Blaundus: An Ancient Macedonian and Roman City in Turkey

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.5

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.usak.bel.tr

Country: Turkey

Civilization: Greek, Roman

Remains: City

History

Blaundus Ancient City is located in the municipality of Ulubey in modern-day Turkey and was originally established by Macedonian settlers. Founded in 334 BCE, it emerged during the Hellenistic period near the historical border region between Lydia and Phrygia in Asia Minor.

The city began as a Greek settlement and later became a military outpost under the Pergamon Kingdom. In 189 BCE, Blaundus came under Roman authority, maintaining its significance through both the Roman and Byzantine eras. Throughout these periods, it played a notable role as an ecclesiastical center, acting as a subordinate bishopric to the Metropolitan Archdiocese of Sardes and falling under the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. In the 5th century AD, its religious administration was associated with the diocese center at Sebaste.

The name of the city appears in various ancient sources. While coins from the area bear the name Mlaundus, Roman-period Greek inscriptions show it as Blaundus. An inscription discovered in 1845 by W. J. Hamilton confirmed the city’s Macedonian origins by mentioning the Blaundians as “Blaundeon Makedonan,” meaning Macedonian Blaundians.

Blaundus has recorded participation in significant religious councils through its bishops. Notable clerics include Phoebus, who was active around 359 AD but was removed from his position due to opposition to the Arian Christian doctrine; Elijah or Helias, who attended the Council of Chalcedon circa 451 AD; and Onesiphorus, who signed a letter sent to Emperor Leo in 458 AD. The last known historical references to the city date from the 12th century.

Archaeological findings have traced human activity in the area back to the early 2nd millennium BCE, connecting it with ancient Assyrian trade colonies. During the late Roman period and continuing into the 4th century AD, Blaundus resumed issuing its own coinage. It is also likely that Roman veterans settled in the city following the various civil wars of the Roman Empire, contributing to its continued development. A significant phase of urban strengthening occurred in the 4th century CE when large fortifications were constructed, encompassing about half of the city’s imperial-era footprint. Despite these defensive works, evidence suggests Blaundus sustained a prosperous residential community into the 6th century, before later urban decline and the reuse of building materials marked changing times.

Remains

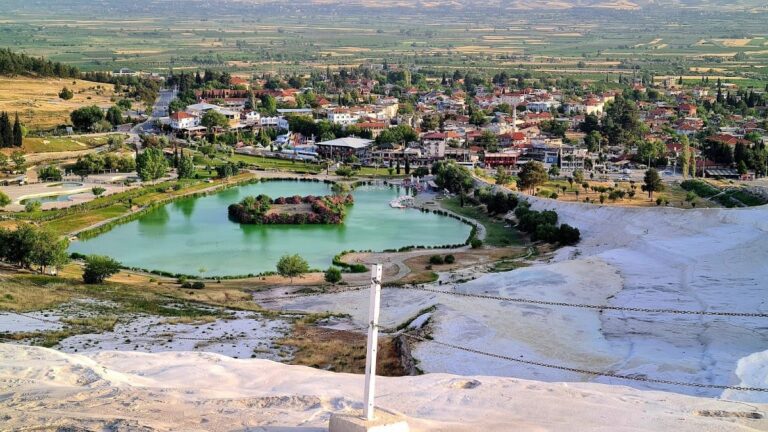

Blaundus occupies a flat promontory shaped naturally by deep, steep valleys on three sides, creating a peninsula-like setting. The city’s defensive structures reflect its strategic location and historical importance. The main entrance lies to the north, once marked by a gate flanked by two substantial towers. Although these towers and the arch spanning the gate have collapsed, remnants of the city walls survive, including 14 arches, with one arch notably remaining intact.

Outside the city walls, on a sloping terrain, lie the remains of an ancient theater. Some rows of seating still remain visible, indicating where spectators once gathered for performances or public events. Within Blaundus itself, traces of buildings built in the Ionic architectural order suggest the presence of temples or civic structures. Among these are several temples and other buildings of various sizes whose stone masonry has endured.

In the northern quarter of the city, an extensive necropolis reveals the burial practices of its inhabitants. Additionally, rock-carved tombs are found in the valley to the east, illustrating diverse funerary traditions in the broader landscape surrounding Blaundus.

Water was supplied to the city by a nearby stream flowing through a canyon approximately 100 meters deep, demonstrating the importance of natural features for urban necessities.

Further archaeological investigation by the German Archaeological Institute uncovered a stadium and additional temple complexes, adding to the picture of a city with religious, social, and recreational infrastructure.

The 4th-century fortifications significantly reduced the area enclosed by the city’s walls, yet within these defenses, luxurious residential buildings flourished, indicating that economic and social life remained vibrant during this period. By the 6th century, however, the urban fabric became more fragmented. Many existing structures were partially dismantled, and the recovered materials, known as spolia, were reused in later building projects, reflecting evolving urban dynamics and resource use.