Herculaneum Archaeological Park: Preserved Roman Municipium at the Foot of Mount Vesuvius

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.8

Popularity: High

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: ercolano.cultura.gov.it

Country: Italy

Civilization: Roman

Remains: Burial, City, Civic, Domestic, Economic, Entertainment, Infrastructure, Religious, Sanitation

Context

The Archaeological Park of Herculaneum is situated within the modern municipality of Ercolano, part of the Metropolitan City of Naples in southern Italy. Positioned on a coastal plain along the Bay of Naples, the site lies at the foot of Mount Vesuvius, whose volcanic activity profoundly influenced the town’s development and ultimate fate. The surrounding landscape features volcanic slopes and access to maritime routes, factors that shaped Herculaneum’s urban planning and economic connections.

Initial settlement traces date to the 6th century BCE, with archaeological evidence indicating Oscan and Samnite presence prior to Roman incorporation. The town expanded notably under Roman rule from the 1st century BCE onward, becoming a municipium within the Campanian province. Its occupation ceased abruptly in 79 CE when the eruption of Mount Vesuvius buried the city beneath pyroclastic flows and mud. The volcanic deposits preserved organic materials and wooden structures exceptionally well, providing a rare archaeological record.

Rediscovered in the early 18th century, Herculaneum has since been the focus of systematic excavations and conservation efforts. These continue today, aiming to stabilize fragile remains and manage the impact of visitors, thereby safeguarding the site’s archaeological integrity and facilitating ongoing research into its historical and cultural significance.

History

The Archaeological Park of Herculaneum encapsulates a long trajectory of settlement and transformation, reflecting broader regional dynamics in Campania and the Roman world. Its history is characterized by early Italic habitation, integration into Roman political structures, and sudden destruction during the 79 CE eruption of Mount Vesuvius. Subsequent rediscovery and excavation have revealed a well-preserved urban environment that offers insight into ancient municipal life and imperial influence.

Pre-Roman Period (12th century BCE – 89 BCE)

Archaeological and literary sources trace Herculaneum’s origins to the 12th century BCE, with initial settlement by Oscan-speaking peoples. Strabo and other ancient authors suggest possible Etruscan involvement between the 10th and 8th centuries BCE, while Greek forces briefly controlled the area in 479 BCE, integrating it into Mediterranean cultural networks. The town later came under Samnite influence, reflecting the complex ethnic and political landscape of pre-Roman Campania. These early phases laid the groundwork for Herculaneum’s urban and social structures prior to Roman conquest.

During this period, the settlement developed defensive walls primarily in opus caementicium with large cobbles, dating mostly to the 2nd century BCE. The walls enclosed a relatively small urban area, with access points oriented toward the sea. The town’s location on a coastal plain near volcanic slopes provided both strategic advantages and environmental challenges, shaping its early growth and interactions with neighboring communities.

Roman Conquest and Municipal Development (89 BCE – 79 CE)

Following the Social War (91–88 BCE), Roman forces conquered Herculaneum in 89 BCE, granting it municipium status. This designation conferred local self-government under Roman law and integrated the town into the administrative framework of the Campanian province. The urban layout was formalized according to the Hippodamian grid plan, featuring three main east-west decumani and five north-south cardines, with streets paved in lava slabs during the Augustan period. Defensive walls, originally constructed in the 2nd century BCE, lost their military function after the Social War and were incorporated into urban buildings.

Under Roman rule, Herculaneum evolved into a residential center favored by the Roman elite, particularly during the tenure of Marcus Nonius Balbus, a local magistrate and benefactor who sponsored significant urban improvements. The city was connected to the Serino aqueduct, constructed in the Augustan age, which supplied water through lead pipes equipped with valves. The earthquake of 62 CE caused substantial damage, prompting reconstruction efforts that included the addition of brick column porticoes as seismic reinforcements. The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE abruptly ended the city’s occupation, burying it beneath 10 to 25 meters of volcanic ash, lapilli, and mud. This deposit solidified into a soft rock known as “pappamonte,” preserving the city’s structures and organic materials.

Post-Destruction and Rediscovery (79 CE – 18th century)

After the catastrophic eruption, Herculaneum remained buried and largely forgotten for over sixteen centuries. Unlike Pompeii, the pyroclastic material sealed wooden structures and organic remains, resulting in exceptional preservation. The site was accidentally rediscovered in 1709 during well-digging near the church of San Giacomo. Early explorations by Prince Emanuele Maurizio d’Elboeuf uncovered marble columns, statues, and inscriptions, initiating scholarly interest.

Systematic excavations began under King Charles of Bourbon in 1738, led by Roque Joaquín de Alcubierre and later Karl Jakob Weber, who advocated for open-air excavation methods. The discovery of the Villa of the Papyri in 1750 intensified research, revealing a vast collection of carbonized papyrus scrolls and statuary. Excavation activity declined by 1780 due to richer finds at Pompeii and logistical difficulties, leaving much of the site unexplored and inaccessible.

Modern Excavations and Conservation (19th century – Present)

Excavations resumed intermittently in the 19th century under the Bourbon monarchy, adopting open-air methods but yielding limited new discoveries. The appointment of Amedeo Maiuri as superintendent in 1924 marked a turning point, with extensive excavations from 1927 to 1942 uncovering approximately four hectares. Maiuri introduced the concept of an open-air museum, restoring buildings immediately after excavation, though this approach was later reconsidered due to preservation challenges.

Post-World War II efforts focused on securing and restoring the site, with further excavations continuing until the late 1950s and a brief campaign in the 1960s. From 1980 onward, investigations along the ancient shoreline revealed over 300 human skeletons, providing direct evidence of the eruption’s human toll and the inhabitants’ attempts to escape by sea. The site’s inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1997, alongside Pompeii and Oplontis, recognized its global cultural significance.

The Herculaneum Conservation Project, initiated in 2001 in partnership with the Packard Humanities Institute, has prioritized preservation, expanded excavations, and improved visitor access. The formal establishment of the Archaeological Park of Herculaneum in 2016 consolidated management and conservation efforts. Recent rehabilitation of the ancient beach area, reopened in 2024, has further enhanced understanding of the site’s final moments and its broader historical context.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Roman Conquest and Municipal Development (89 BCE – 79 CE)

Following its incorporation as a Roman municipium, Herculaneum’s population comprised Roman citizens, local Oscan and Samnite descendants, freedmen, artisans, merchants, and enslaved individuals. The social hierarchy is evidenced by residential quarters and workshops, with prominent figures such as Marcus Nonius Balbus exemplifying the local elite who influenced civic and urban development. Gender roles aligned with Roman norms, with men occupying public offices and women managing domestic spheres, as suggested by household inscriptions and spatial organization.

Economic activities included small-scale manufacturing, commerce, and agriculture adapted to the coastal environment. Archaeological finds document workshops producing metal goods, textiles, and engraved precious stones, alongside thermopolia and bakeries serving residents and visitors. Maritime trade was facilitated by the town’s coastal position, with amphorae bearing Greek inscriptions indicating imported goods. Dietary staples included olives, grapes, cereals, fish, and locally cultivated fruits.

Residential architecture featured well-appointed homes, generally smaller than those in Pompeii but richly decorated with frescoes, mosaics, and stucco. Houses incorporated courtyards, private wells, kitchens, and elaborately painted rooms, balancing functionality and aesthetic refinement. Post-62 CE earthquake reconstructions introduced brick column porticoes as seismic reinforcements. Public amenities comprised baths with advanced heating and water systems, a theater, and a forum serving as centers for social, religious, and administrative activities.

Religious life is attested by temples dedicated to Venus and the Four Gods, and the Augustales’ college, reflecting organized cultic practices. Inscriptions reveal dedications by local families and magistrates, underscoring the integration of religion and politics. Communal events such as festivals and banquets fostered civic identity. Herculaneum functioned as a municipium with self-governance under Roman law, administered by magistrates and councils, and served as a residential and commercial hub favored by Roman elites seeking coastal retreats.

Post-Destruction and Rediscovery (79 CE – 18th century)

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE abruptly terminated urban life in Herculaneum, preserving the city beneath thick pyroclastic deposits. For over sixteen centuries, the site remained buried and devoid of population or economic activity. The exceptional preservation of organic materials and wooden structures provides a unique archaeological snapshot of Roman daily life frozen at the moment of disaster.

Rediscovery in the early 18th century initiated a new phase of scholarly and archaeological interest. Initial explorations uncovered statues, inscriptions, and architectural fragments, revealing the city’s former civic and residential character. Although no active population or economy existed, the site’s importance shifted to cultural heritage and historical study. Excavations during this period laid the foundation for understanding Roman urbanism and social organization, while daily life as a lived experience ceased with the eruption.

Modern Excavations and Conservation (19th century – Present)

Modern archaeological efforts, beginning in the 19th century and intensifying under Amedeo Maiuri in the 20th century, have expanded knowledge of Herculaneum’s urban fabric and social dynamics. Excavations revealed detailed evidence of domestic life, including workshops, shops, and residential quarters belonging to freedmen and aristocrats alike. The discovery of over 300 human skeletons along the ancient shoreline illuminated the final moments of the inhabitants, many of whom attempted escape by sea.

Conservation projects have emphasized preserving fragile frescoes, mosaics, and carbonized wooden elements, enabling more accurate reconstructions of interior decoration and household organization. Findings confirm a complex social hierarchy, with elite residences such as the House of the Inn featuring private baths and elaborate decoration, alongside modest homes and workshops indicative of a diverse urban population engaged in various trades. Clothing and personal adornment are inferred from artistic depictions and artifacts consistent with Roman norms.

The religious landscape includes temples, shrines, and the Augustales’ college, reflecting sustained cultic practices and social cohesion. Public buildings such as baths and the theater highlight communal leisure and cultural life. Transport and commerce were supported by the city’s coastal position and road connections, facilitating regional trade and mobility. Herculaneum’s role has evolved into a key archaeological and educational resource, illustrating Roman municipal life and urban resilience prior to its destruction.

Ongoing excavations and conservation within the Archaeological Park continue to enhance understanding of daily life and the city’s regional significance, preserving its legacy as a municipium balancing residential comfort, commercial activity, and religious observance within the dynamic environment of the Bay of Naples.

Remains

Architectural Features

Herculaneum was enclosed by city walls primarily constructed in the 2nd century BCE, described by the historian Lucius Cornelius Sisenna as relatively small, with thickness ranging between two and three meters. The walls were built mainly using dry stone masonry with large cobbles, while sections along the coastline employed opus reticulatum, a net-like pattern of small tuff blocks. Following the Social Wars, these fortifications lost their defensive function and were incorporated into adjacent buildings, such as the House of the Albergo. The urban plan follows a Hippodamian grid with three main east-west streets (decumani) and five north-south streets (cardines), of which two decumani and three cardines are excavated and visible. Ramps and arched gates near the walls provided direct access to the sea.

The city’s architecture reflects a predominantly residential and civic character, comprising private houses, public baths, religious buildings, and commercial establishments. Construction materials include tuff, brick, cocciopesto (a waterproof mortar), and marble used for flooring and decorative elements. Post-62 CE earthquake renovations introduced seismic reinforcements such as brick column porticoes. The 79 CE eruption preserved much of the urban fabric beneath pyroclastic deposits, including rare carbonized wooden elements.

Key Buildings and Structures

House of the Albergo

The House of the Albergo is the largest known residential structure in Herculaneum, covering over 2,000 square meters and situated in a panoramic location overlooking the sea. Dating mainly to the late Republican and early Imperial periods, it uniquely contains a thermal quarter with a calidarium (hot bath) decorated with mosaics and second-style frescoes. The peristyle and adjacent rooms feature mosaic flooring, while substructures beneath the house have cocciopesto and polychrome marble floors. The building incorporates sections of the city walls, illustrating the post-Social War integration of fortifications into urban fabric.

House of the Skeleton

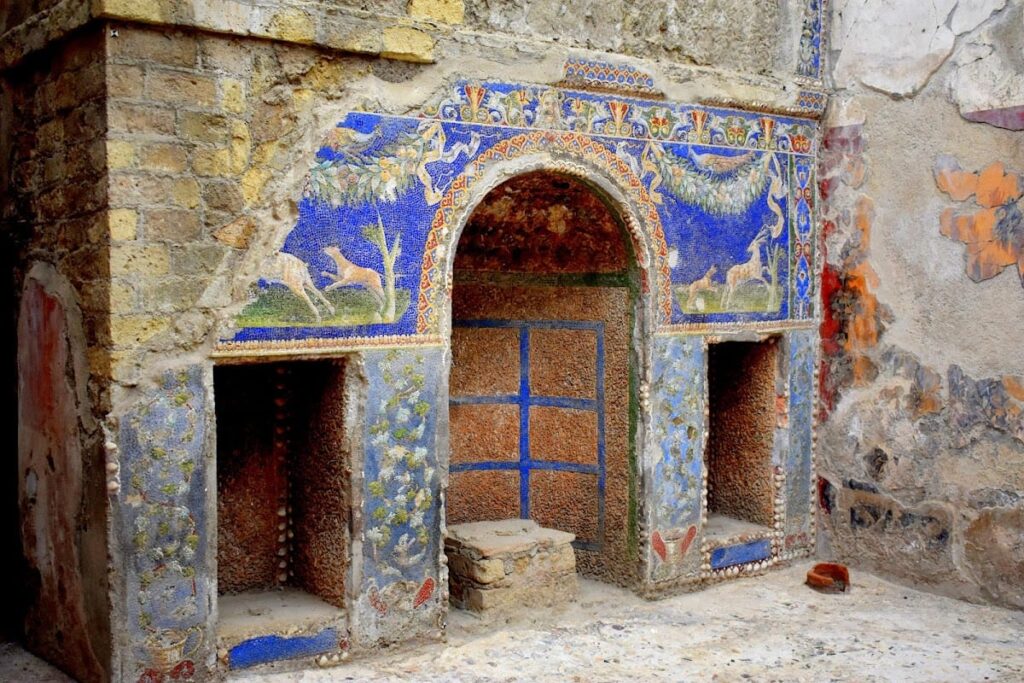

Formed by the union of three earlier houses, the House of the Skeleton was partially explored during Bourbon excavations and named after a skeleton found inside. Re-excavated in 1927, it contains a nymphaeum designed to imitate a grotto, covered with faux ashlar masonry (opus quadratum) using red and blue tesserae, with frescoed friezes. The courtyard, protected by a metal grate, preserves a lararium (household shrine) decorated with mosaics. Other rooms retain third-style frescoes and opus sectile (cut stone) flooring.

House of the Wooden Partition

Originally constructed before the Roman conquest and restored during the Julio-Claudian period, this house is named for a folding wooden door (tramezzo) with shaped panels and bronze lamp supports separating the atrium from the tablinum (main reception room). The garden features a fountain depiction surrounded by images of a duck, heron, snake, and bull’s head. Wall decorations are in the third style.

House with Wattle Walls

This multi-family dwelling is built almost entirely in opus craticium, a construction technique employing thin wooden frameworks filled with materials and plastered over. The plaster was applied over two layers of reeds fixed with nails. Externally, the house has a balcony supported by three brick columns. Interior decoration includes fourth-style frescoes. Carbonized furniture such as beds and wardrobes were found inside, containing glass vessels, lararia statuettes, lamps, and a necklace.

House of the Bronze Herm

A small house featuring cocciopesto flooring and third-style wall decorations, it includes a tuff impluvium (water basin in the atrium). Some rooms contain fourth-style frescoes and opus sectile flooring in the tablinum and triclinium (dining room). A bronze herm (sculptural bust) of the owner was discovered here; a cast is exhibited.

House of the Brick Altar

Covering approximately 110 square meters and divided into six rooms, this house includes an atrium and an upper floor. Its interior decorations are sparse and mostly second style, with significant damage.

House of the Mosaic Atrium

Located in a panoramic position utilizing the ancient city walls for terracing toward the sea, this house features geometric mosaic flooring at the entrance and a vestibule inspired by coffered ceilings. The atrium floor displays a checkered mosaic pattern. The tablinum has a basilical layout with three naves, stucco-covered pillars, and opus sectile marble flooring. The garden is surrounded by a fenestrated triportico with frescoes depicting scenes such as “The Punishment of Dirce” and “Diana and Actaeon.” A central marble fountain is fed by a reservoir situated on the house’s entrance floor.

House of the Alcove

Resulting from the union of two houses with independent entrances connected by a door in the vestibule, the first house was heavily looted during Bourbon excavations, leaving only a fresco of Ariadne abandoned by Theseus. The second house preserves opus sectile and mosaic floors and several fourth-style frescoes. A small, fenestrated, apsidal room called the alcove is accessed via a short corridor.

House of the Fullonica

Dating to the 2nd century BCE, this house contains two atria: one without an impluvium, later converted into a fullonica (laundry) with two washing basins, and another Tuscan-style atrium with a cocciopesto impluvium. First-style wall decorations survive in two rooms.

House of the Painted Papyri

Named after a fresco on the courtyard entrance door depicting a papyrus scroll with the Greek name of a poet and two inkwell cases, this house is notable for its association with the nearby Villa of the Papyri.

House of the Cloth

A small-sized house composed of two levels accessed by two staircases, one from the street and another from the shop. Several cloths were found here, indicating its use related to textile production or trade.

House of the Deer

Named for a garden statue depicting two deer attacked by dogs and a satyr with a wineskin, the owner was identified as Celer, a freedman, from a stamp on carbonized bread. The house is divided into a reception quarter, servant quarter, and a large corridor. The fenestrated cryptoporticus contained about sixty small paintings of cupids, still lifes, and deities; some were removed during Bourbon times and are now housed in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples, while others remain in situ.

House of the Great Portal

This house features an entrance portal constructed after the 62 CE earthquake, with semi-columns bearing tuff capitals decorated with winged victories and a brick corbel cornice. The internal plan is irregular due to continuous expansions. It contains a peristyle with fluted tuff columns, a triclinium with frescoes depicting a satyr observing Ariadne and a nude Dionysus, a yellow-painted exedra with birds and cupids, and a diaeta with blue background frescoes illustrating trophies, masks, and weapons. All decorations are in the fourth style. Three amphorae labeled as containing chickpeas, flour, and rice were found.

House of the Wooden Shrine

Constructed before the Roman conquest, this house is evidenced by first-style wall paintings, a cenaculum (dining room), and cocciopesto flooring with geometric motifs and white tesserae. It is notable for a wooden cabinet externally decorated with Corinthian column motifs serving as a lararium; inside was a statuette of Hercules.

House of the Corinthian Atrium

This house features an atrium supported by six tuff columns and a marble mosaic fountain in the impluvium. Several rooms preserve fourth-style frescoes. The vestibule is decorated with brick columns.

House with Shop (L. Cominius Primus)

Belonging to L. Cominius Primus, a freedman likely employed as a scribe or public clerk (actuarius), as indicated by a seal. Wax tablets containing economic notes on land purchases and boundary regulations were found in a box in an upper floor cubicula (bedroom).

House of the Bicentennial

Named because excavation concluded in 1938, two centuries after the start of Herculaneum excavations. Built in the Augustan period entirely in opus reticulatum, it features a tablinum with opus sectile flooring and fourth-style frescoes, including a panel depicting Daedalus and Pasiphae. It contains a sliding wooden gate protecting ancestor images. The upper floor, constructed in opus craticium, yielded wax tablets narrating legal actions. The house also contains a painted lararium, vegetable fiber brooms, and a seal. A cross-shaped form found in a wall was initially interpreted as early Christian evidence but later identified as a shelf support.

House of the Beautiful Courtyard

Renovated during the Claudian period with mosaic flooring and third-style frescoes, though some second-style fresco remains. It features a mosaic courtyard with stairs and masonry balconies providing access to upper floors. Decorations were unfinished at the time of the eruption, as evidenced by a sketch of an eagle. The house was used as storage for archaeological finds during excavations.

House of Neptune and Amphitrite

Two marble slabs painted in red monochrome and signed by Alexander of Athens were found here, possibly by the same artist who painted the “Players of Astragali” panel now in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples. The tablinum wall contains a glass tessera mosaic depicting Neptune and Amphitrite. The attached shop functioned as a caupona (inn), containing dolia with fava beans and chickpeas, carbonized wooden furniture, and utensils such as a stove and shelves.

House of the Carbonized Furniture

This residence follows a typical Roman layout with atrium, tablinum, garden, and upper floor. Dating to the Claudian age and later remodeled with third-style frescoes replacing earlier decorations. The triclinium contains still-life frescoes and a carbonized wooden bed restored shortly after the 62 CE earthquake. The garden includes a shell-niche lararium.

House of the Loom

Featuring two entrances—one to the workshop and one to the house—the portico contained remains of a wooden weaving loom. Two slits provided light to the workshop. A marble plaque was found inside.

Samnite House

Dating to the 2nd century BCE but significantly reduced in the 1st century BCE. The atrium has tuff Corinthian columns, first-style wall decorations, a coffered ceiling with second-style frescoes, and a marble-veneered impluvium. Many decorations were redone in the fourth style after restorations. The house has an upper floor accessed by two staircases. The tablinum has a diamond-shaped mosaic floor with a central copper tile. A cubicula contains a green-background fresco depicting the abduction of Europa.

House of Apollo Citharista

Completed after the 62 CE earthquake by merging the House of the Bicentennial and the House of the Beautiful Courtyard. Contains fourth-style frescoes and opus sectile flooring framed by mosaics. Tablinum frescoes depict Apollo the citharist and Selene with Endymion. The attached shop contained semi-buried dolia with cereals and legumes.

House of the Brick Column

Approximately 110 square meters divided into seven rooms. The house lacks any decoration.

House with Garden

A small house without decorative elements. Contains an oecus (reception hall) with second-style frescoes, mostly Nile landscapes. It has a large garden, possibly added after the 62 CE earthquake. Adjacent to a small artisan shop with a lararium.

House of the Two Atria

Named for having two atria: one tetrastyle and the other with an impluvium and two cistern mouths. It has an upper floor, mostly collapsed. Some rooms preserve intact fourth-style frescoes with still-life motifs. The kitchen retains a counter with an oven. The exterior façade is built in opus reticulatum decorated with terracotta masks.

House of the Tuscan Colonnade

Dating to the 2nd century BCE, extensively renovated and expanded in the Augustan age. Preserves cocciopesto atrium flooring from the earlier period. The Augustan phase features a Tuscan colonnade in the peristyle, marble floors, and well-preserved third-style frescoes. The oecus contains panels depicting a Maenad and Panisco and a conversation between two women. The upper floor yielded several gold coins and a seal. An adjacent shop with red and blue frescoes houses numerous marble inscriptions collected from various public buildings.

House of the Black Hall

Owned by freedman Lucius Venidius Ennychus, as evidenced by twenty wax tablets. Preserves carbonized wooden doorposts, architrave, and part of the door. Features a black fourth-style decorated room at the back of the peristyle with white mosaic flooring. Contains a wooden sacellum, several Corinthian marble capitals, and an adjacent bronze worker’s shop. The bronze workshop contained repair items such as a statue of Dionysus and a chandelier.

House of the Relief of Telephus (Insula Orientalis I)

Owned by Marcus Nonius Balbus, built in the Augustan age and fully restored after the 62 CE earthquake. Atrium columns support upper floor rooms. The diaeta and oecus are fully marble-clad with sea views. Notable for numerous Neo-Attic statues, including eight marble oscillating statues and a high relief of the myth of Telephus, with a cast available for viewing.

House of the Gem (Insula Orientalis I)

Adjacent to the Suburban Baths, it contains a residential quarter and a servant quarter located one floor below near the bathhouse roof. The servant quarter, built in the late Republican age using part of the city walls, has vaulted ceilings and mosaic floors. Due to vapors from nearby baths, the servant quarter was reserved for servants. Artifacts found include a wooden cradle with remains of a child, two marble slabs depicting Hercules fighting the Hydra, an Egyptian sphinx, a box filled with glassware, a bronze seal, and two cornelian stones.

House of Galba (Insula VII)

Partially excavated and named after a silver bust of Servius Sulpicius Galba found near the entrance, now in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples. Dates to the Samnite period. Features a peristyle with Doric tuff columns, kitchen, latrines, and a staircase to the upper floor.

House of the Relief of Dionysus (Northwest Insula)

Named for a relief inserted in a 1st-century fresco depicting a dancing Maenad and a bearded man, probably Dionysus. Another relief shows three women and a man; a statue of Dionysus holding a kantharos on a pedestal was also found. Dates to the late Republican age, later expanded and under renovation at the time of the eruption. Discovered in 1990 and only partially excavated. Revealed fourth-style red-background frescoes and black-and-white mosaic flooring.

House of M. Pilius Primigenius Granianus (Suburban Area)

Located near the ancient shoreline with panoramic sea views. Interiors contain second-style frescoes and mosaic floors.

Villa of the Papyri

The only otium villa found in Herculaneum, located outside the city walls. Discovered in 1750 and explored via tunnels until 1761, it remains partially buried under over 25 meters of pyroclastic material from the 79 and 1631 eruptions. Damaged by the 62 CE earthquake and under restoration at the time of the eruption. The frontage exceeds 250 meters in length. It belonged to L. Calpurnius Piso Pontifex or Appius Claudius Pulcher. The villa contains 58 bronze and 21 marble statues and a library of over 1,800 carbonized papyri in boxes, with philosophical texts in Latin and Greek. Known parts include a rustic quarter centered on a garden with jars channeling water into a decorative canal, and an atrium near which a bronze sundial was found. New rooms with wall decorations and mosaic floors have been uncovered since the 2000s.

Forum Area

The forum remains almost entirely buried and unexcavated. It does not follow the traditional rectangular Roman forum layout but is divided into two parts by a marble-covered arch decorated with frescoes and statues. The eastern part hosted civic activities, while the western part was used for economic functions. Access for carts was prohibited.

Basilica Noniana

Constructed during the Augustan period and restored after the 62 CE earthquake by Marcus Nonius Balbus. Mostly still buried, only a section of the perimeter wall along Cardo III is exposed. The basilica has a rectangular plan with an exedra at the back and a double order of semi-columns along the perimeter. Numerous statues were found inside, including equestrian types depicting Balbus’s family, a marble head with traces of hair and eye coloring, and fourth-style frescoes such as the labors of Hercules. Explored between 1739 and 1761 via tunnels. The building is similar to the Eumachia building in Pompeii, with two side porticoes and an apse decorated with frescoes of Hercules finding his son Telephus, Theseus and the Minotaur, Chiron instructing Achilles, Pan, and Olympus. Two marble equestrian statues of Balbus and a bronze one were found. Porticoes and chalcidicum had opus sectile flooring. The chalcidicum is visible, with an entrance arch decorated with fourth-style stuccoes including a reclining satyr. Inside are three marble-clad bases that held statues.

Monument to Marcus Nonius Balbus

Located near the Suburban Baths in a large square. Balbus was a prominent benefactor who restored and built public buildings. His funerary altar faces the sea, with a marble base that once held a statue of Balbus dressed in armor. The statue was partially destroyed by the eruption; the head was found during Maiuri’s excavations, and the rest of the body was discovered in 1981.

Suburban Baths

Located outside the city walls near Porta Marina and the funerary area dedicated to Marcus Nonius Balbus. Among the best-preserved ancient thermal structures. Used by both men and women who shared the same spaces. Large windows along perimeter walls and skylights on the roof provide illumination. The entrance leads to two service rooms for controlling bathers, where numerous graffiti, including erotic ones, were found. The atrium contains a marble herm of Apollo. The waiting/massage room preserves intact stuccoes depicting nude warriors. The calidarium retains a wooden door leaf. The tepidarium is mostly occupied by a pool. The laconicum floor mosaic depicts a crater with ivy tendrils.

Forum Baths

Built in the Julio-Claudian period with perimeter walls in opus reticulatum and opus incertum. Internally divided into male and female sections, largely following the layout of Pompeii’s Forum Baths. The female section preserves several mosaics: a black-and-white corridor mosaic, a mosaic depicting Triton with a rudder in the apodyterium (changing room), and geometric, ivy leaf, and trident motifs in the tepidarium (warm bath). The male section also has mosaics, including a poorer-quality copy of the female Triton and several red-background frescoes with vases and candelabra. Both sections had pools connected to a complex hydraulic system with a water wheel.

Northwest Baths

Discovered in 1990; only part of the complex has been excavated. Oversized relative to the city’s needs, possibly serving visitors from surrounding areas. The exposed part, initially thought to be a temple but later identified as the calidarium, is almost intact and still roofed. Illuminated by numerous windows with carbonized wooden jambs and niches likely for statues. Interior walls are coated with travertine and mortar imitating a grotto. An apse contains a nymphaeum flanked by two small doors leading to a rear room. The central pool was used for hot baths. Part of a colonnade nearby was excavated, where a boat and a carbonized horse skeleton were found. A marble staircase leading to the sea was adorned with fountains, pools, and gardens.

Palaestra

Two-thirds excavated. Along Cardo V side, a series of shops with small rented apartments above. The entrance is flanked by two partly collapsed columns and a once starry-painted vault, now fragmentary. The interior features a Corinthian triportico and a large central garden with a bronze hydra-shaped fountain and a rectangular basin used as a hatchery. The basin had embedded amphorae in the wall for egg deposition but was already out of use at the eruption. The central hall likely contained statues of Julio-Claudian family members, never found. A marble table was discovered. Side rooms have third-style frescoes. Numerous statues of Egyptian deities were found inside, probably brought by the eruption from the nearby yet unexcavated Temple of Isis.

Theatre of Herculaneum

The first building of the city to be discovered and the earliest of all Vesuvian archaeological sites. Located in a peripheral area of the archaeological park, still mostly buried and accessible only through tunnels. It has a typical Roman theatre layout with a seating area exceeding 2,500. The cavea (seating area) was decorated with numerous bronze statues, some equestrian, many lost due to being melted down in Bourbon times for coinage. Two gilded bronze seats were found in the orchestra area. Several marble inscriptions were discovered. Behind the theatre was a porticoed area in Hellenistic style used for spectators’ leisure during intermissions.

Sacred Area (South of the City)

Located near the coastline on a terrace supported by vaulted structures. Contained two temples dedicated to Venus and the Four Gods. Finds include two mythological frescoes, two headless statues of women in tunics, and a marble altar dedicated to Venus, plus various terracotta objects. The Venus sacellum, built in the southern part of the sacred area, was fully restored after the 62 CE earthquake by Sibidia Saturnina and her son Furio Saturnino. Adjacent to the temple is a marble altar; pronaos columns are tuff, stuccoed and fluted. The cella has a vaulted ceiling and walls with garden fresco remains, including a rudder symbolizing Venus guiding sailors. The Four Gods sacellum was also restored after the earthquake. Inside were four archaistic reliefs depicting Minerva, Mercury, Neptune, and Vulcan, protectors of commerce and production. The pronaos has Corinthian columns and a cipollino marble floor; the cella floor is opus sectile. The wooden roof was recovered, having been blown onto the beach by the eruption.

Collegium of the Augustales

Built between 27 and 14 BCE during Augustus’s lifetime, to whom it was dedicated. On inauguration day, brothers Lucius Proculus and Lucius Iulianus hosted a banquet for the Senate and Augustales. The building has a square plan with walls featuring blind arches, four central columns, and cocciopesto flooring. The upper floor was constructed in opus spicatum (herringbone brickwork). Most frescoes are fourth style, including depictions of Hercules in Olympus with Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva, and Hercules with Achelous. It hosted numerous statues found during Bourbon excavations, including Augustus and Claudius as Jupiter holding a thunderbolt, and statues of Marcus Nonius Balbus’s family. The custodian’s skeleton was found inside, lying on a bed. Nearby is a small sacellum with a rectangular plan and a podium on the back wall, opening onto the main decumanus.

Thermopolium with Wine Jars

A thermopolium (ancient food and wine shop) was found containing jars with wine produced in Herculaneum.

Taberna of Priapus

Named for a fresco of Priapus on the counter. Inside was a dolium containing walnuts.

Vasaria Taberna

Lacking a sales counter, this shop contained numerous amphorae, including some black ones with Greek characters and terracotta vessels.

Plumbarius Shop

Connected directly to the atrium of the House of the Black Hall, likely rented out. Features a long white limestone block counter on the façade. Possibly a metallurgical workshop, evidenced by a crucible, terracotta cooling vessels, iron tools, lead ingots, and pipe fragments. Found a statuette of Bacchus decorated with gold, copper, and silver, and a bronze candelabrum with a marble base.

Ad Cucumas Shop

Connected to the House of the Black Hall. The entrance pillar bears a painted sign depicting four jugs (cucumae) of various colors with prices for different drinks. Above is a depiction of the Roman deity Semo Sancus. Below is a red inscription mentioning the city of Nola, where a gladiatorial show took place, possibly made by a traveling scribe named Aprilis in Capua. Next to the inn was a three-level shop; visible remains include a lateral stair beam and a carbonized rope.

Gemmarius Shop

Contained both worked and unworked precious stones. A wooden box with stone-carving tools was found. The shop also served as a residence, evidenced by a hearth, a well, and a bed with remains of a boy.

Lanarius Shop

Created from the House of the Wooden Partition, with an upper floor. Occupied by a cloth merchant. Consists of a square room with beaten earth flooring. Contained a carbonized wooden screw press used for wool processing; alternatively, it may have been used to distill perfumes from plant essences. One of the few surviving display cases, set up by Amedeo Maiuri, contained artifacts found on site.

Large Taberna near the Palaestra

Features an L-shaped counter covered with polychrome marble. Inside the counter are eight jars for foodstuffs. Marble shelves at the ends held dishes and tableware. Composed of several back rooms, one containing a ship painting and graffiti, including one in Greek.

Pistrina (Bakeries)

Two bakeries were found, smaller and fewer than in Pompeii, possibly because bread was made at home, as indicated by numerous millstones in houses. The bakery of Sex Patulcius Felix, named after a bronze seal found, contains two stone millstones and a kiln with an attached workshop, both protected by two stucco phallic symbols as good luck charms for baking. The upper floor held 25 circular bronze trays (placentae) of various sizes, possibly used for baking flatbreads.

Beach Area

Archaeological investigations under the Suburban Baths began in 1980 to create a new park entrance. Excavations between 1982 and 1983 reached the ancient coastline and beach of Herculaneum. Finds include shell remains and a boat, now displayed in a museum. The arches overlooking the beach yielded about 300 victims’ bodies who sought shelter during the eruption but were caught by pyroclastic flows. Personal belongings such as coins and jewelry were found with the victims. The area, prone to flooding and turned into a swamp, was reclaimed and reopened to the public in 2024.

Other Remains

The forum remains mostly unexcavated and buried beneath volcanic deposits. The Temple of Isis is mentioned in historical sources but has not yet been excavated. The city had only one sewer along Cardo III; other drainage was into the streets except for latrines, which had soak pits. The aqueduct of Serino, built in the Augustan age, supplied water via lead pipes under streets regulated by valves, though these were removed during Bourbon excavations. Earlier water supply came from wells 8 to 10 meters deep. Some buildings and necropolises remain buried and unexplored.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations at Herculaneum have uncovered a wide variety of artifacts spanning from the pre-Roman Oscan and Samnite periods through the Roman Imperial era. Pottery includes amphorae for storage and transport, tableware, and cooking vessels, many locally produced but with some imported examples. Numerous inscriptions have been found, including dedicatory formulas, legal documents on wax tablets, and graffiti in public and private spaces.

Coins from various emperors, especially from the Julio-Claudian dynasty, have been recovered, often in domestic contexts. Tools related to agriculture, crafts, and metallurgy have been documented, including iron implements, crucibles, and stone-carving tools. Domestic objects such as lamps, glass vessels, cooking utensils, and furniture fragments, including carbonized wooden beds and wardrobes, provide insight into daily life. Religious artifacts include statuettes, lararia, altars, and ritual vessels found in houses and sanctuaries.

Preservation and Current Status

The site’s preservation varies by structure. Many houses retain walls, floors, and decorative elements such as frescoes and mosaics, though some are fragmentary or heavily damaged. Wooden elements, including doors and furniture, survive in carbonized form due to the volcanic burial. Public buildings like the Suburban Baths and the Collegium of the Augustales are among the best-preserved. The Villa of the Papyri remains partially buried under pyroclastic deposits.

Restoration efforts have stabilized many fragile remains, though some areas have been reconstructed using modern materials, especially during the 20th century. Environmental threats include erosion and vegetation growth, while human impact is managed through conservation projects. Excavations continue selectively, with ongoing work focused on preservation and controlled access. Some areas are stabilized but left unexcavated to protect underlying deposits.

Unexcavated Areas

Significant portions of the forum remain unexcavated, as do some residential and public districts. The Temple of Isis is known from historical references but has not been explored archaeologically. Surface surveys and geophysical studies suggest buried remains beneath modern urban development and volcanic deposits. Future excavations are limited by conservation policies and the need to preserve the site’s integrity, as well as by modern infrastructure overlying parts of the ancient city.