Castle of Castellano: A Medieval Fortress in Villa Lagarina, Italy

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.2

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.visitrovereto.it

Country: Italy

Civilization: Unclassified

Remains: Military

History

The Castle of Castellano is situated in the village of Castellano within the municipality of Villa Lagarina, Italy. Its origins trace back to the medieval period when it was constructed by local rulers in the 11th century, reflecting the region’s early feudal structures.

The earliest part of the castle, notably its tower or keep, dates to the 11th century, marking the site as a strategic stronghold overlooking the Vallagarina valley and nearby town of Rovereto. By the late 12th century, the castle served an administrative role as an episcopal gastaldia, a type of jurisdictional domain, under Gerardo, recognized as lord of Castellano. Over the following centuries, control of the castle passed through several noble families. From 1162 to 1234, the Da Beseno family held the fortress, followed by the Castelnuovo family between 1234 and 1266. The Castelbarco family then assumed control, maintaining their hold from 1266 until 1456.

A significant change took place in 1456 when Giorgio and Pietro Lodron, acting on behalf of the bishop of Trento, seized the castle from Giovanni Castelbarco. This event marked the beginning of the Lodron family’s stewardship, which lasted until 1924. Within this line, the family split into branches known as Lodron di Castellano and Lodron di Castelnuovo. The Lodronlords carried out substantial renovations during the 16th and 17th centuries, decorating key interiors such as the main hall with frescoes, adding a new portal in the 17th century, and installing a copper roof on both the keep and the attached palace building.

The castle entered a military phase during the First World War when Austro-Hungarian forces utilized it as a base. A military cableway was established to supply the site with weapons and ammunition. However, the castle endured damage caused by the shockwaves of heavy artillery fire and suffered a direct shell hit fired from Monte Zugna. After the war, its interiors were stripped of furnishings, and in 1924 the castle was sold to the Miorandi family, who remain its private owners.

The 20th century brought structural challenges to the castle. Parts of its walls partially collapsed over time, and a devastating fire erupted on New Year’s Eve between 1931 and 1932. Further damage occurred in 1944 when a major wall gave way, possibly worsened by vibrations from nearby Allied bombing raids. Despite these setbacks, a partial reconstruction took place in 1953, focusing on the site’s main hall area, allowing some parts of the castle’s perimeter to be preserved. Today, remnants of its former spreads, including long curtain walls and a guard tower, remain visible as testimony to its layered history.

Remains

The Castle of Castellano presents an irregular pentagonal layout, composed mainly of sturdy stone constructions. Its central feature is a Romanesque keep, or mastio, which sits on a rocky spur approximately 789 meters above sea level. This tower is built with rusticated stone blocks at its corners called quoins, and although only half of its original height remains, it originally rose higher, providing strong defensive advantages. The tower’s base corresponds to what was once the third floor of the adjoining palace, creating a complex vertical relationship within the castle’s structure.

Attached to the mastio on the northern corner is the palace, notable for its irregular five-sided shape. This building housed more than 35 rooms across four main floors, as well as a cellar and a large attic, all arranged around a small inner courtyard. Among its many features, the palace had a mill powered by animal force, a granary for storing grain, and an entrance hall featuring a central well. This well drew water from a rainwater cistern, demonstrating the castle’s provisions for self-sufficiency. Within the palace was also a small chapel dedicated to Saint Joseph, which was separated from a nearby loggia—a covered gallery—by a carved walnut gate, above which an Annunciation fresco was painted.

The roof structure of the palace was distinctive, with five inward-facing slopes designed both to channel rainwater efficiently and to strengthen its defenses. On its southern sides, the external walls rose impressively, measuring more than 20 meters in height. The overall shape of the castle has been likened to a traditional wine vessel known locally as a “mastela,” with the palace serving as the body and the tower as a long handle. This resemblance gave rise to the nickname “Castel Bazzom.”

Surrounding the palace and keep are two principal curtain walls—fortified retaining walls designed to protect the inner buildings. The first closely encircles the central structures atop the rocky outcrop, while a second larger wall encloses an area of approximately one hectare. This outer enclosure is now occupied by the local village cemetery. Both of these defensive walls largely survive and offer insight into the castle’s fortified footprint.

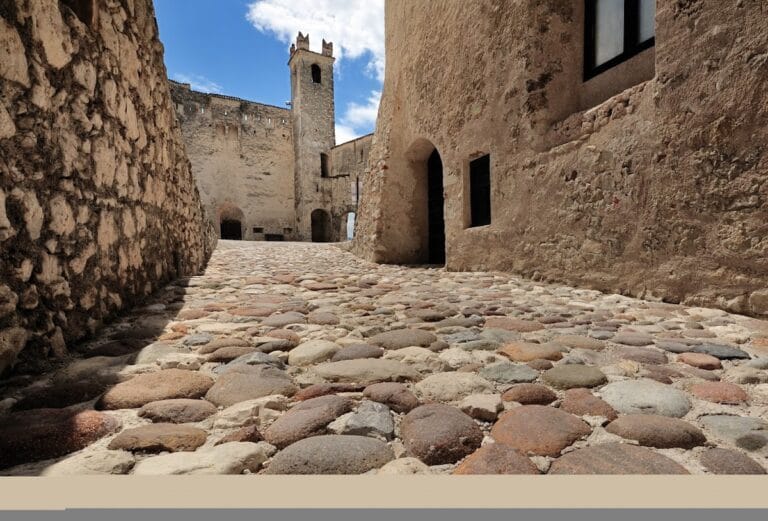

The northern approach to the castle was guarded by a semicircular curtain wall featuring a 17th-century gate, known as a portal, and a control tower equipped with a dovecote for pigeons or doves. A ramp led down from this entrance point to the village square, once protected by a drawbridge that could be raised or lowered to control access. The external walls exhibit a sloped design, called scarping, which was a common defensive tactic intended to resist the impact of or deflect early artillery fire. These walls ended by abutting the main castle structure, forming a continuous defensive line.

Some of the castle’s interior rooms were richly decorated with frescoes in the early 17th century. These paintings depicted local landscapes as well as coats of arms representing noble families connected to the site. Following the fire of 1931, these frescoes were carefully removed and are now preserved at the Rovereto Civic Museum. Historically, the castle maintained a substantial armory that contained a variety of weapons, including cannons, bombards (early cannons), swords of several sizes, and a large collection of arquebuses, which were early firearms. In 1796, some of these weapons were requisitioned for use in the defense against Napoleon’s advancing forces, while the remainder were seized by French victors thereafter.

Over time, the castle has endured several damaging events. An earthquake in 1878 caused partial structural failure, and the building suffered further collapse in 1918. The fire of 1932 destroyed much of the wooden components, leaving only the keep and a tower-shaped remnant of the palace intact. These two elements are now connected at ground level by a covered structure and the remains of the former outer wall. Despite the loss of much of its fabric, the surviving features at Castellano preserve the story of a complex medieval fortress adapted through centuries of noble residence and military use.