Dublin Castle: Historic Seat of Power in Ireland

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.3

Popularity: Very High

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: dublincastle.ie

Country: Ireland

Civilization: Medieval European

Remains: Military

History

Dublin Castle is located in Dublin, Ireland, and was originally built by the Normans following their invasion of Ireland in the late 12th century. Its construction began in 1204 under Meiler Fitzhenry, acting on the orders of King John of England. The castle was established as a fortified stronghold to secure the Norman city of Dublin, serving both defensive and administrative purposes.

During the medieval period, Dublin Castle became the center of English authority in Ireland, maintaining this role through different political entities: the Lordship of Ireland starting in 1171, the Kingdom of Ireland from 1541, and later the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland after the Act of Union in 1801. It housed key officials such as the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland and the Chief Secretary for Ireland who governed on behalf of the English and British crowns.

Over the centuries, the castle’s functions expanded beyond military defense to include judicial and parliamentary activities. It also served as a military garrison and, during the turbulent years of the early 20th century, was involved in intelligence operations. During the Irish Civil War, the building temporarily accommodated the Four Courts following damage elsewhere in the city.

Dublin Castle has been at the heart of significant historical moments. In 1592, the Irish chieftain Red Hugh O’Donnell famously escaped the castle’s confines. In 1798, General Joseph Holt, a leader associated with the United Irishmen rebellion, was imprisoned here. The castle played a key role in events during the 1916 Easter Rising and the subsequent Anglo-Irish War, including the arrest and killing of Irish Republican Army (IRA) members on Bloody Sunday in 1920.

Following the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922, Dublin Castle ceased to operate as the seat of British government in Ireland. It transitioned into a ceremonial venue and has since hosted presidential inaugurations starting in 1938. Additionally, it has served as a setting for official state occasions such as the 2011 banquet honoring Queen Elizabeth II. Excavations carried out in 1986 revealed remnants of the original Norman defenses beneath the current structure, including parts of Viking fortifications predating the castle itself.

Remains

Dublin Castle was initially designed as a Norman courtyard castle, completed by around 1230. Its layout centered on a square open courtyard surrounded by imposing curtain walls and circular corner towers. Unlike many castles of the period, it lacked a traditional keep or central donjon. The castle’s position was strategically chosen to utilize the natural defenses offered by the nearby River Poddle and River Liffey, enhancing its protective capabilities with water features and moats.

Among the surviving medieval elements, the Record Tower, constructed circa 1228 to 1230, stands out. It is a robust circular tower originally part of the castle’s fortifications and was restored in the early 19th century. This tower later housed the Garda Museum, reflecting its adaptive reuse over time. Positioned at the southwest corner, the Bermingham Tower preserves its medieval stone base, topped by an upper section rebuilt in a more modern style. The identity of its namesake, likely connected to the De Bermingham family, remains uncertain.

Remnants of other medieval towers, including the Powder Tower at the northeast corner and the Storehouse Tower, survive in the castle’s basement areas. These structures demonstrate impressive defensive construction with walls measuring up to 3.7 meters thick, enclosing interiors about 6.1 meters in diameter. While only the lower sections remain visible today, their substantial masonry attests to the castle’s original strength.

The castle underwent significant transformation after a major fire in 1684, moving away from its medieval fortress origins toward an eighteenth-century Georgian palace style. Most buildings seen today date from this period, reflecting changes in both aesthetic preferences and functional requirements. The State Apartments, located in the southern range of the Upper Yard, were once the residence and official chambers of the Lord Lieutenant. These rooms feature elaborate decoration and have been preserved as part of the castle’s museum collection.

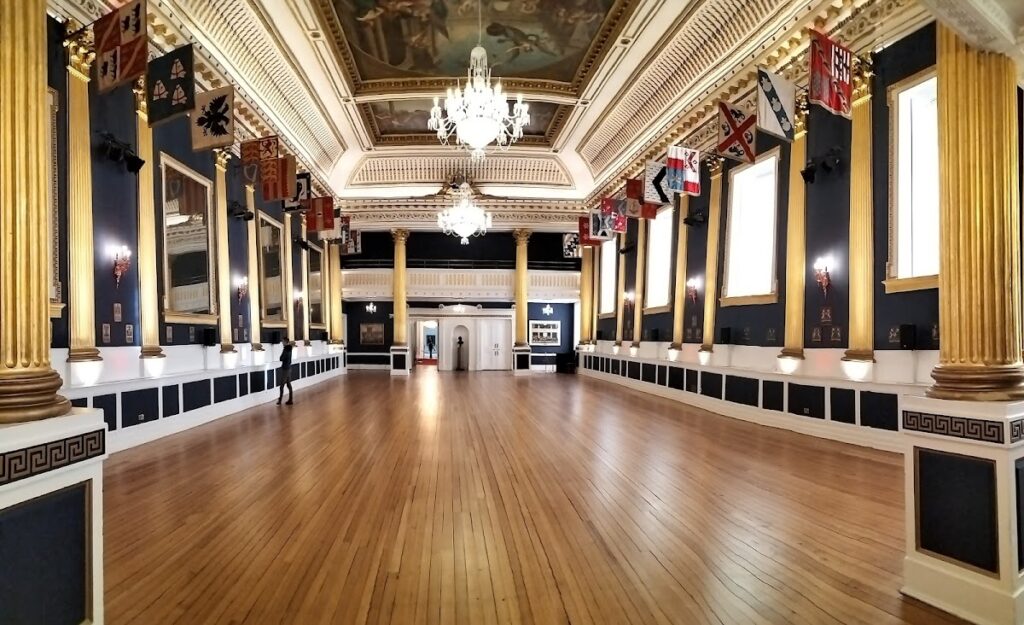

Notable interiors include St. Patrick’s Hall, a grand room with decorative elements mainly from around 1790. Its painted ceiling by Vincenzo Valdre depicts important historical themes such as the coronation of King George III, Saint Patrick’s introduction of Christianity to Ireland, and King Henry II receiving the submission of Irish chieftains. The hall also displays banners and hatchments linked to the Order of St. Patrick, connecting Ireland’s aristocratic traditions with its complex political history.

Other principal rooms in the State Apartments include the Throne Room, originally known as Battleaxe Hall and dating to the 1740s, which contains the throne made for King George IV’s visit in 1821. The State Drawing Room, rebuilt after a fire in 1941, is used to receive foreign dignitaries, while the State Dining Room (also called the Picture Gallery or Supper Room) retains its original mid-18th century decoration and serves dining functions during official events. The State Bedrooms, reconstructed in the 1960s after damage from fire, follow the original layout and were among the last to be used by a British Prime Minister during a visit in the 1980s.

Connecting these rooms is the State Corridor, built around 1758 by architect Thomas Eyre. It features a vaulted series of arches that were originally lit from above and showcase preserved plasterwork, doorframes, and fireplaces despite changes in later centuries. This corridor reflects the castle’s evolution from fortress to refined palace.

Later additions supplement the medieval and Georgian core. Bedford Tower, constructed between 1750 and 1761, is an example of 18th-century expansion within the complex. In contrast, a 20th-century office block designed by Frank du Berry interrupts the historical rectangular arrangement, illustrating changing needs over time.

A characteristic defensive feature of the original castle was the moat, which was artificially flooded by diverting the River Poddle through archways in the castle’s walls. At least one such archway and sections of the medieval wall survive underground and remain accessible to visitors. The Royal Chapel, part of the complex from 1814 until 1922, functioned as the private worship space for the Lord Lieutenant during the castle’s period as a seat of government.

Today, Dublin Castle’s grounds and buildings are well preserved. While much of the visible architecture reflects Georgian style, careful archaeological work has revealed medieval stonework and earlier defensive structures below ground, including formerly Viking-era fortifications upon which the Normans later built. This layered history is evident in the surviving fabric and in the castle’s ongoing role as a site of Irish heritage.