Pompeii: Preserved Roman City Near Mount Vesuvius

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.7

Popularity: Very High

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: pompeiisites.org

Country: Italy

Civilization: Roman

Remains: City, Civic, Domestic, Economic, Entertainment, Military, Religious, Sanitation

Context

The Archaeological Park of Pompeii is situated near the contemporary city of Pompei within the Metropolitan City of Naples, in southern Italy. Positioned on a coastal plain along the Bay of Naples, the site lies at the base of Mount Vesuvius, whose volcanic activity profoundly influenced the region’s environment and history. The surrounding terrain features low hills and fertile volcanic soils, which supported intensive agriculture and shaped settlement patterns. Proximity to the sea facilitated maritime connections with neighboring Campanian communities and broader Mediterranean trade networks.

Originally settled in the 7th to 6th centuries BCE by Oscan-speaking groups, Pompeii evolved through successive cultural and political phases, including Samnite domination and eventual incorporation as a Roman municipium in the late Republic. The city expanded significantly during Roman rule, reflecting its integration into imperial administrative and economic systems. Its occupation was abruptly terminated in 79 CE when the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius buried the urban fabric beneath volcanic ash and pumice, preserving a unique archaeological record of Roman urban life.

Following centuries of burial and obscurity, Pompeii was rediscovered in the 18th century, leading to extensive excavations that have revealed well-preserved streets, buildings, frescoes, and artifacts. The site’s preservation offers unparalleled insight into ancient urbanism, social organization, and daily activities. Ongoing conservation efforts address challenges posed by exposure to weather, tourism, and earlier excavation practices, aiming to safeguard Pompeii’s exceptional cultural heritage.

History

The Archaeological Park of Pompeii encompasses the remains of a city whose history reflects the complex cultural and political dynamics of Campania from the early Iron Age through the Roman Imperial period. Its strategic location on the Bay of Naples enabled integration into regional trade and political networks, while its fortunes were shaped by successive Oscan, Samnite, and Roman influences. Pompeii’s development from a cluster of Italic villages into a Roman municipium illustrates broader processes of cultural assimilation and urbanization in ancient Italy, culminating in its sudden destruction in 79 CE.

Early Settlement and Pre-Roman Period (8th–5th century BCE)

Pompeii’s origins trace to the 8th century BCE when Oscan-speaking peoples established five distinct villages in the area, a fact possibly reflected in the city’s name derived from the Oscan term for “five.” By the mid-8th century BCE, Greek settlers in Campania introduced Hellenic cultural elements, including the cult of Apollo and Doric architectural forms, as evidenced by the construction of a temple near the future forum site. By the early 6th century BCE, these villages had coalesced into a single fortified settlement, enclosed by a tufa city wall known as the pappamonte wall, which encompassed both urban and agricultural zones, indicating early wealth and territorial control.

During the 6th century BCE, Etruscan influence extended to Pompeii without military conquest, incorporating the city into the Etruscan League of cities. Archaeological evidence includes Etruscan inscriptions and a necropolis dating to this period. Residential architecture from this era features Tuscan-style atria, and the city’s defenses were reinforced in the early 5th century BCE with orthostate walls composed of vertically set Sarno limestone slabs filled with earth. This phase reflects Pompeii’s integration into the complex cultural milieu of pre-Roman Campania, blending Italic, Greek, and Etruscan traditions.

Samnite Period (c. 450–290 BCE)

The 5th century BCE witnessed partial abandonment of some urban areas and a decline in votive offerings at sanctuaries such as the Temple of Apollo, suggesting social and economic shifts. Around 424 BCE, the Samnites, an Italic people from the Abruzzo and Molise regions allied with Rome, conquered Pompeii, introducing their architectural styles and expanding the urban footprint. During the Samnite Wars (343–341 BCE) and the Latin War (340 BCE), Pompeii maintained loyalty to Rome, gradually adopting Roman customs and political affiliations.

Urban development during this period included the implementation of a more regular street grid influenced by Hippodamian planning principles. The city walls were reinforced in the early 3rd century BCE with limestone blocks forming a terrace wall that supported an earth embankment, enhancing defensive capabilities. After 290 BCE, Pompeii became a Roman socius, retaining linguistic and administrative autonomy while integrating into Rome’s political sphere. The city prospered through intensive agriculture, particularly wine and olive oil production, and engaged in trade with regions such as Provence and Spain, supported by expanded rural estates and workshops.

Roman Conquest and Republican Period (89 BCE–30 BCE)

During the Social Wars (91–88 BCE), Rome sought to consolidate control over its Italian allies, leading to the siege and capture of Pompeii by Sulla’s forces in 89 BCE. The Porta Ercolano gate sustained significant damage from ballista artillery, with impact craters still visible. Following surrender, Pompeii was established as a Roman colony under the name Colonia Cornelia Veneria Pompeianorum. Land grants were distributed to Sulla’s veterans, while opponents were dispossessed, marking a decisive shift in the city’s demographic and political composition.

Pompeii’s inhabitants were granted Roman citizenship and gradually assimilated culturally, adopting Latin as the primary language and Roman naming conventions. The city’s advantageous position on the Bay of Naples and fertile hinterland fostered economic prosperity. Pompeii became a key transit point for maritime goods, connected to Rome and southern Italy via the Appian Way. Public architecture flourished, with the construction or refurbishment of significant buildings such as the amphitheatre (circa 70 BCE), Forum Baths, and Odeon, reflecting the city’s elevated status within the Roman Republic.

Imperial Roman Period (30 BCE–79 CE)

Under Augustus and subsequent emperors, Pompeii experienced substantial urban development and infrastructural improvements. Notable public works included the Eumachia Building, serving as the wool market and fullers’ guild headquarters; the Sanctuary of Augustus; and the Macellum, a public market. The city’s water supply was enhanced by a branch of the Serino Aqueduct, constructed around 20 BCE by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, which supplied public baths, street fountains, and private residences.

Pompeii’s social and economic life was diverse, featuring entertainment venues such as two theatres and an amphitheatre renowned for its sophisticated crowd control design. The economy included at least 31 bakeries, numerous thermopolia (food stalls), wool processing workshops, and garum production facilities. Agriculture thrived on volcanic soils, producing grains, wine, olive oil, and various fruits. The city experienced a violent riot in 59 CE between Pompeians and Nucerians in the amphitheatre, resulting in a ten-year ban on such events imposed by the Roman Senate. A major earthquake in 62 CE caused extensive damage, prompting rebuilding efforts focused on private residences and public baths, including the construction of the architecturally advanced Central Baths. Emperor Nero and his wife Poppaea visited Pompeii around 64 CE, making offerings to the temple of Venus, the city’s patron deity.

Eruption of Mount Vesuvius and Destruction (79 CE)

On 24 August 79 CE, Mount Vesuvius erupted violently, burying Pompeii beneath 4 to 6 meters of volcanic ash and pumice. Recent research suggests the eruption may have occurred in autumn rather than summer. The eruption unfolded over two days, beginning with a pumice fall that allowed many inhabitants to flee. Subsequently, pyroclastic flows devastated the city, causing the deaths of those who remained. Archaeological excavations have uncovered approximately 1,150 bodies, many clutching valuables, indicating attempts to escape with possessions.

The city was covered by up to twelve layers of volcanic deposits, preserving buildings, frescoes, and organic materials in exceptional detail. Pliny the Younger’s eyewitness account describes the eruption and the death of his uncle, Pliny the Elder, who perished during a rescue attempt. Multidisciplinary studies confirm that intense heat from pyroclastic flows was the primary cause of death rather than suffocation.

Rediscovery and Excavation (16th century–Present)

Pompeii’s ruins were first encountered in 1592 during aqueduct construction, but systematic identification occurred in the late 17th century. Large-scale excavations began in 1748 under Spanish engineer Roque Joaquín de Alcubierre, with significant progress during the French occupation in the early 19th century. Giuseppe Fiorelli’s mid-19th-century reforms introduced scientific excavation methods, including division of the city into regions and insulae, house numbering, and the development of plaster casts to capture the forms of victims.

Excavations have revealed a wide range of structures, from modest homes to luxurious villas, as well as extensive graffiti illuminating social and political life. Modern archaeological practice emphasizes conservation and documentation, with projects such as the “Grande Progetto Pompei” initiated in 2012 to stabilize structures and prevent collapse. Recent discoveries include harnessed horses in the Villa of the Mysteries, a thermopolium with preserved food remains, a ceremonial chariot, and a painted tomb of a freed slave involved in cultural activities. Conservation challenges persist due to exposure and tourism, but ongoing efforts aim to preserve Pompeii’s unparalleled archaeological heritage.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Early Settlement and Pre-Roman Period (8th–5th century BCE)

During its early development, Pompeii was inhabited primarily by Oscan-speaking communities organized into five villages, later unified into a single settlement. The population exhibited a blend of indigenous Italic and emerging Greek cultural influences, as seen in religious practices centered on the cult of Apollo and the construction of Doric temples. Domestic architecture featured Tuscan-style atria, indicative of patriarchal family structures and social stratification, with landowning elites overseeing agricultural estates and artisans supporting local crafts.

The economy was based on mixed farming, exploiting fertile volcanic soils to cultivate grains, olives, and vines. The presence of a fortified tufa wall enclosing agricultural land reflects organized landholding and wealth accumulation. Archaeological evidence of workshops and early urban planning suggests small-scale craft production and local trade. Religious life integrated civic and spiritual functions through temples and household shrines, while the settlement’s location at crossroads facilitated exchange of goods and ideas.

Samnite Period (c. 450–290 BCE)

Under Samnite control, Pompeii experienced urban expansion and architectural transformation, adopting new building styles and a more regular street grid influenced by Hippodamian principles. The population remained predominantly Italic, with social hierarchies including landowners, artisans, and an emerging merchant class. Family units continued to dominate domestic life, with increased urbanization extending beyond the original settlement core.

Agricultural production intensified, focusing on wine and olive oil for local use and trade, supported by expanded rural estates. Urban workshops and markets diversified economic activities, including textile production and pottery. Religious practices combined Italic and Samnite traditions, with sanctuaries maintained and votive offerings reflecting community identity. Pompeii’s loyalty to Rome during regional conflicts enhanced its strategic and commercial role within Campania.

Roman Conquest and Republican Period (89 BCE–30 BCE)

The Roman conquest introduced significant demographic and cultural changes, with Roman settlers integrating alongside the native population. Roman citizenship was granted, and Latin became the dominant language, signaling cultural assimilation. Family structures adapted to Roman legal frameworks, with elite families adopting Roman naming conventions and participating in municipal governance, as attested by inscriptions naming magistrates such as duumviri.

Economic activities expanded, maintaining agriculture as a foundation while increasing maritime trade facilitated by Pompeii’s coastal position. The city became a hub for goods moving between Rome, southern Italy, and the Mediterranean. Public buildings such as the amphitheatre and baths reflected Roman social customs and leisure pursuits. Domestic interiors featured elaborate frescoes and mosaics, while shops and workshops thrived in urban neighborhoods. Religious life incorporated Roman deities alongside local cults, with public festivals and civic rituals reinforcing communal identity.

Imperial Roman Period (30 BCE–79 CE)

During the Imperial period, Pompeii flourished as a municipium with a sophisticated urban infrastructure. The population included Roman citizens of diverse origins, with social stratification evident in the contrast between wealthy villa owners and lower-class artisans and slaves. Family life remained patriarchal but showed increasing complexity, with freedmen participating in economic and religious activities. Civic officials managed public works and festivals, as documented in inscriptions.

The economy diversified, featuring numerous bakeries, thermopolia, wool processing workshops, and garum production facilities operating at household and industrial scales. Agriculture thrived on volcanic soils, producing staple crops and export commodities such as wine and olive oil. Domestic spaces were richly decorated with frescoes, mosaics, and architectural elements like atria and peristyles. Markets and fora supplied a wide range of goods, including imported spices and textiles. Transportation combined local carts, animal caravans, and maritime trade. Religious practices included worship of imperial cults and traditional Roman gods, with temples and household shrines integral to daily life. Cultural activities encompassed theatrical performances and public spectacles, though the 59 CE amphitheatre riot led to temporary restrictions. Education likely involved private tutors and public readings, reflecting Roman elite customs.

Eruption of Mount Vesuvius and Destruction (79 CE)

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius abruptly ended daily life in Pompeii. Archaeological evidence of food remains, household objects, and personal belongings preserved in situ reveals the final moments of the city’s inhabitants. The population comprised a range of social classes, from elite villa residents to common artisans and slaves, all affected by the disaster. Many attempted to flee with valuables, as indicated by bodies found clutching possessions.

The sudden burial preserved domestic interiors, public buildings, and religious sites in exceptional detail, offering unparalleled insight into urban life. The city’s infrastructure, including water supply and transportation networks, remained intact but unusable. Religious artifacts and graffiti attest to ongoing civic and social activities halted by the eruption. The event terminated Pompeii’s role as a vibrant municipium and regional center, freezing its last phase of daily life for posterity.

Rediscovery and Excavation (16th century–Present)

Although not a period of occupation, the rediscovery and excavation of Pompeii have profoundly shaped understanding of ancient daily life. Systematic archaeological methods revealed the city’s complex social fabric, economic specialization, and cultural practices. Plaster casts of victims provide unique evidence of family and social structures at the moment of death. Excavations uncovered a wide spectrum of domestic and commercial buildings, illuminating household layouts, decoration styles, and occupational diversity.

Graffiti and inscriptions have shed light on literacy, political life, and social relations. Conservation efforts continue to preserve Pompeii’s material culture, enabling ongoing study of its urban economy, religious customs, and civic organization. The site remains a benchmark for comparative studies of Roman municipal life in Campania and the broader Mediterranean world.

Remains

Architectural Features

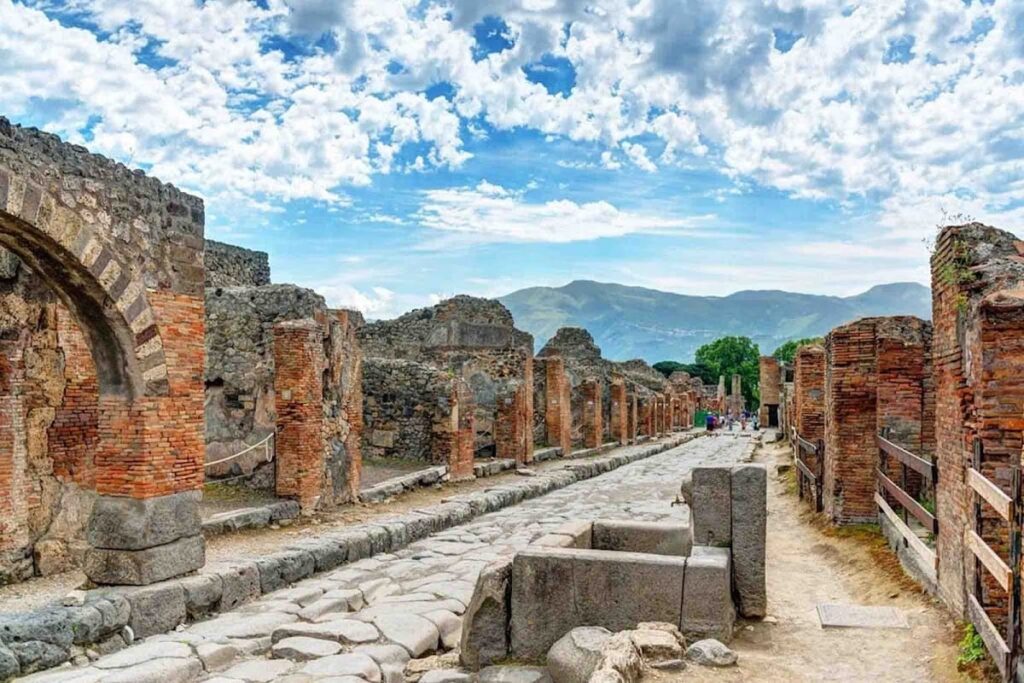

Pompeii’s urban area extends over approximately 44 to 67 hectares, situated on a coastal lava plateau about 40 meters above sea level. The city’s street network follows a grid pattern consistent with Hippodamian planning principles introduced during the Samnite period. Streets are paved with stone slabs and incorporate drainage systems, some of which survive in fragmentary form. The city was enclosed by defensive walls constructed and reinforced in multiple phases from the early 6th century BCE through the Roman period. These fortifications comprise tufa blocks, Sarno limestone orthostates, and rectangular limestone blocks supported by an earth embankment added in the early 3rd century BCE. Several gates punctuate the walls, notably the Porta Ercolano, which bears thousands of ballista shot craters from the 89 BCE siege.

Water supply was provided by a branch of the Serino Aqueduct, built around 20 BCE by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa. The system includes a well-preserved castellum aquae (water distribution basin) that regulated flow to public baths, over 25 street fountains, and private residences. Building materials include stone, brick, ashlar masonry, and Roman concrete (opus caementicium) in public structures. Urban expansion during the Augustan period saw the addition of new public buildings and infrastructure.

Key Buildings and Structures

Forum of Pompeii

The forum served as the city’s principal public space from the 2nd century BCE onward. It is bordered by major civic buildings, including the Capitolium, Basilica, and several temples. Before 80 BCE, the forum was enhanced with the colonnade of Popidius. Following the earthquake of 62 CE, many eastern forum buildings were restored and modified with marble veneers and architectural refinements. The paved open area and surrounding porticoes remain visible, with structural elements preserved.

Capitolium (Temple of Jupiter)

Situated adjacent to the forum, the Capitolium was constructed in the late 2nd century BCE and dedicated to Jupiter. The temple’s podium, cella (inner chamber), and frontal staircase survive partially. Built of stone and brick, it features a high podium and deep pronaos (porch). Some decorative elements and architectural details remain, though the superstructure is fragmentary.

Basilica of Pompeii

Located near the forum, the basilica dates to the 2nd century BCE and functioned as a judicial and administrative center. It has a rectangular plan with a central nave flanked by aisles separated by columns. Stone foundations, column bases, and portions of walls survive, while the roof structure is lost. The interior layout is discernible.

Amphitheatre of Pompeii

Constructed circa 70 BCE, the amphitheatre is among the oldest surviving Roman amphitheatres. It features elliptical seating arranged around an arena, with multiple entrances and exits designed for efficient crowd control. The complex includes a palaestra (gymnasium) and a central swimming pool (cella natatoria). Stone seating tiers and outer walls remain largely intact. Damage from the AD 59 riot is visible in some areas. Vaulted corridors and staircases survive in part.

Large Theatre and Odeon

Pompeii contains two theatres: a large open-air theatre built in the 2nd century BCE and a smaller odeon constructed in the 1st century CE. The large theatre’s semicircular seating (cavea) and stage building (scaenae frons) survive in fragmentary form. The odeon, used for musical performances and meetings, is a roofed structure with stone seating and remains of its stage area.

Eumachia Building

Constructed after the 62 CE earthquake, the Eumachia Building served as the wool market and headquarters of the fullers’ guild. Built entirely of brickwork, it contains numerous niches for statues, predominantly of imperial family members. The façade and interior walls survive, including a large entrance area. Near the entrance, a jar for collecting urine used in cloth processing was found. The building’s layout includes a large hall and adjoining rooms.

Macellum (Meat Market)

The macellum is a public market building dedicated to meat sales, dating to the late Republican or early Imperial period. Remains include a central courtyard surrounded by shops and stalls. Stone foundations and portions of walls survive, outlining the market’s plan.

Stabian Baths and Forum Baths

Pompeii’s public bath complexes include the Stabian Baths, constructed in the 2nd century BCE, and the Forum Baths, refurbished under Roman rule. Both contain typical bath features such as caldaria (hot rooms), tepidaria (warm rooms), frigidaria (cold rooms), and palaestrae (exercise yards). Hypocaust heating systems are preserved in parts. Walls, pools, and mosaic floors survive in varying conditions.

Thermopolia (Inns or Snack-bars)

Nearly 100 thermopolia operated in Pompeii, serving as food stalls. The thermopolium of Vetutius Placidus features a counter with several dolia (large terracotta jars) and a decorated lararium (household shrine) with frescoes of Lares, Mercury, and Dionysus. The thermopolium of Asellina has three sales counters, a lararium depicting Mercury and Bacchus, and bronze and terracotta furnishings. These structures retain counters, storage vessels, and wall paintings.

Fullonica of Stephanus

Originally a house converted into a workshop for fabric processing, the Fullonica of Stephanus contains large tanks on the lower floor used for washing clothes with water, soda, and urine. The upper floor was used for drying textiles. Stone basins, drainage channels, and work areas remain visible.

Garum Workshop

The garum workshop produced fermented fish sauce. Excavations uncovered sealed containers with sauce and a large deposit of amphorae in the adjacent garden area. The workshop’s stone foundations and storage facilities survive.

House of the Surgeon

Dating to the 2nd century BCE, the House of the Surgeon is an early atrium house with an inward-looking central courtyard. Stone walls, mosaic floors, and some frescoes remain. The layout includes reception rooms and service areas.

House of the Faun

Constructed in the 2nd century BCE and expanded in the 1st century BCE, the House of the Faun is a large, richly decorated mansion. It contains multiple atria, columned courtyards (peristyles), and extensive mosaic floors, including the renowned Alexander Mosaic. Walls, frescoes, and architectural elements survive extensively.

House of the Chaste Lovers

This large domus dates to the 1st century BCE and features richly decorated frescoes and mosaics. The house includes multiple rooms arranged around courtyards. Stone walls and decorative elements remain.

House of Julia Felix, House of the Golden Cupids, House of Loreius Tiburtinus, House of Cornelius Rufus, Garden of the Fugitives

These domus include gardens, orchards, and vineyards reconstructed based on frescoes and archaeological evidence. Structural remains include walls, garden layouts, and water features.

House of the Ship Europa, House of the Orchard, House of the Lovers, House of Leda and the Swan

These houses were reopened or newly excavated and restored in the 21st century. They preserve frescoes, mosaics, and architectural features such as atria and peristyles.

Villa of the Mysteries

Located just outside the city walls, this villa originated as a modest house in the 3rd century BCE and was expanded into a large residence. It is named for its well-preserved wall paintings depicting Dionysian initiation rites in the triclinium (dining room). In 2018, remains of harnessed horses were discovered in the villa’s stable area. The villa’s walls, frescoes, and structural elements survive extensively.

City Walls and Gates

The city walls were constructed and reinforced in multiple phases from the 6th century BCE through the Roman period. They incorporate tufa blocks, Sarno limestone slabs, and rectangular limestone blocks with an earth embankment. The Porta Ercolano gate bears thousands of ballista shot craters from the 89 BCE siege. The walls include a double parapet and a widened wall-walk added after the Second Punic War. Sections of the walls and gates remain standing, though some areas are fragmentary.

Infrastructure

Pompeii’s infrastructure includes the Serino Aqueduct branch supplying water to the city. The castellum aquae, a water distribution basin, is well preserved, showing channels and control mechanisms. Streets are paved with stone slabs and include drainage systems. Some street fountains and private water outlets survive. Remains of drainage channels and sewer systems are visible in parts of the city.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations have uncovered numerous artifacts spanning Pompeii’s history from the 8th century BCE to 79 CE. Pottery includes locally produced amphorae and tableware, as well as imported wares from Provence and Spain. Inscriptions found on walls and monuments include dedicatory formulas and political slogans, many in Vulgar Latin. Coins from various Roman emperors have been recovered, indicating economic activity and circulation.

Tools related to agriculture, textile production, and food processing have been found in workshops and domestic contexts. Domestic objects such as oil lamps, cooking vessels, and furniture fragments are common. Religious artifacts include statuettes, altars, and ritual vessels discovered in temples and shrines. Graffiti on walls provide personal messages and political statements. Organic remains, including wooden objects and foodstuffs, were preserved under volcanic ash.

Notable finds include erotic frescoes such as “Leda and the Swan” (discovered in 2018) and a painted tomb of Marcus Venerius Secundio, a freed slave and priest, found outside Porta Sarno in 2021. This tomb contains mummified remains and inscriptions referencing cultural events.

Preservation and Current Status

Pompeii’s preservation benefited from burial under volcanic ash, which protected buildings, frescoes, and organic materials. Many structures, including the amphitheatre, forum buildings, and private houses, remain well preserved, though some are partially collapsed or fragmentary. Restoration efforts have stabilized over 2.5 kilometers of ancient walls to prevent collapse. Some areas have undergone reconstruction using modern materials, while others are stabilized but left unrestored for conservation.

Environmental threats include weathering, erosion, and vegetation growth. Human impacts such as early excavation damage, tourism, vandalism, and World War II bombings have affected the site. The Schola Armatorum collapsed in 2010 due to heavy rainfall and poor drainage. Conservation projects, including the “Grande Progetto Pompei” initiated in 2012, focus on structural stabilization and preservation. Restoration approaches have shifted toward district-wide campaigns to achieve uniform conservation results.

Unexcavated Areas

Approximately one-third of Pompeii remains unexcavated. Some districts and structures are known from surface surveys and historic maps but have not been systematically explored. Geophysical studies suggest buried remains beneath modern developments and agricultural land. Future excavations are limited by conservation policies, funding, and the need to protect exposed areas. Ongoing research prioritizes documentation and targeted excavation to balance preservation with archaeological investigation.