Qasr Kharana: An Umayyad Desert Castle in Jordan

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.3

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Country: Jordan

Civilization: Unclassified

Remains: Military

History

Qasr Kharana is situated near the municipality of Amman in modern-day Jordan. It was constructed during the period of the Umayyad dynasty, with a surviving inscription dating its partial completion to November 24, 710 CE. This desert castle stands near the border with Saudi Arabia and reflects the architectural and cultural milieu of early Islamic rule in the region.

The origins of Qasr Kharana may extend slightly before the Umayyad period, as archaeological findings include three Greek inscriptions engraved on stones of uncertain provenance. These inscriptions suggest the possibility of earlier Greek or Byzantine activity at the site, although no firm evidence confirms a preceding building directly beneath or incorporated into the castle.

Throughout the centuries following its construction, Qasr Kharana underwent a gradual decline, eventually falling out of use and suffering damage from several earthquakes. The castle’s initial role has been debated among scholars over time. Early historians mistakenly identified it as a Crusader castle or military fortress, and others speculated that it functioned as an agricultural outpost or a roadside inn to serve caravans crossing the desert. Contemporary research tends to favor the view that the site served as a gathering place for regional Bedouin leaders, hosting meetings and negotiations rather than functioning primarily as a military or commercial base.

In the late 19th century, the castle first attracted detailed attention from modern explorers. In 1896, Sir John Edward Gray Hill published a descriptive account but misread certain architectural elements, which contributed to the initial misclassification of the structure as a Crusader fortification. Around 1900, Alois Musil, a Czech geographer, visited the site multiple times and supported the idea that Qasr Kharana was a fortress, even adding battlements in his illustrative renditions despite the absence of archaeological proof for such features.

Scholarly study deepened with the 1922 publication by Antonin Jaussen and Raphaël Savignac, offering a more critical examination of the castle. Later, in 1946, Nabia Abbott translated and analyzed the inscriptions found at Qasr Kharana, conclusively dating the building to the early 8th century, no later than 710 CE. The site underwent restoration efforts in the late 1970s, which involved the introduction of modern materials such as cement and plaster. Academic inquiry continued with Stephen Urice’s doctoral dissertation, completed in 1987, providing detailed analysis of the site’s architecture and historical context.

Today, Qasr Kharana remains an important example of Umayyad desert architecture, reflecting both the cultural interactions and political environment of early Islamic Jordan.

Remains

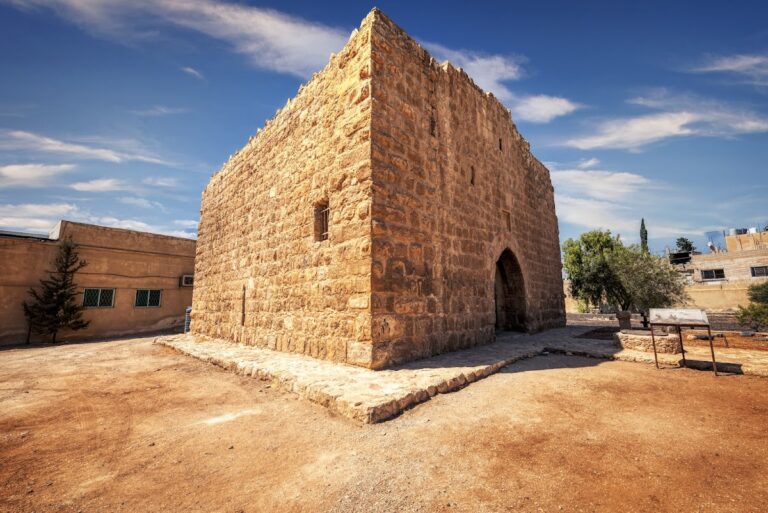

Qasr Kharana is a robust, nearly square structure measuring roughly 35 meters on each side, positioned atop a ridge that commands wide views over the surrounding landscape of Wadi al-Kharana. The building covers an area of about 1,225 square meters and is constructed primarily from irregular limestone blocks held together with a clay-based mortar. Distinctive horizontal courses of flat stones decorate the exterior walls near the upper third, forming a zigzag pattern that adds an ornamental aspect to the otherwise solid and simple appearance.

At each corner of the castle, three-quarter-round buttresses provide structural stability, while additional quarter-round buttresses flank the rounded main portal on the southern facade. The other walls are reinforced by half-round buttresses placed at regular intervals, lending rhythmic articulation to the castle’s outer surfaces. Access to the interior is gained through a single entrance on the south wall, opening into a narrow passageway measuring approximately 3.5 by 9.15 meters. This corridor leads directly into a central courtyard about 12.65 by 12.95 meters in size. In the courtyard’s center is a rainwater pool, known locally as a houz, designed for water collection in the arid environment.

Inside, Qasr Kharana contains around 60 rooms arranged over two floors, organized into units called bayts. Each bayt includes a main room surrounded by smaller chambers, with all doorways opening onto the courtyard rather than connecting directly to one another, which reflects a careful architectural planning of private and communal spaces. On the east and west sides of the courtyard, bayts consist of eight rooms each, while the north side features a suite of seven rooms. Larger halls flank the entrance passage on either side, each approximately 12.8 by 8 meters, believed to have served as stables and storage areas.

Two staircases positioned at the southwest and southeast corners of the courtyard lead to the upper level. Each staircase has two flights with an intermediate landing and opens onto porticos and corridors that provide access to the roof terrace. The first-floor layout largely mirrors that of the ground floor, though room sizes and orientations vary slightly. On the south side, two five-room bayts occupy each corner, separated by a larger central room.

The castle’s interior spaces are supported by a system of transverse arches that carry barrel vaults. These arches rest on bearing arms instead of being integrated into load-bearing walls, a construction technique that adds flexibility and may have improved resistance to earthquakes. Wooden lintels were employed to provide additional structural resilience through flexibility.

Narrow slits punctuate the walls, once mistakenly interpreted as defensive arrow slits but now understood to function for ventilation and to reduce dust and excessive sunlight. These slits are positioned and shaped to enhance airflow using a principle similar to the Venturi effect, thus cooling the interior.

Decorative plasterwork decorates interior rooms, particularly on the upper floor, where pilasters, medallions, and blind niches provide elegant embellishment. One south-side room was reserved for prayer, reflecting the religious sensibilities of the castle’s occupants. The overall architectural style blends influences from Syrian, Parthian, and Sasanian traditions, combined with early Islamic ideas about separating public and private areas. This is evident in the arrangement of windows, terraces, and bayts.

No additional buildings or water-capturing structures such as wells or dams are found on the site. Instead, water was collected from simple gravel pits nearby in the wadi, relying on rainwater gathering, which sufficed for the castle’s limited needs but could not support large or prolonged settlement.