Serravalle Castle: A Medieval Fortress in Switzerland

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.5

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: castello-serravalle.ch

Country: Switzerland

Civilization: Unclassified

Remains: Military

History

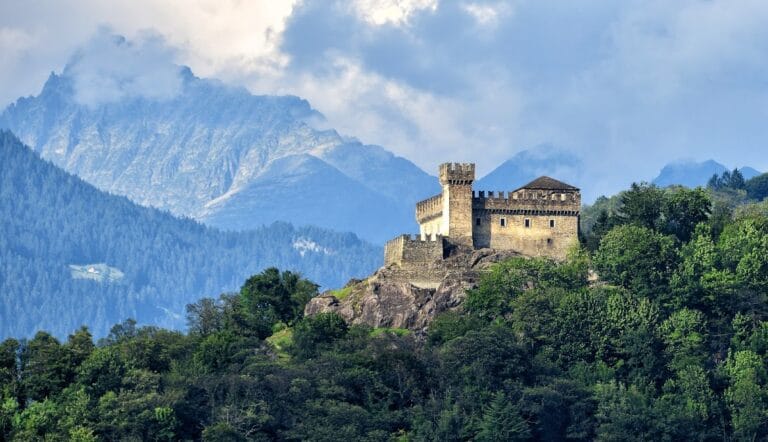

The ruins of the medieval castle Serravalle are located near the village of Semione in Switzerland. This fortress was established by medieval European builders and served as a stronghold in the Blenio Valley region.

The earliest origins of the castle may date to the Carolingian era around 900 AD, according to radiocarbon dating and historical accounts. However, its first known documentary mention comes from 1162, when Alcherius da Torre is recorded as the castle’s lord. He supported the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa, who appointed him avogadro (a type of bailiff) of the Blenio Valley. Emperor Frederick Barbarossa is said to have stayed at Serravalle castle in 1176 during his military campaign in Italy. This period marks the castle’s early role as a military and administrative center under imperial authority.

In 1182, tensions arose between the castle’s lord and the local population. The inhabitants formed the “Patto di Torre,” an alliance aimed at removing the lord’s control. After a siege, Artusio da Torre surrendered and the castle was intentionally destroyed. For about fifty years, these ruins stood abandoned, reflecting the inhabitants’ desire to resist regional domination.

Around 1220 to 1230, the fortress was rebuilt and expanded under the direction of the Orelli family. This family assumed lordship and became vassals to the powerful rulers of Milan. With this reconstruction, Serravalle reemerged as the political heart of the Blenio Valley. Over the next century, the castle underwent further enlargement. Important construction phases during the 13th and 14th centuries included building a massive fortified tower, known as a donjon, around 1250, and adding a semicircular defensive tower in the 1300s.

Control of the castle later shifted to the Counts of Oleggio and eventually passed to the Visconti family, who ruled the valley until 1380. That year, the Visconti sold their rights to the Pepoli family from Bologna. However, following the death of Duke Gian Galeazzo Visconti in 1402, local unrest led to a violent revolt. In this uprising, the castle was attacked and destroyed once more, and the lord Taddeo Pepoli was killed. Unlike before, the fortress was never rebuilt after this second destruction. Changing military strategies prioritized defenses closer to Bellinzona, reducing Serravalle’s strategic importance.

Excavations in the 20th and early 21st centuries have revealed the castle’s rich historical layers. Investigations uncovered luxury items such as Venetian glass and Italian ceramics, demonstrating a high standard of medieval life influenced by Northern Italian culture. Finds of arrowheads, crossbow bolts, heavy siege stones, and remains of a large trebuchet—a type of medieval catapult—confirm the castle’s involvement in sophisticated warfare, notably during the 1402 siege. The castle’s name, meaning “mountain pass barrier,” reflects its key role in controlling access across the Lukmanier Pass, a strategic alpine route.

Remains

The ruins of Serravalle castle sit atop a broad rocky ridge, about 391 meters above sea level. The complex consists of two clear construction phases. The earliest period, dating roughly from 900 to 1180, leaves only a few foundation fragments. Most surviving structures belong to the second phase, from approximately 1224 until the castle’s destruction in 1402. This later development includes a main fortress and a southern outer bailey, which is a fortified courtyard area. The outer bailey extends along a terrace about 90 by 30 meters in size, though medieval walls there have largely disappeared beneath dense vegetation.

Entrance to the site was carefully controlled. Access began from the north via an outer gate on the east side. Visitors would then make a sharp right turn to cross a drawbridge before reaching the main courtyard. Inside, defenses included multiple gates, narrow passages called zwingers designed to trap attackers, and intermediate ditches, adding layers of protection before entering the core castle area.

The main fortress divides into several sections. The southern wing contains rooms whose original purposes remain uncertain. Central to the castle was a large courtyard featuring vestiges of three thick columns, which once supported an expansive covered hall with a staircase leading to a prominent two-story building. The northern part housed the core living and defensive structures, including a large round donjon tower. The donjon’s walls were approximately two meters thick. It was not physically attached to the main castle building, suggesting that access to its upper floors was by a wooden bridge connecting from the northern wing.

To the west of the courtyard lay a long kitchen wing, identifiable by a sizable oven and a cellar-like lower room used for storage. Later construction added a flanking tower on the west side of the kitchen, bolstering the castle’s defenses in that direction. The entire complex was built primarily using stone masonry. Different construction phases are visible through numerous changes in the wall joints, reflecting centuries of modifications and repairs. Today, preservation varies from foundation remains to collapsed rubble.

At the southwestern edge of the outer bailey stands the chapel of Santa Maria del Castello. Incorporated into the castle’s ring wall, this chapel was originally dedicated to Saint Martin and is documented as early as 1339. The structure visible today mostly dates from renovations in the 16th and 18th centuries. Inside, late 16th-century frescoes decorate the choir area, painted by Giovanni Battista Tarilli. Among these are a late Gothic image of Saint Christopher on the north wall and a depiction of Justice on the west facade, linked to the chapel’s historical association with executions.

Archaeological digs have uncovered a wealth of artifacts indicating a wealthy lifestyle influenced by Northern Italy. Finds include Venetian glassware, colorful majolica ceramics, coins, jewelry, and fragments of painted wall decorations from the 13th century. Weapons discovered at the site range from arrowheads and crossbow bolts to large siege projectiles weighing up to 104 kilograms. A remarkably well-preserved trebuchet, a heavy siege engine of Byzantine origin, was used during the siege in 1402. These military artifacts highlight the castle’s active role in medieval warfare and its importance as a military bastion in the region.