Ramnous: An Ancient Fortified Deme and Sanctuary in Attica

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.5

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Country: Greece

Civilization: Greek, Roman

Remains: City

Context

The Archaeological Site of Ramnous is situated in northeastern Attica, near the contemporary village of Grammatiko. It occupies a coastal promontory overlooking the South Euboean Gulf, combining an elevated plateau with descending slopes that lead to a modest coastal plain. The site lies approximately forty kilometers northeast of central Athens by modern roadways, positioning it along ancient maritime routes.

Archaeological evidence attests to continuous occupation at Ramnous from the Archaic period through late antiquity. The site’s landscape includes an Archaic sanctuary established in the sixth century BCE, which expanded significantly during the fifth century BCE. Fortifications and civic structures dating to the Classical and Hellenistic periods reflect its military and administrative importance. Inscriptions and architectural modifications from the Roman Imperial era demonstrate ongoing use, while material culture indicates a decline in occupation during late antiquity.

European travelers first documented the ruins in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, prompting systematic archaeological investigations in the twentieth century. Excavations have uncovered inscriptions, votive offerings, and architectural fragments.

History

Ramnous held a significant position in northeastern Attica’s historical landscape from the Archaic period through late antiquity. Its commanding location overlooking the South Euboean Gulf rendered it a critical military outpost and religious center, particularly renowned for its sanctuary dedicated to Nemesis, the goddess embodying retribution. The site’s archaeological record, including fortifications, temples, and inscriptions, reveals a sustained sequence of occupation and adaptation that mirrors broader political and cultural developments in Attica and the wider Greek world.

Archaic and Classical Period (Late 6th century – 4th century BCE)

During the Archaic and Classical periods, Ramnous functioned as a deme of Attica affiliated with the tribe Aeantis. Its position on a rocky peninsula overlooking the Euboean Strait was strategically vital for monitoring maritime traffic. The Athenians maintained a permanent garrison of ephebes—young men undergoing military training—stationed on the acropolis to oversee naval movements. The site gained prominence for its sanctuary of Nemesis, which comprised two temples. The smaller, earlier temple, constructed of poros stone with a Doric portico, dated to the late sixth century BCE and was dedicated jointly to Nemesis and Themis. This structure was likely destroyed during the First Persian invasion (480–479 BCE), possibly by Persian forces prior to the Battle of Marathon.

In the early fifth century BCE, the smaller temple was reconstructed in Doric style, potentially serving as a treasury for the larger temple erected between approximately 460 and 420 BCE. The larger temple, contemporaneous with the Parthenon and attributed to the architect Kallikrates, was a Doric peripteral edifice. Its construction was interrupted by the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War in 431 BCE, leaving certain architectural elements, such as column fluting and stylobate finishing, incomplete. This temple housed a monumental marble cult statue of Nemesis, approximately four meters in height, sculpted by Agoracritus, a pupil of Phidias. The statue’s base featured a nearly three-dimensional relief depicting Helen being presented to Nemesis by Leda.

The sanctuary was enclosed by a substantial artificial platform supported by a white marble wall constructed in the Lesbian polygonal masonry style. Politically, Ramnous was active within the Athenian democratic system, sending eight representatives to the Boule during the early Classical period. The deme’s fortifications and civic buildings from this era underscore its dual function as a religious sanctuary and a military stronghold guarding Attica’s eastern coastline.

Late Classical and Hellenistic Period (4th – 3rd century BCE)

In the late Classical period, around 413 BCE, Ramnous underwent significant fortification with the construction of robust city walls enclosing the acropolis, situated on a hill approximately 28 to 30 meters in height. These walls, built from locally quarried marble near Agia Marina, reached about six meters in height and measured between 2.3 and 2.7 meters in thickness. Within the fortified precinct, public buildings such as a small theatre, a gymnasium, and a sanctuary dedicated to Dionysos were established, reflecting an expansion of civic and cultural activities beyond the earlier religious and military functions. Residential structures were present both inside and outside the fortifications, indicating a developed settlement pattern.

During the Hellenistic period, Ramnous experienced military turbulence. In 295 BCE, Demetrius I of Macedon briefly seized the site, which was soon restored to Athenian control. Subsequently, during the Chremonidean War (268/267–261 BCE), Ramnous served as a strategic base for Ptolemaic allied forces. The large temple of Nemesis sustained severe damage at its eastern end, likely inflicted during raids by Philip V of Macedon around 200 BCE. Roman-era restorations replaced damaged architectural components with marble blocks exhibiting different tooling techniques. The smaller temple remained in use until the fourth century CE. The cult statue of Nemesis was destroyed by early Christian iconoclasm, but numerous fragments have been recovered and reconstructed, enabling identification of eleven smaller Roman copies. Ramnous also maintained sanctuaries dedicated to Aphrodite Hegemone, Dionysos, Zeus Soter, Athena Soteira, and local heroes Archegetes and Aristomachos. Dionysian festivals featuring theatrical performances and torch races in honor of Nemesis were integral to the deme’s religious calendar. Funerary monuments, including the Pentelic marble stele of Hieron and Lysippe (circa 325–300 BCE), were situated along the road connecting Ramnous to Marathon.

Roman Period (1st – 4th century CE)

Under Roman administration, Ramnous continued as an inhabited and active settlement, as evidenced by inscriptions and literary references such as those by Pliny the Elder. Around 46 CE, dedications at the sanctuary honored the deified Livia, wife of Emperor Augustus, and Emperor Claudius, indicating the site’s integration into the imperial cult. In the second century CE, the affluent Greek aristocrat Herodes Atticus contributed busts of Emperors Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, as well as a statue of his pupil Polydeucion, to the sanctuary.

The large temple of Nemesis underwent extensive restorations during this period, particularly at its eastern end, reflecting Roman interest in preserving classical Greek monuments. Unlike many other Attic temples, it was neither stripped of materials nor dismantled for reuse in Athens. The cult of Nemesis formally ceased in 382 CE following Emperor Arcadius’s edict mandating the destruction of rural polytheistic temples. Despite this, the sanctuary and fortress ruins remained visible and were not entirely dismantled. The marble head of the Nemesis statue, discovered in the early nineteenth century, exhibits stylistic affinities with the Parthenon pediments and is now housed in the British Museum. The smaller temple continued to be preserved until the fourth century CE, marking the site’s gradual decline as pagan worship waned in late antiquity.

Late Antiquity

Archaeological data indicate a marked decline in occupation at Ramnous during late antiquity. The suppression of pagan cults and the ascendancy of Christianity led to the abandonment of the sanctuary of Nemesis. No inscriptions or architectural modifications attributable to the Byzantine period have been identified, though some structural remains suggest limited continued use or habitation. The fortifications and temples fell into ruin, yet their remains persisted in the landscape, preserving Ramnous’s historical presence into the medieval era.

This historical trajectory situates Ramnous within the evolving political and religious milieu of Attica and the broader Greek world. From its origins as a fortified deme and religious sanctuary to its adaptation under Hellenistic and Roman rule, Ramnous exemplifies the complex interplay of military strategy, civic identity, and religious devotion across centuries.

Remains

Architectural Features

The core of Ramnous is a fortified acropolis situated on a hill approximately 28 to 30 meters high, encompassing an area of about 230 by 270 meters. The acropolis is enclosed by substantial city walls constructed primarily of local marble quarried near Agia Marina. These fortifications, dating mainly to circa 413 BCE, reach approximately six meters in height and have a thickness ranging from 2.3 to 2.7 meters. The principal city gate, located on a narrow ridge adjoining the southern wall, remains well-preserved and stands about 6.1 meters tall.

The fortifications extend beyond the acropolis to include a small theatre, a gymnasium, and a sanctuary dedicated to Dionysos, alongside several public buildings and residential dwellings. The layout reflects a combined military and civic function, with the acropolis serving as a garrison for Athenian ephebes responsible for overseeing maritime navigation. In later periods, the fortress was known by various names, including Taurokastron and Ovriokastron. The site’s fortifications were maintained through multiple conflicts, including Macedonian occupation in 295 BCE and use by Ptolemaic allies during the Chremonidean War (268/267–261 BCE).

Key Buildings and Structures

Sanctuary of Nemesis

Located approximately 600 meters south of the town along the road to the principal gate, the sanctuary of Nemesis occupies a large artificial platform supported by a pure white marble wall constructed in the Lesbian polygonal masonry style. This wall forms the temenos, or sacred enclosure, within which stand two principal temples: a smaller temple dedicated jointly to Nemesis and Themis, and a larger temple devoted exclusively to Nemesis.

Small Temple of Nemesis and Themis

The small temple dates originally to the late sixth century BCE but was destroyed during the First Persian invasion (480–479 BCE) and subsequently rebuilt in the early fifth century BCE in Doric style. Constructed of poros stone, its walls and terrace employ Lesbian polygonal masonry. The temple’s plan comprises a cella and a portico with two Doric columns in antis, measuring approximately 6.15 by 9.9 meters and following a 6 × 12 Doric column arrangement. Dedicatory inscriptions on marble seats from the fourth century BCE confirm its dual dedication to Themis and Nemesis. Later, the temple likely functioned as a treasury for the larger temple, housing cult statues. Several cuttings on the temple steps indicate the placement of stelai (inscribed stone slabs). Among the ruins, an archaic-style statue fragment attributed to the Aeginetan school was found and is now housed in the British Museum. Statues of Themis and other dedications from the cella are preserved in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Large Temple of Nemesis

Construction of the larger temple commenced circa 460–450 BCE and continued until approximately 430–420 BCE, with work interrupted by the Peloponnesian War beginning in 431 BCE. This Doric peripteral hexastyle temple measures about 22 meters in length and 10 meters in width, featuring 12 columns on each side. Its layout includes a pronaos (front porch), cella (main chamber), and posticum (rear porch) in the typical Greek temple arrangement. The stereobate and lower crepidoma (stepped platform) were built from local black marble, while the upper parts utilized white marble. Notably, the column flutes were never carved, and stylobate blocks were left unfinished with protective excess marble on corners and upper surfaces, indicating incomplete construction.

No sculpted pediments or decorated metopes survive, but the roof was adorned with sculpted akroteria (ornamental statues). The eastern end of the temple suffered severe damage, likely from raids by Philip V of Macedon around 200 BCE. Roman-period repairs replaced damaged architectural elements, including the architrave, frieze, cornices, gables, akroteria, roof gutters, tiles, and ceiling coffers. An inscription on the central architrave block at the east end records a rededication to the deified Livia, wife of Augustus, by the local Demos, possibly linked to these repairs. Unlike many other Attic temples, this temple was restored rather than dismantled or stripped for materials in antiquity.

Cult Statue of Nemesis

The cella of the large temple housed a colossal cult statue of Nemesis, approximately four meters tall, sculpted from Parian marble by Agorakritos, a pupil of Phidias. According to Pausanias, the marble block was originally brought by the Persians as a trophy but was repurposed by Phidias or Agorakritos as an act of retribution. The statue’s base, about 90 centimeters high and 240 centimeters wide, features a nearly in-the-round relief depicting Helen being presented to Nemesis by Leda on three sides. Fragments of a colossal statue matching this size were found on site, made of Attic marble rather than Parian, raising questions about the traditional account.

Numerous fragments of the original statue have been recovered and reconstructed, enabling identification of eleven smaller Roman copies. A large over life-size marble head from the cult statue, with perforations for a gold crown, was discovered in the early nineteenth century by John Gandy and is now in the British Museum. This head stylistically resembles the Parthenon pediment sculptures dated 440–432 BCE. The Roman historian Varro praised the statue as an exemplary work of Greek sculpture.

Theatre

A small theatre is located within the fortified area on the hillside below the acropolis. Enclosed by the city walls, it is associated with Dionysian cult activities. The theatre’s seating area and stage remain partially preserved, indicating its use for performances such as comedies and other theatrical events.

Gymnasium

The gymnasium lies within the fortified enclosure near the theatre and other public buildings. Its remains include structural foundations consistent with spaces used for physical training and social activities typical of Greek gymnasia.

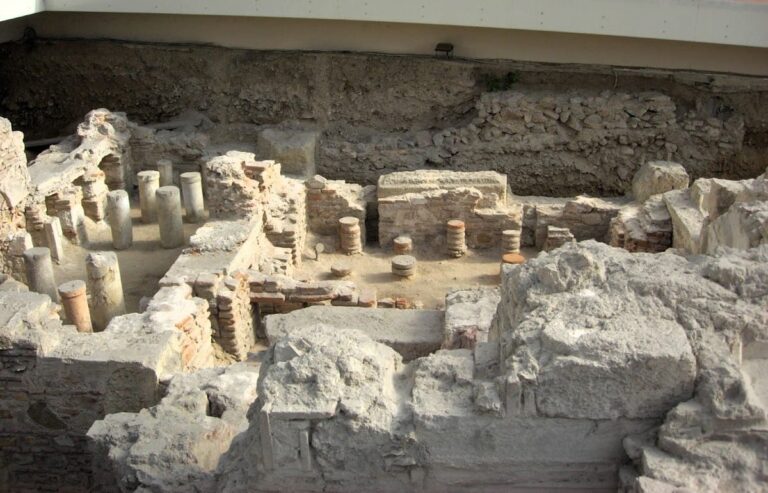

Sanctuary of Dionysos

A small sanctuary dedicated to Dionysos is situated within the fortified area of the city. The remains include architectural fragments and foundation walls that mark the sacred precinct.

Other Religious Structures

Additional sanctuaries and temples have been identified in the vicinity, including a temple dedicated to Amphiaraos (Amphiareion). Other cult sites within or near the settlement were devoted to Aphrodite Hegemone, Zeus Soter, Athena Soteira, and local heroes Archegetes and Aristomachos. These survive as foundation traces and scattered architectural fragments.

Burial Monuments

Numerous funerary monuments and grave enclosures have been found along the road connecting Ramnous to Marathon. A notable example is a Pentelic marble funerary relief dating to circa 325–300 BCE, depicting a mature bearded man leaning on a staff and a young woman silently clasping hands, symbolizing posthumous union. This relief is associated with the tomb enclosure of Hierocles and is housed in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens. The funerary monument includes an inscribed pediment naming Hieron, son of Hierocles, and Lysippe.

Other Remains

Outside the city walls, numerous buildings, including residential dwellings, have been documented through surface traces and excavation. The fortified area also contained various public buildings, though specific identifications beyond those mentioned are limited. Architectural fragments and scattered remains indicate additional structures, but details remain sparse.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations at Ramnous have yielded numerous inscriptions, including dedicatory texts to Themis and Nemesis, as well as a rededication inscription to Livia, wife of Emperor Augustus. These inscriptions provide direct evidence of religious dedications and political affiliations spanning from the Classical through the Roman Imperial periods.

Religious artifacts recovered include statues of Themis and Nemesis, with fragments of the colossal Nemesis statue reconstructed from marble pieces. Eleven smaller Roman copies of the Nemesis statue have also been identified. Funerary reliefs, such as the Pentelic marble stele of Hieron and Lysippe, contribute to understanding burial practices.

Pottery and votive material from the Archaic through Roman periods have been found within the sanctuary and settlement areas, though specific details on types and origins are limited in the sources. Architectural fragments, including marble blocks, column drums, and decorative elements, have been documented extensively, reflecting construction phases and repairs.

Preservation and Current Status

The city walls and principal gate of the fortified acropolis are well-preserved, with the gate standing about six meters high. The sanctuary’s marble enclosure wall remains visible, supporting the artificial platform of the Nemesis sanctuary. The small and large temples of Nemesis survive in partial ruin, with the large temple showing evidence of Roman repairs, especially at its eastern end. The column flutes and some architectural details remain unfinished, reflecting interrupted construction.

The theatre, gymnasium, and sanctuary of Dionysos retain foundation remains and partial structural elements. Burial monuments along the Marathon road survive as reliefs and inscribed stones, some housed in museums. The marble head of the Nemesis statue, discovered in the early nineteenth century, is preserved in the British Museum.

Systematic excavation and conservation have been ongoing since the late nineteenth century, with major work continuing under the direction of Vasileios Petrakos since 1975. The site is preserved largely in situ under Greek archaeological supervision, with no evidence of modern reconstruction using non-original materials reported.