Baia: A Roman Coastal Resort in the Phlegraean Fields of Italy

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.6

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: pafleg.cultura.gov.it

Country: Italy

Civilization: Byzantine, Roman

Remains: Burial, City, Civic, Domestic, Economic, Entertainment, Infrastructure, Military, Religious, Sanitation

Context

Baia is situated on a coastal promontory along the northwestern shore of the Gulf of Naples, within the modern municipality of Bacoli in Italy’s Campania region. The site lies within the geologically active Phlegraean Fields, an area characterized by volcanic terrain and natural thermal springs. Its elevated position overlooking the Tyrrhenian Sea provided strategic access to maritime routes and facilitated its development as a seaside retreat in antiquity. The surrounding landscape includes volcanic tuff formations and fertile soils shaped by past eruptions, which influenced settlement patterns and construction techniques.

Archaeological investigations have established that Baia was continuously occupied from the late Roman Republic through the Imperial period, with its most intensive development occurring between the 1st century BCE and the 4th century CE. The site’s thermal resources and coastal location made it a favored destination for elite leisure and residential purposes. Over time, volcanic activity and bradyseismic ground movements contributed to the partial submergence and decline of the settlement, as documented by stratigraphic evidence and historical accounts. Excavations, initiated in the 18th century and ongoing in various phases, have uncovered well-preserved remains of villas, bath complexes, and harbor installations, many protected by volcanic ash deposits. Current conservation efforts aim to stabilize these ruins and facilitate scholarly research, with portions of Baia accessible as an archaeological park.

History

Baia’s historical trajectory illustrates its evolution from a modest coastal locality into a prominent resort favored by Roman aristocracy. Its position within the volcanically active Phlegraean Fields shaped both its urban development and eventual decline. The site’s prominence peaked during the late Republic and early Imperial eras, reflecting broader political and social transformations in Campania and the Roman world. Subsequent volcanic disturbances and shifting imperial structures contributed to its gradual abandonment in late antiquity.

Roman Republican Period

Following the Roman conquest of Campania during the Samnite Wars and the Social War, the region was integrated into the Roman state as a vital agricultural and recreational zone. Baia appears in the archaeological record from this period as a small settlement, primarily exploiting its natural thermal springs. While no significant military or political events are directly associated with Baia during the Republic, it functioned within the administrative framework of Roman Campania. The settlement’s modest scale and limited infrastructure suggest a community engaged in local resource use rather than broader civic or military roles.

Roman Imperial Period (1st century BCE – 4th century CE)

The establishment of the Roman Empire under Augustus marked a significant transformation for Baia. The Gulf of Naples region became a preferred retreat for Rome’s elite, and Baia developed into a luxurious resort area. Archaeological evidence documents extensive villa construction and sophisticated thermal complexes that harnessed the geothermal activity of the Phlegraean Fields. Baia was incorporated into the imperial territory of Italia, enjoying direct imperial patronage rather than provincial administration.

Although Baia was not a military site, its proximity to Naples and key maritime routes underscored its strategic coastal position. Literary sources from the period reference Baia as a favored destination for emperors and senators, highlighting its social prestige. Notably, several large vaulted structures, traditionally called temples—such as those dedicated to Diana, Mercury, and Venus—have been identified through archaeological study as thermal bath buildings rather than religious sanctuaries. The so-called Temple of Diana featured a large ogival dome designed to collect geothermal vapors and was adorned with marble friezes depicting hunting scenes. The circular Temple of Mercury functioned as a cold bath (frigidarium) with a vaulted ceiling and central oculus, constructed using wedge-shaped tuff blocks. The octagonal Temple of Venus was sunken approximately three meters below ground level, with lowered-arch windows and an internal gallery overlooking a pool. The Villa dell’ambulatio, arranged on terraces facing the sea, connected via staircases to the Mercury sector, exemplifies the site’s architectural complexity. The Temple of Sosandra, named after a statue discovered in 1953 and now housed in the National Museum of Naples, contains notable frescoes depicting female figures and a satyr holding a thyrsus. Additionally, the submerged nymphaeum of Emperor Claudius formed part of the complex, with sculptural elements relocated to the Archaeological Museum of the Campi Flegrei in the Aragonese Castle. These findings collectively attest to Baia’s role as a high-status leisure center with advanced architectural and decorative programs.

During the 3rd and 4th centuries CE, Baia remained occupied but exhibited signs of decline. The administrative reforms of Diocletian reorganized Campania into the province of Campania et Samnium, yet Baia’s prominence diminished. Archaeological strata reveal reduced construction activity and partial abandonment, likely influenced by increased seismic and volcanic disturbances. This decline paralleled wider regional and imperial transformations as central authority weakened in the Western Roman Empire.

Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine Period

In late antiquity, Baia’s occupation became intermittent, reflecting the broader instability of the period. The region came under Ostrogothic and subsequently Byzantine control during the Gothic Wars of the 6th century CE. While no direct evidence of military engagements at Baia exists, the nearby Bay of Naples held strategic importance. Thermal facilities at Baia show limited continued use, with some architectural repairs indicating attempts at maintenance or reuse. The site’s gradual abandonment is closely linked to bradyseismic ground subsidence and marine inundation characteristic of the Phlegraean Fields, which damaged structures and discouraged permanent settlement. No epigraphic or ecclesiastical records identify Baia as a bishopric or religious center during this era, suggesting a diminished civic and religious role.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Roman Republican Period

During the Roman Republican era, Baia was a small coastal community within Campania, recently incorporated into Roman territory. The population likely comprised local Campanian inhabitants alongside Roman settlers, organized into patriarchal family units typical of the period. Social stratification was limited, with small landowners and fishermen predominating. Men engaged in agriculture and fishing, while women managed domestic affairs. Economic activities centered on exploiting thermal springs and coastal resources, supporting subsistence agriculture including grain and olives. No evidence of large-scale industry or commerce has been identified for this period. Domestic architecture was modest, with simple wall plaster and minimal decoration. Clothing styles conformed to Roman Republican norms, adapted to the coastal climate. Trade and transport relied on maritime routes connecting Baia to Naples and other regional centers. Religious practices were primarily domestic and local, with no evidence of formal temples or organized civic cults. Baia functioned as a rural village without municipal status.

Roman Imperial Period (1st century BCE – 4th century CE)

In the Imperial period, Baia underwent a marked transformation into a prestigious resort favored by Rome’s elite. The population diversified to include senators, imperial freedmen, and their households, supported by slaves, artisans, and service personnel. Elite villas, such as the Villa dell’ambulatio, featured terraced layouts and luxurious amenities, reflecting a hierarchical social structure centered on landowning aristocrats. Women managed domestic spaces and participated in social rituals consistent with Roman elite customs. Economic life focused on leisure and hospitality, with extensive thermal complexes—misnamed temples—serving as sophisticated bathhouses utilizing geothermal vapors. Skilled labor in masonry, plumbing, and decoration supported a local artisan class. Dietary evidence and literary sources indicate consumption of fish, olives, bread, and imported delicacies, reflecting elite tastes. Interior decoration included marble friezes, frescoes (notably in the Temple of Sosandra), and mosaic floors, emphasizing aesthetic refinement. Baia’s coastal location facilitated importation of luxury goods via maritime routes, while local markets supplied everyday needs. Transportation combined sea travel with road connections to Naples and Rome. Religious life remained largely private and domestic, with no public temples; the so-called temples were secular thermal buildings. Baia held no formal municipal status but enjoyed imperial patronage as a leisure enclave.

Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine Period

By late antiquity, Baia experienced demographic decline and social reorganization due to volcanic activity and imperial instability. The population contracted, with many elite residents abandoning their villas, leaving a reduced community of caretakers, artisans, and rural inhabitants. Family structures simplified, and social stratification diminished. Economic activities contracted to essential services and limited agriculture. Archaeological evidence indicates partial reuse and repair of thermal facilities, suggesting continued but reduced bath use. Diet likely became simpler, relying on local produce and fish. Domestic decoration declined, with fewer frescoes and less elaborate furnishings. Transport and trade diminished as maritime routes were disrupted by environmental hazards and political turmoil. Christianization affected the region, but Baia lacks evidence of ecclesiastical institutions or bishoprics, possibly depending on nearby Naples for religious functions. The site lost administrative importance, becoming a marginal settlement within the province of Campania et Samnium.

Remains

Architectural Features

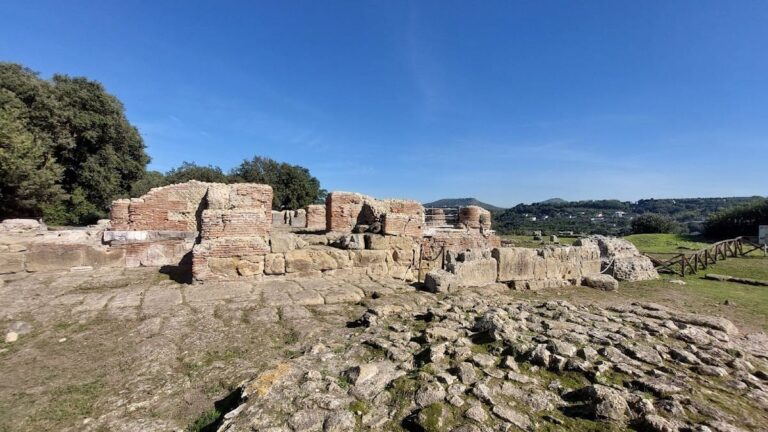

The archaeological remains at Baia predominantly comprise residential and recreational structures dating from the late Republican period through the 4th century CE. The site occupies a volcanic promontory with foundations built on tuff rock and Roman concrete (opus caementicium). Construction techniques include opus reticulatum (diamond-shaped stonework) and opus latericium (brickwork), with extensive use of vaulted chambers and hypocaust heating systems indicative of thermal bath complexes. The architectural layout adapts to the sloping terrain through terraces oriented toward the sea. The remains confirm Baia’s function as a leisure and residential settlement rather than a civic or military center. Over time, the built environment expanded during the 1st century BCE and CE, followed by contraction and partial abandonment in the 3rd and 4th centuries CE. Many structures survive as fragmentary walls, vaulted rooms, and mosaic floors, while others are submerged or buried beneath volcanic deposits. Conservation efforts have stabilized several ruins, though many remain in a fragmentary state.

Key Buildings and Structures

Villa of the Tritons

Dating to the 1st century CE, the Villa of the Tritons is a large seaside residential complex featuring multiple terraces and rooms arranged around courtyards. The masonry combines opus reticulatum with brickwork, and the villa includes vaulted cisterns for water storage. Noteworthy are mosaic floors depicting marine motifs, including tritons, which inspired the villa’s modern name. The complex incorporates thermal baths with caldarium (hot bath) and frigidarium (cold bath) rooms heated by hypocaust systems. Some rooms exhibit modifications from the 3rd century CE, possibly reflecting partial reuse or repair during the site’s decline.

Bath Complex near the Harbor

Constructed circa 50 BCE, this bath complex exploits the natural thermal springs of the Phlegraean Fields. The structure comprises a series of heated rooms with hypocaust flooring, vaulted ceilings, and large pools. The caldarium and tepidarium (warm bath) are identifiable by brick-lined walls and remnants of heating channels. The irregular layout adapts to the volcanic terrain. Excavations have uncovered fragments of marble cladding and decorative stucco. The baths remained in use until the 4th century CE, with evidence of partial abandonment and structural collapse in late antiquity.

Harbor Structures

Harbor installations primarily date to the 1st century BCE and CE and include stone quays and breakwaters constructed with large tuff blocks and Roman concrete. The harbor basin is partially submerged due to bradyseismic subsidence. Archaeological surveys have documented mooring posts and remains of warehouses adjacent to the quays. The harbor facilitated maritime access but lacks fortifications. Some structures show repair traces from the 3rd century CE, though overall use declined thereafter.

Villa of Sosandra

Dating to the late 1st century BCE, the Villa of Sosandra is a residential complex centered on a rectangular peristyle courtyard surrounded by rooms. Walls are built in opus reticulatum with brick accents. Excavations revealed mosaic floors with geometric patterns and fresco fragments depicting female figures and a satyr with a thyrsus. The villa includes a private bath suite with hypocaust heating. Structural modifications in the 2nd century CE indicate continued occupation, but partial abandonment occurred by the 4th century CE. The villa’s name derives from a statue of Sosandra found in 1953, now housed in the National Museum of Naples.

Temple of Diana

Situated on the promontory’s highest point, the so-called Temple of Diana dates to the 1st century BCE. The surviving remains include a podium constructed in opus incertum (irregular stonework) and fragments of columns and capitals. The cella (inner chamber) foundations and altar base are partially preserved. Archaeological evidence indicates the building functioned as a thermal chamber collecting geothermal vapors rather than a religious temple. The structure was decorated with marble friezes depicting hunting scenes. The dome, originally a large ogival vault, is now partially collapsed. The building is visible from the nearby Cumana train station.

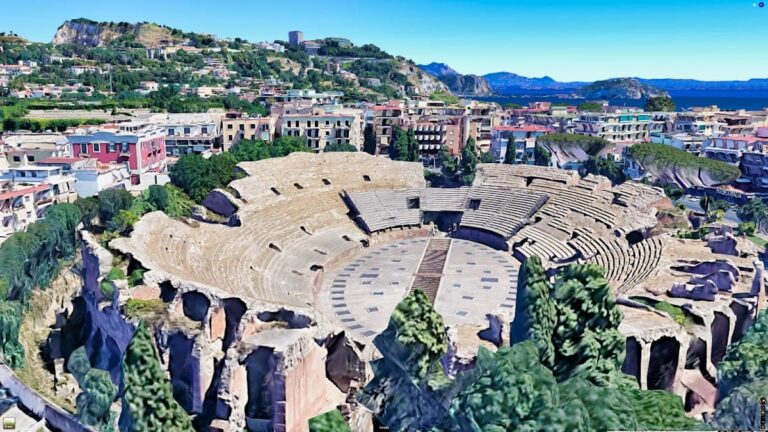

Temple of Mercury

Also known as the “truglio” due to its circular plan, the Temple of Mercury served as a frigidarium (cold bath). Descriptions from the 18th century report six niches within the interior, four semicircular in shape. The vaulted ceiling features a central oculus (lumen) and is constructed with large wedge-shaped tuff slabs. The building’s thermal function is confirmed by its architectural features, distinguishing it from religious temples.

Temple of Venus

This octagonal thermal building is sunken approximately three meters below ground level. It features eight lowered-arch windows with an internal gallery running along them, overlooking a central pool. The structure was named after a statue found by Scipione Mazzella and identified with the goddess Venus. Excavations led by Michele Arditi uncovered the building, which functioned as part of the thermal complex rather than a cult site.

Villa dell’ambulatio

The Villa dell’ambulatio is a scenic residential complex overlooking the sea, composed of a series of terraces connected by a complex system of staircases. The final stairway leads to the Mercury sector, integrating the villa with adjacent thermal facilities. The architectural arrangement emphasizes views and access to the coastline, reflecting elite leisure preferences.

Temple of Sosandra

Located between two parallel staircases, the Temple of Sosandra is named after a statue discovered in 1953, now housed in the National Museum of Naples. The building contains wall paintings depicting female figures and a satyr holding a thyrsus, indicating decorative programs consistent with elite residential contexts. The structure’s function remains associated with leisure and thermal use rather than formal religious worship.

Nymphaeum of Emperor Claudius

Completely submerged underwater due to bradyseismic subsidence, the nymphaeum formed part of the imperial leisure complex. Sculptural works recovered from the site have been transferred to the Archaeological Museum of the Campi Flegrei, located in the Aragonese Castle. The nymphaeum’s original layout and decorative program remain partially understood due to submersion.

Other Remains

Additional archaeological features include small necropolises with funerary monuments dating from the 1st century BCE to the 2nd century CE, identified by stone cippi and sarcophagi fragments. Cisterns and aqueduct channels constructed in opus caementicium with waterproof mortar are scattered across the site. Fragments of porticoes and garden terraces with brick-faced concrete walls are visible. Near the harbor, remains of workshops and storage rooms have been identified through work surfaces and amphora fragments. No public latrines have been conclusively documented.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations have yielded pottery ranging from late Republican to late Imperial periods, including locally produced Campanian red gloss tableware and imported African and Eastern Mediterranean amphorae, indicating active trade networks. Domestic artifacts such as oil lamps, cooking vessels, and glassware have been recovered from villas and bath complexes. Inscriptions are scarce but include dedicatory plaques and graffiti dating mainly to the 1st and 2nd centuries CE. Coins from the late Republic through the 4th century CE, featuring emperors such as Augustus, Nero, and Constantine, reflect the site’s occupation span. Tools related to agriculture and crafts, including metal implements and ceramic molds, have been found primarily near the harbor. Religious artifacts include small bronze statuettes and altar fragments associated with the Temple of Diana and domestic shrines, dating mainly to the 1st and 2nd centuries CE. No large-scale cultic or ecclesiastical installations from late antiquity have been identified.

Preservation and Current Status

The preservation of Baia’s ruins varies considerably. The Villa of the Tritons and the harbor bath complex retain substantial wall sections and mosaic floors, although many vaults have collapsed. The Temple of Diana survives primarily as foundation remains and scattered architectural fragments. Harbor structures are partially submerged and subject to marine erosion. Several villas exhibit fragmentary walls and collapsed roofs, with some mosaics exposed but weathered. Restoration efforts since the 18th century have included masonry consolidation and partial reconstruction using modern materials, particularly at the Villa of the Tritons. Conservation focuses on stabilizing ruins rather than full reconstruction. Vegetation growth and erosion remain ongoing threats, especially in less monitored areas. The site is managed by local heritage authorities, with some areas accessible as an open-air museum, while others remain closed for preservation. Excavations continue intermittently, accompanied by structural monitoring and preventive conservation.

Unexcavated Areas

Significant portions of Baia remain unexcavated, especially in the northern and western sectors of the promontory. Surface surveys and geophysical studies have identified subsurface anomalies consistent with buried building foundations and road networks. Historical maps from the Renaissance and early modern periods suggest additional villa complexes and harbor-related structures beyond currently excavated zones. Modern urban development and environmental protection regulations limit extensive excavation. Future investigations prioritize non-invasive methods to map subsurface remains, with some areas preserved in situ to prevent damage from excavation and exposure. No large-scale excavation campaigns are currently underway, but heritage authorities maintain targeted research and conservation programs.