Byllis Archaeological Park: An Illyrian and Roman Urban Center in Albania

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.7

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: apolloniaarchaeologicalpark.al

Country: Albania

Civilization: Byzantine, Greek, Roman

Remains: City

Context

Bylis Archaeological Park is situated near the contemporary village of Hekal in Fier County, southwestern Albania. The site occupies a prominent plateau on the slopes of the Mallakastra mountain range, overlooking the Seman River valley. This elevated position provided strategic defensive advantages and extensive visibility over the surrounding terrain, facilitating control of regional routes and resources. The Mediterranean climate and fertile soils of the area supported agricultural activities that sustained the settlement throughout its occupation.

Archaeological investigations indicate that Byllis originated as a proto-urban settlement in the late Classical period, with significant development during the Hellenistic era beginning in the 4th century BCE. The city expanded and was fortified extensively, particularly in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE, and later experienced Roman colonization and Byzantine ecclesiastical prominence. Occupation persisted into late antiquity, with evidence of decline by the 6th century CE.

The site preserves substantial remains of its urban fabric, including defensive walls, public buildings, and religious structures.

History

Byllis Archaeological Park represents the remains of a fortified Illyrian settlement that evolved into a significant urban center through successive historical phases, including the Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine periods. Its commanding hilltop location overlooking the Seman River valley enabled it to exert control over local resources and trade routes, playing a notable role in regional power dynamics. The site’s history reflects broader political and cultural transformations in the western Balkans, from tribal confederations to Roman provincial administration and later Byzantine ecclesiastical governance.

Classical Period (4th century BCE)

During the 4th century BCE, the Mallakastër region was dominated by Illyrian tribes, notably the Bylliones, who established Byllis atop an earlier proto-urban settlement dating to the previous century. The city was fortified with extensive defensive walls constructed of isodomic ashlar masonry, extending approximately 2.25 kilometers and enclosing an area of about 30 hectares. These fortifications underscored the settlement’s strategic importance amid regional rivalries. The Bylliones controlled nearby bitumen mines at Selenica, a resource likely instrumental in the city’s foundation and economic sustenance. Epigraphic evidence, including inscriptions from the sanctuary of Dodona, attests to the tribe’s religious practices and concerns for safeguarding property, indicating an organized community with established cultic traditions.

Hellenistic Period (3rd–2nd century BCE)

In the Hellenistic era, Byllis emerged as the principal settlement of the Illyrian koinon (league) of the Bylliones, encompassing several hilltop centers in the lower Vjosa valley. The city’s political landscape was shaped by successive occupations and alliances involving Macedonian and Epirote rulers such as Cassander, King Glaukias, Pyrrhus of Epirus, and Illyrian kings including Mytilos. Greek cultural influence became prominent, as demonstrated by inscriptions in a northwestern Greek dialect and the adoption of Greek religious cults dedicated to deities like Zeus Tropaios, Hera Teleia, and Dionysius. Urban development included monumental public buildings such as a theater with a seating capacity of approximately 7,500, a stadium, an agora, and stoas, reflecting a polis-like civic organization. The bilingual population, evidenced by the reception of sacred envoys (theoroi) from Delphi, affirmed Byllis’s recognition as a Greek city. However, during the Roman-Illyrian war (169–168 BCE), the city’s shifting alliances led to its destruction by Roman forces after siding with Macedonian and Molossian opponents.

Roman Period (1st century BCE – 3rd century CE)

Following its devastation, Byllis was reestablished as a Roman colony around 30 BCE, designated Colonia Bullidensis. Incorporated into the Roman province of Epirus Nova, the city played a strategic role during the Great Roman Civil War. Reconstruction efforts included restoration of the defensive walls, theater, and other public edifices. Roman veterans settled in the colony, contributing to its social and economic revitalization. Epigraphic sources document a colonial senate (decurio) and duumviri magistrates overseeing civic administration, alongside augustales who sponsored imperial cult festivities. By the 2nd century CE, Byllis developed into a center of craft production, hosting workshops linked to northern Italian manufacturers. Wealthy inhabitants constructed elaborately decorated houses with mosaic floors. Infrastructure projects, such as roads and bridges financed by prominent citizens like Marcus Lolianus, integrated Byllis into regional transport and trade networks.

Late Antiquity and Byzantine Period (4th–6th centuries CE)

In late antiquity, Byllis functioned as an important episcopal seat within Epirus Nova, reflecting the Christianization of the city and its surroundings. Numerous basilicas featuring mosaic floors, baptisteries, and diaconicon chambers were constructed, including a large cathedral complex occupying an area comparable to the former agora. The city’s fortifications were rebuilt under Emperor Justinian I, with inscriptions crediting the engineer Victorinus for overseeing the works. Despite these defensive measures, Byllis suffered during barbarian invasions in the mid-6th century, notably during the Gothic War (547–551 CE). Subsequent Slavic raids around 586 CE led to the abandonment of the urban center and the transfer of the episcopal see to nearby Ballsh. Although some pottery production and limited urban functions persisted into the 6th century, the city did not recover its former prominence.

Post-Byzantine Period

After the 6th century CE, archaeological and historical evidence indicates that Byllis ceased to function as an inhabited urban site. The population relocated, and the city’s infrastructure fell into ruin. No significant occupation layers or inscriptions attest to continued settlement during the medieval period. The transfer of ecclesiastical authority to Ballsh marks the definitive end of Byllis as a functioning urban center. In subsequent centuries, the site remained in ruins, preserved primarily as an archaeological and cultural heritage location.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Classical Period (4th century BCE)

During its initial phase, Byllis was a fortified Illyrian settlement founded by the Bylliones tribe atop an earlier proto-urban site. The population was predominantly Illyrian, organized into tribal structures with emerging urban institutions. Control over the nearby bitumen mines at Selenica formed the economic backbone, supplemented by agriculture supported by the Mediterranean environment. Social organization likely centered on tribal elites managing resource exploitation. Religious life involved communal cultic activities, as indicated by inscriptions referencing worship at the Dodona sanctuary and protective rituals. The settlement’s layout adapted to the steep hilltop terrain, with clustered housing and defensive walls constructed through coordinated labor. Dietary staples probably included cereals, olives, and locally available fruits, supplemented by animal husbandry. Clothing styles conformed to Illyrian and regional Balkan traditions, likely comprising woolen tunics and cloaks.

Hellenistic Period (3rd–2nd century BCE)

Byllis transitioned into a polis-like urban center under strong Greek cultural influence, with a bilingual population integrating Greek language and customs alongside Illyrian heritage. Civic life was structured around formal institutions such as a council (demiourgoi), magistrates (prytanis, strategos), and assemblies, reflecting political integration within the Illyrian koinon of the Bylliones. Economic activities diversified to include agriculture, craft production, and continued control of mineral resources. Monumental public buildings—such as the theater, stadium, agora, stoas, and a peristyle temple—demonstrate investment in cultural and social amenities. Workshops likely operated at household or small industrial scales, producing goods for local use and regional exchange. Dietary evidence suggests increased access to Mediterranean staples like wine and olive oil. Clothing styles incorporated Hellenistic fashions, and domestic interiors featured mosaic floors and organized layouts, although detailed household archaeology remains limited. Religious practices combined Greek cults with local Illyrian elements, exemplified by the fire sanctuary Nymphaion and coin iconography. The city’s reception of theoroi from Delphi underscores its recognition as a Greek polis and its role in regional religious networks.

Roman Period (1st century BCE – 3rd century CE)

Following its reestablishment as a Roman colony, Byllis’s population included Roman veterans alongside local inhabitants, integrating Roman and Illyrian cultural elements. Civic governance was formalized with a colonial senate (decurio), duumviri magistrates, and augustales overseeing imperial cult activities. Prominent individuals, such as Marcus Lolianus, financed public works including roads and bridges. Economic life flourished with craft production workshops linked to northern Italy, indicating participation in broader imperial trade networks. Agriculture remained vital, supplemented by artisanal industries and commercial exchange facilitated by improved infrastructure. Domestic architecture featured elaborately decorated houses with mosaic floors, reflecting wealth accumulation among elite citizens. Dietary patterns incorporated Mediterranean staples consistent with regional norms. Public amenities such as baths, theaters, and porticoes supported social and cultural activities. Religious life combined traditional Greco-Roman deities with the imperial cult, reinforcing social cohesion and loyalty to Rome.

Late Antiquity and Byzantine Period (4th–6th centuries CE)

In late antiquity, Byllis evolved into a Christian episcopal center, with a population comprising clergy, local Christian communities, and remaining Romanized inhabitants. Social hierarchy incorporated ecclesiastical authorities alongside civic officials. Economic activities shifted toward sustaining ecclesiastical institutions and local needs, with continued but reduced pottery production and craftwork. Agricultural practices likely supported the urban population and clergy. Domestic life adapted to changing circumstances, with many houses repurposed or abandoned. Religious architecture flourished, with basilicas featuring mosaic floors, baptisteries, and diaconicon chambers. Secular domestic decoration declined as the city’s focus turned to ecclesiastical functions. Transportation relied on imperial-maintained road networks, though markets diminished in scale. Religious life centered on liturgical ceremonies, episcopal governance, and community gatherings. The construction of a large cathedral and multiple churches indicates an active Christian community. Despite fortification efforts under Justinian I, repeated barbarian and Slavic attacks precipitated demographic decline and eventual abandonment, with the episcopal see relocating to Ballsh.

Remains

Architectural Features

Byllis is situated on a plateau enclosed by extensive fortification walls originally constructed circa 350 BCE during the Illyrian period. These walls extend approximately 2.25 kilometers in length and measure about 3.5 meters in thickness. Built using isodomic ashlar masonry—carefully cut rectangular stone blocks laid in regular courses—the fortifications enclose roughly 30 hectares atop a steep hill. The walls underwent reconstruction during the Roman period and again in the 6th century CE under Emperor Justinian I, as documented by Greek inscriptions crediting the engineer Victorinus. After partial dismantling during the Pax Romana, the walls were rebuilt in the 5th century CE under Theodosius II, though the later fortifications enclosed only about one third of the original city area, reflecting contraction following barbarian incursions.

The urban layout follows a Hippodamian grid plan centered on a mid-3rd century BCE agora, which functioned as the city’s public square. Surrounding the agora are remains of civic and entertainment buildings, including a theater, stadium, gymnasium, and porticoes. The city’s architecture reflects a synthesis of Illyrian foundations with Hellenistic and Roman modifications, employing local stone and advanced masonry techniques. Residential quarters contain ruins of affluent houses with mosaic floors, indicative of prosperity during the 1st and 2nd centuries CE. The site also preserves early Christian basilicas and a large Byzantine cathedral complex, illustrating religious architectural developments into late antiquity.

Key Buildings and Structures

City Walls

The city’s defensive walls, constructed around 350 BCE during the Illyrian expansion, form a continuous circuit approximately 2.25 kilometers long and 3.5 meters thick. Built with isodomic ashlar masonry, the walls incorporated six gates, including two on the main road connecting Apollonia to Macedonia and Epirus. The walls were partially dismantled during the Pax Romana but underwent reconstruction in the late 4th and 5th centuries CE, reducing the enclosed area to about one third of the original. Inscriptions from the 6th century CE document repairs commissioned by Emperor Justinian I, overseen by the engineer Victorinus. The fortifications included towers and bastions, though many survive only as foundations or fragmentary masonry.

Theater

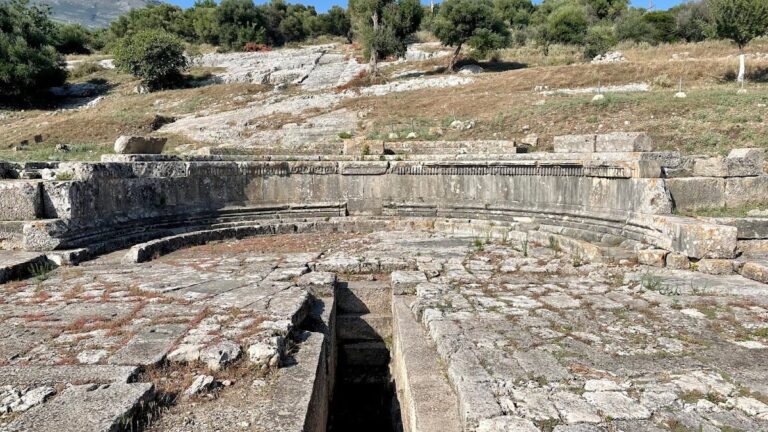

The theater, constructed in the mid-3rd century BCE, is located at the southeastern corner of the agora. It exploits the natural slope of the terrain and originally featured approximately 40 rows of stone seating, accommodating an estimated 7,500 spectators. Present remains include sections of the stone seats, load-bearing walls, and the orchestra’s base. The theater was rebuilt during the 1st century BCE Roman reconstruction phase, maintaining its original function. Its architectural composition, together with the adjacent great stoa and stadium, defined the agora’s public space. The masonry consists of local stone blocks, with some structural elements visible above ground.

Stadium

The stadium dates to the 3rd century BCE and is situated near the agora. It is partially preserved, with visible stone steps forming the seating area. The stadium is the second best-preserved in Albania after Amantia. Its layout follows typical Hellenistic athletic facilities, designed for foot races and other competitions. The structure was integrated into the city’s entertainment complex alongside the theater and gymnasium. Although only fragments survive, the stadium’s stone construction and tiered seating remain identifiable.

Agora and Porticoes

The agora was developed around the mid-3rd century BCE as the city’s central public square. It is surrounded by several public buildings, including the theater, stadium, gymnasium, and porticoes. The architectural plan follows the Hippodamian grid system, with streets intersecting at right angles. The great stoa, a large covered portico adjacent to the agora, was rebuilt during the 1st century BCE Roman period. The stoa’s remains include stone foundations and column bases. The agora functioned as a civic and commercial hub, with paved surfaces and defined boundaries visible in the excavated areas.

Basilica Churches and Byzantine Cathedral

Several early Christian basilicas have been excavated at Byllis, dating from the 4th to 6th centuries CE. These basilicas feature mosaic floors and carved architectural elements. Two basilicas include attached diaconicon chambers, spaces used for storing liturgical items, while one basilica (known as Basilica B) contains a baptistery. A large Byzantine cathedral complex was constructed in the 6th century CE, covering an area comparable to the old agora. This episcopal complex includes a nave, aisles, and associated chambers. Over twenty church locations have been identified in the surrounding region, indicating a significant Christian architectural presence during late antiquity.

Public Baths (Justinian’s Baths)

Public baths attributed to the Justinian period (6th century CE) are preserved within the archaeological park. These baths include rooms typical of Roman-Byzantine bath complexes, such as caldaria (hot rooms) and frigidaria (cold rooms), though detailed architectural plans remain incomplete. A separate Roman-period bathhouse, built by a member of the Saleni family, is known from inscriptions but has not yet been excavated. The preserved baths demonstrate the continuation of public sanitation facilities into late antiquity.

Treasury Warehouses

Remains identified as treasury warehouses are present at the site, though their precise dimensions and internal layouts have not been fully documented. These structures likely served as storage for public or private goods during the Roman and Byzantine periods. The masonry consists of stone blocks consistent with other civic buildings, but the lack of detailed excavation limits further description.

Domestic Buildings and Mosaics

Excavations have uncovered ruins of affluent houses dating primarily to the 1st and 2nd centuries CE. These domestic buildings feature mosaic-paved floors with geometric and figural motifs. The houses are constructed with stone walls and include multiple rooms arranged around courtyards. The presence of mosaics indicates a degree of wealth among residents, likely Roman veterans and local elites. Some houses show evidence of later modifications during the Byzantine period.

Road and Bridge Infrastructure

A Roman road connecting Byllis to the nearby settlement of Astacia (likely ancient Nicaea) has been documented. This road was financed by the Roman veteran Marcus Lolianus, as indicated by inscriptions. Along the route, a stone bridge crosses a river identified as Argia, possibly corresponding to the modern Povla or Gjanica river. The bridge’s foundations and some masonry remain visible, illustrating the city’s integration into regional transport networks.

Other Remains

The site includes remains of a gymnasium and a cistern dating to the Hellenistic period. The gymnasium’s foundations and associated walls have been partially excavated, revealing spaces for physical training and education. The cistern, constructed with waterproof masonry, provided water storage for the settlement.

Six gates punctuated the city walls, with two located on the main road from Apollonia crossing Byllis toward Macedonia and Epirus. These gates survive as foundations and partial wall segments. Surface inscriptions and architectural fragments confirm the presence of various public and religious buildings, although no temple or sanctuary has been excavated within the city limits. A fire sanctuary with an oracle named Nymphaion was located near the bitumen mines on the border with Apollonia, evidenced by coins and reliefs found in the vicinity.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations at Byllis have yielded numerous inscriptions spanning the Illyrian, Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine periods. These include dedicatory texts, official decrees, and construction records, such as those documenting Justinian I’s fortification works. Inscriptions reveal political institutions like the koinon of the Bylliones and Roman colonial governance bodies including the decuriones (colonial senate) and duumviri (magistrates).

Pottery finds encompass a variety of locally produced and imported wares from the 3rd century BCE through the 6th century CE. Amphorae, tableware, and cooking vessels have been recovered from domestic and public contexts. Coins from multiple periods, including Hellenistic rulers, Roman emperors, and Byzantine authorities, have been found, aiding chronological frameworks.

Tools related to agriculture and craft production have been uncovered, reflecting economic activities within the city. Domestic objects such as oil lamps and cooking implements appear in household assemblages. Religious artifacts include statuettes, altars, and ritual vessels associated with Greek and Illyrian cults during the Hellenistic period, as well as Christian liturgical items from late antiquity.

A notable discovery is a Hellenistic-era statue, possibly representing an Illyrian soldier or war deity, found in 2011 near the park during road works. This find contributes to understanding local artistic traditions and religious iconography.

Preservation and Current Status

The fortification walls remain visible in many sections, though some areas are fragmentary or reduced to foundations. The theater retains partial stone seating and structural walls, while the stadium’s stone steps survive in a fragmentary state. The agora and porticoes are preserved mainly as foundation outlines and low walls. Early Christian basilicas and the Byzantine cathedral complex survive as partial masonry and mosaic floors.

Restoration efforts have stabilized several structures, including the city walls and theater, using original materials where possible. Some reconstructions employ modern masonry to support fragile sections. Environmental factors such as vegetation growth and erosion pose ongoing challenges. Conservation is managed by Albanian heritage authorities, with systematic excavation and documentation continuing since the mid-20th century.

Unexcavated Areas

Significant portions of the urban area remain unexcavated, including residential districts beyond the central agora and sections of the city walls. The Roman-period bathhouse built by the Saleni family has not yet been uncovered. Surface surveys and geophysical studies suggest buried remains in peripheral zones, but modern land use and conservation policies limit extensive excavation. Future archaeological work is planned to focus on these areas, balancing research with preservation concerns.