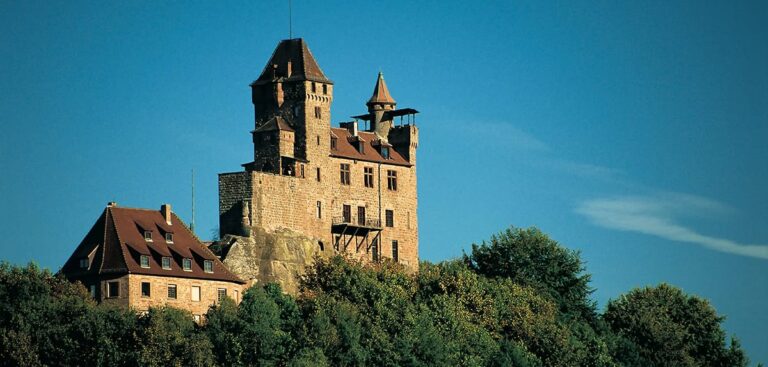

Château de Hohenbourg: A Medieval Rock Castle in Wingen, France

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.7

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.alsaceterredechateaux.com

Country: France

Civilization: Medieval European

Remains: Military

History

The Château de Hohenbourg is located in the municipality of Wingen in modern-day France. This medieval stronghold, built by local lords whose precise origins are uncertain, dates back to the mid-13th century and is characteristic of semi-troglodytic castles, incorporating natural rock formations into its structure.

The first recorded occupants were the Puller family, who later adopted the name Hohenbourg. Early in its history, the castle shared feudal overlordship with the Fleckenstein family, leading to ongoing disputes. The castle appears in historical records from 1262 as the property of Konrad and Heinrich von Hohenburg. Between 1273 and 1289, a series of conflicts erupted between the Hohenburgs and Fleckensteins, culminating in Landvogt Otto von Ochsenstein seizing nearby fortresses to quell the unrest.

Throughout the late 14th and early 15th centuries, ownership changed hands several times. In 1389, Vye von Wasigenstein handed the castle over to Elector Palatine Ruprecht I, who subsequently granted it in 1401 to Konrad Puller von Hohenburg. The mid-15th century saw further familial transfers; Wilrich II von Hohenburg gave the castle to his wife, Jutta von Schöneck, while their son Richard engaged in disputes with the Elector Palatine. These tensions led to the castle’s seizure and Richard’s execution in 1482.

By the late 15th century, the estate passed to the Sickingen family through marriage, with Swicker VIII von Sickingen acquiring it in 1475. Under Franz von Sickingen, the castle underwent significant military enhancements in 1504. Despite these efforts, it faced severe destruction in 1523 when forces allied under Elector Ludwig V, Archbishop Richard of Trier, and Landgrave Philipp I of Hesse attacked it. The Sickingens rebuilt the stronghold in the Renaissance style by 1542.

The castle’s fortunes declined during the Thirty Years’ War when Swedish troops caused heavy damage. Finally, in 1680, French forces commanded by Joseph de Montclar, acting on orders from King Louis XIV, completely destroyed the castle. Afterwards, the property remained under French control, with the Sickingen-Hohenburg family making their last claims to it in 1836. Since the 19th century, several uncoordinated archaeological excavations have taken place. The site earned recognition as a historic monument in December 1898 and saw partial restoration efforts during the 1970s.

Remains

The Château de Hohenbourg is classified as a rock castle, or Felsenburg, built partly within and upon natural rock formations on the Schlossberg at an elevation of 551 meters. The ruins are arranged around a prominent rock that likely bore a residential tower in the castle’s prime. Near this rock, a well remains visible, indicating the medieval inhabitants’ method for accessing water within the fortress.

Among the notable remnants is a horseshoe-shaped artillery bastion dating back to the late 15th or early 16th century. This defensive structure features walls ranging from approximately 3.6 to 4.6 meters thick and was pierced by two large gateways alongside two gun ports. These openings illustrate the adaptation of the castle to emerging military technologies, allowing the deployment of firearms and artillery, reflective of the period’s evolving defensive architecture.

A Renaissance-style doorway from the early 1500s survives within the site, though the portal’s stonework has suffered increasing damage due to vandalism. This entrance forms part of the castle’s fortified access, supplemented by an artillery rondel—a rounded defensive tower designed specifically to accommodate firearms and enhance protection during the early 16th-century renovations.

The castle’s layout takes full advantage of its natural setting, incorporating steep rock surfaces for natural defense and habitation. From its terrace, occupants would have enjoyed commanding views over the Northern Vosges and the neighboring Palatinate region; on clear days, visibility extended across the Upper Rhine Plain as far as Karlsruhe.

Today, the ruins remain fragmented but preserve essential features demonstrating the castle’s strategic design and phased development. Access to the site passes through forest paths managed by the Club Vosgien, leading visitors from the nearby village of Lembach to the Gimbelhof area and onwards to the castle ruins.