Caesarea Philippi: An Ancient Religious and Administrative Center at Banias

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.6

Popularity: Very Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Country: Israel

Civilization: Byzantine, Crusader, Early Islamic, Greek, Roman

Remains: City

Context

Caesarea Philippi is situated at the southwestern base of Mount Hermon, a prominent massif in the Levant. The site occupies a limestone plateau characterized by cliffs and natural terraces, positioned directly above the Banias spring, a perennial karst water source that contributes to the headwaters of the Jordan River. This abundant spring shaped both the settlement’s location and its religious significance throughout antiquity.

Archaeological evidence indicates occupation from the Iron Age onward, with material culture and architectural remains documenting successive phases of development. During the Hellenistic period, the site, then known as Paneas, became a cult center dedicated to the Greek god Pan, replacing earlier Semitic religious traditions linked to the spring. In the early first century CE, Herod Philip II refounded the city as Caesarea Philippi, initiating urban expansion and Roman-style civic institutions. Subsequent Roman and Byzantine layers reveal continued urbanization, Christian ecclesiastical presence, and evolving religious practices. Early Islamic and medieval remains attest to the site’s enduring, though fluctuating, regional role.

Modern archaeological investigations, beginning in the early twentieth century, have uncovered inscriptions, coins, pottery, and architectural features that corroborate historical accounts and illuminate cultic activities. The site’s ruins are preserved within the Banias Nature Reserve, where natural vegetation, water dynamics, and later human interventions influence the state of preservation and archaeological accessibility.

History

Caesarea Philippi’s historical trajectory reflects its strategic location and rich water resources, which fostered religious, administrative, and military significance across millennia. Initially a pagan sanctuary, the site evolved through Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, early Islamic, Crusader, and Ottoman periods, each leaving distinct cultural and architectural imprints. Its control shifted in accordance with broader regional power struggles, while its religious identity transformed from a center of Pan worship to a Christian bishopric and later a contested frontier town.

Hellenistic Period (3rd–2nd century BCE)

Following the conquests of Alexander the Great, the site emerged as Paneas, named after the Greek deity Pan. The Ptolemaic dynasty established a cult sanctuary here in the third century BCE, supplanting earlier Semitic deities associated with the spring, such as Baal Hermon and Baal Gad. The spring issued from a large natural cave carved into the cliff face, which became the focal point for ritual activity. Sacrifices were cast into the water-filled cave as offerings to Pan, reflecting a syncretism of local and Hellenistic religious traditions.

The sanctuary complex included an open-air precinct with a temple at the cave’s entrance, ritual courtyards, and niches hewn into the cliff to house statues of Pan, Echo (a mountain nymph), and Hermes (Pan’s father). The Battle of Panium (circa 200–198 BCE), fought nearby between Seleucid and Ptolemaic forces, resulted in Seleucid dominance, who further developed the cult site. Inscriptions dated to 87 BCE and coins depicting statues in the cliff niches confirm the religious prominence of Pan worship. The site’s name evolved linguistically from Paneas to Banias in Arabic, preserving its Greek heritage.

Roman Conquest and Herodian Administration (1st century BCE – 1st century CE)

In 20 BCE, following the death of Zenodorus, the Panion region including Paneas was incorporated into the Herodian Kingdom of Judea under Roman client rule. Emperor Augustus granted the territory to Herod the Great, who erected a white marble temple dedicated to Augustus near the spring, symbolizing the imperial cult’s integration. Around 3 BCE, Herod Philip II refounded the city as Caesarea Philippi, establishing it as his administrative capital and distinguishing it from other cities named Caesarea.

After Philip’s death in 34 CE, the city briefly reverted to direct Roman provincial administration before passing to Herod Agrippa I and subsequently to Agrippa II. Agrippa II expanded the urban fabric and renamed the city Neronias in 61 CE in honor of Emperor Nero, though this appellation was abandoned by 68 CE. The city is referenced in the Christian Gospels as the site where Jesus affirmed Peter’s messianic confession, marking its importance in early Christian tradition. During the Jewish revolt, Titus staged gladiatorial games here, where Jewish prisoners fought to the death. Archaeological remains from this period include a large Roman-style palace, a main north-south street (cardo), and a monumental columned building near the spring.

Imperial Roman and Byzantine Period (1st–7th century CE)

Following Agrippa II’s death around 92 CE, Caesarea Philippi reverted to direct Roman provincial control within the province of Syria. The city continued to be known as Paneas or Caesarea Paneas in late Roman and Byzantine sources. The fourth century CE witnessed the spread of Christianity, with Caesarea Philippi becoming a bishopric seat in the province of Phoenicia. Archaeological excavations have revealed two churches: a large basilica constructed over the Roman columned building in the city center, and a smaller chapel adjacent to the cave sanctuary.

Pagan worship persisted intermittently during this period. Emperor Julian the Apostate briefly reinstated pagan rites in 361 CE, replacing Christian symbols with pagan ones, though this restoration was short-lived. The sacred precinct encompassed a Roman-style triclinium-nymphaeum complex and open-air temples dedicated to Pan and Zeus. Ritual sacrifices continued, with offerings cast into the spring and believed accepted if they disappeared beneath the water’s surface. An earthquake shifted the spring’s source from the cave mouth to the base of the cliff, diminishing its flow. A seventh-century altar dedicated to Pan Heliopolitanos found within a church indicates residual pagan elements within Christian contexts. A hoard of 44 gold coins from the early seventh century CE, minted under Byzantine emperors Phocas and Heraclius, dates to the period of the Arab conquest.

Early Muslim Period (7th–10th century CE)

In 635 CE, Paneas surrendered to Muslim forces led by Khalid ibn al-Walid under favorable terms. The city briefly served as a Byzantine staging post before the decisive Battle of Yarmouk in 636 CE. Following the Muslim conquest, the city’s population and economic activity declined markedly, though it remained the administrative center of the al-Djawlan district within the military province (jund) of Dimashq (Damascus). The tenth-century geographer al-Muqaddasi described Banias as a prosperous grain-producing area, indicating some economic recovery.

The city hosted diverse religious communities, including Muslims, Christians, and Jews. Archaeological evidence attests to a synagogue later converted into a mosque during the eleventh century. Banias was contested by various powers, including the Fatimids, Bedouin Qarmatians, and local dynasts, reflecting ongoing political instability. A notable inscription from 1226 CE records rebuilding efforts of the fortress by the Ayyubid ruler al-‘Aziz ‘Uthman.

Crusader and Ayyubid Period (12th–13th century CE)

During the Crusader and Ayyubid periods, Banias functioned as a militarized frontier town. Initially held by the Ismaili sect (Assassins) from 1126 to 1129, it was transferred to Crusader control following their expulsion from Damascus. The city changed hands multiple times: Muslim forces recaptured it in 1132, but it returned to Crusader control in 1140 through alliances with Damascus rulers. Banias became the fiefdom of Humphrey II of Toron and a key military and administrative center for the Crusaders and the Knights Hospitaller.

The city endured sieges by Nūr ad-Din in 1157 and 1164, with the latter ending Crusader control. The Crusaders constructed the nearby castle of Hunin (Château Neuf) to protect trade routes between Damascus and Tyre. Saladin used Banias as a military base in the late twelfth century, with forces from here participating in major battles such as Cresson and Hattin. A strong earthquake in 1202 damaged the city and fortress, which were subsequently rebuilt by Ayyubid rulers. During the Fifth Crusade, Banias was raided but remained under Muslim control. The fortress was dismantled in 1219 by Al-Mu’azzam Isa to prevent Crusader reoccupation but was rebuilt by al-‘Aziz ‘Uthman in 1227, who also constructed the nearby Nimrod’s Castle (Qal’at al-Subayba). Under the Mamluks, Banias served as an administrative center subordinate to Damascus.

Ottoman Period (16th–19th century CE)

Under Ottoman rule, Banias declined to a small agricultural village and customs point on the road to Damascus. Archaeological remains from this period are limited. The population was predominantly Muslim, including Shia Metawali communities numbering between 350 and 500 in the nineteenth century. The village was surrounded by gardens and orchards irrigated by aqueducts drawing water from the Banias spring. Evidence suggests local production of Ottoman-style clay pipes. European travelers of the nineteenth century described Banias as a modest settlement with visible ruins of the ancient city and fortress.

20th Century and Modern Period

Following World War I, the Banias spring and village fell within the French Mandate of Syria, with the international boundary set just south of the spring, leaving it in Syrian territory. The area’s abundant water resources made it strategically important. During the 1948 Arab-Israeli War and subsequent armistice agreements, the Banias spring remained under Syrian control, while the Banias River flowed through a demilitarized zone into Israel. In the 1950s and 1960s, Syria attempted to divert the Banias River to reduce water flow into Israel, leading to military confrontations.

During the Six-Day War in 1967, Israeli forces captured Banias; the local Syrian population fled, and much of the village was destroyed, sparing only the mosque, church, and shrines. In 1977, Israel declared the Banias area a nature reserve, encompassing the springs, archaeological site, and waterfall.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Hellenistic Period (3rd–2nd century BCE)

During the Hellenistic era, Paneas functioned primarily as a religious sanctuary dedicated to Pan, attracting Greek settlers and local Semitic populations. The social structure included priests managing the sanctuary, artisans producing cultic statues and ritual objects, and farmers cultivating the fertile limestone plateau nourished by the Banias spring. Inscriptions attest to organized religious leadership overseeing festivals and rites.

Economic activities centered on agriculture and religious tourism. The sanctuary precinct, with its temple and open-air courtyards, served as the locus for ritual sacrifices cast into the spring cave. Domestic architecture likely consisted of modest stone houses, with wealthier inhabitants possibly decorating interiors with painted plaster and mosaics, as suggested by parallels at nearby Hellenistic sites. The site’s position on routes ascending Mount Hermon facilitated trade and the circulation of coins and pottery.

Roman Conquest and Herodian Administration (1st century BCE – 1st century CE)

The Roman annexation and Herodian administration transformed Paneas into Caesarea Philippi, an urban center with a diverse population including Roman officials, Herodian elites, local Semitic peoples, and Jewish communities. Civic magistrates and priests of the imperial cult are documented through inscriptions and coinage, indicating a structured municipal government.

Economic life expanded with monumental construction, including a marble temple to Augustus and a large palace complex. Agriculture remained vital, with olive oil and grain production supported by irrigation from the Banias spring. Urban planning is evidenced by a paved main street (cardo) and colonnaded public buildings. Domestic dwellings ranged from simple homes to elaborately decorated residences featuring mosaics and painted walls.

Markets likely offered imported luxury goods transported via regional caravan routes. Religious practices combined imperial cult worship, pagan rites to Pan, and emerging Christian communities, the latter gaining prominence due to the city’s mention in the Gospels. Gladiatorial games under Titus reflect integration into Roman imperial culture.

Imperial Roman and Byzantine Period (1st–7th century CE)

Following Agrippa II’s death, Caesarea Philippi reverted to Roman provincial administration and gradually Christianized, becoming a bishopric in Phoenicia. The population comprised Roman citizens, Christian clergy, local peasants, and residual pagan worshippers. Social stratification included ecclesiastical elites and urban residents. Two churches, a large basilica and a chapel near the cave sanctuary, reflect the growing Christian community.

Agriculture remained the economic mainstay, with grain and olives cultivated using water from the spring, though an earthquake reduced its flow. Domestic interiors featured mosaic floors and painted walls typical of late antique urban homes. Markets supplied local and imported goods, connected by roads to Damascus and coastal cities. Religious life was dominated by Christianity, though pagan rituals persisted intermittently, as evidenced by Emperor Julian’s brief restoration of pagan rites and a seventh-century altar to Pan Heliopolitanos within a church. The sacred precinct combined Christian and pagan elements, illustrating religious syncretism. The city retained administrative and ecclesiastical importance.

Early Muslim Period (7th–10th century CE)

The Muslim conquest precipitated a decline in urban vitality, with population reduction and economic contraction. Banias became the administrative center of the al-Djawlan district within the jund of Dimashq. The population was religiously diverse, including Muslims, Christians, and Jews, adapting to new governance under Islamic rule.

Agriculture, particularly grain production, remained central, as noted by al-Muqaddasi. Archaeological evidence of a synagogue converted into a mosque indicates religious transformation and coexistence.

Remains

Architectural Features

The archaeological remains at Caesarea Philippi span from the Iron Age through the medieval period, with a concentration of structures from the Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine eras. The site occupies a limestone plateau with natural terraces and cliffs that influenced its urban layout. At its height, the city covered approximately 73 hectares, with the core situated south of the sacred precinct around the Banias spring. Construction techniques include finely cut ashlar masonry and local limestone blocks, with Roman concrete (opus caementicium) employed in later public buildings. The urban fabric comprises religious, residential, and civic structures arranged along a principal north-south street (cardo) and subsidiary roads. Fortifications and military architecture are primarily associated with the Crusader and Mamluk periods. Water management infrastructure, including aqueducts and channels, conveyed spring water to urban quarters. Vegetation growth and water flow have affected preservation, with some ruins partially buried or eroded.

Key Buildings and Structures

Sacred Cave and Spring of Pan

The Banias spring originally emerged from a large natural cave carved into a sheer cliff face, forming the center of pagan worship from the third century BCE onward. This cave and spring constituted a temenos (sacred precinct) that included a temple at the cave’s entrance, ritual courtyards, and a series of niches hewn into the cliff face. These niches housed statues of deities such as Pan, Echo (Pan’s consort), and Hermes (Pan’s father). A four-line Greek inscription dated to 87 BCE was found at the base of one niche, mentioning Pan and Echo. Sacrifices were cast into the water-filled cave as offerings. An earthquake in late antiquity shifted the spring’s source from the cave mouth to the base of the terrace, reducing its flow. The sanctuary precinct occupies an elevated natural terrace approximately 80 meters long along the cliff, overlooking the northern city area. The site remained a religious center through the Roman and Byzantine periods, with ritual activity continuing into the fourth century CE.

Temple of Pan and Sanctuary Complex

Constructed in the third century BCE by the Ptolemaic rulers, the cult center dedicated to Pan included an open-air sanctuary adjacent to the water source exiting the cave. During the second and third centuries BCE, additional temples and open cult complexes dedicated to Pan and Zeus were built on the terrace below the cliff east of the cave. These limestone structures featured ritual courtyards and were integrated with the water-filled cave, which formed part of the cultic space. The sanctuary’s elevated position provided a commanding view over the northern part of the city.

Palace of Agrippa II

Located in the city center, the palace complex dates to the mid-first century CE and is attributed to King Agrippa II. The structure is extensive and features mosaic floors and elaborate architectural details. It includes multiple rooms arranged around courtyards, constructed with ashlar masonry and Roman concrete. After Agrippa II’s death around 92 CE, the palace was repurposed as a public bathhouse, with modifications such as heated rooms (caldaria) and water channels added. The palace played a central role in the urban fabric during the late Herodian period.

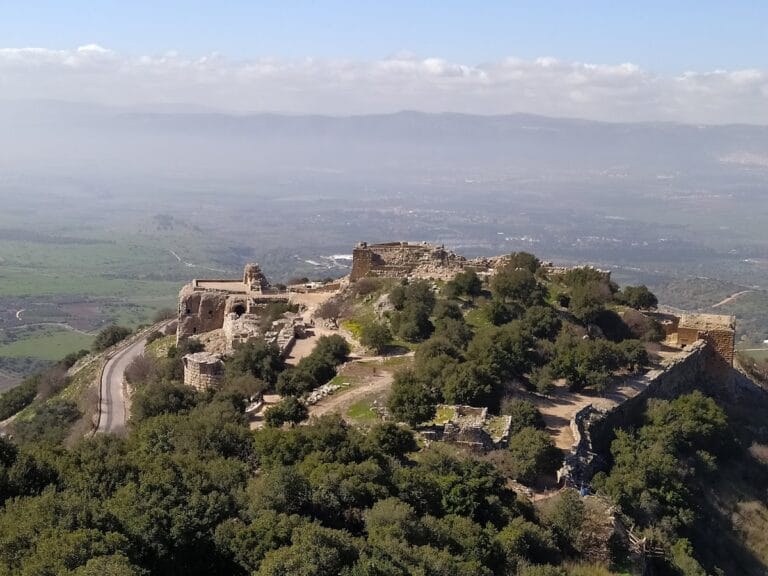

City Walls and Fortifications

The city was enclosed by defensive walls, though detailed measurements and construction phases remain partially undocumented. During the Crusader period, a strong castle known as Belinas was built in Banias to protect the trade route between Damascus and Tyre. The Crusader fortress at Hunin (Château Neuf), constructed in 1107 overlooking Banias, served as a military stronghold. The fortress was dismantled in 1219 by Al-Mu’azzam Isa to prevent Crusader reoccupation but was rebuilt in the 13th century by Ayyubid ruler al-‘Aziz ‘Uthman and later by Mamluk Sultan Baibars. The surviving fortress ruins visible today mainly date from the 13th century Mamluk period and include thick stone walls, towers, and gate structures.

Churches and Christian Buildings

Two Byzantine churches have been excavated at Caesarea Philippi. A large basilica, constructed in the fourth or fifth century CE, is located in the city center and was built over the Roman colonnaded building near the spring. This basilica features a nave and aisles, with remnants of mosaic flooring and stone columns. A smaller church or chapel lies adjacent to the cave sanctuary, possibly housing relics or fragments of a bronze statue linked to New Testament traditions. Christian symbols replaced pagan ones briefly during Emperor Julian’s reign in 361 CE, but pagan worship was restored for a short period before Christianity reasserted dominance. The smaller church’s remains include stone foundations and wall fragments.

Burial Sites

Numerous tombs and burial caves are cut into the rock west and south of the city. These funerary sites date from the second to fifth centuries CE and conform to Roman burial customs by being located outside the city walls. The tombs vary in size and complexity, including rock-cut chambers and simple burial niches. Some contain funerary inscriptions and grave goods, though many are fragmentary due to erosion and later disturbances.

Water Infrastructure

The city’s water supply was abundant, primarily fed by the Banias spring and additional springs east of the urban area. Aqueducts and channels constructed of stone and masonry conveyed water into the city, supplying public buildings, the palace, and residential quarters. The original strong flow of the spring diminished after an earthquake shifted its source from the cave mouth to the cliff base. Remains of aqueducts and water channels are visible in several locations, demonstrating the city’s hydraulic engineering.

Other Remains

Surface surveys and excavations have identified additional Hellenistic and Roman-period structures, including workshops, domestic buildings, and storage facilities. Architectural fragments such as column drums, capitals, and ashlar blocks are scattered across the site. Ceramic debris, coins, and inscriptions related to the cult of Pan and city donors have been recovered. These remains are often fragmentary and partially buried but contribute to understanding the city’s layout and functions.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations at Caesarea Philippi have uncovered a variety of artifacts spanning from the Iron Age through the early Islamic period. Pottery includes locally produced and imported amphorae and tableware from Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine contexts. Numerous inscriptions in Greek and Latin have been found, including dedicatory texts to Pan, Echo, and Hermes, as well as Christian inscriptions from the Byzantine period. Coins recovered range from Hellenistic issues to Roman imperial and Byzantine emperors such as Phocas and Heraclius. A notable hoard of 44 pure gold coins dating to the early seventh century CE was discovered in 2022, reflecting the transition from Byzantine to early Islamic rule.

Religious artifacts include statuettes, altars, and ritual vessels associated with the sanctuary of Pan.