Crookston Castle: A Medieval Stronghold in Glasgow, Scotland

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.4

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.historicenvironment.scot

Country: United Kingdom

Civilization: Medieval European

Remains: Military

History

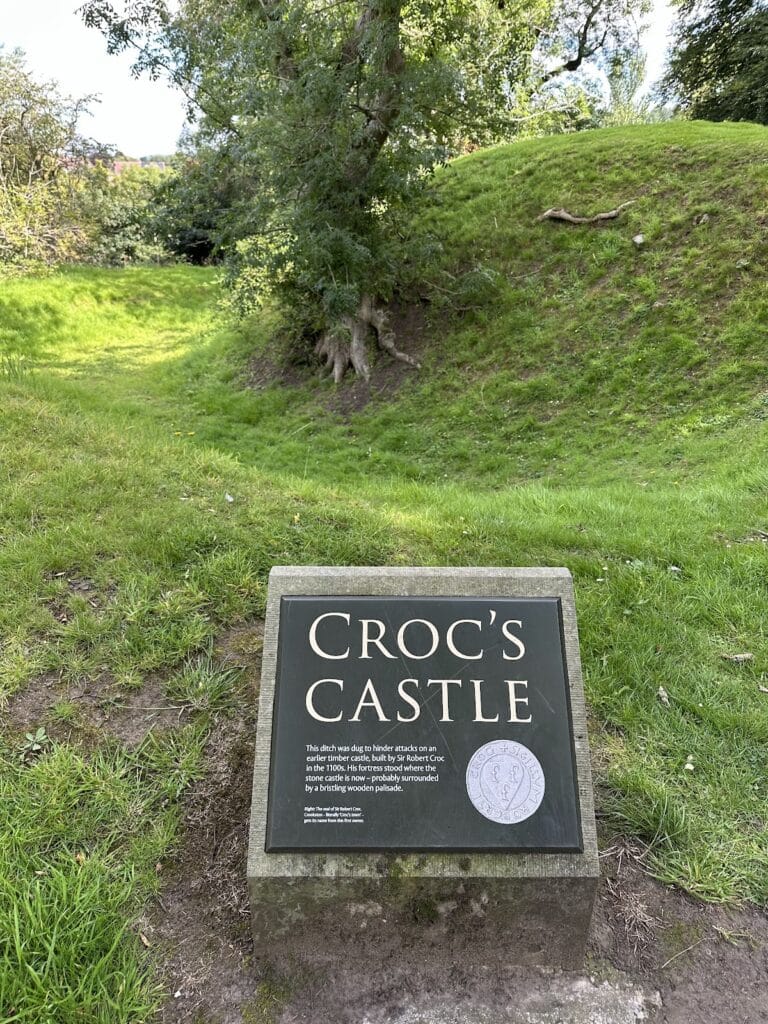

Crookston Castle is located in Glasgow, Scotland, and was constructed by medieval Scottish builders. The site originally hosted a timber and earthwork castle established in the 12th century by Sir Robert de Croc, a local landowner who also founded a chapel there in 1180. Archaeological evidence indicates that a fortification existed at this location even prior to de Croc’s construction, suggesting its longstanding strategic importance overlooking the nearby rivers.

In 1330, the lands containing the castle were acquired by Sir Alan Stewart, and shortly thereafter, in 1361, ownership transferred to Sir John Stewart of Darnley. Around the year 1400, the Stewarts replaced the early timber structure with a stone castle, which largely defines the ruins seen today. This phase marked a significant strengthening of the site’s defenses and residential capability, reflecting the family’s elevated status.

During a rebellion led by the Stewart Earl of Lennox in 1489, King James IV attacked Crookston Castle with artillery, including the famous cannon called Mons Meg. This bombardment severely damaged the western portion of the castle, prompting a rapid surrender by its defenders. The castle later played a role in the conflicts of the mid-16th century; in April 1544, it was besieged and captured by forces under the Earl of Arran and Cardinal Beaton while the Earl of Lennox was occupied defending Glasgow Castle. At that time, Crookston served as the main residence of the Earls of Lennox, underscoring its political and military significance.

Following this, five gunners were stationed in the castle by Regent Arran in May 1544 to maintain its defense. The castle also featured in noble domestic arrangements: it formed part of the dower lands belonging to Margaret Douglas, Countess of Lennox. A tradition suggests that her son Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley—who later married Mary, Queen of Scots—may have been betrothed at Crookston beneath a yew tree, which survived until its felling in 1816. A model of the castle was carved from the wood of this tree, symbolizing the site’s historical associations.

In 1572, the castle was officially granted to Charles Stewart, Earl of Lennox. Ownership later passed from the Stewarts to the Duke of Montrose in 1703, remaining within the Montrose family until 1757 when it was sold to the Maxwells of Pollok. After a period of neglect, the Maxwells undertook partial restoration in 1847, motivated by Queen Victoria’s visit to Glasgow. This restoration aimed to preserve the castle’s remains and commemorate its historical importance.

Crookston Castle entered a new phase of stewardship in 1931 when it became the first acquisition of the National Trust for Scotland. It was donated by Sir John Maxwell Stirling-Maxwell, an influential founder and the first Vice President of the Trust. During the Second World War, the castle’s north-eastern tower was repurposed as an aircraft watch tower, demonstrating its continued strategic use even in modern times. Today, the castle is a scheduled monument under the care of Historic Environment Scotland and stands as the second-oldest surviving building in Glasgow after the cathedral.

Remains

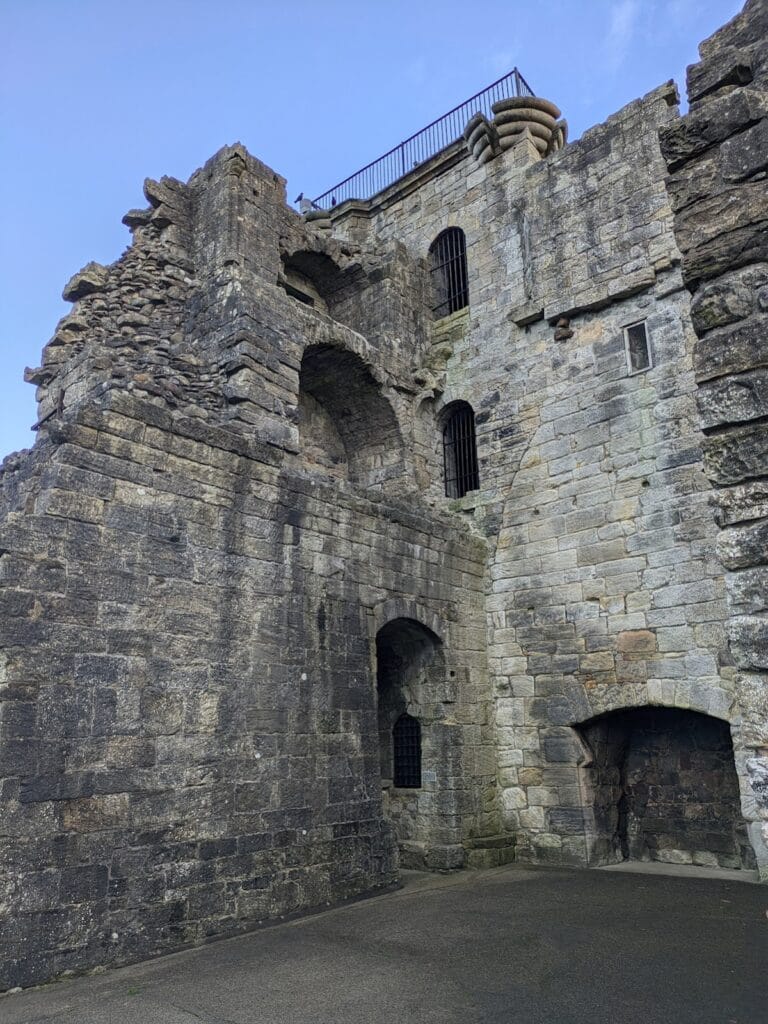

Crookston Castle is situated on a natural hill, which is enhanced by a defensive earthwork—a circular ditch dating back to the 12th century—that remains visible around the site. On the northern side, the land slopes steeply down toward the Levern Water, providing a natural barrier. The stone castle itself is built mainly from local masonry and follows an unusual design known as an ‘X-plan.’ This layout consists of a large rectangular main block approximately 19 meters long and 12 meters wide, reinforced by a tower positioned at each corner. The walls are notably thick, up to 3.7 meters, indicating a strong defensive purpose.

The towers create an irregular ‘X’ shape around the central structure, a style also seen in a few other Scottish castles such as Hermitage Castle. Among these, only the north-east tower remains intact up to its original height, standing roughly 6 meters square. The south-east tower’s basement survives, while the two towers on the western side were destroyed during the 15th century bombardment and were not reconstructed. Later repairs in the 19th century have obscured much of these western remains.

Access to the castle was controlled through an entrance on the north side beside the north-east tower. This doorway was protected by a portcullis, a heavy sliding grille used for defense, along with two sets of doors. Immediately inside, visitors would find a straight stair carved into the thickness of the wall, known as a mural stair, which ascends to higher levels. Directly ahead lies the barrel-vaulted basement, characterized by a curved stone ceiling resembling the interior of a barrel, which includes narrow slit windows for light and ventilation and a well that provided water.

The first floor housed the main hall, a large vaulted room measuring 8.3 meters high, serving as the principal living and meeting area. Above the hall, a turnpike stair—a spiral staircase—located in the south-east corner allowed entry to an additional floor and to rooms in the eastern towers. Each tower contained one room per floor, offering separate spaces likely used for lodging or storage.

Within the north-east tower’s basement was a prison space, unique in that it could only be accessed from above, making it secure and difficult to escape. Today, the four-storey tower is reachable through modern iron ladders installed during restoration, leading up to the roof where extensive views of the surrounding landscape can be enjoyed. The upper parts of this tower, including the structural supports called corbels that project outward from the walls, were rebuilt during the 19th-century repairs, blending historical preservation with necessary reconstruction.

Together, these features illustrate Crookston Castle’s evolution from a timber motte-and-bailey fortification to a formidable stone stronghold that adapted over centuries to changing military needs and noble residence standards. Its surviving structures offer insight into medieval Scottish castle design as well as the site’s layered history.