Jerash: An Ancient City in Jordan with Extensive Greco-Roman and Byzantine Heritage

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.6

Popularity: Very High

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: international.visitjordan.com

Country: Jordan

Civilization: Byzantine, Early Islamic, Greek, Roman

Remains: City

Context

The archaeological site of Jerash is situated in northern Jordan, approximately 48 kilometers north of the capital, Amman. It occupies a gently rolling terrain characterized by low limestone hills and intersected by seasonal wadis, providing fertile conditions conducive to sustained human settlement. The modern city of Jerash lies immediately adjacent to the ancient ruins within the administrative boundaries of Jerash Governorate.

Stratigraphic and material evidence attest to continuous human activity at Jerash from the Bronze and Iron Ages through successive cultural phases. The site’s location within the northern Jordanian highlands positioned it strategically along historic caravan routes, facilitating trade and cultural exchange. During the Roman period, Jerash was incorporated into the Decapolis, a league of ten cities granted a degree of autonomy under Roman oversight. The Byzantine era is marked by a pronounced Christian presence, documented through numerous church remains and epigraphic sources. A major seismic event in 749 CE caused widespread destruction, significantly diminishing urban occupation. Since the nineteenth century, Jerash’s ruins have attracted scholarly and archaeological attention, with systematic excavations commencing in the early twentieth century and continuing under the Jordanian Department of Antiquities. The site’s extensive urban fabric and monumental architecture remain accessible for study, though preservation varies across different sectors.

History

Jerash’s historical trajectory spans from prehistoric settlement through Hellenistic colonization, Roman imperial integration, Byzantine Christianization, and early Islamic governance. Its evolution reflects broader regional dynamics in the Near East, including shifts in political control, religious transformations, and economic developments. Jerash’s status as a member of the Decapolis and later as a Roman colonia underscores its administrative and cultural significance within the Roman provincial system. The city’s fortunes were shaped by military conflicts, imperial patronage, and natural disasters, notably the earthquake of 749 CE, which precipitated a marked decline in urban scale and activity.

Prehistoric and Bronze Age Occupation

Archaeological investigations have revealed that Jerash was inhabited as early as the Neolithic period, circa 7500–5500 BCE. Excavations uncovered rare human skulls from this era, among the few such finds globally, linking Jerash to a network of early settlements in northern Jordan, including the prominent site of ‘Ain Ghazal near Amman. This evidence situates Jerash within a broader pattern of early human habitation in the Levant. During the Bronze Age, approximately 3200–1200 BCE, material remains such as pottery and architectural fragments confirm continuous occupation, with finds dating between 2500 and 700 BCE. These layers indicate a long-standing settlement predating the city’s later urban development.

Hellenistic Period (4th–1st century BCE)

Following Alexander the Great’s conquests, Jerash—known in antiquity as Gerasa or Antioch on the Golden River—was established as a Hellenistic city in the 4th century BCE. Local tradition and epigraphic evidence attribute its foundation to Alexander’s general Perdiccas around 331 BCE, who settled Macedonian veterans in the area. Alternative historical accounts credit Seleucid King Antiochus IV Epiphanes or Ptolemy II of Egypt with the city’s foundation or enhancement. Under Seleucid rule, the city was referred to as “Antioch on the Chrysorrhoas,” reflecting its Hellenistic cultural identity. In 84 BCE, Hasmonean King Alexander Jannaeus besieged and captured Gerasa, incorporating it into the Kingdom of Judea; archaeological layers indicate destruction of public buildings during this conquest. Gerasa’s strategic position on caravan routes contributed to its growth as a regional urban center during this period.

Roman Conquest and Administration (63 BCE – 3rd century CE)

In 63 BCE, Roman general Pompey ended Hasmonean control and incorporated Gerasa into the Decapolis, a league of ten autonomous Hellenistic cities under Roman protection. The Jewish historian Josephus described Gerasa as predominantly inhabited by Syrians with a small Jewish minority; notably, during the First Jewish–Roman War, the city protected its Jewish residents and facilitated their safe passage to the border. In 106 CE, Gerasa was integrated into the Roman province of Arabia, alongside Philadelphia (modern Amman), Petra, and Bostra, benefiting from imperial security and economic development. Emperor Trajan enhanced regional infrastructure, including roads that improved trade connectivity. Emperor Hadrian’s visit around 129–130 CE was commemorated by the construction of the Arch of Hadrian.

During the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, Gerasa reached its zenith, with an estimated population of approximately 20,000. The city was elevated to colonia status by Emperor Caracalla in 217 CE, conferring Roman citizenship rights on its inhabitants. The urban plan adhered to Roman city design principles, featuring a principal north-south street (cardo maximus) paved with large limestone slabs and lined with Corinthian and Ionic columns. This was intersected by two east-west streets (decumani), with monumental gates marking the northern and southern entrances. Public architecture included two major temples dedicated to Zeus and Artemis, two theatres, an oval forum supported by a substantial substructure and surrounded by Ionic columns, a hippodrome with a seating capacity of 15,000, a macellum (market), two large bath complexes, a monumental nymphaeum (fountain), and a nearly complete city wall fortified by approximately 120 watchtowers. Inscriptions attest that affluent citizens financed many of these constructions. The hippodrome, dating to the 2nd or 3rd century CE, hosted chariot races and spectacles, featuring vaulted seating and multiple access points. The Arch of Hadrian is a richly ornamented triple-arched monument approximately 13 meters high.

Late Roman and Byzantine Period (4th–7th centuries CE)

Following the Christianization of the Roman Empire under Emperor Constantine in 324 CE, Gerasa became an episcopal see and witnessed the construction of at least fourteen churches between the 4th and 7th centuries CE. The earliest cathedral, erected in 365 CE on the site of a former temple to Dionysus, was designed as a three-aisled basilica with Corinthian columns. Other significant churches include the circular Church of St. John (circa 531 CE), the basilicas of St. George (530 CE), Sts. Cosmas and Damian (circa 533 CE), and the Church of Bishop Genesius (611 CE). Archaeological evidence, including Hebrew-Aramaic inscriptions beneath church floors, indicates that some churches were adapted from earlier pagan temples or synagogues.

During this period, the city’s inhabited area contracted to approximately 80 hectares, about one-quarter of its Roman peak, reflecting demographic decline. The Persian Sassanids invaded and sacked Gerasa in 614 CE. In 636 CE, the Byzantine army was defeated by Muslim forces at the Battle of Yarmuk, resulting in the region’s incorporation into the Rashidun Caliphate. Seismic activity, particularly the earthquake of 749 CE, caused extensive damage to churches and public buildings. The hippodrome ceased its original function and was repurposed for pottery workshops and later as a burial site. The northern theatre, active until the 6th century, was similarly converted into a pottery workshop. City walls were reconstructed on a reduced scale, enclosing a smaller urban footprint.

Umayyad Period (7th–8th centuries CE)

Under Umayyad rule, Jerash maintained its role as a commercial and manufacturing center. Numismatic evidence includes coins inscribed with the Arabic name “Jerash,” confirming continued economic activity. The city supported a substantial Muslim population coexisting with Christians, who continued to use their churches. An 8th-century mosque was constructed within the forecourt of a former Roman house. Ceramic production flourished, with locally made lamps bearing Arabic inscriptions identifying potters and Jerash as their place of manufacture. The earthquake of 749 CE inflicted severe damage, accelerating the city’s decline and reducing large-scale urban occupation.

Crusader Period (12th century CE)

By the 12th century, Jerash’s urban fabric was largely in ruins. In 1120 CE, Zahir ad-Din Toghtekin, atabeg of Damascus, established a small garrison and constructed a fortress on the northeastern city walls’ highest point. In 1121–1122 CE, Baldwin II, King of Jerusalem, captured and destroyed this fortress. Subsequently, the Crusaders abandoned Jerash, retreating to the nearby settlement of Sakib. The precise location of the Crusader fortress remains uncertain but is unlikely to have been the Temple of Artemis, contrary to earlier assumptions.

Mamluk and Ottoman Periods (13th–19th centuries CE)

During the Mamluk Sultanate, Jerash was reduced to small rural settlements, particularly in the Northwest Quarter and near the Temple of Zeus, where domestic structures and Middle Islamic pottery have been excavated. Ottoman tax records from 1596 document Jerash (Jaras) as a village comprising twelve Muslim households engaged in agriculture and animal husbandry. By the 19th century, the site was largely abandoned and described as ruins. In 1886, Circassian immigrants were settled in the area under Ottoman auspices, revitalizing the locality through agricultural land distribution.

Modern Rediscovery and Excavation (20th–21st centuries CE)

Systematic archaeological excavations at Jerash commenced in 1925, involving international teams alongside Jordanian authorities. The site is recognized as one of the best-preserved Greco-Roman cities outside Italy, often referred to as the “Pompeii of the Middle East.” Excavations have uncovered numerous monuments, including the Arch of Hadrian, temples of Zeus and Artemis, theatres, the oval forum, the cardo maximus, the hippodrome, baths, markets, and city walls. Recent discoveries include marble statues of deities such as Aphrodite and Zeus, and a lead sarcophagus bearing Christian and pagan iconography dating to the late 4th or 5th century CE. Two archaeological museums on site display artifacts spanning from prehistory to Islamic periods. Jerash hosts an annual cultural festival featuring reenactments of Roman military drills, gladiatorial combat, and chariot races. The modern city has expanded eastward, preserving the archaeological site on its western side.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Hellenistic Period (4th–1st century BCE)

During the Hellenistic era, Jerash—then Gerasa or Antioch on the Golden River—developed as a city founded by Macedonian veterans settled by Perdiccas around 331 BCE. The population was culturally diverse, comprising Greek-speaking settlers and indigenous Semitic groups. Social stratification included military colonists, local elites, and artisans, though detailed records of officials are limited. Economic activities centered on agriculture, exploiting the fertile limestone hills and seasonal wadis to cultivate cereals, olives, and fruit trees. The city’s position on caravan routes facilitated trade, enabling exchange of local produce and imported goods. Public spaces likely hosted markets and social gatherings, while religious life combined Hellenistic cults with local traditions, as later evidenced by temples dedicated to Zeus and Artemis. Civic organization followed typical Hellenistic polis models, with magistrates and councils, though epigraphic evidence from this period remains sparse.

Roman Conquest and Administration (63 BCE – 3rd century CE)

Under Roman rule, Gerasa’s population expanded to an estimated 20,000 inhabitants, predominantly Syrians with a Jewish minority. The social hierarchy included wealthy Romanized elites who sponsored monumental public works, merchants, artisans, and a small number of slaves. Civic officials such as duumviri are attested epigraphically, indicating structured municipal governance. The economy was based on agriculture—olive oil, cereals, and fruit—alongside manufacturing activities including pottery, textiles, and metalworking. The macellum served as a central marketplace for food and goods, including imports facilitated by improved Roman roads. Transport relied on animal-drawn carts along the cardo maximus and caravan routes. Domestic architecture featured mosaic floors and painted walls, with houses arranged around courtyards. Diet included bread, olives, fish, and local fruits, supported by botanical and kitchen remains. Public amenities such as baths, theatres, and the hippodrome provided venues for social interaction and entertainment. Religious life was initially polytheistic, centered on temples to Zeus and Artemis, with rituals reinforcing civic identity. The city’s elevation to colonia status under Caracalla in 217 CE affirmed its administrative and cultural prominence within the province of Arabia.

Late Roman and Byzantine Period (4th–7th centuries CE)

Following its Roman peak, Jerash experienced demographic contraction, with the urban area reduced to approximately 80 hectares and a smaller population. The community became predominantly Christian, organized under a bishopric with at least fourteen churches constructed between the 4th and 7th centuries. Social stratification included ecclesiastical leaders, wealthy patrons, artisans, and farmers. Inscriptions name bishops and benefactors, indicating an active religious elite. Economic activities focused on sustaining local needs, with continued agriculture, pottery production, and small-scale crafts. The hippodrome and northern theatre ceased entertainment functions and were repurposed for pottery workshops and burial grounds, reflecting changing social customs. Domestic architecture retained mosaic decoration, while some pagan temples and synagogues were converted into churches, illustrating religious transformation. Markets persisted on a reduced scale, with trade likely more localized. Transport relied on animal caravans and foot traffic within the contracted city. Religious life centered on Christian worship, with basilicas and baptisteries hosting liturgical ceremonies. The city suffered Persian invasion in 614 CE and Muslim conquest in 636 CE, marking shifts in political authority. Jerash evolved into a smaller ecclesiastical center within the Byzantine provincial framework.

Umayyad Period (7th–8th centuries CE)

Despite prior decline, Jerash maintained commercial and manufacturing functions under the Umayyad Caliphate. The population included a sizable Muslim community coexisting with Christians, evidenced by continued church use and the construction of an 8th-century mosque within a repurposed Roman house. Social stratification incorporated Muslim religious leaders, local artisans, and Christian clergy. Economic life emphasized ceramic production at workshop scale, with locally made lamps bearing Arabic inscriptions naming potters and Jerash as their origin. Agriculture persisted, supporting the urban population. Markets likely offered both traditional and Islamic goods, with trade facilitated by regional networks. Transportation continued via animal caravans and local roads. Domestic interiors show continuity in household layouts, with Islamic influences in decoration and function. Religious practices reflected Islamic worship alongside Christian traditions, indicating a pluralistic society. The earthquake of 749 CE severely damaged the city, leading to a marked decline in urban occupation and economic activity. Jerash’s status shifted toward a diminished regional center within the early Islamic world.

Crusader Period (12th century CE)

By the 12th century, Jerash’s urban fabric was largely ruined, yet it briefly gained military significance when Zahir ad-Din Toghtekin established a small garrison and fortress on the northeastern city walls. The population was minimal, likely comprising soldiers and a few local inhabitants. Social organization was militarized, with limited civilian economic activity. Economic functions were restricted to supporting the garrison, with agriculture in surrounding areas sustaining the settlement. The fortress’s destruction by Baldwin II and subsequent Crusader abandonment ended Jerash’s brief military role. Transport was primarily by foot or animal along existing routes, facilitating troop movements rather than commerce. Religious life during this period is poorly documented but likely reflected the broader Christian-Muslim conflicts of the region. Jerash’s civic role was negligible, serving as a transient military outpost rather than a functioning urban center.

Mamluk and Ottoman Periods (13th–19th centuries CE)

Following the Crusader period, Jerash was reduced to small rural settlements, with a population engaged mainly in agriculture and animal husbandry. The Mamluk era saw limited habitation, particularly in the Northwest Quarter and near the Temple of Zeus, where domestic structures and pottery indicate modest village life. Ottoman tax records from 1596 list twelve Muslim households cultivating wheat, barley, olives, and tending goats and beehives. Economic activity was predominantly subsistence-based, with small-scale production supporting local needs. Trade was minimal, focused on nearby markets. Housing was simple, lacking monumental decoration, consistent with rural village patterns in northern Jordan. Religious life was Islamic, with local mosques serving the community, though Christian presence was negligible. Jerash functioned as a minor agricultural village within Ottoman administrative structures, lacking urban governance or significant civic institutions.

Remains

Architectural Features

Jerash’s urban layout is distinguished by a well-preserved orthogonal grid plan centered on the Cardo Maximus, the principal north-south street paved with large limestone slabs and lined with Corinthian and Ionic columns. This thoroughfare is intersected by two east-west decumani, each marked by monumental tetrapylons (four-way arches). The city was originally enclosed by walls extending over approximately 210 hectares, fortified with around 120 watchtowers. These walls, primarily constructed during the Roman period using ashlar masonry of local limestone, were later rebuilt on a reduced scale in Byzantine times, reflecting the city’s contraction. Preservation of the walls is fragmentary, especially on the eastern side, where modern development has caused significant loss. Monumental buildings exhibit a range of construction techniques, including marble cladding, vaulted arches, and hypocaust heating systems in bath complexes. Residential areas occupy smaller sectors, often reusing or adapting public structures. The city’s fabric reveals a predominantly civic and religious character, with urban contraction evident after the 7th century.

Key Buildings and Structures

Hadrian’s Arch

Constructed in 129–130 CE to commemorate Emperor Hadrian’s visit, Hadrian’s Arch is a triple-arched gateway situated approximately 400 meters outside the original city walls, beyond the hippodrome. The central arch measures about 13 meters in height, 7 meters in width, and 6.5 meters in depth. Built from ochre-yellow limestone, the arch features four half-pillars on each side, with bases adorned by finely carved acanthus leaf motifs. Both the northern and southern façades are identical; the southern side has undergone restoration, while the northern side remains partially ruined due to earthquake damage. Niches once housed statues, now lost. An inscription on the north-facing side honors Emperor Hadrian. Restoration efforts between 2003 and 2008 restored the arch to its original height of 21 meters and a width exceeding 25 meters.

Hippodrome

The hippodrome is the largest surviving structure at Jerash, dating to the 2nd or 3rd century CE. It measures 241 meters in length and 51 meters in width, with seating arranged in fifteen rows of vaulted seats accessible via six entrances. Three additional entrances provided direct access to the arena. Vaulted spaces beneath the seating accommodated storerooms and shops. Excavations uncovered remains of stables in the southern section. Although now in a ruined state, the hippodrome was a central venue for chariot races, athletic competitions, and public spectacles. Tombs carved into the surrounding rock date to Roman and Byzantine periods. In later phases, the hippodrome was repurposed, possibly serving as a caravan resting place.

South Gate

Dating to the 1st century CE, the South Gate served as the principal entrance for travelers arriving from Philadelphia (modern Amman). It comprises three arches similar in style to Hadrian’s Arch, flanked by half-columns decorated with acanthus leaf carvings. Wheel ruts from ancient carts remain visible in the paving to the gate’s left. Originally, the gate was flanked by guard towers, which have not survived. The gate led directly into the city’s core, where cultic and representative buildings were concentrated.

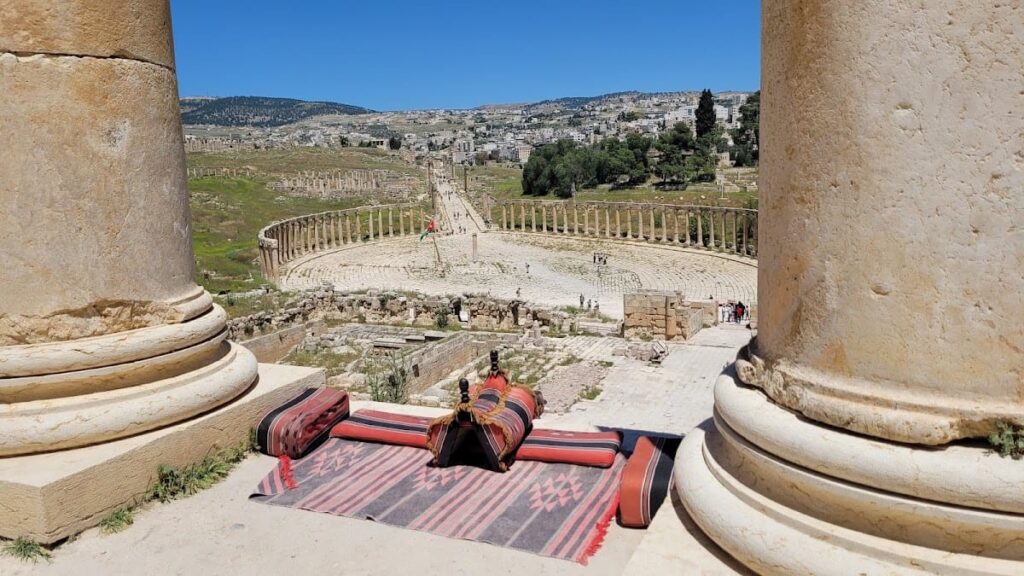

Oval Forum

Located in a natural depression in the southern sector of the city, the Oval Forum measures approximately 90 by 80 meters. It is bordered on both sides by wide sidewalks lined with 56 Ionic columns connected by an architrave. The spaces between columns housed shops. The forum’s stone-paved surface features larger slabs on the outer rings emphasizing its elliptical shape, with a differently paved center. A monument once stood at the center but was converted into a well in the 7th century, supplied by water from a northern cistern. Inscriptions on the eastern colonnade record the names of citizens who financed its construction. A modern symbolic flame column is erected here during the annual Jerash Festival. The forum’s function remains debated, with interpretations ranging from religious association with the nearby Temple of Zeus to economic or commercial use.

Temple of Zeus

Perched on a hilltop with cultic significance dating to the Iron Age, the Temple of Zeus primarily dates to 162 CE, constructed atop an earlier temple from between 22 and 69 CE, itself built over a Hellenistic structure. The temple platform measures 41 by 28 meters and is surrounded by a wide staircase and originally an arcade of vaulted arches. The cella was enclosed by eight columns on the short sides and twelve on the long sides, each approximately 15 meters tall. Interior walls were clad in marble, and the rear wall housed a statue of Zeus. Only the foundations of the vaulted arcade remain, as most columns and walls have collapsed. The temple exhibits Syro-Nabataean architectural features, including a staircase leading to the roof of the cella.

South Theatre

Constructed circa 90–92 CE west of the Temple of Zeus, the South Theatre was restored in 1953 and remains in use for cultural events. It is fully enclosed, with seating arranged in 32 rows accommodating an estimated 3,500 spectators. Stone seats bear numbers, likely indicating reserved seating, with numbering proceeding from right to left starting at the bottom row. The lowest row was reserved for city elites and honored guests. The upper seating area is divided into eight sectors, accessible from a hill behind the theatre. Acoustic niches are carved into the stage podium base. The theatre is oriented north-south to minimize sun glare. The stage includes two vaulted side doors and three architecturally integrated entrances. Naval battle reenactments were staged by flooding the arena using waterproof partitions.

Cardo Maximus and Tetrapylons

The Cardo Maximus, the main north-south street, was originally constructed in the late 1st century CE and expanded in the 2nd century. It is paved with large limestone slabs and lined with Corinthian columns, measuring approximately 12.3 meters wide in the northern section and 12.6 meters in the southern. Two east-west decumani intersect the Cardo, each marked by a tetrapylon (four-way arch). The southern tetrapylon was particularly monumental; only four wide bases with niches remain. Each tetrapylon supported four columns topped by statues, with surrounding walkways that housed shops or later residential spaces. The northern tetrapylon, built in the 2nd century CE, originally featured four arches supporting a dome and a base decorated with fountains. The northern Cardo retains Ionic capitals, while Corinthian capitals appear in the southern section. Wheel ruts from carts are visible near the southern tetrapylon. A drainage system beneath the street managed rainwater. Approximately 500 columns remain standing along the Cardo.

Nymphaeum

Constructed around 190 CE, the nymphaeum is a monumental fountain dedicated to water nymphs. It measures about 20 meters wide with a concave façade divided into two horizontal levels. Corinthian columns adorn the structure, and the upper half-dome interior was likely decorated with mosaics. The two-tiered wall contains seven niches on each level, which held statues of deities and nymphs. Water flowed from statues on the lower level into a large granite basin dating to the Byzantine period. From there, water passed through seven lion-head spouts into six smaller basins before entering the drainage system beneath the Cardo. The nymphaeum served as a social gathering place in the city center.

Propylaea (Temple of Artemis Gate)

The monumental entrance to the Temple of Artemis is marked by a propylaea connected by a stairway designed with a visual effect: from below, seven ramps of seven steps each appear as a single staircase, while from above it looks flat. Four columns flank the entrance, each standing 16 meters high and 1.5 meters in diameter.

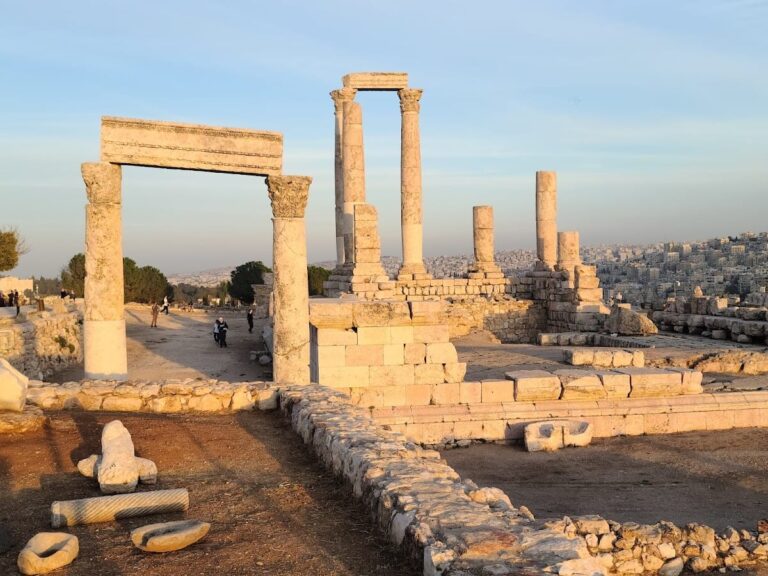

Temple of Artemis

Constructed circa 150 CE, the Temple of Artemis occupies a platform measuring 161 by 121 meters. The temple terrace rises 4.5 meters high, with the temple itself measuring 42 by 41 meters. The cella is surrounded by eleven columns on the long sides and six on the short sides, each 13 meters tall and 1.75 meters in diameter, topped with Corinthian capitals. Some columns incorporate special joints allowing slight movement. The pronaos featured two staircases leading to an outer colonnade with five gates opening into the inner courtyard. The sacred precinct (temenos) contained an altar behind the temple. The marble-clad sanctuary had a wooden roof, now lost, but the cella remains well preserved. Excavations suggest the temple was never fully completed. During Byzantine and Umayyad periods, the temple housed a pottery workshop. Later, the Damascus governor converted part of it into a fortress, which was destroyed by King Baldwin II.

Western Baths

Dating to the 2nd century CE, the Western Baths are possibly the largest Roman bath complex in present-day Jordan, though only a small portion has been excavated. The complex follows a typical Roman bath layout with three main vaulted sections: caldarium (hot water), tepidarium (warm water), and frigidarium (cold water). It includes changing rooms and several large pavilions. The baths served both hygienic and social functions.

Byzantine Churches

Fourteen churches and one chapel have been excavated, mostly dating from the 4th to 7th centuries CE. Most are basilicas, some with simple domes, richly decorated with colorful mosaics on floors and walls. Many churches are located near the Temple of Artemis. Notable examples include the Cathedral (built in the 4th century and expanded in the 5th), the circular Church of St. John (circa 529 CE) with four columns, the basilica of St. George (consecrated 530 CE), the single-nave Church of Saints Cosmas and Damian (circa 533 CE) with geometric and figurative mosaic floors, and the Church of Bishop Genesius (built 611 CE), the last Christian church in Jerash. Mosaic floors depict animals, plants, crosses, human figures, allegorical seasons, and Egyptian cities such as Alexandria and Memphis. Inscriptions commemorate local dignitaries who financed construction. Some churches were converted from earlier Roman buildings or synagogues.

Cathedral

The earliest Christian building in Jerash, the Cathedral was constructed in 365 CE on the site of a former temple to Dionysus. It is a three-aisled basilica with apses; only the decorated entrance and floor plan remain. Built entirely from reused Roman architectural elements, twelve Corinthian columns separate the nave from the aisles. A chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary, dating to the 5th century, is attached to the eastern wall. The courtyard behind the cathedral likely served as a forecourt with three entrances. It is paved with rectangular pink sandstone slabs and contains the bishop’s stone throne and a basin.

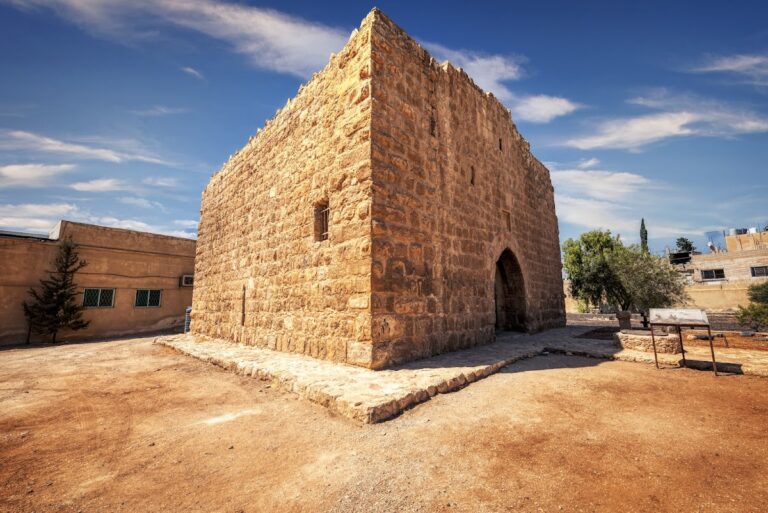

Umayyad Mosque

Located on the left side of the road in front of the Temple of Artemis’s propylaea, the Umayyad Mosque was built in the 8th century within the forecourt of a Roman house. The mihrab was adapted from a former decorative niche.

North Theatre

Inaugurated in 164 CE and expanded around 222 CE, the North Theatre was used until the 6th century CE. Seating was dedicated to various deities, with many seats bearing tribal names, a unique feature in the eastern Roman provinces. The lowest seats were reserved for city council members. The theatre was roofed and initially served as a meeting and gathering place. Seating is arranged in two parts: 14 rows in the lower section and 8 rows added during the 3rd-century expansion. Upper seats were accessed via five covered corridors. Seating capacity is estimated at about 1,600 spectators. Later, the theatre was repurposed as a pottery workshop. It was severely damaged by a 6th-century earthquake, and many columns and architectural elements were reused in church construction.

North Gate

Built around 115 CE during Emperor Trajan’s reign, the North Gate replaced an earlier gate. Construction was overseen by Claudius Severus, who was also responsible for the road from Pella to Jerash. The gate consists of a single arch measuring 9 meters high and 5.4 meters wide. It is flanked by half-columns with simple bases and two niches on each side for statues. An inscription above the arch records the date and circumstances of construction. The gate is asymmetrical, with the western side wider to connect the Cardo to the road from Pella.

Macellum (Market)

The Macellum, dating to the early 2nd century CE, is a central commercial building initially mistaken for the city’s agora or political forum. It functioned as a food market, featuring an octagonal central area where money changers operated. Stone lions supported a bench used for displaying goods. The floor was decorated with mosaics. Numerous shops lined the surrounding streets.

Other Temples

A temple beneath the Church of St. Theodore is probably dedicated to Dionysus. Another temple, known as “Temple C,” is reduced to foundations, and its dedication remains unknown.

City Walls

The city walls originally enclosed about 210 hectares, extending 3.5 kilometers in length, 2–3 meters in width, and 4–5 meters in height. They were fortified with approximately 120 watchtowers. Most walls have been destroyed, especially on the eastern side due to modern development. The city was accessible through four gates: two monumental gates to the north and south, and two smaller gates to the west. Walls were rebuilt in later periods, reducing the city’s size and excluding the area between the South Gate and Hadrian’s Arch, including the hippodrome.

Domestic Structures

Remains of houses mostly represent reoccupation of Roman public buildings. Two houses on the eastern side of the wadi feature mosaic floors depicting Bacchic processions and the four seasons. The “House of the Blues” is named after an inscription found there. A well-preserved Byzantine-Umayyad residence with visible remains dates mainly to the Arab period. A residential quarter northwest of the Church of St. Theodore was excavated in the 1930s, likely housing clergy members; it has since been reburied. The “Clergy House,” still visible, is thought to have housed clergy, though its exact function remains uncertain.

Baths

Two large bath complexes near the northern tetrapylon are mostly collapsed. The “Baths of Placcus,” located west of the wadi near the Church of St. Theodore and the Clergy House, are poorly excavated but appear large. Hypocaust heating furnaces remain visible. A late 5th-century inscription attributes construction to Bishop Placcus.

Other Religious Buildings

A 4th-century synagogue located northwest of the Temple of Artemis was later converted into a church.

Archaeological Discoveries

Artifacts from Jerash span from prehistoric to Islamic periods. Excavations have uncovered numerous marble statues, including a group identified as the Muses of the Olympic pantheon, discovered in 2016 and partially restored. A well-preserved lead sarcophagus dating to the late 4th or 5th centuries features Christian and pagan symbols. Sculptures, altars, and mosaics are displayed outdoors near the site. Pottery finds include locally produced ceramics such as lamps bearing Arabic inscriptions naming local potters and Jerash as their origin, especially from the Umayyad period. Coins from various periods, including Roman and Umayyad, have been found, confirming ongoing economic activity. Inscriptions on forum columns and churches commemorate citizens and dignitaries who financed construction. Tools and domestic objects have been recovered from workshops and residential areas, illustrating craft and daily life. Religious artifacts include statuettes, altars, and ritual vessels associated with temples and churches.

Preservation and Current Status

Jerash is among the best-preserved Greco-Roman cities outside Italy, though preservation varies across the site. Major monuments such as Hadrian’s Arch, the hippodrome, theatres, temples, and city walls survive in varying states of completeness. Hadrian’s Arch underwent restoration between 2003 and 2008, regaining its original height and width. The South Theatre was restored in 1953 and remains in use. Other structures, including the hippodrome and baths, are largely in ruins but retain significant architectural elements. Some churches and domestic buildings are partially preserved, with mosaic floors and architectural fragments visible. The city walls are fragmentary, especially on the eastern side. Ongoing archaeological work and conservation are conducted by the Department of Antiquities of Jordan and international teams. Some areas are stabilized but not fully restored to preserve original fabric. Environmental and human impacts have affected parts of the site, but systematic excavation and conservation continue.