Qasr Mshatta: An Umayyad Desert Palace in Jordan

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Country: Jordan

Civilization: Unclassified

Remains: Military

History

Qasr Mshatta is a ruined Umayyad palace located in the municipality of Amman, Jordan. It was constructed under the Umayyad Caliphate, an early Islamic kingdom that ruled much of the Middle East during the 7th and 8th centuries CE.

The site likely dates to the reign of Caliph Al-Walid II, who ruled briefly from 743 to 744 CE. Historical accounts indicate that Al-Walid II was exiled from the central caliphal court and spent time in the desert regions near Azraq Oasis, not far from where the palace stands. This exile may explain why the palace’s construction remained incomplete. Archaeological evidence, including a dated brick inscribed by Sulaiman ibn Kaisan, who lived between 730 and 750 CE, supports the attribution of the palace to this period and ruler.

Following the Umayyads, the Abbasid dynasty replaced them around 750 CE, shifting the political center from Damascus to Baghdad. This major change in governance and power dynamics likely led to the abandonment of Qasr Mshatta. The palace then ceased to function as a royal residence or administrative center.

In the early 20th century, part of the palace’s decorated southern facade was removed by Ottoman authorities under Sultan Abdul Hamid II and presented as a gift to German Emperor Wilhelm II. These architectural elements have since been exhibited in Berlin’s Islamic Art Museum. This removal has spurred calls from Jordanian scholars and officials for their repatriation, highlighting the palace’s significance as a cultural and historical monument.

Remains

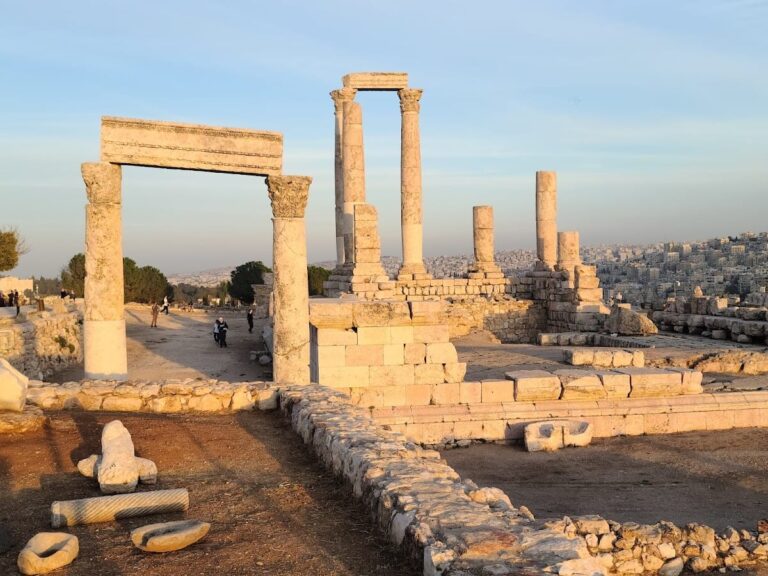

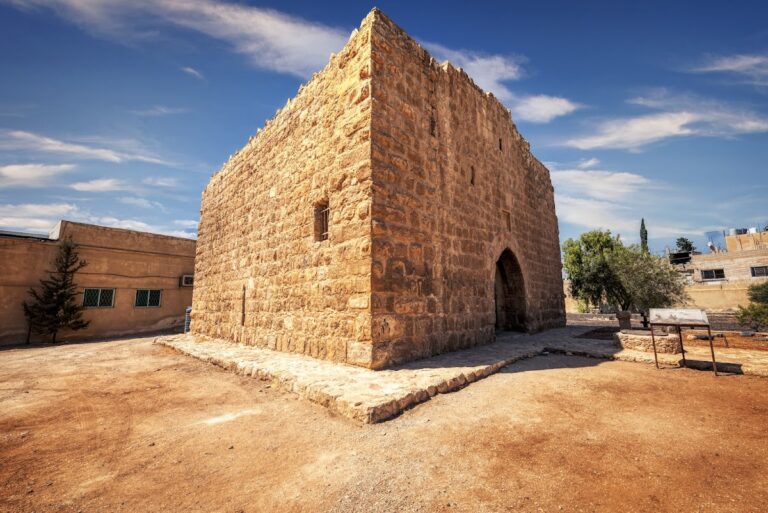

Qasr Mshatta occupies a square enclosure measuring about 144 to 150 meters on each side, made from limestone and fortified with 25 towers. Most towers are circular, except for two half-octagonal towers which frame the main entrance, blending defensive features with monumental design. The walls surround an area close to 22 dunams, organizing the space into a fortified desert palace.

Inside, the complex is divided into three long parallel sections, though only the central strip saw partial completion. At the southern end of this central area lies the Gateway Block, a series of rooms arranged around a small courtyard. Among these rooms is a small mosque, identified by a concave niche called a mihrab carved into its south wall, marking the direction toward Mecca for prayer.

The heart of the central portion contains a large rectangular courtyard featuring a pool at its center, providing a focal point for the palace. To the north, the reception hall wing is the only fully finished area, showcasing a vaulted basilica-style hall divided into three aisles by columns. This hall leads to a triconch-shaped throne room—a space with three semicircular niches—capped by a brick dome.

Adjacent to the reception hall are four residential suites, called buyut, notable for their barrel-vaulted ceilings and advanced ventilation system built into concealed air ducts. This feature reflects early attention to climate control and comfort within the palace.

The palace’s southern facade once displayed a richly carved limestone frieze stretching about 47 meters across its central portion. The decoration presents an intricate, continuous vine design interwoven with large rosettes, alongside a variety of animal and mythical creatures, including lions, griffins, peacock-like dragons known as simurgh, and unique half-horse hybrids. This imagery creates a paradisiacal effect typical of royal palaces, while the right side of the frieze transitions into smaller vegetal patterns near the mosque area, respecting Islamic aversion to figural imagery in religious settings.

This decorative ensemble combines influences from Classical Roman-Byzantine and Sasanian Persian art, representing an early merging of traditions that would shape later developments in Islamic art. Among the sculptural finds is a limestone statue of a reclining lion, approximately 72.5 centimeters tall and 121.5 centimeters wide, interpreted as a symbol of rulership, possibly intended for placement in the throne room.

Two incomplete sculptures depicting partially nude female figures were also discovered. These fragments show detailed drapery and include an Arabic Kufic inscription on one thigh. The figures may represent dancers or members of a prince’s harem, suggesting a blend of cultural and artistic themes within the palace’s decorative program.

The architectural design reflects inspiration from Roman and Syrian Christian traditions. The reception hall’s basilica plan and vaulted ceiling recall Roman public buildings, while the triple-arched portico echoes Roman triumphal arches. The throne room’s triple-iwan (rectangular hall or space vaulted with a barrel vault and walled on three sides) layout and domed roof further demonstrate the adaptation of regional architectural forms in a new Islamic context.

Constructed mainly from fired bricks for the inner walls and limestone for the enclosure and decorative elements, the palace remains partially preserved. Although much of the ornate facade was removed decades ago, the main structural components and some decoration remain on site, offering insight into Umayyad architectural and artistic achievements in the desert environment.