Miletus: An Ancient Ionian City on the Aegean Coast of Turkey

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.6

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: muze.gov.tr

Country: Turkey

Civilization: Byzantine, Greek, Roman

Remains: City

Context

Miletus is located near the modern town of Didim in Aydın Province, western Turkey, positioned on the lower floodplain of the Büyük Menderes River (ancient Maeander) close to the Aegean coastline. In antiquity, the city faced a coastal inlet and the river’s mouth, providing direct maritime access, unlike the present-day inland plain formed by extensive sedimentation.

Geomorphological and archaeological investigations have demonstrated that the Maeander River’s delta progressively advanced seaward over millennia, significantly altering the coastline and transforming the original harbor environment. The site occupies a peninsula formed by alluvial deposits, which once comprised a series of islands inhabited since the Neolithic period.

Archaeological stratigraphy reveals continuous occupation from the Neolithic through the Bronze Age, with material culture indicating early settlement phases. Some scholars associate Miletus with the Late Bronze Age toponym “Millawanda” or “Milawata” found in Hittite texts, though this identification remains debated.

During the Archaic period, Miletus emerged as a prominent Ionian polis, establishing a network of overseas colonies documented in literary and epigraphic sources. The city’s historical trajectory includes its capture by Persian forces in 494 BCE during the Ionian Revolt, followed by phases of Hellenistic and Roman rebuilding. Byzantine occupation persisted despite environmental challenges, notably the gradual silting of the harbor, which diminished its maritime significance.

Extensive archaeological remains survive across the site, encompassing civic, religious, and military structures. Systematic excavations began with German-led campaigns under Theodor Wiegand around 1899 and have continued under Turkish and international teams. Artifacts recovered are housed in regional museums and abroad, while ongoing research integrates fieldwork and geomorphological studies to refine understanding of Miletus’s long occupational history and environmental transformation.

History

Miletus, situated at the mouth of the Maeander River on the Aegean coast, developed through a succession of cultural and political phases shaped by its strategic location and fertile hinterland. From its earliest Neolithic settlements, the site evolved into a major Ionian city-state, playing a pivotal role in regional trade, colonization, and cultural exchange. Over time, Miletus experienced shifts in sovereignty, including Persian, Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine rule, each leaving discernible impacts on its urban development and administrative status. Environmental changes, particularly the progressive silting of its harbor, critically influenced its economic fortunes and eventual decline.

Neolithic and Bronze Age

Archaeological data indicate that Miletus was first occupied during the Neolithic period (circa 3500–3000 BCE) on islands near the Maeander River’s mouth, which later coalesced into the Miletus peninsula. By the 4th millennium BCE, a centralized settlement had formed, traditionally linked in mythology to the Leleges people. Material culture from the Late Bronze Age reveals Mycenaean influence, with the city identified in Hittite records as “Millawanda” or “Milawata.” Linear B tablets attest to a Mycenaean administrative presence, including a governor under the Ahhiyawa polity (Mycenaean Greece). The city was fortified according to Hittite military plans and endured raids amid regional conflicts. The Late Bronze Age collapse around 1200 BCE, likely involving incursions by the Sea Peoples, resulted in the destruction of Miletus’s Mycenaean phase.

Greek Dark Ages and Ionian Foundation

Following the Bronze Age collapse, Ionian Greeks from mainland Greece, led by Neleus—son of the last Athenian king Codrus—seized Miletus around 1050 BCE. This conquest involved the killing of the male indigenous population and the integration of local Carian women, establishing a new Ionian identity. This migration was extensive enough to lend the name Ionia to the entire coastal region. Miletus became the foremost Ionian city, founding colonies such as Cyzicus (756 BCE) and Sinope (751 BCE). It was a founding member and leader of the Ionian League, initially comprising seven city-states and later expanding to twenty-five, including some non-Ionian communities.

Archaic Period and Tyranny

During the Archaic period, Miletus expanded into the wealthiest and most powerful Ionian polis, establishing a maritime empire with up to 80–90 colonies across the Black Sea and Mediterranean. Internal social tensions between aristocrats and common citizens led to the abolition of monarchy following the assassination of King Leodamas in the 7th century BCE. The tyrant Thrasybulus preserved Miletus’s independence during a twelve-year conflict with Lydia, allying with Corinth. Subsequently, under the tyrant Phrysibulus (from 616 BCE), the city promoted social stability, expanded trade and colonization, minted its own coinage, and invested in urban fortifications. Miletus comprised an inner and outer city, both fortified and protected by four harbors shielded by the island of Lade. Despite ongoing military conflicts with Lydia (612–600 BCE), Miletus maintained naval supremacy and avoided conquest.

Ionian Revolt and Persian Rule

Following Phrysibulus’s death, tyrannies continued under Foantus and Damasenor, who governed with the support of wealthy landowners and shipowners, exacerbating social divisions between oligarchs (“plutis”) and laborers (“chairomachoi”). Around 547 BCE, Miletus voluntarily submitted to Cyrus the Great of Persia, initially retaining internal autonomy. Persian-appointed tyrants, including Histiaeus and Aristagoras, administered the city. Aristagoras instigated the Ionian Revolt (499–494 BCE) against Persian domination, achieving early successes such as the capture and burning of Sardis and a naval victory near Cyprus. However, the revolt culminated in defeat at the Battle of Lade (494 BCE). Subsequently, Persian forces besieged and destroyed Miletus, killing the male population, enslaving women and children, and deporting survivors to Babylon and the Persian Gulf region, effectively terminating the city’s independence and regional influence.

Classical Period and Reconstruction

After the Persian defeat at Plataea in 479 BCE, Miletus was liberated and underwent extensive reconstruction under the urban planner Hippodamus, who implemented the city’s characteristic grid plan. The city joined the Delian League under Athenian leadership, paying tribute from the mid-5th century BCE. Political struggles ensued, with oscillations between oligarchic and democratic governance; Athens intervened to support oligarchs against popular uprisings. During the Peloponnesian War, Miletus initially allied with Athens but revolted in 412 BCE, permitting a Persian garrison and maintaining democracy under Persian satrap Tissaphernes. Spartan general Lysander imposed oligarchic decarchies around 405 BCE, suppressing democratic factions. By the early 4th century BCE, moderate democracy was restored through external mediation. Miletus remained under Persian suzerainty, incorporated into the Carian kingdom governed by the Hecatomnid dynasty without significant disruption to its internal order.

Hellenistic Period

Miletus resisted Alexander the Great’s siege in 334 BCE but surrendered without major destruction. Alexander established a democratic government and appointed a local ruler, Stephanephorus. After Alexander’s death, the city passed through the control of various Diadochi, including Antigonus I, Demetrius Poliorcetes, Lysimachus, and the Seleucids, who restored democratic constitutions under royal oversight. The city was contested between the Seleucid and Ptolemaic kingdoms; Ptolemy II Philadelphus captured it in 279 BCE and supported local tyrants such as Timarchus. Miletus engaged in regional conflicts, aligning with Rhodes and opposing Macedonian kings during this period of political turbulence.

Roman Period

Miletus allied with Rome during the Roman–Syrian War (192–188 BCE) and was incorporated into the Roman province of Asia after 133 BCE. While retaining some municipal autonomy, the city’s political prominence declined relative to neighboring centers like Ephesus and Pergamon. Territorial expansion occurred through synoecism with nearby cities such as Pidasa and Myus during the late Hellenistic and early Roman periods. The city’s freedom fluctuated during the Mithridatic Wars but was restored by Marcus Antonius in 38 BCE. Apostle Paul’s visit around 57 CE attests to an established Christian community. Under Roman rule, Miletus experienced urban development, including new fortifications constructed in 262 CE and monumental public buildings such as baths, theaters, and agoras. However, sedimentation from the Maeander River progressively silted the harbor, diminishing Miletus’s maritime role and economic vitality.

Byzantine Period and Later History

During the Byzantine era, Miletus functioned as an archbishopric and later a metropolitan bishopric. A small fortress known as Palation was constructed near the city, reflecting defensive priorities amid regional instability. The urban area contracted significantly, with much of the ancient city abandoned or repurposed. The Seljuk Turks captured Miletus in the 14th century, utilizing it as a trading port with Venice. Under Ottoman rule, the city continued as a harbor until silting rendered it unusable, leading to abandonment. Today, the ruins lie several kilometers inland due to sediment accumulation and environmental degradation caused by deforestation and overgrazing. The Ilyas Bey Complex, including a mosque built in 1403, remains a notable heritage site from the late medieval period.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Classical Period and Reconstruction

Following the Persian destruction and subsequent liberation in 479 BCE, Miletus underwent comprehensive urban redevelopment based on Hippodamus’s grid plan, reflecting renewed civic organization. The population was predominantly Ionian Greek, structured into social strata including aristocratic landowners, merchants, artisans, and laborers. Epigraphic evidence attests to civic officials such as magistrates and members of the boule, indicating active political institutions within the polis framework.

Economic life centered on maritime trade, craftsmanship, and agriculture. The city’s four harbors facilitated extensive commerce connecting Miletus to the Aegean and Black Sea regions. Archaeological findings reveal workshops producing textiles, pottery, and luxury goods at both household and industrial scales. Domestic architecture included mosaic floors and painted walls, suggesting a degree of wealth and aesthetic refinement. Dietary remains indicate consumption of locally produced cereals, olives, fish, and imported luxury items, reflecting a mixed subsistence and trade-based economy.

The agora served as a marketplace and political assembly space, where citizens engaged in commercial exchange and governance. Transportation relied on sea vessels for long-distance trade and carts or pack animals for inland movement. Religious life centered on cults of Apollo, Athena, and Poseidon, with the Didyma sanctuary functioning as a major pilgrimage site. Festivals and oracular consultations played integral roles in social cohesion. Miletus held a prominent position within the Delian League, paying tribute to Athens and participating in regional alliances, underscoring its status as a leading Ionian polis.

Hellenistic Period

Under Macedonian and subsequent Hellenistic rule, Miletus maintained its Ionian Greek cultural identity while adapting to new political authorities. The population remained largely Greek, with local elites collaborating with Hellenistic rulers. Civic institutions persisted under royal supervision, with democratic constitutions restored but subject to external influence. Inscriptions document local magistrates and benefactors, indicating continuity in municipal governance.

Economic activities continued to emphasize maritime commerce, though political instability affected trade networks. The city supported artisans, merchants, and administrators, with evidence of coin minting and expanded urban infrastructure. Residential quarters featured mosaic decorations and well-planned street grids consistent with Hippodamian principles. Dietary and domestic practices showed continuity with the Classical period, supplemented by imported goods from Ptolemaic and Seleucid territories.

Markets and agoras remained focal points for economic and social interaction, while harbors facilitated regional connectivity. Religious practices included traditional Ionian cults alongside the introduction of Hellenistic deities and royal cults. Miletus’s strategic location made it a contested prize among successor kingdoms, yet it retained a degree of autonomy as a polis within the shifting Hellenistic landscape.

Roman Period

During Roman provincial administration, Miletus transitioned from a dominant regional power to a municipium integrated within the province of Asia. The population comprised Roman settlers, local Greeks, and possibly other ethnic groups, as suggested by funerary inscriptions and civic titles. Social stratification included senatorial and equestrian elites, merchants, artisans, and slaves. Civic officials such as duumviri and aediles managed municipal affairs.

Economic activities diversified, encompassing agriculture, maritime trade, and manufacturing. Archaeological remains attest to olive oil production, textile workshops, and pottery kilns operating at industrial scales. The city’s diet incorporated bread, olives, fish, and imported delicacies, as evidenced by ceramic and faunal assemblages. Domestic interiors often featured mosaic floors and painted walls, while public amenities expanded to include baths, theaters, and aqueducts.

The agora and fora functioned as commercial and administrative centers, with goods ranging from local produce to luxury imports available in markets. Transportation combined riverine and maritime vessels with road networks connecting Miletus to inland Asia Minor. Religious life diversified, encompassing traditional Greek cults, imperial cult worship, and an established Christian community by the mid-1st century CE, as attested by Apostle Paul’s visit. Although harbor silting reduced maritime prominence, Miletus remained a significant provincial urban center.

Byzantine Period and Later History

In the Byzantine era, Miletus’s population contracted and urban complexity diminished, reflecting broader regional transformations. The city became an ecclesiastical center, serving as an archbishopric and later metropolitan bishopric, with clerical elites assuming prominent civic roles. The construction of the Palation fortress indicates a defensive focus amid political instability.

Economic activities scaled down, centering on sustaining the reduced urban population and supporting ecclesiastical functions. Archaeological evidence suggests repurposing of ancient buildings and limited new construction. Diet and domestic life adapted to a smaller, less affluent community, with local markets supplying essential goods. Transportation relied increasingly on land routes and limited coastal traffic.

Religious life was dominated by Christianity, with churches and monastic establishments replacing earlier pagan cults. Social customs aligned with Byzantine ecclesiastical traditions and imperial administration. Following Seljuk conquest in the 14th century, Miletus functioned as a trading port under Turkish and Venetian influence, though silting progressively isolated it from the sea. Under Ottoman rule, the city’s harbor use declined until abandonment, with the Ilyas Bey Complex standing as a late medieval architectural testament. Miletus’s civic role shifted from a major polis to a minor ecclesiastical and commercial site before eventual desertion.

Remains

Architectural Features

The archaeological remains of Miletus extend across the peninsula formed by sedimentation near the Maeander River’s mouth. The city’s layout evolved over centuries, with surviving structures predominantly civic, religious, and military. Construction techniques include finely cut ashlar masonry and large stone blocks, with Roman concrete (opus caementicium) employed in later phases. The urban fabric contracted notably during the Byzantine period, with fortifications enclosing smaller areas than in earlier times. The site preserves extensive public buildings, fortification walls, harbors, and sanctuaries, spanning from the Late Bronze Age through Late Antiquity. Due to delta progradation, ancient harbor areas now lie inland.

City walls are among the most prominent features, exhibiting multiple construction phases from the Late Bronze Age through Byzantine times. The acropolis was located on Kalabaktepe hill, fortified from the Geometric period but abandoned by the 1st century BCE. The urban center includes several agoras, temples, baths, gymnasia, and entertainment venues, many retaining well-preserved architectural elements. Harbors, once active on the coast, are now inland. Excavations have revealed a complex network of public spaces and infrastructure, with some areas only partially excavated.

Key Buildings and Structures

City Walls and Gates

The earliest city walls date to the Late Bronze Age (circa 1350–1050 BCE), with remains near the Theater Harbor. Archaic walls were constructed around 650 BCE and renovated circa 550 BCE, possibly enclosing the entire peninsula including Kalabaktepe hill. Following the city’s post-Persian reconstruction, new walls were built between 411 and 402 BCE, enclosing a similar area. Around 200–190 BCE, a southern city wall approximately 500 meters long was erected across the peninsula’s base, featuring towers spaced about 60 meters apart. These fortifications reached thicknesses of 4–5 meters and heights up to 9.5 meters. The walls were restored in 263 CE during Gothic invasions.

In 538 CE, Emperor Justinian commissioned smaller walls enclosing the northern peninsula, covering areas such as Humeitepe, Kaleteppe, and Lion Harbor. During the Byzantine period (9th–10th centuries CE), a fortress was constructed on Theater Hill (Kaleteppe), with settlement contracting around it. The main city gate, known as the Sacred Gate or Holy Gate, was located on the southern wall. Originally about 5 meters wide and flanked by two towers, it was rebuilt around 200–190 BCE and underwent its last major phase around 100 CE.

Akropolis

Kalabaktepe hill, rising 57 meters, served as Miletus’s acropolis from the Geometric period onward. It was fortified with walls and rebuilt during the city’s post-Persian reconstruction. However, by about 100 BCE, the acropolis was abandoned as it fell outside the new city walls. The nearby Kaleteppe (Theater Hill, 28 meters high) has been proposed as a secondary acropolis, but archaeological evidence for this is lacking.

Agoras

The Northern Agora, near Lion Harbor at the peninsula’s center, is the oldest agora in Miletus. It is a rectangular space measuring approximately 50 by 87.5 meters, surrounded by two L-shaped, single-aisled stoas with Doric columns, constructed in two main phases during the late Classical and Hellenistic periods (circa 350–160 BCE). A small Ionic prostylos temple stands centrally on the western side. Originally open on the east, the agora was later enclosed by a wall and shops.

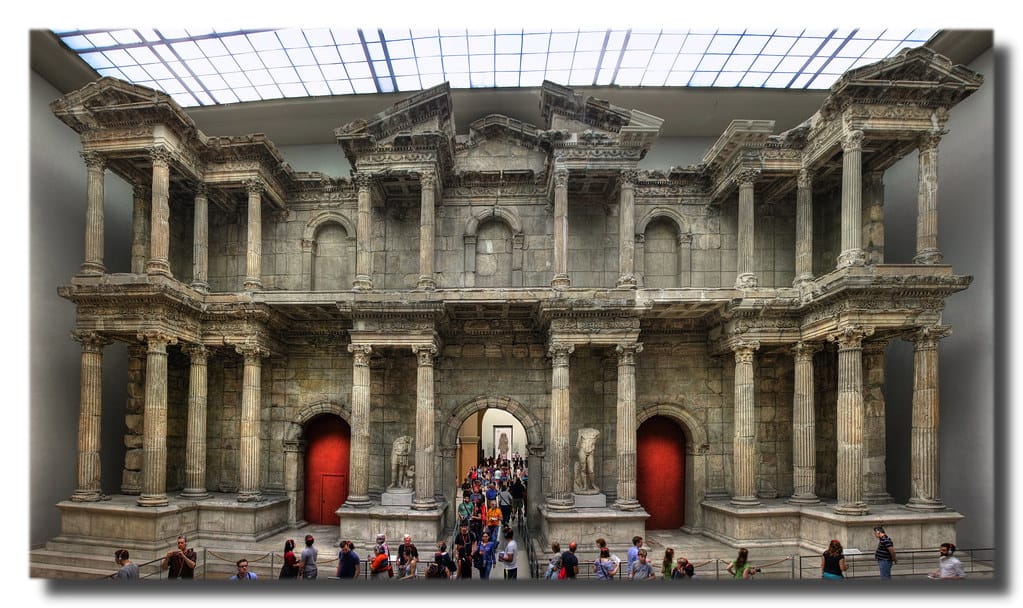

The Southern Agora, located south of the Northern Agora, was built in phases during the Hellenistic period (circa 280–150 BCE). It is one of the largest Greek agoras, measuring about 164 by 194 meters. Its northern gate, the Miletus Gate or South Agora Gate, was constructed around 120 CE. This two-story gate is approximately 29 meters long and 17 meters high, with Composite columns on the lower floor and Corinthian on the upper. The gate features three arched vaulted entrances on the lower level. The eastern side includes the East Stoa, about 189 meters long, while the north, west, and south sides have L-shaped stoas. The agora also contains a southern gate.

The Western Agora, built in the 2nd century BCE, lies south of the Theater Harbor and north of the Temple of Athena. It measures roughly 191 by 79 meters and is the youngest of the city’s agoras.

Temple of Athena

Located near the earliest settlement area south of the Theater Harbor, the Temple of Athena occupies a site with sanctuary use dating back to Mycenaean and Archaic periods. The Classical period temple, constructed after 479 BCE, is Ionic and unusually oriented north-south. It measures approximately 17.2 by 28.2 meters and features a pseudodipteral colonnade with 8 by 14 columns. The pronaos (front porch) has a true dipteral colonnade. The interior includes a pronaos and a naos (cella or main chamber).

Delphinion (Apollon Delfinion Sanctuary)

Situated near Lion Harbor, the Delphinion is associated with the cult of Apollo at Didyma and served as the starting point of the Sacred Way, an 18-kilometer procession route. The earliest remains date after 479 BCE, with the surviving building phase from around 340–320 BCE. The sanctuary originally had a Doric peristyle courtyard expanded to 50 by 60 meters from a smaller earlier size. It is surrounded on three sides (north, east, south) by stoas. The entrance is on the west side, later enhanced with a stoa. In Roman times, a monopteros (circular colonnade) was added centrally. Late Antique renovations included a propylon entrance.

Serapeion

The Serapeion, dedicated to Zeus Serapis and associated with Helios, is located west of the Southern Agora. Built in the 3rd century CE, it consists of a pronaos and naos. The pronaos is a tetrastyle prostylos portico with Composite columns. The naos measures about 22.5 by 12.5 meters and contains two rows of Ionic columns. Nearby remains possibly belong to a separate temple dedicated to Isis.

Kalabaktepe Temple

This Ionic temple on Kalabaktepe hill was constructed around 525 BCE. It measures approximately 6.8 by 8.7 meters.

Poseidon Altar

Located on the Poseidon promontory about 7 kilometers southwest of Didyma, this rectangular altar complex dates to around 575 BCE. It consists of an altar terrace measuring 11.1 by 9.5 meters and a sacrificial altar on the east side measuring 1.8 by 3 meters.

Buleuterion

The Buleuterion, or council house, is situated between the Northern and Southern Agoras. Constructed around 175–164 BCE, it likely replaced an earlier building. The complex includes a peristyle courtyard accessed via a propylon gate. The entire structure measures about 34.8 by 55.9 meters, with the main assembly hall approximately 34.8 by 24.3 meters. The hall features a theater-like auditorium with seating capacity for roughly 1,200–1,500 people. Architectural styles include Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian elements. A large altar was added to the courtyard during the Roman period.

Theater

The theater is built on the southern slope of Theater Hill (Kaleteppe). It served for theatrical performances, the citizens’ assembly (ekklesia), and possibly council meetings before the Buleuterion’s construction. The theater was rebuilt multiple times, with Hellenistic phases dating from 300 to 133 BCE. The surviving remains correspond to the final Roman phase. The theater is about 140 meters wide with 60 rows of seats. Seating is divided into three horizontal sections separated by passageways, and vertical aisles divide these sections into wedge-shaped sectors. The stage building (skene) is 40 meters wide, originally two stories, later three stories in the Roman period. Seating capacity is estimated at about 15,000 spectators, making it one of the largest theaters in Asia Minor during Roman times.

Stadium

The stadium is located on the western part of the peninsula, south of the Theater Harbor. Probably built by Eumenes II around 166 BCE, it measures approximately 192.3 meters long and 29.6 meters wide, comparable to the Olympic stadium. Some remains of starting gates for footraces have been found. The western end connects to the Eumenes Gymnasium via a propylon entrance.

Gymnasia

The Eumenes II Gymnasium lies between the Western Agora and the Stadium, near the Temple of Athena. Built by Eumenes II, it is architecturally aligned with the stadium and connected to it by a propylon entrance. The Eudemus Gymnasium, constructed around 200–150 BCE, is located in the city center east of the Northern Agora. Its south entrance features a propylon colonnade. The central courtyard (palaestra) measures 19 by 35 meters and is surrounded by Doric columns. The north side contains a row of rooms, including the ephebeion, a schoolroom for young men.

Baths

The Faustina Baths, near the Theater Harbor south of the theater and north of the stadium, were built in the 2nd century CE and named after Empress Faustina. The western part includes a palaistra (exercise area) measuring about 62 by 64 meters, connected to the stadium. The main bath building is basilica-shaped, approximately 80 meters long on the east side of the palaistra. It contains typical Roman bath rooms such as the tepidarium (warm room), frigidarium (cold room), caldarium (hot room), and sudatorium (steam room). A “Room of the Muses” dedicated to the imperial cult is also present.

The Capito Baths, located between the Delphinion and Eudemus Gymnasium east of the Northern Agora, possibly date to about 41–54 CE, making them the earliest Roman baths in Miletus. The complex measures approximately 96 by 40 meters. The western part includes a palaistra about 39 by 40 meters, while the eastern part contains a three-aisled main bath building.

Harbors

The Theater Harbor lies on the western coast of the peninsula, south of the theater. It was in use from prehistoric times through Late Antiquity. Archaeological investigations have focused on its southern part. Nearby are the theater, Eumenes II’s stadium and gymnasium, and the Western Agora.

The Lion Harbor, situated between Humeitepe and Theater Hill, extends deep into the northern peninsula. It served as Miletus’s military harbor and is named after two large lion statues flanking its entrance; one statue survives intact, the other in fragments. The harbor shore features a 32-meter-long L-shaped Doric stoa with commercial and storage spaces. In the Roman period, two large monuments known as the Great and Small Monuments were erected at the harbor’s southwest corner. The city’s main commercial agora, the Northern Agora, is located nearby.

Nymphaeum

The nymphaeum is located on the eastern side of the central square opposite the Buleuterion. Built around 79–81 CE, its background building is three stories high and resembles a Roman theater scaenae frons (stage backdrop). Each floor contains multiple niches and aediculae housing statues. The nymphaeum’s width is about 20.3 meters, and the water basin measures approximately 16.2 by 6.4 meters.

Other Remains

A heroon (hero shrine) dedicated to Neileus, the legendary founder of Miletus, was probably located near the Sacred Gate. A Roman-era aqueduct approximately 2 kilometers long supplied water from springs on nearby hills. Archaeologists discovered a cave beneath the theater, believed to be a sacred cave related to the cult of Asklepios. The site also includes remains of various smaller structures such as stoas, shops, and residential buildings, though many are fragmentary or only partially excavated.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations at Miletus have yielded numerous artifacts spanning from the Neolithic through Late Antiquity. Pottery assemblages include amphorae, tableware, and storage jars, reflecting both local production and imported wares. Inscriptions on stone and metal provide dedicatory formulas, official decrees, and references to civic offices, primarily from the Classical and Hellenistic periods. Coins from Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman authorities attest to the city’s long economic activity.

Tools related to agriculture, crafts, and industry have been found in domestic and workshop contexts. Domestic objects such as lamps, cooking vessels, and furniture fragments appear in residential quarters. Religious artifacts include statuettes, altars, and ritual vessels associated with Apollo, Athena, Serapis, and other deities worshipped in the city. These finds collectively illustrate the economic production, trade connections, and religious practices of Miletus’s inhabitants over time.

Preservation and Current Status

The ruins of Miletus vary in preservation. The city walls, especially those from the Hellenistic and Roman periods, survive in substantial sections, though some areas are fragmentary. The theater retains significant structural elements, including seating and the stage building, though parts are collapsed. The Faustina Baths are among the best-preserved complexes, with many architectural details intact. Other structures, such as the agoras and gymnasia, survive in partial form, with foundations and some columns visible.

Restoration efforts have stabilized many walls and public buildings, but most remain in their original archaeological state without modern reconstruction. The Market Gate of Miletus was excavated and transported to Germany, where it was reassembled and is exhibited at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. Ongoing excavations and conservation are conducted by Ruhr University of Bochum and Turkish authorities. Environmental factors, including sedimentation and vegetation growth, continue to affect the site, but no specific threats are detailed in recent reports.

Unexcavated Areas

Several parts of Miletus remain unexcavated or only partially studied. Surface surveys and geomorphological research indicate buried remains beneath sediment layers, especially in areas formerly closer to the ancient coastline. Some districts, including residential quarters and peripheral sanctuaries, await systematic excavation. Future fieldwork is planned to clarify the city’s occupational history and environmental changes, though no detailed excavation schedule or limitations due to modern development are specified in current sources.