Castel Pergine: A Historic Fortress in Pergine Valsugana, Italy

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.4

Popularity: Medium

Official Website: www.castelpergine.it

Country: Italy

Civilization: Medieval European

Site type: Military

Remains: Castle

History

Castel Pergine stands on Colle Tegazzo, near the town of Pergine Valsugana in Italy. Its origins trace back to ancient times, possibly as a fortified settlement during the Roman or even pre-Roman era, with some scholars proposing a connection to the Rhaetian peoples who once inhabited the area. While the exact date of the castle’s initial construction remains uncertain, early medieval records first mention it in 845, suggesting it may have been founded or rebuilt by Lombard rulers. A 12th-century document refers to Odorico da Pergine and Ezzelino, indicating its early importance within local feudal networks.

During the 13th century, Castel Pergine was under the control of the Pergine lords, a family linked to major noble houses in the Trentino region. In this period, it suffered a violent episode when troops led by Ezzelino da Romano captured and set fire to the fortress, a reflection of the turbulent conflicts of the time. Later, Prince Enrico II reclaimed the castle and entrusted it to his son Adriano, who undertook measures to preserve and rebuild the stronghold. This restoration emphasized the castle’s strategic significance as a guard post regulating passage between the Veneto region and Trentino.

Following these developments, the fortress became a fiefdom of Mainardo II, Count of Tyrol. It experienced further military engagements, including attacks orchestrated by Marsilio Partenopeo with the support of the bishops of Trento and Bressanone. In 1322, the castle came under the authority of Bishop Bonaventura Gardelli of Trento, who appointed Jacopo da Carrara as its custodian to block an incursion by Duke Corrado of Teck. A dramatic event took place in 1349 when Dioniso Gardelli, the bishop’s nephew, attempted to betray the castle by handing it over to enemy forces, but Bishop Bonaventura intervened, ultimately executing his nephew to safeguard control.

The Carrara family governed Castel Pergine until 1356, after which it fell under Tyrolean possession, maintaining this status until 1531. Around the middle of the 15th century, significant reconstruction transformed the castle’s architecture, adopting the Gothic style that characterizes much of its appearance today. Later, the castle entered the jurisdiction of Bishop Bernardo Cles, followed by ownership under Baron Fortunato Madruzzo and the Wolkenstein family. Eventually, ecclesiastical authorities from Trento resumed direct management, with Antonio Giuseppe Girardi serving as the last captain from 1795 to 1805.

In the early 20th century, a German enterprise led by Julius Friedrich Lehmann acquired Castel Pergine and initiated extensive renovation plans to convert the fortress into a hotel and restaurant. These alterations were halted by authorities in 1913 to preserve the castle’s artistic qualities. Over the centuries, Castel Pergine hosted several distinguished visitors, such as Archduke Frederick known as “Tascavuota,” Emperor Maximilian I, Cardinal Bernardo Clesio, Cristoforo Madruzzo, and the Indian poet Jiddu Krishnamurti. After a period of private ownership beginning in 1956, restoration efforts revived the castle’s structure, and in 2018 stewardship passed to the nonprofit Fondazione Castel Pergine ONLUS, which continues to oversee its upkeep and cultural activities.

Remains

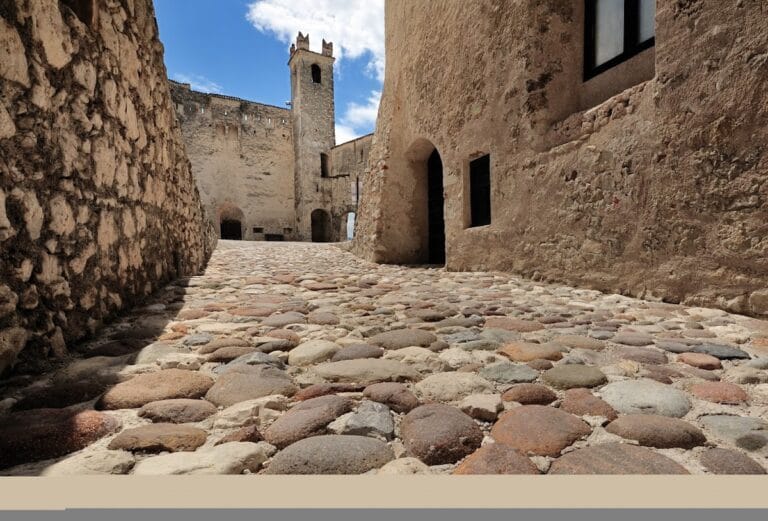

Castel Pergine is organized around a quadrangular layout situated at the summit of Colle Tegazzo, combining medieval military design with later Gothic modifications. The fortress is enclosed by robust curtain walls featuring multiple watchtowers spaced at intervals, forming a defensive ring that secures the complex along the three more exposed sides of the hill. The walls are constructed from local stone, with battlements designed for protection and observation. On the side facing the cliff, the main palace and a large tower are integrated directly into the curtain wall, creating a continuous fortified facade.

Access to the castle is controlled through a square guard tower situated on the road leading to Pergine. Historically, a drawbridge connected this tower to the entrance, although it no longer survives. To the right of this tower stands the so-called “torture tower,” a substantial cylindrical structure resting on a solid rock foundation. This tower has a wide base and is equipped with narrow openings called loopholes for archers, along with windows shaped like false crosses which contribute both to defense and architectural character.

Inside the walls, large stone spiral staircases provide vertical movement between floors, linking the entrance area, living spaces, and upper chambers. The ground level contains functional rooms including the entrance hall, kitchens, and cellars, as well as access to an enclosed garden visible only from within the fortress itself. Above this, the first floor houses ceremonial and religious spaces such as the throne room and the chapel dedicated to Sant’Andrea, alongside modern reinterpretations like a bar and restaurant area.

Further up, the second floor contains several notable rooms named for their historical or decorative significance. These include the Sala del Balconcino, Sala del Vescovo, Sala della Stufa Verde, Sala del Principe, and Sala della Dama Bianca. These rooms showcase exhibits related to the region’s fruit cultivation, photographic portrayals of the Valsugana valley, and displays of local plants and historical documents linked to the castle.

The external fortifications also incorporate two ravelins, which are triangular defensive works positioned between the inner and outer curtain walls to enhance protection. From the guard tower, rough steps carved directly into the rock ascend to the Gothic palace, a structure distinguished by four facades lacking overhanging eaves and bearing the darkened surface typical of centuries-old stone. The palace’s north facade features rows of windows arranged symmetrically and a characteristic split window accompanying a Gothic-style entrance doorway. At the northeast corner, a semicylindrical bastion with a slanting base nestles into the rock face overseeing the ravine.

Additional defensive elements include battlements near the Madonna tower, overlooking an open space known locally as the “prison of the knives.” This area likely served as an isolated enclosure within the castle grounds. Another notable feature is the “prison of the drop,” a small cell designed for a form of torture where drops of water fall steadily on the captive’s head, intended to cause psychological distress.

The castle’s west facade is marked by two long, narrow balconies with cross-shaped windows, enhancing the defensive outlook, while the south facade faces the castle’s lawn with barred windows that emphasize security. On the ravine side, the angular bastion and an ancient square tower rise prominently, the base composed of rusticated stone blocks set firmly into the rocky terrain.

Today, the castle’s core areas spanning the ground to the second floor are accessible to the public, with guided tours offered seasonally. The structure remains a well-preserved example of medieval fortification carefully layered with Gothic architectural influences and enriched by centuries of history and transformation.