Breno Castle: A Medieval Fortress in Italy

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.5

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.comune.breno.bs.it

Country: Italy

Civilization: Unclassified

Remains: Military

History

Breno Castle stands on a prominent hill in the town of Breno, Italy, built and developed by medieval communities during the Middle Ages. The site’s history begins far earlier, with human presence dating back to prehistoric times.

Archaeological evidence points to human activity during the late Epigravettian period, as indicated by flint flakes uncovered on the hill. Later, during the Neolithic era, inhabitants constructed a trapezoidal dwelling fitted against natural rock formations using wattle and daub walls—a technique involving woven branches covered with mud—that was characteristic of the Val Camonica region. Additional finds nearby, including tools, pottery, and two graves, belong to the so-called Breno culture. Despite some traces of habitation during the Copper Age, the area appears to have been abandoned during Roman times, possibly due to its proximity to the established Roman town called Civitas Camunorum.

The earliest medieval structure on the site was a chapel dedicated to Saint Michael the Archangel, a figure revered by the Lombards as a protector. This chapel dates to the 9th century. Archaeological digs near the chapel revealed five graves, one belonging to a child. By the 12th century, the chapel had been expanded into a Romanesque church, but it was later torn down to make way for the castle’s enlargement, with only its foundations surviving today.

From the 12th century onward, civil constructions began to shape the medieval complex. Among these was a large two-story palatium—likely the residence of the Ronchi family, a Guelph-aligned noble lineage—and an adjacent tower standing around 20 meters tall, originally decorated with battlements reflecting the Guelph faction’s style. A casatorre, a fortified residential tower typical in northern Italy, was also part of the complex. By the late 13th century, the whole hill was enclosed by defensive walls, accessed through a gate tower.

During the transition of control to the Milanese lords between 1250 and 1300, the castle underwent military modifications. The originally Guelph battlements were replaced with Ghibelline-style battlements, reflecting the new rulers’ political allegiance, and the palatial buildings were converted into military strongholds.

In the following century, from about 1350 to 1450, Breno Castle became a focal point of violent conflict between the Venetian and Milanese powers vying for control of the surrounding valley. Archaeological discoveries include a mass grave containing mutilated bodies dating to this turbulent period, testifying to the severity of the clashes.

In 1421, the famed condottiero Francesco Bussone, known as Carmagnola, seized the castle on behalf of the Visconti family, ousting Pandolfo III Malatesta’s forces. After the Battle of Maclodio in 1427, control shifted to Venice, with the castle placed under the command of Giacomo Barbarigo. Later, in 1438, the castle withstood a six-month siege led by Pietro Visconti. The siege ended with relief provided by troops under Pietro Avogadro, where defenders included members of the Ronchi family.

A significant siege in 1453 highlighted the castle’s strategic importance. Defended by Pietro Contarini, Captain of the Valley, castellan Nicolò Rizzi, Decio Avogadro, Pasino Leoni, and the Ronchi family members, the fortress faced an assault supported by the pro-Milanese Federici family. Francesco Sforza then sent Bartolomeo Colleoni with 1,500 men and artillery. This siege marked the first documented use of firearms in the Val Camonica, ultimately compelling the castle’s surrender.

The 1454 Peace of Lodi brought a lasting end to the local conflicts between Venice and Milan. As part of the peace terms, Brescia and the Camonica valley, including Breno, came under Venetian rule. Venice ordered the destruction of almost all castle fortifications across the valley to consolidate power but spared Breno Castle, designating it as the seat of the local Venetian regiment. This regiment also controlled nearby castles in Cimbergo and Lozio, which were held by the Lodrone and Nobili families, notable Venetian allies.

During the Venetian period, the castle’s southern defenses were significantly altered to withstand the evolving nature of warfare. These curvilinear fortifications, designed without sharp corners, aimed to better resist cannon fire and other artillery.

The castle’s military importance declined after briefly falling to French forces in 1516. By 1518, the garrison had been reduced to only six men. In the second half of the 16th century, the castle was reported as uninhabited, coinciding with the relocation of valley administrative officials to the nearby town. The formal transfer of the castle was officially recorded on April 16, 1598, marking the end of its active administrative role.

Remains

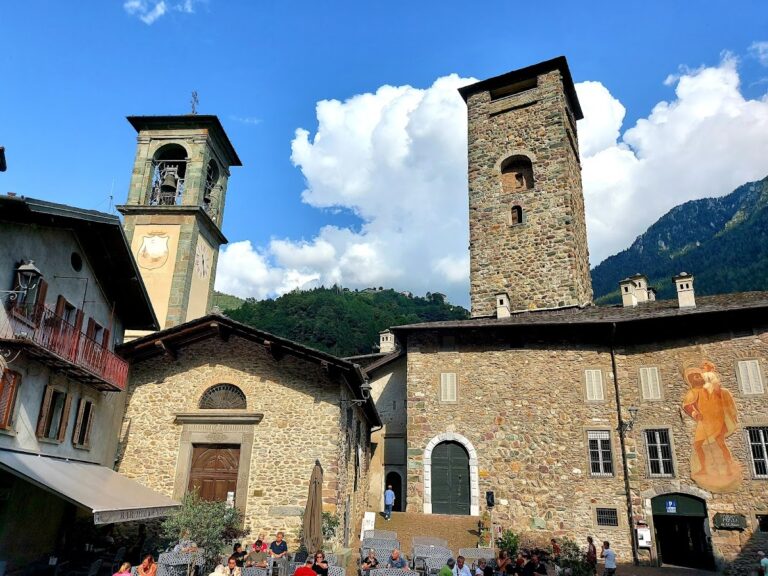

Breno Castle occupies a hilltop area of just over half a hectare, rising approximately 120 meters above the surrounding town. The structure’s layout preserves layers of its long history, integrating prehistoric and medieval remains within its bounds.

Among the earliest archaeological features is the site of a trapezoidal Neolithic dwelling measuring about five meters in width. This house was constructed against natural rock formations, a method offering natural support and protection. Its walls were built using wattle and daub—woven wooden strips reinforced and coated with mud, typical of traditional Val Camonica construction techniques.

The most ancient medieval remains include the foundations of the chapel devoted to Saint Michael the Archangel. Initially built in the 9th century and subsequently expanded into a Romanesque church around the 12th century, the chapel was dismantled during later castle enlargements. Though only its base survives, nearby excavations uncovered five graves, including a child’s tomb, linking the chapel to earlier spiritual functions at the site.

The medieval complex once featured a large two-story palatium, the remains of which are now destroyed. This building likely housed the influential Ronchi family. Adjacent to this was a tower rising around 20 meters, known for its original Guelph-style battlements—decorative crenellations reflecting the political faction of the time. A casatorre, a fortified residential tower typical of medieval Italian castles, is also part of the surviving layout.

By the late 13th century, the hill was surrounded by defensive walls accessible via a gate tower, enclosing the heart of the complex. Under Milanese control, the military architecture changed, with battlements transformed to the Ghibelline style, characterized by swallowtail merlons, which symbolized allegiance to the emperor.

During the Venetian period, the castle’s southern defenses were rebuilt with rounded, flowing walls that lacked sharp corners. This design aimed to better absorb and deflect the impact of cannonballs and other artillery, reflecting advancements in military technology.

The site includes the main tower, often called the Torre Maggiore or Canevali, standing prominently within the castle. Alongside it lies an inner courtyard, offering a central open space within the fortifications. Photographic records capture these key features, documenting the castle’s medieval military character.

In addition to the chapel’s graves, a somber archaeological find is the mass grave containing mutilated bodies tied to the violent Venetian-Milanese conflicts of the 14th and 15th centuries, providing evidence of the castle’s contested past.

Surrounding the complex, various prehistoric tools and pottery shards connected to the Breno culture have been discovered, creating a rich archaeological tapestry that spans thousands of years of human occupation at this strategic and enduring site.