Ancient Athens

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.8

Popularity: Very High

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: odysseus.culture.gr

Country: Greece

Civilization: Byzantine, Greek, Roman

Remains: City

History

The site of Ancient Athens holds a central place in Greek history, reflecting its evolution from a fortified Bronze Age settlement into a major political, military, and cultural center. Its development influenced the broader Attica region and the Greek world, with its strategic location near the Saronic Gulf and Piraeus facilitating trade and defense. Athens’ historical trajectory encompasses phases of growth, conflict, and renewal, marked by significant political transformations and cultural achievements.

Archaeological and literary sources attest to Athens’ progression from a Mycenaean stronghold to a Classical polis that pioneered democratic governance and led Greek resistance against Persian invasions. The city later experienced Macedonian conquest, integration into the Roman Empire, and continued occupation through Byzantine and Ottoman periods, each leaving distinct archaeological and historical imprints.

Bronze Age and Early Iron Age

Human presence at Athens dates to prehistoric times, with substantial activity during the Late Bronze Age. Excavations reveal fortifications and burial sites consistent with Mycenaean cultural practices, indicating Athens functioned as a fortified center within the Mycenaean world. Unlike much of Attica, which was largely abandoned during the Dorian invasions, Athens maintained continuous occupation into the Early Iron Age. Literary tradition attributes the founding of the Acropolis to the mythical king Cecrops, who established Athena as the city’s patron deity following a legendary contest with Poseidon. During this era, the twelve Attic settlements were unified under Athens, possibly under the legendary figure Theseus, who is credited with organizing the population into three social classes: the aristocratic Eupatridae, the farmers and herders known as Geomoroi, and the artisans called Demiourgoi.

Archaic Period and the Emergence of Democracy (7th–6th centuries BCE)

The Archaic period witnessed the decline of monarchical rule, supplanted by aristocratic governance dominated by the Eupatridae. Legislative authority was exercised by officials known as Thesmothetes. The first codification of Athenian law occurred under Draco in 624 BCE; these laws were notably severe and remained in effect for approximately three decades before being superseded by Solon’s reforms in 594 BCE, which broadened political participation and laid the groundwork for democratic institutions. Social tensions manifested in events such as the failed tyranny attempt by Cylon in 632 BCE. Subsequently, Peisistratus established a tyranny in 560 BCE, succeeded by his sons Hippias and Hipparchus, who were the last tyrants of Athens.

Their overthrow in 510 BCE paved the way for Cleisthenes’ foundational reforms, which reorganized the population into ten tribes named after legendary heroes, subdivided into trittyes and demes. These reforms established the Boule, a council of 500 members selected by lot, and the Assembly (Ecclesia), which included all full citizens and functioned as the legislative and judicial authority, except in cases of murder and religious matters. Strategoi, or generals, were elected to military leadership roles.

Persian Wars and Early Classical Period (5th century BCE)

During the early 5th century BCE, Athens played a pivotal role in resisting Persian expansion. It actively participated in the Ionian Revolt (499 BCE), which provoked two major Persian invasions. The Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE, where Athenian forces under Miltiades secured a decisive victory, marked a turning point. In 480 BCE, Xerxes I led a massive invasion that resulted in the evacuation and sacking of Athens, as corroborated by archaeological strata and historical accounts.

The Greek naval victory at Salamis, commanded by Themistocles, was decisive in repelling Persian forces. Following the Persian withdrawal, Themistocles directed the reconstruction and fortification of Athens, including the erection of defensive walls. The exploitation of the Laurion silver mines during this century provided critical resources for building a formidable naval fleet, underpinning Athens’ maritime dominance.

Athenian Hegemony and the Age of Pericles (448–430 BCE)

The mid-5th century BCE represents Athens’ Golden Age under the leadership of Pericles, who held the strategos office from 445 BCE until his death in 429 BCE. This era was characterized by extensive public building programs on the Acropolis, including the construction of the Parthenon, symbolizing Athens’ cultural and political ascendancy. Athens led the Delian League, a maritime alliance that expanded its influence across the Aegean and parts of Greece. The city’s democratic institutions matured, and public works flourished, reflecting its status as the preeminent Greek power of the period.

Peloponnesian War and Decline (431–404 BCE)

The Peloponnesian War, commencing in 431 BCE, arose from opposition to Athenian dominance and pitted Athens and its naval empire against Sparta and its land-based allies. Early in the conflict, a devastating plague struck Athens, resulting in the death of Pericles and a significant portion of the population. Despite military successes such as the capture of Pylos (425 BCE) and victory at the Battle of Sphacteria, Athens suffered defeats at Delium and Amphipolis, where the general Cleon was killed.

The Sicilian Expedition (415–413 BCE) was a catastrophic military campaign that severely weakened Athens. Political instability included a brief oligarchic coup in 411 BCE, which was swiftly overturned to restore democracy. The war concluded in 404 BCE with Athens’ defeat and the imposition of the oligarchic Thirty Tyrants, who ruled with Spartan support until democracy was restored in 403 BCE by Thrasybulus.

Corinthian War and Second Athenian League (395–355 BCE)

Following Sparta’s ascendancy, Athens allied with former adversaries Thebes and Corinth in the Corinthian War (395–387 BCE) to challenge Spartan hegemony. Subsequently, Athens founded the Second Athenian League in 378 BCE to counter Spartan influence, attracting numerous Aegean islands and cities. Theban victory at the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BCE ended Spartan dominance, but Athens and other city-states opposed Theban hegemony, culminating in the Battle of Mantinea in 362 BCE, which terminated Theban supremacy.

Macedonian Domination and Late Classical Period (355–322 BCE)

The rise of Macedon under Philip II culminated in the defeat of Athens and its allies at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BCE, effectively ending Athenian independence. Athens became a member of the Macedonian-led League of Corinth and later came under the control of Antipater, who dissolved the democratic government in 322 BCE, replacing it with a plutocratic regime. Despite political subjugation, Athens retained its wealth and cultural significance, though it no longer functioned as an autonomous power.

Hellenistic Period

After Alexander the Great’s death, Athens participated in the Lamian War (322 BCE) against Macedonian rule but was defeated. Macedonian garrisons were stationed in the city, and Athens became part of the Macedonian kingdom under rulers such as Demetrius Poliorcetes and Antigonus Gonatas. The city allied with Sparta during the Chremonidean War (267–261 BCE), which ended in Macedonian victory and reassertion of control. During the Second Macedonian War, Athens aligned with Rome, signaling a shift in regional power dynamics.

Roman Period

Athens was peacefully incorporated into the Roman Empire, losing political independence but maintaining its cultural prestige. In 88 BCE, during the First Mithridatic War, Athenians invited Mithridates VI to liberate the city. The Roman general Sulla besieged and sacked Athens in 86 BCE, causing extensive destruction. Subsequently, Rome granted Athens special autonomous status in recognition of its intellectual heritage.

Emperor Hadrian (reigned 117–138 CE) completed the Temple of Olympian Zeus and commissioned numerous public buildings, including a library, gymnasium, and aqueduct. The Arch of Hadrian was erected in his honor. Wealthy Athenian Herodes Atticus sponsored significant monuments such as the Odeon of Herodes Atticus. In 267 CE, the city suffered major damage from an invasion by the Heruli, a Germanic tribe, leading to urban contraction. Athens remained an important intellectual center until Emperor Justinian closed the philosophical schools in 529 CE.

Byzantine, Medieval, and Ottoman Periods

Throughout the Byzantine era and subsequent medieval and Ottoman periods, Athens continued to be occupied, albeit with diminished political prominence. Architectural modifications attest to ongoing use and adaptation of ancient structures, reflecting changing religious and administrative functions. The city evolved into a regional center with ecclesiastical leadership, and archaeological evidence documents the layering of historical phases within the urban fabric. Despite the loss of its former status as a polis, Athens maintained cultural continuity and regional significance through these later periods.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Archaic Period and the Emergence of Democracy (7th–6th centuries BCE)

During the Archaic period, Athens’ population comprised native citizens organized into social strata: the aristocratic Eupatridae, farmers and herders (Geomoroi), artisans (Demiourgoi), and enslaved individuals supporting domestic and economic functions. Civic administration included magistrates such as the Thesmothetes and archons, reflecting a structured political hierarchy. Economic life centered on agriculture, with cultivation of olives, grapes, and cereals, alongside artisanal crafts like pottery and metalworking, often conducted in household workshops.

The Agora functioned as a marketplace for local produce and imported goods, including luxury ceramics and textiles. Domestic architecture featured simple layouts with rooms arranged around courtyards, and walls decorated with geometric motifs. The diet consisted primarily of bread, olives, figs, and occasional fish or meat. Religious observance focused on Athena, with festivals such as the Panathenaia reinforcing civic identity. Temples and altars began to appear on the Acropolis, marking the site’s growing religious importance. Athens’ political role expanded as it unified Attica’s twelve communities and developed democratic institutions, including the Boule and Assembly.

Persian Wars and Early Classical Period (5th century BCE)

The Persian invasions profoundly affected daily life, with the population comprising Athenian citizens, resident metics, and slaves. The 480 BCE sack caused disruption, but rapid rebuilding under Themistocles restored the city’s infrastructure. Military service was a central occupation, with many citizens serving as hoplites or rowers in the naval fleet funded by Laurion silver mining. Economic activities intensified, including expanded mining and maritime trade supporting both local needs and imperial ambitions. Workshops produced pottery, weaponry, and textiles at various scales.

The Agora thrived as a commercial and social center, with imported goods such as Attic black-figure pottery and luxury items from across the Aegean. Domestic interiors included painted plaster walls and mosaic floors in wealthier homes. The construction of defensive walls and the Long Walls improved transportation and security. Religious life intensified with temple rebuilding on the Acropolis, including early phases of the Parthenon. Festivals and rituals reinforced civic unity amid external threats. Athens emerged as a leading polis, coordinating the Delian League and asserting regional hegemony.

Athenian Hegemony and the Age of Pericles (448–430 BCE)

During Athens’ Golden Age, the population encompassed citizens, artisans, merchants, slaves, and resident foreigners. The democratic system matured, with remuneration for public office enabling broader participation. Prominent figures like Pericles influenced civic life, supported by elected generals and the Boule. Economic prosperity fueled monumental public works on the Acropolis, including the Parthenon, Propylaea, and Temple of Athena Nike, employing architects, sculptors, and laborers. Markets offered diverse goods, including imported spices, metals, and fine pottery.

Affluent homes featured elaborate mosaics and wall paintings. The Long Walls and well-maintained roads facilitated trade and military logistics. Religious festivals such as the Panathenaia and Dionysia were central to social cohesion, involving processions, sacrifices, and theatrical performances. Athens functioned as the political and cultural capital of its maritime empire, administering allied city-states through the Delian League. Its civic institutions embodied direct democracy, with the Assembly and courts playing pivotal roles. The city’s architectural grandeur and cultural patronage underscored its regional preeminence.

Peloponnesian War and Decline (431–404 BCE)

The prolonged Peloponnesian War disrupted daily life, causing demographic strain from plague and warfare. The population suffered significant losses among citizens, soldiers, and civilians, with social tensions exacerbated by political upheavals including oligarchic coups. Despite these challenges, agriculture and artisanal production persisted, albeit at reduced levels. Military service dominated male occupations, with naval and land campaigns taxing resources. The Sicilian Expedition’s failure severely impacted the economy and morale. Markets remained active but faced shortages and inflation.

Domestic life adapted to wartime conditions, with some households fortified or abandoned. Religious observances continued, though public festivals were sometimes curtailed. Civic institutions experienced interruptions, with democracy briefly suspended under the Thirty Tyrants before restoration. Athens’ regional influence waned, losing its empire and political dominance.

Corinthian War and Second Athenian League (395–355 BCE)

Post-war recovery involved rebuilding population and economy, reestablishing democratic governance and military alliances. The citizen body resumed political participation, with magistrates and councilors attested epigraphically. Economic activities revived, focusing on agriculture, craftsmanship, and renewed maritime trade. The Agora and marketplaces regained vibrancy, offering local produce and imported goods. Domestic architecture reflected modest prosperity, with some homes featuring decorative elements. Transportation infrastructure was maintained to support commerce and military readiness. Religious and cultural life flourished anew, with festivals reinstated and temples repaired. Athens led the Second Athenian League, asserting a cooperative regional role countering Spartan influence, though its power was diminished compared to the previous century.

Macedonian Domination and Late Classical Period (355–322 BCE)

Following defeat at Chaeronea, Athens’ political autonomy diminished under Macedonian oversight. The population remained predominantly Greek citizens, artisans, and slaves, with Macedonian officials and garrisons present. The democratic system was curtailed, replaced by oligarchic or plutocratic rule. Economic life continued with agriculture and crafts, though large-scale imperial ventures ceased. Markets operated primarily to satisfy local needs, with limited external trade. Domestic life showed continuity, though political uncertainty affected civic investment. Religious practices persisted, maintaining traditional festivals and temple cults. Athens retained cultural prestige as a philosophical and artistic center despite political subjugation, hosting schools such as the Academy and Lyceum.

Hellenistic Period

Athens experienced fluctuating control amid Macedonian conflicts and alliances. The population included native Athenians alongside Macedonian troops and administrators. Economic activities were modest, focusing on sustaining the urban population and supporting garrisons. Archaeological evidence indicates continued use of public spaces and religious sites, though large-scale construction was limited. Markets supplied everyday goods, with some imports reflecting ongoing trade connections. Domestic interiors remained functional, with few signs of major renovation. Religious festivals and cultural institutions endured, preserving Athens’ intellectual legacy. The city’s regional role shifted toward a secondary political actor within Hellenistic power struggles, maintaining symbolic importance rather than military or economic dominance.

Roman Period

Under Roman rule, Athens lost political independence but flourished as a cultural and intellectual hub. The population was ethnically diverse, including Romans, Greeks, and freedmen. Civic officials such as duumviri and local magistrates are attested epigraphically, overseeing administration and public works. Economic life expanded with imperial patronage. Construction of monumental buildings, Hadrian’s Temple of Olympian Zeus, library, gymnasium, and aqueduct, stimulated employment among architects, artisans, and laborers.

Wealthy citizens like Herodes Atticus sponsored theaters and odeons, enhancing cultural life. Markets offered a wide range of goods, from local agricultural products to imported luxuries via Piraeus harbor. Transportation included well-maintained roads and sea routes facilitating commerce and pilgrimage. Religious practices incorporated traditional Greek deities alongside Roman cults. The city hosted festivals blending cultural traditions. Athens’ status as a municipium with special autonomous privileges underscored its intellectual prestige within the empire.

Byzantine, Medieval, and Ottoman Periods

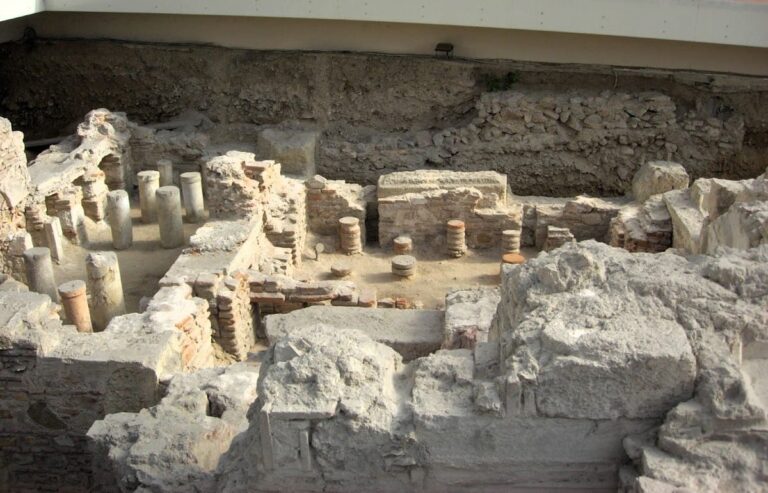

Throughout Byzantine and later periods, Athens’ population declined and diversified, including Greek Orthodox Christians, Latin occupiers, and Ottoman administrators. The city’s political role diminished, functioning as a regional center with ecclesiastical leadership. Economic activities focused on sustaining local needs, with limited craft production and small-scale agriculture. Archaeological layers reveal reuse and modification of ancient structures for residences, fortifications, and religious buildings. Religious life centered on Christian worship, with churches replacing pagan temples. Social customs adapted to changing rulers and cultural influences. Despite loss of former prominence, Athens remained a locus of regional administration and cultural continuity through these eras.

Remains

Architectural Features

The ancient city of Athens was enclosed by extensive defensive walls, initially constructed during the Bronze Age and subsequently rebuilt and expanded over centuries. The city walls formed a circuit approximately 1.5 kilometers in diameter, with suburbs extending beyond them at the city’s peak. The Long Walls, constructed in the 5th century BCE, consisted of two parallel fortifications extending about seven kilometers from Athens to the port of Piraeus, separated by a narrow corridor. A third fortification, the Phalerian Wall, extended roughly 6.5 kilometers eastward to the port of Phalerum. The entire defensive system, including city and harbor walls, measured nearly 35 kilometers in length.

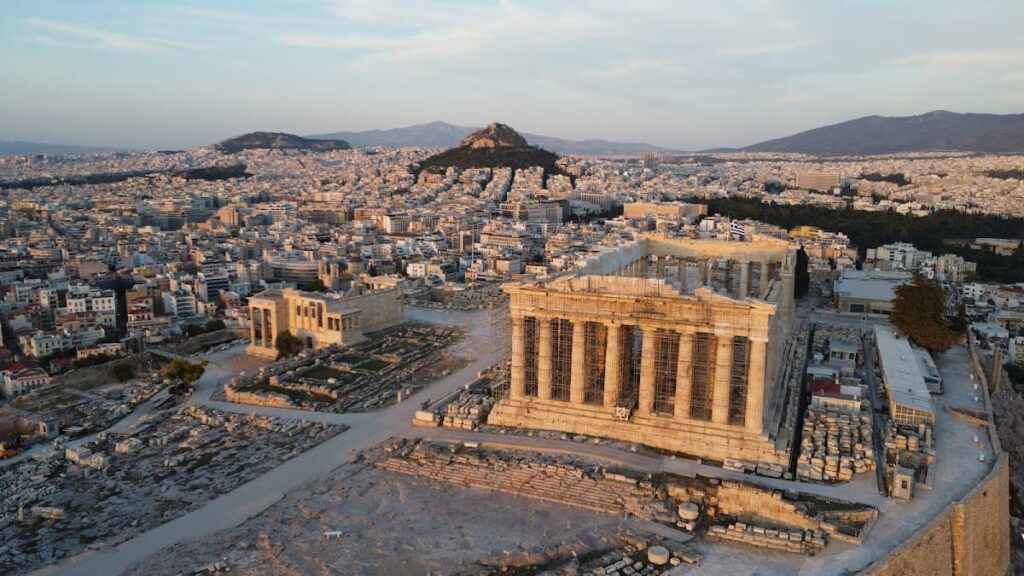

The Acropolis, a rocky plateau approximately 50 meters high, 350 meters long, and 150 meters wide, was naturally steep on all sides except the west. It was originally encircled by a Cyclopean wall attributed to the Pelasgians; the northern section, known as the Pelasgic Wall, survives from the Peloponnesian War era, while the southern portion was rebuilt by Cimon in the 5th century BCE. The sole accessible entrance on the west side featured the Propylaea, a monumental gateway constructed under Pericles in the mid-5th century BCE. The Acropolis summit housed several temples and monumental sculptures, including the Parthenon and the Erechtheion.

The lower city extended around the Acropolis, occupying a plain interspersed with hills such as the Areopagus, Pnyx, and Mouseion. The urban layout comprised a network of streets, including the Panathenaic Way and Piraean Street, connecting key gates and public spaces. The city contained multiple districts and demes, with residential, religious, and civic buildings distributed across the terrain.

Key Buildings and Structures

Architectural Features

The ancient city of Athens was enclosed by extensive defensive walls, originally constructed in the Bronze Age and rebuilt over subsequent centuries. The city walls formed a circuit approximately 1.5 kilometers in diameter, with suburbs extending beyond them at the city’s height. Notably, the Long Walls, built in the 5th century BCE, consisted of two parallel fortifications stretching about 7 kilometers from Athens to the port of Piraeus, with a narrow passage between them. A third wall, the Phalerian Wall, extended roughly 6.5 kilometers eastward to Phalerum. The entire defensive circuit, including city walls and harbor fortifications, measured nearly 35 kilometers in length.

The Acropolis, a rocky plateau about 50 meters high and 350 meters long, was naturally steep on all sides except the west. It was originally surrounded by a Cyclopean wall attributed to the Pelasgians, with the northern section (the Pelasgic Wall) surviving from the Peloponnesian War era and the southern part rebuilt by Cimon in the 5th century BCE. The only accessible entrance on the west featured the Propylaea, constructed under Pericles in the mid-5th century BCE. The summit contained several temples and monumental sculptures, including the Parthenon and the Erechtheion.

The lower city spread around the Acropolis, occupying a plain with several hills such as the Areopagus, Pnyx, and Mouseion. The urban layout included a network of streets like the Panathenaic Way and Piraean Street, connecting key gates and public spaces. The city contained multiple districts and demes, with residential, religious, and civic buildings distributed across the terrain.

City Walls and Gates

The city walls, dating from the Bronze Age and rebuilt through the Classical period, enclosed Athens with a circuit of approximately nine kilometers. The Long Walls, constructed in the 5th century BCE, connected Athens to Piraeus, ensuring secure access to the sea. The Phalerian Wall, also from the Classical period, linked the city to the eastern port of Phalerum. Several gates punctuated the walls, including the Dipylon Gate on the west, which served as the main entrance to the inner and outer Kerameikos and led toward the Academy. Other gates included the Sacred Gate, Knight’s Gate, Piraean Gate, Melitian Gate, Gate of the Dead, Itonian Gate, Gate of Diochares, Diomean Gate, and Acharnian Gate, each providing access to specific districts or external routes. Foundations and partial masonry of these gates survive, offering insight into their construction and urban function.

Acropolis

The Acropolis complex, primarily developed in the 5th century BCE, features the Propylaea gateway built under Pericles, marking the western entrance. Adjacent to it stands the Temple of Athena Nike, a small Ionic temple from the same period. The Parthenon, constructed between 447 and 432 BCE, dominates the summit; it is a large Doric temple dedicated to Athena Parthenos.

North of the Parthenon lies the Erechtheion, built circa 421–406 BCE, comprising three distinct sanctuaries: the temple of Athena Polias, the main Erechtheion sanctuary dedicated to Erechtheus, and the Pandroseion. Between the Parthenon and Erechtheion stood the colossal bronze statue of Athena Promachos, documented in ancient sources though no physical remains survive. The Acropolis was enclosed by fortifications, including the Pelasgic Wall to the north and the Cimonian Wall to the south.

Agora

The Agora, located northwest of the Acropolis and north of the Areopagus hill, served as the city’s marketplace and civic center. It contains several important structures dating mainly to the Classical period. The Bouleuterion, the council house, is situated on the west side of the Agora. Nearby stands the Prytaneion, a round building constructed around 470 BCE by Cimon, used for official meals and sacrifices.

The Metroon, a temple dedicated to the mother of the gods, is also on the west side. Several stoae (covered colonnades) line the Agora, including the Stoa Basileios, which housed the court of the King-Archon, the Stoa Eleutherios dedicated to Zeus Eleutherios, and the Stoa Poikile on the north side, decorated with frescoes depicting the Battle of Marathon. The Temple of Hephaestus, a well-preserved Doric temple from the 5th century BCE, stands to the west of the Agora, while the Temple of Ares is located to the north.

Theatre of Dionysus

On the southeast slope of the Acropolis lies the Theatre of Dionysus, constructed in the 5th century BCE. It is a large open-air theatre with a semicircular seating area carved into the hillside. The theatre was the principal venue for dramatic performances in classical Athens. Remains include stone seating tiers and parts of the orchestra area.

Odeons

Two ancient odeons are documented near the Acropolis. One, located near the fountain Callirrhoë, dates to the Classical period. A second odeon, built by Pericles in the 5th century BCE, lies close to the Theatre of Dionysus on the southeast slope. The Odeon of Herodes Atticus, constructed in 161 CE during the Roman period, is a large stone theatre with a vaulted roof, partially preserved and still standing.

Temple of Olympian Zeus

Situated southeast of the Acropolis near the Ilissos River and the Callirrhoë fountain, the Temple of Olympian Zeus was begun in the 6th century BCE but remained unfinished for centuries. Emperor Hadrian completed its construction in the 2nd century CE. The temple features Corinthian columns and a large rectangular plan, with several columns still standing.

Panathenaic Stadium

Located south of the Ilissos River in the district of Agrai, the Panathenaic Stadium was the venue for athletic competitions during the Panathenaic Games. The stadium’s origins date to the Classical period, with significant Roman-era renovations. Its elongated shape and seating areas are partially preserved.

Inner and Outer Kerameikos

The Inner Kerameikos lies west of the city, extending north to the Dipylon Gate, which separates it from the Outer Kerameikos. The Outer Kerameikos, northwest of the city, was a prominent suburb and burial area for fallen Athenians. The Academy, located six stadia from the city in the Outer Kerameikos, is also documented archaeologically.

Cynosarges and Lyceum

East of the city across the Ilissos River, the Cynosarges gymnasium was dedicated to Heracles and is known as the teaching site of the Cynic philosopher Antisthenes. The Lyceum, also east of the city, was a gymnasium sacred to Apollo Lyceus and the location where Aristotle taught. Both sites have archaeological remains consistent with gymnasium complexes.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations have uncovered a wide range of artifacts spanning from the Late Bronze Age through the Ottoman period. Pottery includes amphorae, tableware, and storage jars from Mycenaean, Archaic, Classical, Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine contexts. Inscriptions on stone and pottery fragments record laws, dedications, and public decrees, notably from the Classical and Hellenistic periods.

Coins from Athenian, Macedonian, and Roman issuers reflect the city’s changing political affiliations. Tools related to agriculture, crafts, and construction have been found in domestic and workshop areas. Domestic objects such as lamps, cooking vessels, and furniture fragments appear in residential quarters. Religious artifacts include statuettes, altars, and ritual vessels from various cults active in the city. These finds derive from stratified deposits in urban layers, sanctuaries, and burial grounds, illustrating continuous occupation and diverse economic and religious activities.

Preservation and Current Status

The preservation of Ancient Athens’ remains varies considerably. The Parthenon and Erechtheion on the Acropolis retain substantial structural elements, though some parts are fragmentary. The Propylaea and Temple of Athena Nike survive in partial form. City walls and gates exist as foundations and masonry sections. The Theatre of Dionysus and Odeon of Herodes Atticus preserve seating and architectural features to varying degrees.

The Temple of Olympian Zeus retains several standing columns. Agora buildings survive as foundations and partial walls, with some stoae columns extant. Conservation efforts since the 20th century have stabilized many structures, with some restoration employing modern materials. Excavations continue selectively due to urban overbuilding, with many remains stabilized but not fully restored. No specific reports of environmental or human threats are detailed in the available sources.

Unexcavated Areas

Significant portions of the ancient city remain unexcavated beneath modern Athens. Stratified deposits survive under urban layers, necessitating targeted excavation strategies. Some districts, including parts of Melite, Skambonidai, and Koele, are poorly studied archaeologically. Surface surveys and historical maps suggest buried remains in these areas, but extensive excavation is limited by contemporary urban development. Current conservation policies prioritize stabilization over intrusive digging in many zones.