Antigona Archaeological Park: An Ancient Hellenistic and Roman Site in Albania

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.4

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Country: Albania

Civilization: Byzantine, Greek, Roman

Remains: City

Context

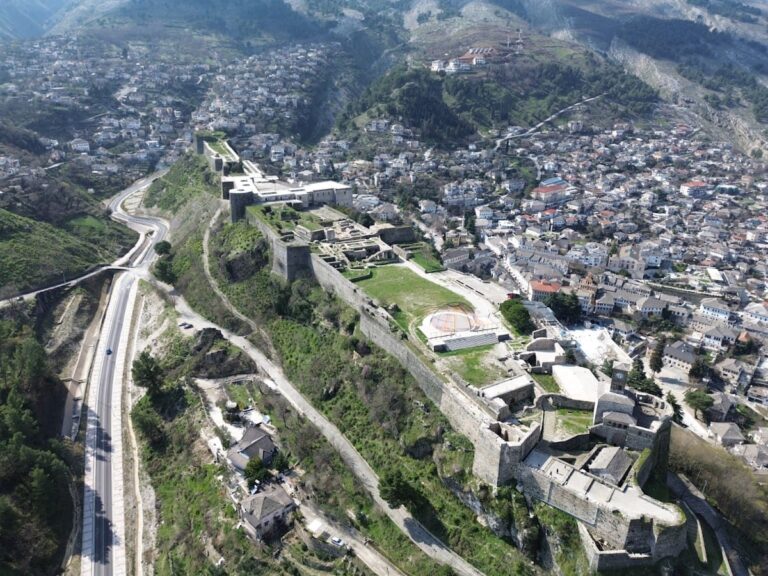

The Archaeological Park of Antigona is located near the contemporary city of Gjirokastër in southern Albania, within the administrative region designated as 6017. The site occupies a commanding position atop a rocky hill approximately 600 meters above sea level, overlooking the Drino River valley. This elevated terrain provided natural defensive advantages and strategic oversight of the surrounding fertile plains and mountain passes, facilitating control over regional movement and trade routes.

The local landscape is characterized by limestone formations and accessible water sources, factors that influenced the initial settlement and sustained occupation of the site. Archaeological evidence demonstrates that Antigona was established during the Hellenistic period and continued to be inhabited through the Roman era, reflecting a succession of cultural influences from Illyrian to Greek and Roman traditions.

History

Hellenistic Period (3rd century BC)

Antigona was founded circa 295 BC by Pyrrhus of Epirus, the Molossian king, who named the city after his wife Antigone, herself connected to the Ptolemaic dynasty through her mother Berenice I. The city’s location on a hill approximately 600 meters high allowed it to dominate the Drino valley and control critical mountain passes leading to the Ionian coast. This strategic siting underscored its military and administrative importance within the Molossian kingdom and the broader Hellenistic geopolitical landscape.

As one of the largest urban centers in present-day Albania, Antigona encompassed roughly 45 hectares within its fortified perimeter, with fortification walls extending about 4,000 meters in length. The city’s urban plan adhered to the Hippodamian orthogonal grid system, featuring wide paved streets with sidewalks and rainwater drainage channels. Public architecture included a western agora bordered by a stoa, serving as a civic and commercial hub, and an additional stoa outside the southern gate, likely functioning as a marketplace for rural producers. Suburban fortifications at Lekli, Labova, and Selo protected the wider Drinos Valley, indicating the city’s role in regional defense and territorial control.

Political and Military History in the Hellenistic Era

Throughout the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, Antigona was enmeshed in the complex military conflicts of the Hellenistic period. In 230 BC, Illyrian forces under Scerdilaidas traversed the area during campaigns in the region. During the Second Macedonian War (200–197 BC), the city allied with Macedon under Philip V. Macedonian forces, commanded by General Athenagoras, occupied nearby mountain passes to impede Roman advances. Despite initial resistance, Roman troops overcame these defenses, aided by local betrayals, culminating in the defeat of a Macedonian contingent of approximately 2,000 soldiers.

Following Rome’s decisive victory over Macedon in 167 BC, the Roman consul Aemilius Paullus ordered the systematic destruction of seventy towns in Epirus, including Antigona. The city was burned and abandoned, marking the cessation of its prominence as a Hellenistic urban center. This act was part of Rome’s broader strategy to suppress regional resistance and consolidate imperial control over the western Balkans.

Roman Period and Late Antiquity (2nd century BC – 6th century AD)

Despite the Roman destruction in the late 2nd century BC, archaeological evidence attests to a degree of reoccupation at Antigona during late antiquity. The site remained inhabited from the 4th through the 6th centuries AD, although documentary sources from this period are scarce. A significant discovery is a small early Christian triconch church dating to the 5th or 6th century AD, situated on the southern edge of the former fortified area. This ecclesiastical building features a nave with auxiliary chambers and a polychrome mosaic floor divided into three thematic sections, including a central human figure with an animal head, marine motifs, and vine imagery.

Architectural fragments such as marble, stucco, and painted plaster were recovered from the church. The structure represents the last known ancient construction at the site and was destroyed during Slavic incursions in the 6th century, reflecting the broader instability and demographic shifts affecting Epirus during this period. The decline in urban complexity and the shift toward ecclesiastical leadership illustrate the transformation of Antigona from a fortified city to a smaller, Christianized community.

Medieval and Later Periods

Following the decline of the ancient city, the site experienced limited medieval activity. Archaeological remains include a small church dating to the 9th or 10th century AD, located at a principal crossroads within the former urban grid. This suggests some continuity or adaptive reuse of the ancient infrastructure by a reduced rural population maintaining Christian worship. Additionally, a post-medieval church dedicated to St. Michael stands atop the highest hill, known as the Acropolis, indicating sporadic religious use of the site’s elevated terrain in later centuries.

During the medieval period, the settlement no longer functioned as an urban center but rather as a minor religious locale within a fragmented landscape. The population likely engaged in subsistence agriculture and pastoralism, with social organization centered on ecclesiastical authority. This trajectory reflects the long-term decline from a major Hellenistic and Roman city to a sparsely inhabited rural area with intermittent sacred significance.

Archaeological Rediscovery and Modern Research

The precise identification of Antigona remained uncertain until the 1970s, when Albanian archaeologist Dhimosten Budina conducted excavations that uncovered bronze and silver voting tokens inscribed with the city’s name, conclusively confirming the site’s identity. Subsequent archaeological investigations revealed the city’s street grid, fortifications, public buildings, and domestic quarters, establishing its historical and cultural significance.

Today, the site is designated as a National Archaeological Park encompassing approximately 90 hectares. Ongoing Albanian-Greek collaborative research continues to explore and preserve the site. Noteworthy artifacts, including a bronze sphinx figurine and a statue of Poseidon, have been conserved and are exhibited in museums in Tirana. Conservation efforts focus on stabilizing extant structures and mitigating environmental degradation, thereby supporting both scholarly study and controlled public engagement with the site’s heritage.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Hellenistic Period (3rd century BC)

The population of Antigona during its founding period was predominantly Molossian Greek, with cultural and dynastic ties to the Ptolemaic dynasty through Queen Antigone. Archaeological evidence suggests a heterogeneous community that included Greek settlers alongside indigenous Illyrian groups, reflecting a blend of cultural traditions. Social stratification likely featured an elite class engaged in governance and military leadership, supported by artisans, merchants, and agricultural workers forming the broader citizenry.

Residential architecture commonly comprised peristyle houses with central courtyards surrounded by colonnades, providing both domestic and workspaces. Excavations have identified specialized workshops within the city, including facilities for leatherworking, weaving, and coachmanship, the latter evidenced by the discovery of an iron chariot wheel. The economy was diversified, with agriculture flourishing in the fertile Drino valley; staple foods likely included bread, olives, wine, and fish, as suggested by mosaic iconography and regional analogies.

The agora and its bordering stoa functioned as focal points for commerce and social interaction, where rural inhabitants brought produce and crafts for sale. The city’s infrastructure supported transport and trade, with paved roads facilitating movement of goods and military forces. Clothing styles conformed to Hellenistic norms, featuring woolen tunics and cloaks worn with leather sandals. Public and private spaces were adorned with mosaic floors and painted plaster, while religious life centered on Greek polytheism, with civic rituals presumably conducted in the agora and sanctuaries, although no major temples have been identified.

Political and Military History in the Hellenistic Era

The city’s civic and social life was profoundly affected by regional conflicts, particularly during the Second Macedonian War. Military mobilization and the presence of Macedonian forces under Philip V introduced a militarized dimension to society, with local elites aligned to external powers. The eventual Roman conquest and destruction of Antigona in 167 BC abruptly terminated its urban functions, displacing inhabitants and dismantling established civic institutions.

Roman Period and Late Antiquity (2nd century BC – 6th century AD)

Following the Roman destruction, Antigona’s population contracted but did not disappear entirely. Archaeological evidence indicates a smaller, localized community persisted into late antiquity, adapting to the shifting political and religious landscape. The construction of an early Christian triconch church in the 5th or 6th century AD marks a significant religious transformation, with Christian ecclesiastical structures supplanting earlier civic and pagan functions.

The church’s mosaic floor, featuring symbolic imagery such as a human figure with an animal head and marine motifs, reflects evolving theological iconography and an active Christian congregation. Economic activity during this period was modest, likely centered on subsistence agriculture and small-scale crafts. The absence of large public buildings or fortifications suggests a decline in urban complexity. Domestic spaces became simpler, with fewer decorative elements than in the Hellenistic era. Social organization shifted toward ecclesiastical leadership, with clergy assuming roles formerly held by civic magistrates. The destruction of the church during Slavic incursions in the 6th century signals the end of significant occupation at the site.

Medieval and Later Periods

During the medieval era, the site experienced intermittent reoccupation, as evidenced by a 9th–10th century church located at a main crossroads within the former urban grid. This indicates limited continuity or reuse of the ancient infrastructure by a small rural community maintaining Christian worship. The post-medieval church of St. Michael on the Acropolis hill further attests to sporadic religious activity on the site’s elevated terrain.

Daily life in this period was predominantly rural and subsistence-based, with inhabitants engaged in agriculture and pastoralism rather than urban commerce or administration. Housing was modest, reflecting the reduced population and resources. Social structures centered on ecclesiastical authority, with the church serving as a focal point for community identity and ritual. The site’s regional significance had diminished considerably, no longer functioning as a city or fortified center but as a minor religious locale within a fragmented medieval landscape.

Remains

Architectural Features

Antigona is situated on a rocky hill rising to approximately 600 meters above sea level, with the northern summit reaching 700 meters. The ancient settlement covers an estimated 60 hectares within and beyond its fortified perimeter, while the entire archaeological park extends over approximately 90 hectares. The city was enclosed by substantial limestone fortification walls measuring around 4,000 meters in length, 3.5 meters in thickness, and up to 3 meters in height. These walls were constructed from large and medium-sized limestone blocks quarried from the nearby Lunxhëria mountain. The southern section of the walls is the best preserved, terminating near the early Christian triconch church. A prominent city gate remains visible on the southwestern wall segment. The highest hill, known as the Acropolis, is connected to the main settlement by a 4-meter-wide corridor flanked by parallel walls, forming a controlled access route.

The urban layout follows a Hippodamian orthogonal grid plan, with parallel north-south and east-west streets. The main north-south roads are wider, featuring broad sidewalks and visible rainwater drainage channels. The principal thoroughfare, named after archaeologist Dhimosten Budina, measures approximately 6 meters in width and extends at least one kilometer from the northern to the southern city gates. Streets bordered residential blocks (insulae) and terminated at the city gates. Suburban fortifications protected the wider Drinos Valley, including outlying fortresses at Lekli to the north, Labova to the east, and Selo to the south.

Key Buildings and Structures

City Walls and Gates

The city’s defensive walls date to the early Hellenistic period, constructed in the late 4th to early 3rd century BCE. Built primarily of large limestone blocks, the walls form a continuous circuit around the hilltop settlement. The southern end of the walls is the most intact, ending near the early Christian church. The southwestern gate remains the most visible entrance, featuring masonry consistent with the original fortifications. The walls’ substantial thickness and height indicate a primary military function, enclosing the urban area and regulating access. The corridor linking the Acropolis hill to the city is defined by two parallel walls approximately 4 meters apart, creating a controlled passageway.

Agora and Stoas

The agora, situated in the western sector of the city overlooking the Drinos Valley, functioned as the principal public square. It is bordered on the north side by a stoa—a covered promenade—dating to the 3rd century BCE, which constitutes the most significant public structure within the city walls. An additional stoa lies outside the southern gate, approximately 250 meters beyond the fortifications. This external stoa measures about 70 meters in length and features a polygonal bottom wall serving as a terracing structure. Its front is supported by pilasters constructed from stone blocks that upheld the roof. The external stoa likely operated as a marketplace where local villagers brought goods for sale. It forms the base of a long terracing wall extending to the southernmost city fortifications.

Domestic Buildings

Excavations have revealed several peristyle-type dwellings dating primarily to the Hellenistic period. These houses feature an inner courtyard surrounded by colonnades, with living and working spaces arranged around it. The lower walls were constructed of carved stone blocks, while the upper sections were likely built of adobe bricks, which have not survived. Some houses have been identified by archaeological finds related to specific trades, such as the currier’s house, the handloom weaver’s house, and the coachman’s house, where an iron chariot wheel was discovered. These structures illustrate the residential character and economic specialization within the urban quarters.

Early Christian Triconch Church

Located at the southernmost part of the fortified city area, this small church dates to the 5th or 6th century CE. It exhibits a distinctive triconch architectural form, comprising a nave with three semi-circular apses and auxiliary rooms on its sides. The altar area contains a well-preserved polychrome mosaic floor divided into three thematic sections with inscriptions. The central mosaic depicts a human figure with an animal head, interpreted as either the Egyptian god Anubis or Saint Christopher. The southern apse mosaic features marine motifs including fish, while the northern apse displays vine branches and a cantaloupe, common ecclesiastical decorative elements. Marble architectural fragments, stucco decorations, and painted plaster were also recovered. This church represents the last known ancient construction at the site and was destroyed during Slavic incursions in the 6th century CE.

Medieval Church (9th–10th Century)

Ruins of a small medieval church dating to the 9th or 10th century CE have been uncovered at a main crossroads within the former urban area. This structure was erected after the decline of the ancient city and reflects limited reuse of the site’s infrastructure during the early medieval period. The church’s remains are fragmentary but indicate continued Christian religious activity. Additionally, a post-medieval church dedicated to St. Michael stands on the highest hill, the so-called Acropolis, marking sporadic religious use of the elevated terrain in later centuries.

Monumental Tomb or Cistern

On the slope outside the city walls, a monumental structure dating to the 3rd–2nd centuries BCE has been identified. Constructed of framed stone blocks, it contains two communicating chambers accessed through two gates. Archaeologists have proposed two possible functions for this building: a monumental tomb or a cistern. The precise purpose remains undetermined, but the masonry and layout are consistent with Hellenistic funerary or hydraulic architecture.

Infrastructure: Roads and Drainage

The city’s road network adheres to the Hippodamian orthogonal plan, with paved streets and sidewalks. Several roads retain visible rainwater drainage channels, indicating an organized urban sanitation system. The main north-south road, approximately 6 meters wide, extends from the northern to the southern gates. Excavations have also revealed paved slabs, sewage water pipes, and a tunnel associated with one of the market buildings, demonstrating infrastructural complexity within the settlement.

Other Remains

Additional archaeological features include traces of a tunnel linked to a market building, numerous domestic artifacts, and fragments of architectural decoration scattered across the site. The abandoned village of Ladovishte, located a few hundred meters south of the city, contains a damaged and partially rebuilt church, indicating later settlement activity in proximity to the ancient site.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations at Antigona have yielded a diverse assemblage of artifacts spanning from the Hellenistic through the early medieval periods. Notable finds include bronze figurines such as a sphinx and a statue of Poseidon, both conserved and exhibited in Tirana museums. Bronze keys stamped with the city’s name “ANTIGONEIA” were uncovered; these are interpreted as voting tokens used by citizens, confirming the city’s identity. Silver voting cards bearing the city emblem have also been found. Iron chariot wheels and various bronze objects were discovered in domestic contexts, supporting evidence of specialized economic activities.

Pottery debris is widespread across the site, indicating active production and trade during the city’s peak. Architectural fragments such as marble pieces, stucco, and painted plaster were recovered, particularly from the early Christian church. These finds collectively document the city’s material culture and economic life from the 3rd century BCE through late antiquity and into the medieval period.

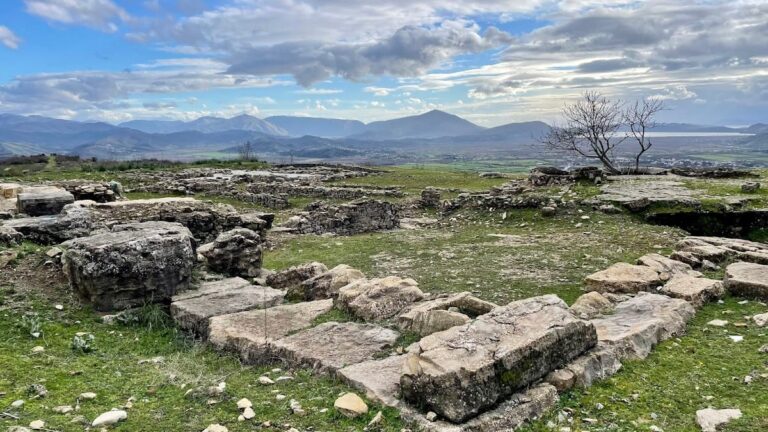

Preservation and Current Status

The city walls remain partially preserved, with the southern section best maintained. The southwestern city gate is visible but fragmentary. The early Christian triconch church retains significant architectural elements, including its mosaic floor and structural layout, though it is no longer intact. Domestic buildings survive mainly as foundations and lower wall courses, with upper structures lost due to the use of perishable materials. The agora and stoas are identifiable through their stone foundations and terracing walls.

Conservation efforts have focused on stabilizing exposed masonry and protecting the site from environmental degradation. Some areas have been cleared of vegetation to prevent damage, while others remain in situ without reconstruction. Ongoing Albanian-Greek collaborative research continues to monitor and preserve the site. The archaeological park is managed to balance research needs with preservation, though some structures remain vulnerable to erosion and human impact.

Unexcavated Areas

Significant portions of the site remain unexcavated, particularly in the suburban zones and the wider territory protected by outlying fortifications. Surface surveys and geophysical studies suggest buried remains beneath the modern landscape, but detailed excavation has been limited. The Acropolis hill, while containing the post-medieval church of St. Michael, lacks evidence of a classical acropolis and remains largely unexplored archaeologically. Future excavations are planned but constrained by conservation policies and the need to preserve the site’s integrity.