Concordia Sagittaria: A Roman Colony and Early Christian Center in Northeastern Italy

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.5

Popularity: Very Low

Country: Italy

Civilization: Byzantine, Roman, Venetian

Site type: Burial, City, Civic, Domestic, Economic, Entertainment, Infrastructure, Military, Religious, Sanitation

Context

Concordia Sagittaria is situated in the Veneto region of northeastern Italy, near the modern municipality bearing the same name within the province of Venice. The site occupies a flat alluvial plain shaped by the Piave River system, lying close to the Adriatic Sea coast. This low-lying landscape, intersected by multiple waterways including the Lemene and Reghena rivers, provided strategic access to both inland and maritime routes, facilitating communication and trade throughout antiquity.

The surrounding fertile soils supported sustained agricultural production, which underpinned the settlement’s economy from its foundation. Established as a Roman colony in the late 1st century BCE, Concordia Sagittaria benefited from its position at the junction of major Roman roads and proximity to navigable rivers. The site remained occupied through the Roman Imperial period and into the early medieval era, although environmental factors such as river course changes and recurrent flooding gradually diminished its urban vitality, as demonstrated by stratigraphic and geomorphological studies.

Archaeological investigations, initiated in the 19th century and continuing intermittently, have revealed well-preserved elements of Roman urban planning and early Christian architecture. The site’s preservation owes much to its burial beneath alluvial deposits, which shielded structures from extensive erosion. Contemporary conservation efforts prioritize the stabilization of exposed ruins and the protection of archaeological stratigraphy, while ongoing research seeks to refine understanding of the site’s occupational history and environmental context within the broader Veneto region.

History

Concordia Sagittaria’s historical significance derives from its role as a Roman colonial foundation and later as an ecclesiastical center in northeastern Italy. Founded in the late 1st century BCE, the settlement developed at the crossroads of two principal Roman roads, the Via Annia and Via Postumia, linking it to Aquileia and other key urban centers within Regio X Venetia et Histria. Over time, it transitioned from a Roman military and administrative outpost to a locus of early Christian worship and medieval religious authority. Its gradual decline in urban prominence was influenced by environmental challenges, including flooding and river course shifts, yet it retained religious importance through its bishopric and associated ecclesiastical structures. Archaeological research has progressively illuminated the site’s complex historical trajectory, revealing its multifaceted civic, military, and religious functions.

Roman Foundation and Imperial Period (1st century BCE – 3rd century CE)

Concordia Sagittaria was established circa 42 BCE as the Roman colony Iulia Concordia, strategically positioned at the intersection of the Via Annia and Via Postumia. These roads facilitated vital connections between Aquileia, the Venetian hinterland, and the broader Roman world. The colony’s location near the Lemene River and the Adriatic coast enabled both riverine and maritime communication, supporting its military and administrative roles within the imperial provincial framework of Regio X Venetia et Histria.

Archaeological evidence attests to a well-planned urban grid, featuring a Decumanus Maximus oriented east-west and a Cardo Maximus running north-south, both paved with durable trachyte stones. The city was enclosed by defensive walls and gates, including the eastern Porta Urbis near Via Faustiniana and the northern gate at the junction of Via Mazzini and Via Claudia. A Roman bridge spanning the Reghena River carried the Via Annia into the city, underscoring its infrastructural integration. Public amenities such as baths located along Via Claudia, warehouses (magazzini), private residences (domus), wells, and a theatre—whose semicircular perimeter remains traceable—reflect a developed urban environment.

Concordia hosted a specialized arrow-making industry, evidenced by archaeological finds and epigraphic references, which influenced the later adoption of the name “Sagittaria” in the 19th century. Inscriptions and funerary monuments reveal a socially diverse population comprising soldiers, centurions, public officials, artisans, slaves, and merchants. The “Sepolcreto dei militi,” a military cemetery situated on the left bank of the Lemene River, contains numerous sarcophagi dating to the 4th and 5th centuries CE, indicating the city’s sustained military presence during the late Roman period.

Late Antiquity and Early Christian Period (4th–5th centuries CE)

The 4th century CE witnessed the establishment and consolidation of Christianity in Concordia Sagittaria, exemplified by the construction of the Basilica Apostolorum beneath the present-day cathedral. Dating to approximately 389 CE, this early Christian complex includes mosaics bearing donor inscriptions and a funerary chapel containing the elaborately decorated sarcophagus of Faustiniana, a wealthy Christian patron. Adjacent ruins preserve a martyrium dedicated to local martyrs who suffered persecution under Diocletian around 304 CE.

During this period, the city endured significant upheaval, notably a destructive fire in 452 CE attributed to Attila the Hun’s invasion, which contributed to the decline of its urban infrastructure. Despite this, the Christian religious complex retained its prominence, with Concordia maintaining its status as a bishopric seat from the late 4th century onward. Episcopal residence persisted until 1586, after which the seat was successively relocated to Portogruaro and later to Pordenone in the 20th century, reflecting shifting ecclesiastical and political dynamics.

Early Medieval Period (6th–11th centuries CE)

Following the disintegration of Western Roman imperial authority, Concordia Sagittaria became incorporated into the Lombard Duchy of Cividale. Subsequently, it was integrated into the March of Friuli and the Patriarchate of Aquileia. The settlement experienced demographic contraction and urban decline, exacerbated by recurrent flooding and the systematic reuse of Roman building materials, which led to the progressive loss of much of the ancient urban fabric.

The medieval cathedral was reconstructed on the site of the earlier basilica, preserving the location’s religious significance. Adjacent to the cathedral, an 11th-century Romanesque baptistery was erected, characterized by a Greek cross plan with three apses and interior frescoes depicting Christ Pantocrator, angels, saints, and evangelists including St. Mark and St. George. The cathedral’s Romanesque bell tower dates to circa 1150, while the main cathedral structure largely reflects 15th-century construction with subsequent 19th and 20th-century modifications. The complex houses relics of local martyrs and artworks spanning several centuries, illustrating continuity in religious practice and artistic traditions.

Venetian and Modern Period (15th century – 20th century)

In 1420, Concordia Sagittaria and the wider Friuli region were annexed by the Republic of Venice, integrating the town into Venetian political and economic systems. Administrative reorganization in 1838 transferred the town from the Patria del Friuli to the province of Venice. The official renaming to Concordia Sagittaria in 1868 underscored its Roman origins and historical association with arrow production.

The Palazzo Comunale, constructed in 1523 with funding from Bishop Giovanni Argentino, overlooks the Lemene River and contains a modest archaeological collection. In the early 20th century, a white marble statue by Cardinal Celso Costantini commemorated local efforts to reclaim marshy lands, reflecting ongoing agricultural development. The cathedral was declared a national monument in 1940, affirming its cultural and historical importance.

Archaeological Rediscovery and Heritage Conservation (19th century – Present)

Systematic archaeological excavations initiated in the 19th century and continuing intermittently have uncovered extensive remains of Roman urban planning and early Christian architecture beneath the cathedral and throughout the historic center. Key discoveries include segments of the Via Annia, city walls and gates, Roman baths, the Basilica Apostolorum, private residences such as the Domus dei Signini, and the Roman theatre.

The archaeological site is organized along a walking route connecting principal remains, including the Porta Urbis, baths, city walls, and the Roman bridge on Via San Pietro. The area beneath the cathedral is managed by the Direzione Regionale Musei del Veneto, which facilitates public access and provides interpretive displays. Numerous artifacts from the site are curated in the Museo Nazionale Concordiese in nearby Portogruaro, while the Palazzo Municipale hosts exhibitions presenting recent findings and insights into the ancient city’s history.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Roman Foundation and Imperial Period (1st century BCE – 3rd century CE)

Following its establishment as Iulia Concordia around 42 BCE, the settlement functioned as a military and administrative center at a key crossroads. The population was socially diverse, comprising Roman settlers including soldiers, centurions, magistrates, artisans, and slaves, as evidenced by funerary inscriptions and monuments such as those in the “Sepolcreto dei militi.” Family structures likely adhered to Roman patriarchal norms, with elite households alongside working-class residents engaged in crafts and trade.

The economy was anchored in agriculture, exploiting the fertile alluvial plains for cereals, olives, and vineyards. Archaeological evidence of warehouses, workshops, and a specialized arrow-making industry indicates both domestic and industrial-scale production. The Lemene River port facilitated riverine and maritime trade, connecting Concordia to Aquileia and beyond. Urban amenities included paved streets, public baths, and a theatre, reflecting a structured civic environment.

Dietary remains and regional comparisons suggest consumption of bread, olives, fish, and locally produced wine. Clothing conformed to Roman styles, with men wearing tunics and cloaks, women donning stolas and pallas, and sandals as common footwear. Domestic interiors likely featured mosaic floors and painted walls, with houses incorporating courtyards, kitchens, and storage spaces. Markets offered a mix of local and imported goods, with transport by carts, boats, and footpaths.

Religious life combined traditional Roman pagan cults with military and civic rituals. Civic governance involved magistrates and councils, possibly duumviri, overseeing administrative and judicial functions. Concordia’s status as a colonia integrated it into the provincial system of Regio X Venetia et Histria, serving as a regional hub for military logistics, trade, and governance.

Late Antiquity and Early Christian Period (4th–5th centuries CE)

By the late 4th century CE, Christianity had become established in Concordia Sagittaria, marked by the construction of the Basilica Apostolorum. The population maintained continuity but increasingly embraced Christian beliefs, with affluent patrons such as Faustiniana sponsoring religious art and architecture. The social hierarchy evolved to include a prominent ecclesiastical elite alongside remaining civic officials and soldiers.

Economic activities persisted but were affected by the broader instability of the late empire. Agriculture and local crafts continued, though large-scale industrial production declined. The arrow-making industry likely diminished, while trade routes remained active but less vibrant. Funerary chapels and mosaics indicate sustained wealth among Christian families, who adorned their homes and religious spaces with symbolic imagery.

Diet and clothing remained broadly consistent with earlier Roman traditions, though Christian dietary practices may have influenced some habits. Domestic decoration incorporated Christian iconography alongside traditional motifs. Transport and commerce adapted to shifting political realities, with riverine routes remaining vital for movement of goods and people.

Religious practice centered on the Christian community, with the basilica serving as a focal point for worship, catechesis, and commemoration of local martyrs persecuted under Diocletian. The city became a bishopric seat, reflecting its ecclesiastical importance despite declining secular prominence. Civic structures shifted accordingly, with bishops assuming greater authority as imperial administration waned. The destruction wrought by Attila’s invasion in 452 CE accelerated urban decline but reinforced the religious identity of the site.

Early Medieval Period (6th–11th centuries CE)

Following the collapse of Roman imperial control, Concordia Sagittaria became part of the Lombard Duchy of Cividale and later the March of Friuli. The population contracted and urban life diminished due to repeated flooding and environmental challenges, as well as the reuse of Roman building materials. Family and social structures adapted to a more rural and ecclesiastically centered community, with the bishopric maintaining religious leadership.

Economic activities shifted toward small-scale agriculture and land reclamation, with limited craft production. The reuse of Roman stones in new constructions indicates a pragmatic approach to resources amid declining urban infrastructure. Trade and transport were reduced, relying more on local networks than long-distance commerce.

Diet likely remained based on cereals, legumes, and locally available produce, with less evidence of luxury imports. Clothing styles simplified in line with early medieval norms. Domestic spaces became more modest, with fewer decorative elements surviving; however, the construction of the Romanesque baptistery and the rebuilding of the cathedral attest to continued investment in religious architecture and art, including frescoes depicting Christ Pantocrator and saints.

Religious practice dominated daily life, with the cathedral complex serving as the spiritual and social center. Ecclesiastical authorities preserved relics of local martyrs and maintained liturgical traditions. Educational activities probably included Christian instruction and catechesis, though no direct evidence survives. Civic governance was largely subsumed under ecclesiastical and feudal structures, reflecting the broader transformation of post-Roman society.

Venetian Period

Under Venetian rule from 1420, Concordia Sagittaria integrated into the Republic’s political and economic framework, though it remained a small town with a primarily agrarian economy. The population engaged in farming, land reclamation, and local crafts, supported by the fertile plains and improved drainage. Social hierarchy included landowners, clergy, and municipal officials, such as those associated with the Palazzo Comunale built in 1523.

Diet and clothing reflected regional Renaissance and later styles, with agricultural produce forming the staple. Domestic interiors incorporated Renaissance and Baroque artistic influences, especially in religious buildings. Markets provided access to Venetian goods and local products, with transport relying on river navigation and road connections.

Religious life continued to center on the cathedral, which housed relics and artworks spanning centuries. The bishopric’s relocation in 1586 diminished ecclesiastical prominence locally, but the cathedral remained a cultural landmark. Civic administration was managed through Venetian-appointed officials and later Italian provincial authorities.

Archaeological Rediscovery and Heritage Conservation (19th century – Present)

The rediscovery of Concordia Sagittaria’s ancient remains from the 19th century onward has transformed understanding of its daily life and regional role. Archaeological excavations have revealed the complexity of its urban fabric, economic activities, and religious institutions, enriching knowledge of its inhabitants’ lifestyles across periods.

Current conservation efforts stabilize ruins and facilitate public engagement, while museums display artifacts illustrating domestic life, funerary customs, and artisanal production. Educational programs and exhibitions foster cultural appreciation and scholarly research, emphasizing the site’s continuous occupation from Roman colony to medieval bishopric.

Today, the site serves primarily as a cultural and educational resource, preserving the memory of its multifaceted past and highlighting the evolution of daily life, economy, and governance in northeastern Italy over two millennia.

Remains

Architectural Features

Concordia Sagittaria preserves a diverse array of architectural remains spanning from its late Republican foundation through the early medieval period. The city’s layout adheres to a Roman orthogonal grid, with a Decumanus Maximus (main east-west street) and Cardo Maximus (main north-south street) paved with trachyte stones. Defensive walls and gates, constructed during the Roman imperial era using ashlar masonry, enclosed the urban core. The alluvial terrain contributed to the burial and preservation of many structures beneath sediment layers.

The site encompasses civic, residential, military, and religious buildings, reflecting its complex functions. Over time, the urban fabric contracted, particularly after the 5th century CE, due to environmental factors such as flooding and river course changes. Roman construction techniques are evident in the use of basalt paving, ashlar masonry, and Roman concrete (opus caementicium) in public edifices. Early Christian and medieval structures often incorporate or overlay earlier Roman foundations, demonstrating continuity and adaptation of the urban space.

Key Buildings and Structures

Basilica Apostolorum (Early Christian Basilica)

Situated beneath the current cathedral in Piazza Cardinal Costantini, the Basilica Apostolorum dates to the late 4th century CE and forms part of a paleochristian complex that includes the Trichora martyrum sanctuary. The basilica features a nave and aisles, with mosaics bearing donor inscriptions. An elaborately decorated funerary chapel within the complex contains the sarcophagus of Faustiniana, a wealthy Christian woman. Constructed over earlier Roman structures, the basilica preserves remains from the 4th and 5th centuries CE. Access to the subterranean remains is provided through a ticket office adjacent to the cathedral.

Trichora Martyrum

This early Christian sanctuary, dating to circa 350 CE, was built to house relics of local martyrs who perished during the Diocletian persecutions around 304 CE. The tri-apsidal (three-apse) structure is integrated within the paleochristian complex beneath the cathedral and forms part of the archaeological area accessible under Piazza Cardinal Costantini.

Roman Road Via Annia (Urban Section)

A well-preserved segment of the Via Annia runs beneath Piazza Cardinal Costantini. This basalt-paved road, a major east-west artery intersecting with the Via Postumia, displays visible wheel ruts. The Via Annia also crossed the Roman bridge at the city’s western entrance. The road dates to the late 1st century BCE, coinciding with the colony’s foundation.

Roman Bridge on Via San Pietro

The Roman bridge on Via San Pietro, dating to the 2nd–3rd centuries CE, carried the Via Annia over the Reghena River. Its remains, including stone arches and piers characteristic of Roman engineering, are visible from outside and mark the ancient city’s western entrance.

City Walls and Gates

Remnants of the city walls, constructed during the Roman imperial period with ashlar masonry, are visible north of Piazza Cardinal Costantini. The eastern gate, known as Porta Urbis, is preserved near Via Faustiniana and aligns with a minor east-west decumanus. The northern gate stood at the intersection of Via Mazzini and Via Claudia; basalt paving and interpretive panels reconstruct its location. These fortifications enclosed the urban settlement’s core.

Roman Baths (Terme)

The ruins of a public bath complex are located on Via delle Terme, dating to the early imperial period. The baths include partially preserved rooms such as the caldarium (hot bath) and frigidarium (cold bath). Fresco fragments recovered from the site are exhibited in the Museo Nazionale Concordiese in Portogruaro. Interpretive panels accompany the visible remains, which are accessible from outside.

Domus dei Signini (Roman House)

Excavated near the intersection of Via Claudia and Via 8 Marzo, the Domus dei Signini is a residential building dating to the 1st–2nd centuries CE. The site includes domestic rooms, wells (pozzi), mosaic floors, and wall foundations. The domus is part of the ancient urban fabric and is accessible during scheduled openings.

Roman Theatre

The Roman theatre’s original semicircular perimeter is marked by a boxwood hedge near the Domus dei Signini. Although the superstructure no longer survives, its footprint is preserved within the archaeological park. The theatre was part of the city’s entertainment infrastructure during the Roman period, likely constructed in the 1st or 2nd century CE.

Archaeological Area of Piazza Cardinal Costantini

This area encompasses the early Christian basilica, a section of the Via Annia, and warehouses (magazzini) from the early imperial period. The warehouses, located near the urban stretch of Via Annia, are partially preserved and constructed with stone and brick. The archaeological area is managed by the Direzione Regionale Musei del Veneto, with access to underground remains through a ticket office.

Baptistery of Concordia Sagittaria

Adjacent to the cathedral, the baptistery was built in the 11th century in a Romanesque-Byzantine style. It features a Greek cross plan with three apses (tri-absidato). The interior contains frescoes dating from the late 11th to early 12th century, including depictions of Christ Pantocrator in the dome, angels, saints, Evangelists, and St. George fighting the dragon. The frescoes are fragmentary but notable for their vivid colors and light-filled space. The baptistery remains accessible without restrictions.

Cathedral of Santo Stefano Protomartire

The current cathedral was constructed in the 15th century, incorporating significant alterations from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Romanesque bell tower dates to circa 1150. The interior is austere, containing fragments of frescoes, a baptismal font, pulpit, and altar made with sculpted marble from earlier church phases. The Martyrs’ chapel within the cathedral houses relics of local martyrs and a painting by il Padovanino. The cathedral stands directly above the early Christian basilica remains.

Palazzo Municipale (Town Hall)

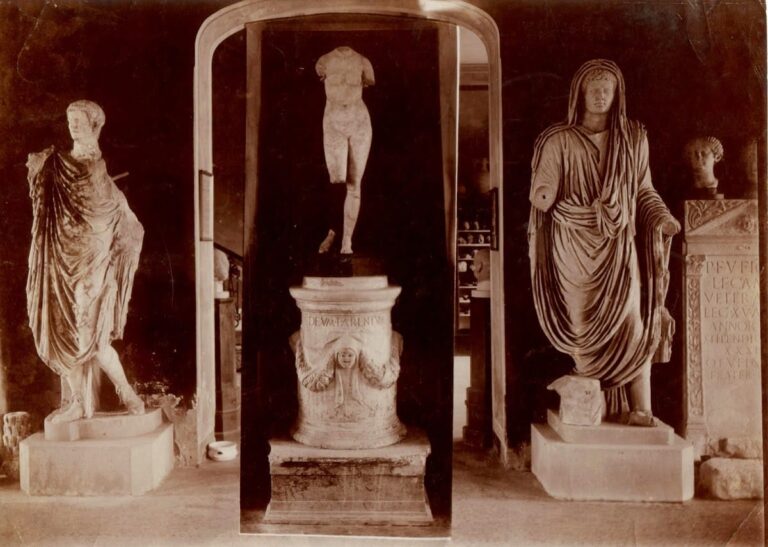

Overlooking the Lemene River near the cathedral, the Palazzo Municipale was built in 1523 with funds from Bishop Giovanni Argentino. It features a loggia that shelters Roman archaeological finds, including a monumental double tomb with two sarcophagi. The building houses a small local archaeological collection, accessible with limited opening hours.

Other Remains

Additional archaeological features include wells and domestic structures (pozzi romani) along Via dei Pozzi Romani. Surface traces and low walls of various Roman buildings are visible along the archaeological route. Although the forum is no longer extant, it was located along the Decumanus Maximus. The Cardo Maximus is partially reconstructed with trachyte paving stones at the intersection of Via Claudia and Via 8 Marzo. Warehouses (magazzini) from the early imperial period are preserved near the Via Annia urban stretch.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations at Concordia Sagittaria have yielded a variety of artifacts spanning from the late Republican period through the early medieval era. Pottery assemblages include amphorae and tableware, primarily locally produced but with some imported examples. Inscriptions on tombstones, dedicatory altars, and mosaics provide information on military personnel, public officials, and Christian donors such as Faustiniana.

Coins from multiple Roman emperors have been recovered, indicating continued occupation and economic activity into the late Roman period. Tools related to arrow production, consistent with the city’s historical association with archery, have been found in workshop areas. Domestic objects such as lamps and cooking vessels appear in residential contexts, while religious artifacts include sarcophagi, altars, and ritual vessels linked to early Christian worship.

Preservation and Current Status

The site’s preservation benefits from burial under alluvial deposits, which protected many structures from erosion. The Basilica Apostolorum and associated early Christian complex are well-preserved subterranean remains, stabilized for public access. City walls and gates survive in fragmentary form, with some sections consolidated but not fully restored. The Roman bridge remains visible but incomplete.

Roman baths and the Domus dei Signini are partially preserved, with fresco fragments conserved in local museums. The baptistery and cathedral are maintained as standing medieval structures, with the bell tower retaining original Romanesque masonry. Conservation efforts focus on stabilizing exposed ruins and preventing further deterioration. Ongoing archaeological research continues under the supervision of the Direzione Regionale Musei del Veneto.

Unexcavated Areas

Several parts of the ancient city remain unexcavated or poorly studied, including areas beyond the known city walls and sections of the presumed forum. Surface surveys and geophysical studies suggest buried remains beneath modern urban development. Excavations are limited by conservation policies and the presence of contemporary buildings. Future research aims to explore these zones further, subject to available resources and preservation constraints.