Aptera: An Archaeological Site of Strategic and Cultural Importance in Crete, Greece

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.6

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.ancientaptera.gr

Country: Greece

Civilization: Byzantine, Greek, Roman

Remains: City

Context

The Archaeological Site of Aptera is situated on a limestone promontory above the modern village of Megala Chorafia, near the city of Chania on the northwest coast of Crete, Greece. The site occupies a naturally defensible hilltop and adjacent terraces that command extensive views over Souda Bay and the fertile Kalydon plain. This strategic location provided control over maritime routes and inland access, factors that contributed to its historical significance.

Archaeological evidence demonstrates continuous occupation from the Late Bronze Age through the Byzantine period. Early activity is attested by burial deposits and surface pottery, while later phases reveal urban development and complex civic structures. The site’s landscape includes natural springs and water catchment features, which were supplemented by large cisterns to support the settlement’s water needs. Aptera’s remains encompass fortifications, public buildings, religious sanctuaries, residential quarters, and necropoleis, reflecting its evolving role in regional political, military, and religious networks over more than a millennium.

Systematic archaeological investigations began in the late nineteenth century and have continued under the auspices of the Greek Archaeological Service and academic institutions. Many artifacts recovered from Aptera are curated in the Chania Archaeological Museum. Conservation efforts have facilitated ongoing research and controlled public access, preserving the site’s integrity within its natural setting.

History

Aptera’s long history of occupation spans from the Late Bronze Age through the Byzantine era, reflecting its enduring strategic and civic importance in northwest Crete. Its commanding position overlooking Souda Bay enabled it to function as a fortified settlement, a city-state, and later a Roman municipium. The site’s archaeological record documents phases of urban growth, military engagement, religious transformation, and eventual decline, mirroring broader historical developments in Crete and the Eastern Mediterranean.

Late Bronze Age (14th–13th centuries BC)

During the Late Bronze Age, Aptera is identified in Mycenaean Linear B tablets as “A-pa-ta-wa,” confirming its recognition within the palatial administrative system. The associated Minoan settlement was located approximately 1.5 kilometers from the later city site, near present-day Stylos, indicating a relocation of habitation from the Bronze Age to the Classical and later hilltop site. Archaeological evidence from this period primarily consists of burial deposits and surface pottery, with limited architectural remains at the later city location, suggesting a modest settlement or ritual use rather than a fully developed urban center.

Archaic and Classical Periods (8th–4th centuries BC)

In the Archaic and Classical periods, Aptera emerged as a fortified city-state within the Cretan political landscape. Initially subordinate to the nearby city of Kydonia, Aptera developed its own civic identity and military infrastructure. Before the mid-4th century BC, the city constructed extensive fortifications encompassing a 3,480-meter-long wall on the Paliokastro hill, a natural stronghold 231 meters above sea level. The defensive system included six towers, multiple gates, and sally ports, designed to resist siege engines and provide strategic control over approaches.

The fortification walls exhibit diverse masonry techniques adapted to the terrain, including polygonal and pseudo-isodomic ashlar masonry. The principal western gate was flanked by a rectangular tower equipped with arrow slits and openings for war machines, reflecting advanced military architecture. Archaeological finds near the west wall, such as catapult bolts, sling bullets, spearheads, and arrowheads, attest to a siege during the Cretan War of 220 BC. Aptera was actively involved in regional conflicts, including wars against Kydonia and shifting alliances during the Lyttian War, initially siding with Knossos before aligning with the Polyrrhenians against it.

Religious life in this period is evidenced by a small two-room temple dating to the 5th century BC, constructed of dressed ashlar blocks connected with iron clamps and dowels. This temple, likely dedicated to Artemis and Apollo—the city’s tutelary deities—was built atop an earlier sacred site used since the Geometric period. The surrounding sanctuary area remained in use through Byzantine times. The city’s port was Cisamus, as recorded by Strabo, linking Aptera to maritime trade and communication networks. Urban planning included paved roads facilitating access to public buildings such as the theatre and sanctuaries, indicating organized civic development.

Hellenistic Period (3rd century BC)

The Hellenistic era marked a period of urban expansion and architectural sophistication at Aptera. The city constructed a large theatre in the early 3rd century BC, situated near the southeast gate within a natural hollow facing south. Built of local fossiliferous limestone, the theatre’s semicircular seating area measured approximately 54.68 meters in diameter, divided into four wedge-shaped sections by five staircases, with at least 26 rows of seats preserved. The orchestra was notably small, with a radius of 5.45 meters. Shortly after, a rectilinear theatre was erected against the rear of the main theatre, facing north. This smaller structure, seating between 600 and 720 spectators, likely served cultic, athletic, or political functions, reflecting Minoan theatrical traditions associated with chthonic deities.

During this period, Aptera’s fortifications and urban layout demonstrate advanced military and civic planning. Inscriptions and coinage from the Hellenistic era confirm the city’s status as a recognized polis with established institutions. The city maintained its strategic and cultural significance amid the shifting political landscape of Crete, balancing military preparedness with religious and social activities.

Roman Period (1st century BC – 4th century AD)

Under Roman administration, Aptera was incorporated into the province of Crete and Cyrenaica and later the Diocese of Asia. The city experienced substantial urban development, including two major remodeling phases of the theatre during the 1st century AD. Public amenities expanded with the construction of two large bath complexes, supplied by extensive vaulted cisterns built of Roman concrete (opus caementicium) with waterproof hydraulic mortar and reinforced with buttresses. Inscriptions identify Varius Lucius Lampadis, an Athenian benefactor, as a patron of one bath complex, indicating cultural and economic connections beyond Crete.

A large Roman urban house dating to the 1st century AD was built west of the theatre, featuring a Greek-style peristyle courtyard with Ionic and Doric columns, sophisticated water management including a large cistern replacing the typical impluvium, and domestic installations such as an olive press and stone mortar. This residence was occupied until its destruction by the earthquake of 365 AD. Funerary monuments near the western gate commemorate affluent families and notable citizens, with inscriptions linking Aptera to other Cretan cities like Eleutherna. The city’s fortifications remained functional, with the main gate road showing cart ruts and defensive towers equipped for war machines. The scale and complexity of public and private buildings reflect Aptera’s prosperity and integration within the Roman provincial system.

Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine Period (4th–7th centuries AD)

During Late Antiquity, Aptera underwent administrative and religious transformations under the Eastern Roman Empire. The city suffered extensive damage from the earthquake of 365 AD, which affected many coastal settlements in the Eastern Mediterranean. Repairs to public buildings, including the baths, were limited, signaling a decline in urban vitality. A subsequent strong earthquake in the 7th century AD caused further destruction, including damage to funerary monuments and infrastructure.

Early Byzantine occupation is evidenced by the reuse of earlier funerary monuments for cist graves and the conversion of the two-room temple into a burial site. By the 12th century, a monastery dedicated to St. John Theologos was established on the site, comprising a chapel and a two-story block of monks’ cells within a fortified enclosure. This monastic complex remained active until 1964, marking the site’s continued religious significance despite the loss of its urban character. The decline of Aptera as a major urban center reflects broader regional shifts in political control, economic patterns, and population distribution during the early medieval period.

Medieval Period and Abandonment

The precise chronology and causes of Aptera’s final abandonment remain subjects of scholarly debate. Byzantine churches and defensive repairs attest to continued habitation into the medieval centuries, but the site gradually lost its urban functions. The monastery of St. John Theologos represents the last significant phase of occupation, serving as a religious community amid a declining settlement. No substantial evidence indicates major military or administrative activity after the Byzantine period. The site’s decline likely resulted from a combination of natural disasters, shifting political landscapes, and economic realignments affecting Crete during the Middle Ages, culminating in its eventual desertion.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Archaic and Classical Periods (8th–4th centuries BC)

During the Archaic and Classical periods, Aptera functioned as a fortified city-state with a structured social hierarchy. The population consisted primarily of Greek-speaking Cretans, including an elite class responsible for civic administration and religious leadership, as indicated by inscriptions referencing magistrates and local officials. Economic activities centered on agriculture, particularly olive cultivation and cereal farming, supported by maritime trade through the port of Cisamus. Artisanal production likely met local demands, while religious life revolved around sanctuaries dedicated to Artemis and Apollo, fostering communal rituals and festivals.

Domestic architecture comprised stone-built houses with modest decoration, while public spaces featured temples and paved roads facilitating access to cultural venues such as the theatre. Transportation relied on footpaths and carts along fortified routes, reflecting the city’s military preparedness amid regional conflicts, including documented sieges during the Cretan War. Aptera’s civic institutions balanced religious, military, and economic functions, leveraging its strategic hilltop location to maintain regional influence.

Hellenistic Period (3rd century BC)

In the Hellenistic era, Aptera expanded its urban infrastructure and cultural life. The population remained predominantly Greek, with an active elite engaged in governance, as evidenced by inscriptions affirming the city’s polis status. Economic activities diversified, maintaining agricultural production while supporting enhanced public amenities such as the large theatre and the rectilinear cultic theatre. These venues hosted religious ceremonies, athletic contests, and political gatherings, indicating organized communal life.

Urban planning improved with paved roads and sophisticated fortifications adapted to military needs. Trade likely intensified via the port of Cisamus, facilitating the exchange of goods and ideas. Although specific evidence of domestic decoration is limited, the scale of public works suggests a community capable of supporting artisans and craftsmen. Aptera’s role as a fortified polis with advanced civic institutions underscored its regional importance amid shifting alliances and conflicts in Crete.

Roman Period (1st century BC – 4th centuries AD)

Under Roman rule, Aptera experienced significant urban growth and social stratification. The population included Roman settlers alongside native Cretans, with inscriptions naming benefactors such as Varius Lucius Lampadis and officials linked to other Cretan cities, reflecting integration within the provincial administrative network. Economic life flourished with large-scale olive oil production, as evidenced by olive press remains in urban houses, and active participation in regional trade through the port of Cisamus.

Public amenities included two extensive bath complexes featuring hypocaust heating systems and large cisterns, demonstrating advanced water management and elevated living standards. Domestic architecture featured spacious urban houses with peristyle courtyards, decorated with sculptures and wall paintings that reflect Greco-Roman cultural influences. Markets likely offered a variety of goods, including imported luxury items, while transportation combined paved roads with maritime routes. Funerary monuments and hero cults reveal a socially stratified community honoring elite families and civic leaders. Religious life continued with traditional Greco-Roman deities, and civic administration operated through local magistrates and councils. Aptera functioned as a municipium within the Roman provincial framework, maintaining military defenses and public infrastructure that underscored its regional prosperity.

Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine Period (4th–7th centuries AD)

Following the earthquake of 365 AD, Aptera’s urban vitality declined, with population contraction and reduced economic activity. The community adapted by modestly repairing public buildings and repurposing earlier structures, such as converting the two-room temple into a burial site and reusing funerary monuments for cist graves. Economic life shifted toward subsistence, with diminished large-scale production. The baths saw limited reuse, indicating a decline in public leisure activities. Domestic life likely became simpler, with fewer resources for elaborate decoration or construction.

Religious practices transitioned to Christianity, evidenced by the establishment of the monastery of St. John Theologos by the 12th century. Ecclesiastical leadership replaced earlier civic institutions, and the site’s fortified enclosure reflects ongoing security concerns amid regional instability. Aptera’s role transformed from a prosperous urban center to a religious site with reduced administrative significance, mirroring broader changes in Crete during Late Antiquity and the Early Byzantine era.

Medieval Period and Abandonment

During the medieval centuries, Aptera’s population further declined, and its urban character faded. The monastery of St. John Theologos remained the focal point of occupation, serving as a religious community until the mid-20th century. Defensive repairs suggest intermittent military concerns, but no evidence indicates significant administrative or commercial activity. Economic functions were minimal, likely limited to subsistence agriculture and monastic self-sufficiency. Transport was probably restricted to local footpaths, with maritime trade centered elsewhere. Religious life dominated, with the monastery providing spiritual and social cohesion. The site’s abandonment likely resulted from cumulative effects of natural disasters, shifting political control, and economic realignments in Crete during the Middle Ages. Aptera ceased to function as a civic center, its importance reduced to a monastic religious enclave before final desertion.

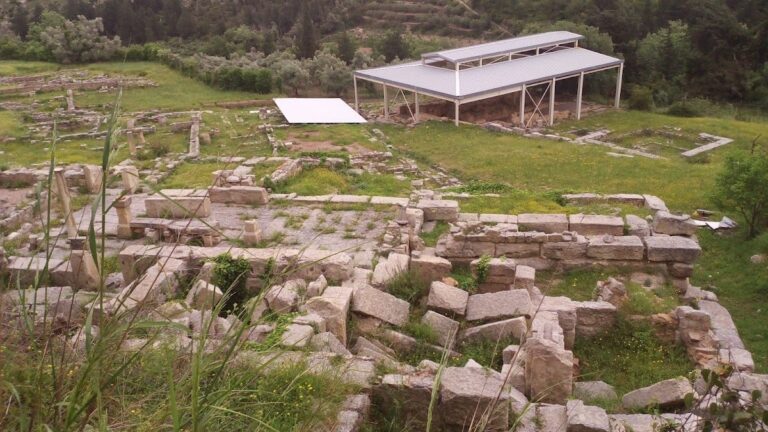

Remains

Architectural Features

Aptera’s archaeological remains are concentrated on a limestone hill and surrounding terraces overlooking Souda Bay. The city’s core is enclosed by a substantial fortification wall approximately 3,480 meters in length, constructed before the mid-4th century BCE. The wall’s masonry varies according to terrain, including large irregular stones on the north and northeast, polygonal and rectangular ashlar blocks on the east, and pseudo-isodomic ashlar masonry on the west and southwest. Six towers reinforce vulnerable sections, and multiple gates provide controlled access, notably the main western gate and the northeast “Iron Gate” (Sideroporti). The fortifications incorporate sally ports and multi-storey towers designed to accommodate defensive war machines.

Within the city, remains include public, religious, domestic, and funerary structures spanning Classical through Byzantine periods. The urban layout reflects successive construction and remodeling phases, particularly during the Hellenistic and Roman eras. Large water management installations, such as vaulted cisterns and bath complexes, attest to sophisticated hydraulic engineering. Religious architecture includes a small two-room temple dating to the 5th century BCE, built atop an earlier sacred site. Residential remains feature a large Roman urban house with a peristyle courtyard. Funerary monuments and a heroon near the main gate provide evidence of elite commemoration practices.

Key Buildings and Structures

Theatre

The main theatre, constructed in the early 3rd century BCE during the Hellenistic period, is located near the southeast gate in a natural hollow facing south toward the White Mountains. Built of local fossiliferous limestone, the semicircular seating area (cavea) measures approximately 54.68 meters in diameter and is divided into four wedge-shaped sections by five staircases. At least 26 rows of seats are preserved, extending beyond the currently visible area. The orchestra, a circular performance space, has a radius of 5.45 meters, one of the smallest known in ancient theatres.

The theatre underwent two Roman remodeling phases in the 1st century CE. The first phase lowered the orchestra floor and finalized the cavea’s form, while the second involved functional modifications and minor repairs. The structure suffered heavy damage in the 20th century due to a modern lime kiln and quarrying for quicklime, leaving mostly rubble masonry visible today. A well-preserved 55-meter-long Hellenistic paved road leads east of the theatre, providing access via the parodos (side entrance) and a wide staircase. This road also served nearby public buildings and sanctuaries.

Rectilinear Theatre

Constructed shortly after the main theatre in the first half of the 3rd century BCE, the rectilinear theatre is built against the rear of the horseshoe-shaped theatre, facing north. It measures approximately 50 meters in length, with four rows of seats preserved and foundations for two additional rows. Originally, it had 11 to 13 rows, seating an estimated 600 to 720 spectators. The seating area is divided into four roughly equal sections by four staircases, with central seats marked by carved cuts indicating reserved seating for important individuals.

This theatre resembles Minoan theatral areas used for religious ceremonies and athletic events and is classified as a “cultic theatre” associated with chthonic deities. Its function likely included religious ceremonies, athletic contests, or political gatherings depending on the city’s needs.

Bath Complexes

Two Roman bath complexes are partially excavated north of the three-aisled cistern. Bath I (east bath), dating to the 1st century CE, consists of two parts. The east side includes three hypocaust-heated rooms labeled A, B, and E. The west side contains two rooms with bathtubs (H and I), an arched room (IΔ), a corridor (K), and three partially excavated northern rooms (IA, IB, IΓ). Bath I also includes auxiliary corridors and furnace rooms (praefurnia) for heating. Room A measures 4.5 by 5 meters internally and is fully excavated, showing hypocaust pillars. A nearly square unheated room with a pebble floor, possibly an antechamber, is also present. An inscribed lintel names Varius Lucius Lampadis the Athenian as a probable benefactor, dated to the first half of the 1st or early 2nd century CE.

Bath II (west bath) contains eight vaulted rooms, including a hypocaust room, an arched room with two bathtubs, a furnace, and chimney ducts. Excavation of Bath II remains incomplete. It was supplied with water from the adjacent L-shaped cistern, indicating coordinated design. Both baths were heavily damaged by the earthquake of 365 CE, with some rooms roughly modified and reused afterward. Bath II’s walls are better preserved, while Bath I’s clearer ground plan allows hypotheses on interior layout. Comparable baths of similar date exist at other Cretan sites.

Cisterns

Two large vaulted cisterns from the Hellenistic period are carved into the rock to address the lack of natural springs on the city plateau. The three-aisled rectangular cistern measures 17 by 25 meters with a capacity of approximately 2,900 cubic meters. The L-shaped cistern has a long arm of 55.8 meters, a short arm of 34.2 meters, a width of 9 meters, and a capacity of about 3,050 cubic meters. Both cisterns have reinforced upper parts with exterior buttresses to counteract water pressure and were originally roofed with brick vaults, now collapsed.

Constructed of Roman concrete (opus caementicium) with waterproof hydraulic mortar coatings, the cisterns were free-standing public works likely collecting rainwater. Smaller surface conduits connected them to domestic cisterns. A small rectangular Hellenistic cistern lies between the L-shaped cistern and the bath to the north. The cisterns and baths were designed to supply large water quantities for daily use. Similar cisterns are known from other Mediterranean sites.

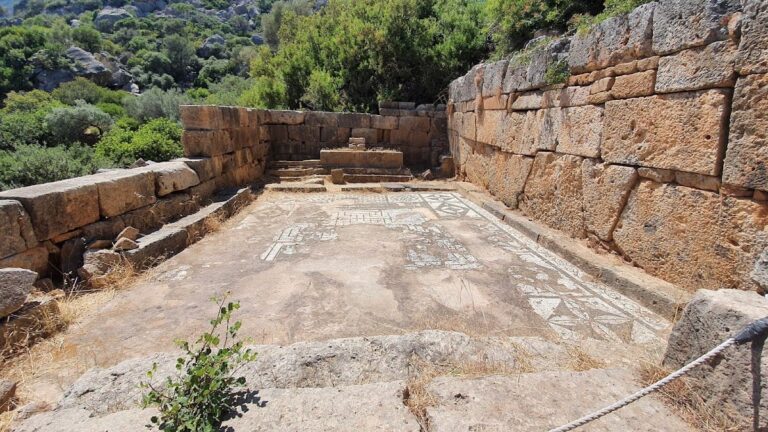

Two-Room Temple

A small two-room temple dating to the 5th century BCE is preserved to a low height. The building measures 6.32 meters long and 3.96 meters deep externally, with each interior room approximately 2.26 meters wide and 3 meters deep. Constructed of dressed ashlar blocks of uniform size, the stones are connected lengthwise with iron double-axe-shaped clamps and vertically with iron dowels. Entrances are located on the east side, and a small plain altar is enclosed in a corner.

Excavated in 1942, the temple yielded limited pottery and superstructure fragments. It was repurposed as a burial site during Byzantine times. The temple stands on an earlier sacred site used since at least the Geometric period. A paved road runs south of the temple toward the theatre, between it and a long retaining wall. The bipartite layout suggests joint worship of Artemis and Apollo during the Classical period. The temple was part of a larger cult sanctuary.

Public Building (Proposed Bouleuterion)

At the eastern edge of the fenced archaeological area, the west wall of a building with three niches is preserved to a considerable height. This structure is proposed to be the Bouleuterion (council house) of Roman Aptera, although no inscriptions confirm this identification. Test trenches inside revealed the building was founded on an earlier structure, indicating phases of construction or remodeling.

Roman House

A large Roman urban house west of the ancient theatre was built in the 1st century CE, likely after the earthquake of 66 CE. The excavated area covers approximately 765 square meters and is organized around a Greek-style peristyle courtyard with five by seven columns featuring Ionic bases and Doric capitals. The house was occupied with modifications until its destruction by the earthquake of 365 CE and partially reused in the 5th to 7th centuries CE.

Entrance is through a vestibule opening onto a paved public street running east-west south of the house, probably continuing from the theatre’s west parodos. The atrium lacks a typical impluvium (rainwater basin) but contains a large cistern to the south with an opening incorporated into the west wall, adjacent to a stone fountain base. An intact clay water jar dated to the late 3rd or early 4th century CE was found at the bottom of the cistern. Nearby are a stone olive press bed and a stone mortar, indicating domestic activities.

The peristyle courtyard likely contained gardens and was decorated with colorful wall paintings. Small decorative sculptures and a marble table base were found. West of the atrium are bedrooms (cubicula), and a room west of the cistern opening onto the peristyle may have served as a dining or reception room. Column drums and capitals lie fallen inside the courtyard, evidence of earthquake damage. The house follows a Hellenistic architectural type with a Greek peristyle courtyard added.

Fortifications and Main Gate

The city’s fortification wall encloses the Paliokastro hill plateau at 231 meters above sea level. Built before the mid-4th century BCE, the wall adapts to the terrain with varying construction techniques and widths. Six towers protect weak points, and the western side, more accessible, has three gates: two on the southwest and one on the northwest. The main gate on the western side features a smooth, sloping accessway, flanked by a rectangular tower on the west and a curtain wall on the east. Only the lower stones of the door jambs survive.

A 3.5-meter-wide paved road with broad, irregular slabs leads north to the gate, with visible cart ruts near the entrance. The tower was founded on bedrock, originally tall with two floors and a gable roof, equipped with arrow slits and openings for war machines. During the Roman Imperial period, funerary monuments of wealthy families were cut into the bedrock near the gate, including a marble inscription and painted plaster fragments, though these are poorly preserved.

The northeast gate, known as the “Iron Gate” (Sideroporti), retains well-preserved monolithic door jambs. A paved road from this gate led to the harbor at Kissamos and other cities. Sally ports are located at intervals along the west wall. Excavations on the west side revealed extensive siege traces from the Cretan War of 220 BCE, including catapult shots, sling bullets, spearheads, and arrowheads.

Heroon

Near the main gate, between the paved road and the western fortification wall, lies a heroon (hero shrine) containing inscribed sandstone statue bases dating to the 1st and 2nd centuries CE. The heroon is situated among two groups of cist graves. The first group includes 11 graves looted in late antiquity, dated from the Classical period to the 3rd century CE. The second group dates to the 6th or 7th century CE, identified by a typical lamp.

Five statue bases are partially or fully preserved; four bear inscriptions, and one likely did as well. One base preserves a full inscription, while others bear the word “hero” or a single letter. The inscriptions honor prominent citizens posthumously titled heroes. Traces of ritual pyres with offerings from the Hellenistic and Roman periods were found between the bases, including large cups and receptacles containing liquid remains and burnt fruit.

Funerary Monuments

Two funerary monuments are located outside the west fortifications near the main city cemetery. Funerary Monument I, founded in the 1st century CE, served as a mausoleum for a wealthy family. It contained ten burial shafts but was looted before its destruction in the 7th century CE. A funerary relief dated to the early 2nd century CE was found near the entrance, depicting a young couple likely buried there. This relief is among the best examples of its kind from Crete.

Funerary Monument II also served as a mausoleum for a wealthy family. Only the underground part survives, as the aboveground superstructure collapsed during the earthquake of 365 CE. The aboveground form is partly reconstructed from reused architectural fragments, including an Ionic epistyle with an integral frieze, cornice fragments, and fluted columns. The façade likely resembled a temple with a north-facing front of four Ionic or Corinthian columns or two columns in antis.

The epistyle bears a two-line inscription dated to the first half of the 2nd century BCE, naming Soterios son of Protogenes of Eleutherna as the maker, indicating alliances between cities. The underground part consists of an antechamber and burial chamber with four stone burial shafts, though graves were disturbed. Numerous objects were found in the antechamber, including metal implements, glass unguentaria, clay vases, terracotta figurines, and gold sheet fragments, dating the monument’s use to the early or mid-2nd century CE. Figurines indicate a connection to the mystery cult of Cybele. After destruction, Early Byzantine cist graves were built here using material from the monument.

Other Remains

The site includes a two-story block of monks’ cells and a chapel within a square monastery enclosure built by the 12th century, used until 1964. Several partially preserved Doric temples are present on the site. A Roman peristyle villa has been discovered, along with surface traces such as low walls and floor layers associated with various buildings. The Minoan settlement related to Aptera’s Bronze Age occupation lies about 1.5 kilometers away at modern Stylos and is not part of the main site.

Preservation and Current Status

The theatre’s seating remains partially preserved but was heavily damaged in the 20th century by lime kiln construction and quarrying for quicklime. The fortification walls and towers survive in varying states, with some sections well preserved and others fragmentary. The main gate retains its lower door jamb stones and the tower’s foundations. The baths are partially excavated, with Bath II’s walls better preserved than Bath I’s. The cisterns retain vaulted structures, though their original brick vaults have collapsed.

The two-room temple survives to a low height, with dressed ashlar masonry visible. The Roman house shows fallen columns and capitals inside the courtyard, evidence of earthquake damage. Funerary monuments are fragmentary, with underground chambers preserved but aboveground superstructures largely destroyed. The monastery complex remains as a two-story block of monks’ cells and a chapel within a fortified enclosure. Conservation and controlled excavation have stabilized many structures, with ongoing research conducted by the Greek Archaeological Service and university teams.

Unexcavated Areas

Some areas of the site remain partially excavated or poorly studied, including parts of the bath complexes and the proposed Bouleuterion, where excavation is incomplete. Surface surveys and early exploratory work have identified additional low walls and floor layers associated with various buildings, but these have not been fully excavated. No detailed information is available on future excavation plans or restrictions due to conservation policies.