Château de Pennautier: A Historic 17th-Century Estate in Southern France

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.3

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.lorgeril.wine

Country: France

Civilization: Unclassified

Remains: Military

History

The Château de Pennautier, located in the town of Pennautier in southern France, was built in the early 17th century by the Languedoc civilization under the commission of Bernard de Reich de Pennautier. As treasurer of the Estates of Languedoc, Bernard established the château in 1620 during a period of recovery following the religious conflicts known as the Wars of Religion. Due to its impressive scale and refined design, the château acquired the nickname “the Versailles of Languedoc,” highlighting its prominence in the region.

In 1622, King Louis XIII visited the château while traveling to Perpignan, marking a moment of royal recognition. The king presented Bernard de Reich de Pennautier with his travelling furniture, including a canopy bed and six armchairs covered in tapestry, items that remain preserved in what is now called the “King’s chamber.” These furnishings hold historical significance and have been designated as protected monuments.

Bernard’s son, Pierre Louis Reich de Pennautier, who also held the treasurer role and became receiver general of the clergy in 1669, undertook significant enhancements beginning in 1670. He expanded the château’s structure and developed its formal French gardens. These improvements drew upon the expertise of notable architects and landscapers of the time, including contributions influenced by Louis Le Vau and André Le Nôtre. Besides his work on the château, Pierre Louis was an influential financier, involved in major projects such as the Canal du Midi and managing royal manufacturing enterprises. Among these was a large wool textile factory that at its height employed around two thousand workers, linking the estate closely to regional industry.

Ownership passed through inheritance to the Beynaguet family in the 18th century, who appended the château’s name to their own, becoming Beynaguet de Pennautier and acquiring the courtesy title Marquis de Pennautier. Jacques de Beynaguet, a military officer specializing in artillery and a traveler, enriched the château’s interior with a collection of artworks. His son, Rodolphe Beynaguet, active in the mid-19th century, made further structural modifications including enclosing the central courtyard to increase interior space. He also renovated the interiors, introducing Italian-style mosaic floors, while redesigning the surrounding park in the English landscape garden fashion, signaling a shift from the previous formal French style.

During the early 20th century, the Lorgeril family came to possess the estate through marriage. Starting in the 1920s, they conducted extensive renovations including the removal of a northeast wing damaged by fire. They also added a grand architectural feature: a pediment above the central façade bearing the combined coats of arms of the Lorgeril and the Beynaguet de Pennautier families. A major restoration was completed in 2010, which preserved the château’s historic character and adapted it for new uses including hosting cultural events and supporting the operations of the Lorgeril vineyards.

The château’s cultural and historic value was formally recognized when it was listed as a historic monument in 1972, with its interior decoration receiving similar status in 1989. During the 2010 restoration, nearly fifteen meters of archival documents relating to the château and the wool textile factory were deposited in the departmental archives of Aude, providing important resources for understanding its economic and social history.

Remains

The Château de Pennautier is an elegant example of early 17th-century Louis XIII architectural style, noted for its balanced proportions and extensive use of large windows that open onto two distinct courtyards—one facing south and the other to the north. This dual courtyard layout was innovative at the time, providing both aesthetic appeal and practical functionality. The main south façade stretches roughly 100 meters in length, creating an imposing and harmonious frontage.

In the 1670 expansion, architect Louis Le Vau introduced two wings beside the main building: to the east, an orangery designed to shelter delicate plants during colder months, and to the west, a ballroom or music room that served as a social and cultural space. These additions enhanced both the utility and grandeur of the château.

Surrounding the château was an extensive formal garden covering over 30 hectares, laid out by André Le Nôtre, a renowned landscape architect famous for his work on the gardens at Versailles. His design featured the geometric precision and symmetry characteristic of French formal gardens of the era, integrating the natural environment into the estate’s overall aesthetic.

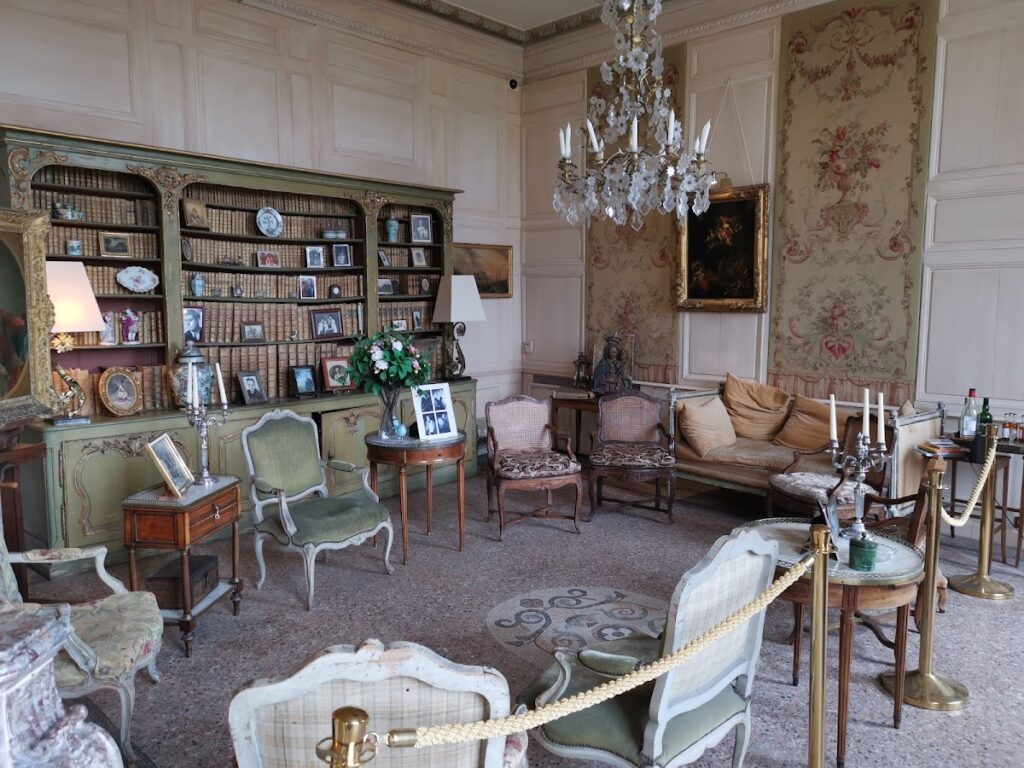

Inside the château, the “King’s chamber” preserves an exceptional suite of royal traveling furniture gifted by Louis XIII during his 1622 visit. The pieces include a canopy bed and six folding armchairs, all upholstered in fine tapestry with wool and silk fillings, providing insight into 17th-century craftsmanship and royal taste. These furnishings are now classified as historic monuments.

During the 19th century, renovations brought Italian influences indoors, including the installation of mosaic floors made of small colored tiles arranged in decorative patterns. At the same time, the gardens were redesigned in the English landscape style, characterized by a more naturalistic arrangement with winding paths and varied plantings, replacing the earlier strict formality typical of French design.

The early 20th century witnessed structural changes when a northeast wing was removed after suffering fire damage. This phase also added a large pediment above the central façade’s projection—it prominently displays the heraldic coats of arms of the Lorgeril family alongside those of the Beynaguet de Pennautier lineage, reflecting the estate’s blended heritage.

Beyond its architecture and gardens, the château maintains an extensive collection of archives connected to its historical textile manufacture. These documents, including catalogues and records related to the large wool factory once operating on the estate, offer valuable information about the industrial activities tied to the château’s history.

Together, these buildings, furnishings, gardens, and archives provide a well-preserved overview of the château’s development from the 17th century to the present day, illustrating its role as a site of aristocratic life, economic enterprise, and cultural heritage in southern France.