Munigua: An Archaeological Site in Andalusia, Spain

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.6

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.juntadeandalucia.es

Country: Spain

Civilization: Roman

Remains: City

Context

The Archaeological Site of Munigua is located in Villanueva del Río y Minas, within the province of Seville, Andalusia, in southern Spain. It occupies a prominent hilltop plateau in the Sierra Norte de Sevilla, providing commanding views over the surrounding lowlands. This elevated position offered natural defensive advantages and influenced the site’s urban development.

Archaeological investigations have revealed a stratified occupation sequence beginning in the Iron Age, with evidence of pre-Roman Iberian settlement. The site’s landscape includes terraced slopes adapted for urban construction, reflecting the challenges of the rugged terrain. Munigua’s location within the mineral-rich Guadalquivir valley positioned it strategically for resource exploitation, particularly mining activities that shaped its economic and social history during the Roman period.

Systematic excavations initiated in the twentieth century have uncovered extensive urban remains, including public monuments, residential quarters, and funerary precincts. While many structures have been partially excavated and stabilized, significant portions remain buried beneath soil. The site is managed for both research and educational purposes, with interpretive materials facilitating public understanding of its archaeological significance.

History

Munigua’s archaeological record documents a prolonged human presence shaped by regional political, economic, and cultural transformations in southern Iberia. Initially occupied during the Iron Age by Iberian communities, the site evolved into a Roman municipium notable for its urban infrastructure and religious architecture linked to the exploitation of local mineral resources. Its peak occurred between the late 1st and 2nd centuries CE, followed by a gradual decline in late antiquity. The site later experienced an Islamic phase during the early medieval period before eventual abandonment.

Pre-Roman and Iberian Period (7th–1st century BCE)

Prior to Roman domination, Munigua was inhabited by Iberian groups from at least the 4th century BCE, as evidenced by ceramic assemblages recovered from the hilltop area. Although Punic ceramic fragments dating to the 7th century BCE have been found, these do not confirm a permanent settlement at that time but rather suggest early trade or cultural contacts. The main pre-Roman occupation consisted of a fortified Iberian settlement situated on the highest part of the hill, which was later cleared to accommodate Roman monumental constructions such as the Terrace Sanctuary.

This occupation fits within the broader context of Iberian culture in the Guadalquivir valley, characterized by small hilltop communities engaged in local resource exploitation and trade networks. Archaeological evidence indicates continuous habitation of the upper hill area from the 4th century BCE onward, laying the groundwork for subsequent Roman urbanization.

Roman Republican and Early Imperial Period (1st century BCE – 1st century CE)

During the late Roman Republic and early Empire, Munigua became increasingly integrated into the Roman provincial system, closely associated with regional mining activities, particularly copper and iron extraction. Mining operations are documented beneath areas that would later host public buildings and elite residences, indicating the economic foundation of the settlement. Architectural remains from the Augustan period attest to early urban development, though the majority of monumental construction occurred in the late 1st century CE.

In approximately 70 CE, under Emperor Vespasian, Munigua was granted Latin rights and elevated to the status of municipium, designated municipium Flavium Muniguense. This legal recognition coincided with a significant phase of urban expansion, including the erection of the Terrace Sanctuary, a monumental terraced complex built over earlier residential structures that were deliberately demolished. The sanctuary’s architectural design reflects Italic influences, resembling Republican sanctuaries such as Fortuna Primigenia at Praeneste and Hercules Victor at Tibur, and was likely dedicated to Fortuna and Hercules, though no dedicatory inscriptions survive.

Roman Imperial Peak (1st–2nd centuries CE)

Munigua attained its zenith during the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, benefiting from the exploitation of abundant local mineral deposits, including copper, iron, and gold. Archaeological evidence, such as extensive slag deposits, confirms large-scale mining operations that generated wealth supporting the construction of public amenities, including baths, a forum complex, and elite residences. The forum, situated on a terraced platform on the eastern slope, incorporated a basilica, curia (city council), and a sanctuary dedicated to Dis Pater, the deity associated with the underworld and mining activities.

Elite domestic architecture flourished near the forum, with large multi-room houses featuring specialized facilities such as oil presses and smelting ovens, reflecting a socially stratified urban population. The early 2nd century CE saw the addition of a marble-clad podium temple and a two-story portico, enhancing the city’s monumental character. Agricultural production, particularly olive oil and wine, supplemented the economy, supported by installations identified within the urban fabric. Munigua’s urban layout and religious institutions demonstrate its integration into Roman civic and cultic traditions, serving as a regional administrative and cultic center for surrounding mining settlements.

Late Roman Period and Decline (3rd–5th centuries CE)

The late 3rd century CE was marked by a significant earthquake that caused extensive damage to key structures, including residential buildings, the forum, and the two-story portico. This event initiated a period of urban contraction and decline. The city walls, constructed in the late 2nd century but never completed, fell into disrepair by the 3rd century. Concurrently, mining activities diminished, leading to a reduction of the inhabited area to approximately 4.5 hectares during the early 4th century.

Population shifts saw residents retreating from the lower town to the surrounding hills, although some urban functions persisted along the main north-south street (cardo maximus). The emergence of late Roman tabernae (shops) indicates a transition toward handicraft and small-scale commerce. Imported ceramics from this period demonstrate that Munigua maintained limited economic connections despite its reduced size. By the 5th century, parts of former residential zones were repurposed as necropolises, with burial evidence extending into the 7th century. The city’s abandonment was gradual, without evidence of violent destruction.

Early Medieval and Islamic Period (8th–12th centuries CE)

Following the Islamic conquest of the Iberian Peninsula in the early 8th century, Munigua experienced a phase of Islamic presence lasting until the 12th century. Archaeological finds include Arabic coins, Islamic pottery, and terracotta oil lamps. Graves conforming to Islamic burial customs have been excavated, characterized by bodies placed on their right side facing south. Some burials exhibit a syncretic blend of Islamic and local funerary traditions, including the presence of grave goods, which is atypical for orthodox Islamic interments.

The nature of this occupation remains uncertain, whether representing continuous settlement or intermittent strategic use. The site’s defensible hilltop location likely contributed to its role as a refuge or outpost during the political and religious transformations of Al-Andalus. After the 12th century, Munigua was abandoned and gradually fell into ruin.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Roman Republican and Early Imperial Period (1st century BCE – 1st century CE)

During its initial Romanization, Munigua’s population comprised indigenous Iberians and Roman settlers, forming a socially stratified community. Inscriptions attest to the presence of local magistrates, such as duumviri, reflecting the establishment of formal municipal governance following the grant of Latin rights under Vespasian. Economic life centered on copper and iron mining, with operations located beneath areas later occupied by public buildings and elite residences.

Agricultural production, including olive oil and wine, supplemented mining activities, supported by installations identified within the settlement. Residential architecture reveals large houses with multiple rooms and specialized facilities such as oil presses and smelting ovens, indicating wealth derived from mining and agriculture. Domestic interiors likely featured Roman-style decoration, although specific evidence at Munigua is limited. Markets and shops supplied both local and imported goods, with transport facilitated by mule caravans and footpaths connecting Munigua to broader Baetican trade networks. Religious life revolved around monumental cult complexes like the Terrace Sanctuary, dedicated to Fortuna and Hercules, integrating Italic religious traditions with local practices.

Roman Imperial Peak (1st–2nd centuries CE)

At its height, Munigua functioned as a municipium with a well-defined social hierarchy including elite landowners, magistrates, artisans, and laborers engaged in mining and agriculture. Inscriptions name prominent officials such as Lucius Valerius Firmus, who financed public buildings, underscoring the role of local elites in civic affairs. Domestic architecture featured peristyles, triclinia (dining rooms), and facilities for oil production and metalworking within elite houses.

Mining remained the economic foundation, with extensive slag deposits attesting to large-scale extraction of copper, iron, and gold. Agricultural production continued to sustain the population, evidenced by presses and amphora fragments. Craft workshops likely operated near the forum, supporting local needs and regional trade. Dietary remains suggest consumption of cereals, olives, fish, and possibly imported delicacies, consistent with a prosperous Roman town. Religious observance was prominent, with monumental structures such as the marble-clad podium temple and the sanctuary to Dis Pater reflecting the city’s spiritual and economic ties to mining. Public festivals and rituals likely reinforced communal identity and social cohesion.

Late Roman Period and Decline (3rd–5th centuries CE)

After the late 3rd-century earthquake, Munigua’s population declined and shifted toward the surrounding hills, reflecting reduced economic activity and insecurity. The social structure became less stratified, with evidence of small-scale commerce and handicrafts replacing large-scale mining. Archaeological remains indicate continued urban activity along the main street, where late Roman shops operated. Imported ceramics demonstrate ongoing, though diminished, trade connections.

Residential buildings show damage and partial abandonment, and the incomplete city walls fell into ruin, signaling weakened civic organization. Diet likely became more localized, focusing on subsistence agriculture. Religious practices adapted to changing circumstances; damaged sanctuaries remained focal points for limited worship. The conversion of former residential areas into necropolises in the 5th century reflects shifting land use and social customs, with burial practices continuing into the 7th century. Civic institutions likely dissolved or transformed as the city lost its municipal functions.

Early Medieval and Islamic Period (8th–12th centuries CE)

During the Islamic phase, Munigua’s population probably included Arab or Berber settlers and possibly converted locals, as indicated by Islamic burial customs. Some graves exhibit syncretism, blending Islamic and local traditions. Economic activities are less documented, but the site’s defensible position suggests a strategic role, possibly as a refuge or outpost rather than a fully functioning urban center. Agricultural production likely persisted on a small scale.

Material culture, including Arabic coins and pottery, indicates integration into Islamic economic and cultural networks in Andalusia. Daily life adapted to Islamic norms, including changes in dress, diet, and religious observance. The absence of large-scale public building projects suggests a community focused on survival and local administration. Munigua’s civic importance shifted from a Roman municipium to a minor strategic settlement within Al-Andalus. Its abandonment after the 12th century reflects broader regional political and demographic changes.

Remains

Architectural Features

Munigua’s archaeological remains reveal a complex urban settlement adapted to a hilltop plateau, with terraced construction accommodating the sloping terrain. Building materials include local stone, brick, and Roman concrete (opus caementicium). The urban fabric comprises civic, religious, and residential structures, many dating to the 1st and 2nd centuries CE. Defensive walls initiated in the late 2nd century CE were never completed and fell into ruin by the 3rd century. The contraction of the settlement in late antiquity led to the repurposing of some areas for burial use. Preservation varies from substantial masonry to foundations and partial walls, reflecting a range of construction techniques and phases.

Key Buildings and Structures

Terrace Sanctuary (Terrassenheiligtum)

Constructed circa 70 CE during the early Flavian period, the Terrace Sanctuary occupies a rectangular area approximately 35.2 by 54.5 meters on Munigua’s western side. It is arranged on three superimposed platforms, with the rear western platform featuring a stepped retaining wall nearly nine meters high, exceptionally well preserved. The sanctuary’s courtyard contains a nearly square cella positioned laterally, alongside a ring sunk into the floor and two rectangular basins of uncertain function, possibly for floral displays. The sanctuary was built over earlier residential buildings that were deliberately leveled. Walls up to six meters high remain visible despite burial under debris. The sanctuary lost its cultic function and was profaned by the 7th century CE.

Podium Temple (Podiumstempel)

Located between the forum and the Terrace Sanctuary, the Podium Temple dates to the 2nd century CE, constructed shortly after the sanctuary. It was partially built over older walls and originally featured four front columns. Masonry includes clamp holes indicating marble cladding. The temple’s south-southeast orientation differs from the sanctuary’s alignment, though their proximity suggests a relationship. The temple’s dedication remains unknown. Surviving remains include substantial wall fragments and column bases.

Forum

The forum is situated on the lower slope of the city hill, built on a terraced artificial platform supported by a retaining wall approximately five meters high and 1.2 meters thick on the east side. Although wall collapse and earth pressure obscure the original ground plan, a central area with a portico enclosing a small square is identifiable. Two construction phases are evident: an older phase with a portico built from well-mortared and dry-set rubble stones, and a younger southern addition connected by a yellow brick pillar. Beneath the forum lie remains of an earlier thermal complex dated to the Flavian period by coins and ceramics. Numerous statue bases indicate rich decoration. A northern room with a heavy block foundation is interpreted as the base for an equestrian statue dedicated to Dis Pater. Inscriptions record that L. Valerius Firmus, twice duumvir, donated the temple, forum, portico, exedra, and tabularium. The forum and an adjacent house were likely destroyed suddenly by a late 3rd-century earthquake, supported by the discovery of a body beneath collapsed debris.

Two-Story Hall (Doppelgeschossige Halle)

Excavated between 1960 and 1966, this hall lies on the slope adjoining the west side of the forum, opening onto a small open space predating both structures. Dating ranges from the early imperial to Hadrianic periods. The hall measures 14.20 meters in length, with widths of 3.22 meters (south side) and 3.45 meters (north side). Its back wall, north side wall, and some pillars rest directly on bedrock. The floor consists of dark stone chippings mixed with lime mortar laid over the rock. Three southern pillars have square recesses in the bedrock interpreted as bases for portrait statues of emperors. The hall collapsed at the end of the 3rd century and was later reused with smaller rooms inserted within the ruins.

Aedicula

This small shrine, possibly dedicated to Mercury, dates variably from the mid to late 1st century CE or early 2nd century CE. Constructed from sandstone and sandstone conglomerate, its architectural elements resemble column bases found on the west side of the forum, suggesting contemporaneous construction. One column closely matches those from the forum. The aedicula’s remains include partial walls and column fragments.

Baths (Thermen)

Located in the northeast sector of Munigua, the baths are relatively small, with surviving walls reaching about four meters in height. Constructed primarily of red brick reinforced with mortar and corner piers, preservation varies from well-preserved sections to nearly dismantled areas. The complex includes a frigidarium (cold room), apodyterium (changing room), a nymphaeum with a water cascade fed by a lead pipe, and a caldarium (hot room) with a visible hypocaust heating system. A water well was added north of the frigidarium in later phases. The baths underwent several renovations during the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE. Underneath the baths are remains of iron production facilities active until the mid-1st century CE. Wall paintings and sculptures have been found, including a large draped statue possibly associated with the forum. Luxurious features include a marble Eros sarcophagus and three inscribed bases decorated with pearl bars and vine motifs.

House 1 (Haus 1)

Discovered in 1967, House 1 is a private residence initially constructed in the early 1st century CE with foundations of opus caementicium and brick walls. Construction techniques evolved through phases, including opus testaceum and later opus mixtum. The first phase includes evidence of an oil press and several smelting furnaces, though these may not have been contemporaneous. The second phase, dating from the late 1st to 2nd century CE, corresponds to the main urban development. The house contains 22 rooms arranged around a central elongated complex comprising a vestibule, peristyle, and triclinium (dining room). The entrance is slightly offset along the longitudinal axis, and the front room facing the street was open at ground level, likely serving as a porch.

House 2 (Haus 2)

Located in the northern part of the settlement adjacent to the forum, House 2 is accessible via a narrow ramp. It includes a room with columns interpreted as a cellar for an upper floor. The northwest room functioned as a workshop with an oil press, while the adjacent southern room served as a shop with street access. The central room was used for business and storage. Other rooms likely served as living and commercial spaces, with a possible stair ramp leading to the upper floor. The site was used in at least two earlier settlement phases, initially possibly for a press and later for iron production with several furnaces. The first building phase dates to the mid-1st century CE at the earliest; the second main phase dates to 100–150 CE. The second phase collapsed in the late 3rd century due to an earthquake and was partially restored in the early 4th century. A final phase from the 5th to 7th centuries marks the end of the building’s use, though the surrounding area remained inhabited until the Reconquista.

House 6 (Haus 6)

House 6 is an annex to House 1, architecturally similar and initially difficult to distinguish. From the second phase onward, it functioned as a separate residence with 22 rooms arranged similarly to House 1. It was likely constructed shortly after House 1, as indicated by the dividing wall between the two buildings.

City Walls (Stadtmauer)

Constructed in the last third of the 2nd century CE, the city walls were never completed, leaving the western side open. The wall’s course follows the boundaries of the southern and eastern necropolises, incorporating parts of these burial areas within the city limits. Excavations have revealed the southern gate and four towers spaced approximately 50 meters apart. By the 3rd century CE, the walls were already in a state of ruin.

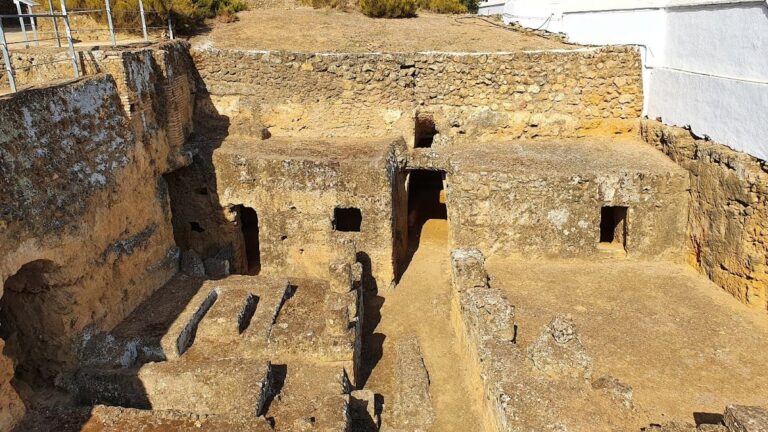

Necropolises

Two main necropolises, located to the south and east of the settlement, were used regularly from the 1st to 4th centuries CE. Both inhumation (supine position) and cremation burials were practiced, with grave goods accompanying many interments. Cremations involved either burning on-site (bustum) or burning in a separate pyre (ustrina) with subsequent burial of ashes. Four types of burial installations have been identified: unprotected grave pits, urn or container burials, bustum, and ustrina waste pits. Grave goods vary by gender and age, including jewelry and toiletry items for women, weapons and tools for men, and toys and amulets for children. Coins are rare in graves and absent in urn burials, while beads are common in children’s and female graves. The necropolis was enclosed by a wall, defining a funerary precinct.

Islamic Graves

Excavated in 1998, Islamic graves date roughly from the late 7th to 9th centuries CE. The burials follow Islamic customs, with bodies laid on the right side, head tilted back facing south, and arms extended alongside the body. Some graves contain small grave goods, indicating a syncretic burial practice blending Islamic and local traditions. Associated ceramic finds date from the 8th/9th to 12th centuries CE. The nature of this Islamic presence—whether continuous settlement or temporary strategic occupation—remains unclear.

Other Remains

Surface traces and architectural fragments indicate additional buildings and structures, including older Iberian settlements beneath the Terrace Sanctuary. Remains of iron production facilities have been found beneath the baths. Seven houses with upper stories have been identified, some with commercial functions on the ground floor. Numerous ceramic, glass, and metal artifacts attest to ongoing craft and trade activities throughout the site.

Preservation and Current Status

The Terrace Sanctuary retains well-preserved walls up to nine meters high on its western side, with other walls visible up to six meters. The forum’s retaining wall and portico remain partially standing, though much of the structure has collapsed. The Podium Temple survives as substantial wall fragments and column bases. The baths vary in preservation, with some walls intact and others dismantled. Residential houses retain foundations and partial walls, with some internal room divisions visible. The city walls are fragmentary, with towers and gates partially excavated but largely ruined. Necropolises are preserved as burial pits and associated grave goods. Islamic graves are excavated but remain fragmentary. Many structures have undergone consolidation but not full restoration, with some areas stabilized in situ. Excavations and conservation efforts have been ongoing since the mid-20th century.

Unexcavated Areas

Several sectors of Munigua remain covered by soil and unexcavated. Surface surveys and geophysical studies conducted in the early 2000s suggest buried remains beneath these areas, including possible additional residential and industrial buildings. The older Iberian settlement beneath the Terrace Sanctuary is partially explored but not fully excavated. No detailed plans for future excavations have been publicly documented, and some areas are preserved to protect fragile remains.