsistence, with reduced long-distance trade due to the silting of the river port. Agriculture and small-scale artisanal production likely predominated. Archaeological evidence suggests continued, though simplified, use of public buildings and domestic spaces. Religious practices centered on Christianity, with churches replacing pagan temples. The Visigothic restoration of city walls by King Leovigildo highlights ongoing military and administrative functions. Transport increasingly relied on overland routes as river navigation declined. The city transitioned from a flourishing Roman colonia to a diminished episcopal center within the Visigothic kingdom.

Islamic Period and Final Abandonment (8th–12th century CE)

Under Islamic rule, Itálica—known as Talikah or Taliqa—experienced significant depopulation and urban decay. The remaining population was sparse, with archaeological evidence indicating limited occupation focused on subsistence agriculture and pastoralism. Social structures were minimal, with few permanent residents. Economic activity was largely subsistence-based, with no evidence of significant trade or manufacturing. The port was unusable, and infrastructure deteriorated. Domestic architecture was rudimentary, and public buildings were abandoned or sporadically repurposed. Religious life shifted to Islam, though no major Islamic religious structures have been conclusively identified on site. The city’s strategic and civic importance vanished, supplanted by Seville. By the 12th century, Itálica was fully abandoned, its ruins known to Christians as Campos de Talica or Sevilla la Vieja.

Modern Rediscovery and Archaeological Investigations (16th century–present)

Modern archaeological investigations have illuminated Itálica’s urban development, social stratification, and cultural practices across its history. Systematic excavations have revealed street plans, elite residences, public baths, and the amphitheatre, providing detailed insights into daily life and civic organization. Conservation of mosaics and architectural elements has enhanced understanding of domestic decoration and urban amenities. The site’s recognition as the birthplace of emperors Trajan and Hadrian has underscored its historical prestige. Ongoing research continues to refine knowledge of Itálica’s evolution from a Roman military colony to an imperial city and its subsequent decline.

Remains

Architectural Features

Itálica’s urban fabric reflects its origin as a Roman military colony with a Hippodamian grid plan established in the late 3rd century BCE. The city expanded notably during the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, particularly under Hadrian, who developed the nova urbs district. The city walls, constructed in multiple phases from the late Republic through the 2nd century CE, enclosed over 50 hectares at their greatest extent. These walls, averaging 1.5 meters in thickness, incorporated Roman concrete cores faced with ashlar masonry and included towers and gates. They served both defensive and symbolic functions, marking the city’s sacred boundary, and were restored in the late 6th century CE by Visigothic king Leovigildo.

Two aqueducts supplied Itálica with water. The older aqueduct, dating to the early 1st century CE, primarily served the vetus urbs and featured massive concrete construction with circular inspection shafts. The Hadrianic aqueduct, built in the early 2nd century CE, was fully brick-lined—a rare feature in the Roman Empire—and included elevated arcades to maintain a steady gradient. It supplied the nova urbs and fed large cisterns near the amphitheatre. A well-preserved section of this aqueduct crosses the Guadiamar River.

Residential and public buildings exhibit diverse construction techniques, including Roman concrete, brick, and ashlar masonry. Many houses feature porticoed peristyles, vaulted rooms, and hypocaust heating systems. The city contracted gradually from Late Antiquity onward, with abandonment of the Hadrianic district and reduction of the urban area, especially after the Guadalquivir River’s silting diminished port access.

Key Buildings and Structures

City Walls

The city walls were constructed in several phases from the late Republic through the 2nd century CE. At their maximum extent, they enclosed over 50 hectares with a perimeter exceeding 3,000 meters. The walls averaged 1.5 meters thick and consisted of concrete cores faced with ashlar masonry. Surviving remains include an Augustan-era tower near the theatre, built with concrete and vertical bands of ashlar, and foundations of a Hadrianic phase near the amphitheatre. The walls were restored in 583 CE by Visigothic king Leovigildo during his conflict with Hermenegild. A geophysical survey in the early 1990s identified a late Roman or Visigothic wall section behind the Traianeum.

Amphitheatre

Constructed in the early 2nd century CE, the amphitheatre is among the largest in the Roman Empire, with an estimated seating capacity of approximately 25,000. It features three tiers of elliptical seating surrounding the arena. Beneath the former wooden arena floor lies a service pit (fossa) used for staging gladiatorial combats and wild beast shows. The amphitheatre was partially demolished in 1740 by order of the Seville city council to facilitate dam construction on the Guadalquivir River. Surviving remains include sections of seating and the arena perimeter.

Theatre

The theatre, built between the late 1st century BCE and early 1st century CE, is the oldest known civil building in Itálica after probable curia remains found nearby. Located on San Antonio hill west of Santiponce, it was used sporadically until at least the 5th century CE. After abandonment, parts of the theatre were filled with earth and repurposed for storage, animal enclosures, and occasional medieval burials. Flooding from the Guadalquivir eventually buried the structure. Excavations in the 1970s uncovered the seating area and stage foundations, with restoration work beginning in the 1980s. The semicircular seating (cavea) and orchestra area remain partially preserved. The theatre is currently used for cultural events such as the Itálica Theatre Festival.

Traianeum

The Traianeum is a large temple complex constructed in the early 2nd century CE, presumed dedicated to Emperor Trajan. Built by Hadrian, the temple occupies a central double insula at the highest point of the nova urbs. The precinct measures approximately 108 by 80 meters and is surrounded by a porticoed square featuring alternating rectangular and semicircular exedrae that housed sculptures. The temple was decorated with over 100 columns of Cipollino marble imported from Euboea and included various fountains. Foundations and column bases remain visible, outlining the temple’s monumental scale.

Large Public Baths (Thermae Maiora or Baths of the Queen Mora)

Dating to the Hadrianic period in the early 2nd century CE, the large public baths occupy an entire city block of about 32,000 square meters in the nova urbs. The complex includes typical bathing rooms such as the caldarium (hot bath), tepidarium (warm bath), frigidarium (cold bath), and laconicum (sweat room), as well as possible exercise yards (palaestrae). The baths feature a grand staircase leading to a vestibule and a T-shaped pool with white marble walls and floors. Surrounding rooms include service areas, a library, massage room, sauna, and changing rooms. A large rectangular palestra extends nearly the full length of the building, ending in a vaulted exedra. The structure is partly unexcavated and has suffered looting, but substantial remains survive.

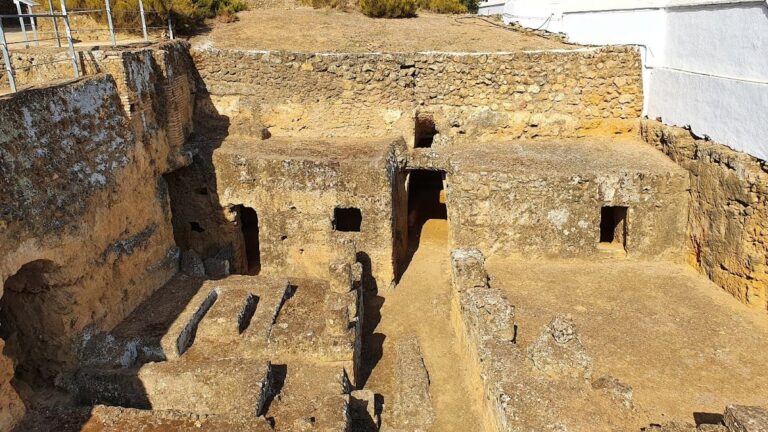

Small Public Baths (Thermae Minor or Baths of Trajan)

Located within the old city (vetus urbs) beneath modern Santiponce, these smaller baths date to the Trajanic period (98–117 CE) with structural reinforcements from Hadrian’s reign. Covering approximately 1,500 square meters, the excavated portions include two hot rooms (caldaria), a warm room (tepidarium), a cold room (frigidarium), and exercise areas. The full extent of the baths extends beneath surrounding modern houses, especially near the main entrance. The baths were constructed using typical Roman techniques, including hypocaust heating systems.

Aqueducts

Itálica was supplied by two main aqueducts. The older aqueduct, dating from the early 1st century CE, brought water from springs near the Guadiamar River to the vetus urbs. Much of this aqueduct runs underground, with visible remains including a 40-meter-long vaulted gallery at La Pizana (Gerena). It was constructed with massive concrete and featured circular inspection shafts (lumbreras). The Hadrianic aqueduct, built in the early 2nd century CE, extended the water supply from more distant springs near Peñalosa de Tejada la Nueva. This aqueduct was fully brick-lined, a rare feature in the Roman Empire, and included elevated arcades to maintain gradient. Some piers remain, notably a well-preserved section crossing the Guadiamar River. Both aqueducts fed large three-nave cisterns near the amphitheatre, discovered in the 1970s.

House of the Exedra

This large building occupies an entire insula of about 4,000 square meters and dates to the 2nd century CE. Its function is uncertain but may have been a domus or semi-public building with residential quarters. The entrance is flanked by seven tabernae (shops) on the sides and additional shops on the right and rear. The interior includes a vestibulum leading to a rectangular peristyle with a central elongated curved pool or fountain. The peristyle is supported by large cruciform pillars connected by arches, likely to bear heavy loads and possibly support upper floors. Numerous bedrooms (cubicula) surround the peristyle, with one opening to the exterior. Stairs at the rear lead to a bath complex arranged around an interior courtyard, including two bath chambers with quarter-sphere vaulted ceilings. A large rectangular palestra nearly the full length of the building ends in a vaulted exedra and connects to the exterior via a corridor. The building is divided into four zones: tabernae, baths, domus, and exedra with palestra. It features an opus sectile geometric mosaic with fifteen framed panels displaying circular and star-shaped astral motifs.

House of Neptune

Occupying an entire insula of approximately 6,000 square meters, this semi-public building dates to the 2nd century CE and is only partially excavated. The western sector includes a well-preserved bath complex with a tepidarium, caldarium with brick hypocaust pillars, and a frigidarium decorated with the Neptune mosaic. This mosaic depicts the god Neptune with a trident driving a chariot pulled by hippocamps, surrounded by marine creatures and mythological figures, mostly in black and white except for Neptune in polychrome. Other mosaics include a walled city with a labyrinth and Bacchic scenes featuring dancing maenads, satyrs, centaurs, and tigers. A large cistern is located in the northern part of the building. The structure likely served functions similar to the House of the Exedra.

House of the Rhodian Patio

Partially excavated and oriented east, this residential building dates to the 2nd century CE. It is characterized by several consecutive open spaces arranged around which rooms are distributed. The main feature is a Rhodian-style patio with one gallery higher than the others and steps to manage level changes. Floors were decorated with high-quality mosaics, many now lost or deteriorated. The house includes a series of basins associated with a small pool, possibly used as a laundry area. The entrance location is debated, possibly from the east via a large vestibule or less likely from the south facade. The main peristyle had a square fountain and one gallery higher than the rest. It connects to two triclinia, one decorated with mosaics allegorizing the four seasons and the other larger with tiger mosaics, flanked by two patios. Additional mosaic-floored rooms are accessed from these patios.

House of Hylas

This luxurious house, dating to the 2nd century CE, is only partially excavated and has an uncertain layout. The entrance is debated between an east vestibule or the south facade. The main peristyle features a square fountain and a Rhodian patio with one gallery higher than the others. It connects to two triclinia, one decorated with a mosaic depicting the four seasons. The northern patio links via stairs to an antechamber leading to the room with the Hylas mosaic, which shows the abduction of Hylas by nymphs under the supervision of Hercules. The central mosaic panel is now housed in the Provincial Archaeological Museum of Seville, with only surrounding geometric decorations remaining in situ.

House of the Birds

This residential building follows a typical Roman domus layout with a porticoed peristyle surrounded by rooms. It likely belonged to an aristocratic family and was the first fully excavated house in the Itálica complex. The house contains numerous high-quality mosaics, including one depicting birds that gives the house its name. The structure has been restored and delineated with low walls about 60 cm high marking different rooms. The entrance leads to a vestibulum connecting to the fauces and then the peristyle with a well. A covered rectangular corridor surrounds the peristyle with doors opening to various rooms. The triclinium is located at the rear, flanked by two open patios (exedrae), one with a fountain and the other with a pool. Service areas, kitchens, and drainage systems are located in the wings. The bird mosaic is located in a cubiculum on the left side. The main facade includes tabernae (shops) associated with the house, one of which contains an oven.

House of the Planetarium

Constructed under Hadrian in the early 2nd century CE, with late Roman modifications, this residential building covers nearly 1,600 square meters excluding tabernae. It occupies the western half of an insula between the amphitheatre and the Traianeum. The house is named after a mosaic depicting the seven planetary deities representing the days of the week, with Venus at the center surrounded by the Moon, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Saturn, and the Sun. The building was intended for notable citizens, distinguished by its prime location, construction quality, luxury finishes, and large habitable area. Entry is through an ostium leading to a vestibule and tablinum (reception room) opening onto the peristyle. Around the peristyle lies a large porticoed garden with columns, bedrooms (cubicula), and reception rooms (oeci). The two westernmost areas include lateral rooms and bedrooms opening onto a larger rear room with access to the atrium, a square space with an opening in the roof for air, light, and rainwater. The triclinium is located at the rear of the peristyle, aligned with the main axis and flanked by additional rooms and patios. Late Roman modifications divided the peristyle into two parts: the northern part remained domestic with mosaics, while the southern part became a garden or patio. Columns in the southern part were replaced by large pillars supporting a second floor. Late structures related to service areas were superimposed on 2nd-century rooms at the rear of the peristyle.

Other Remains

Probable remains of a curia (council chamber) were discovered near the theatre in 1984. Surface traces of walls and foundations are scattered across the site, indicating additional unexcavated or partially excavated structures, especially in the nova urbs. The old city (vetus urbs) lies beneath the modern town of Santiponce, with few visible Roman remains apart from the theatre and small public baths. Some buildings and structures remain unexcavated or only partially studied, particularly in the expanded Hadrianic district.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations at Itálica have uncovered numerous mosaics, inscriptions, coins, and domestic objects spanning from the city’s foundation in the late 3rd century BCE through Late Antiquity. Mosaics include geometric opus sectile panels, mythological scenes such as the Neptune mosaic, and allegories of the four seasons. Inscriptions record dedications and civic honors, including references to the Ulpii and Aelii families. Coins minted during the Augustan period and later Imperial times have been found, confirming the city’s Roman identity and economic activity. Domestic objects such as lamps, cooking vessels, and furniture fragments have been recovered from residential quarters. Religious artifacts include statuettes and altars associated with the Traianeum and other sanctuaries. Many finds were locally produced, while some materials, such as Cipollino marble columns, were imported from the eastern Mediterranean.

Preservation and Current Status

The ruins of Itálica vary in preservation. The amphitheatre and theatre retain substantial structural remains, though the amphitheatre was partially demolished in the 18th century. The Traianeum temple foundations and porticoed square remain visible but incomplete. Large public baths survive in fragmentary condition, with some areas unexcavated and others heavily looted. Residential houses such as the House of the Exedra, House of Neptune, and House of the Birds preserve mosaics and architectural elements, though some are only partially excavated. The city walls survive in sections, including towers and foundations. Aqueduct remains include underground galleries and standing piers. Restoration efforts have stabilized and partially restored the theatre and amphitheatre, while mosaics and architectural fragments have received conservation treatment. The site is managed by Andalusian heritage authorities, with ongoing archaeological research and conservation programs.

Unexcavated Areas

Significant portions of the nova urbs remain unexcavated or only partially studied, including residential insulae and public buildings. Surface surveys and geophysical studies conducted in the 1990s identified previously unknown wall sections and buried structures, suggesting further archaeological potential. The old city beneath modern Santiponce is largely inaccessible due to overlying urban development, limiting excavation possibilities. Conservation policies prioritize preservation of exposed remains, and future excavations are planned selectively to balance research with site protection.