Kaiserthermen Trier

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.4

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.trier-info.de

Country: Germany

Civilization: Roman

Remains: Sanitation

History

The Kaiserthermen are located in Trier, Germany, and were constructed by the Romans during the late 3rd and early 4th centuries AD. This large bath complex was initiated before 300 AD to serve the public and to honor Caesar Constantius Chlorus and his son Constantine, who made Trier their residence. Construction likely stopped around 316 AD due to political conflicts, leaving the baths unfinished and never fully used as intended.

In the late 4th century, under Emperors Gratian and Valentinian II, the incomplete baths were converted into a cavalry barracks for the imperial mounted guard, known as the scholares. The hot bath, or Caldarium, may have served as a flag sanctuary and exercise hall during this time.

After Roman rule ended around 400 AD and the Gallic praetorian prefecture moved away, the site saw limited use in the early Middle Ages. By the 6th century, the inner area was likely fortified and used as a castle, with large windows blocked and replaced by arrow slits for defense.

During the High Middle Ages, between 1102 and 1124, the ruins were incorporated into Trier’s city fortifications under Archbishop Bruno of Lauffen. The site became the southeastern bastion of the city walls, featuring a city gate called Altport. A parish church dedicated to St. Gervasius existed there from at least 1101, and a convent church named St. Agneten was established in 1295, along with residential and craft buildings.

Over the centuries, much of the stone was removed from the site, but the core area survived due to its military and religious uses. The castle on the site was destroyed in 1015, and the city gate remained until 1817, when it was closed during archaeological clearing efforts.

Archaeological excavations began in the early 20th century, between 1912 and 1914, revealing the site’s original function and layout. Major excavations from 1960 to 1966, led by Wilhelm Reusch, focused on the western residential blocks and the bath complex. Restoration and conservation work took place in the 1980s, including stabilizing and partially reconstructing the Caldarium.

Since 1986, the Kaiserthermen have been part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Trier. The site is protected under German heritage law, and a museum building designed by Oswald Mathias Ungers was added to display archaeological finds and provide information.

Remains

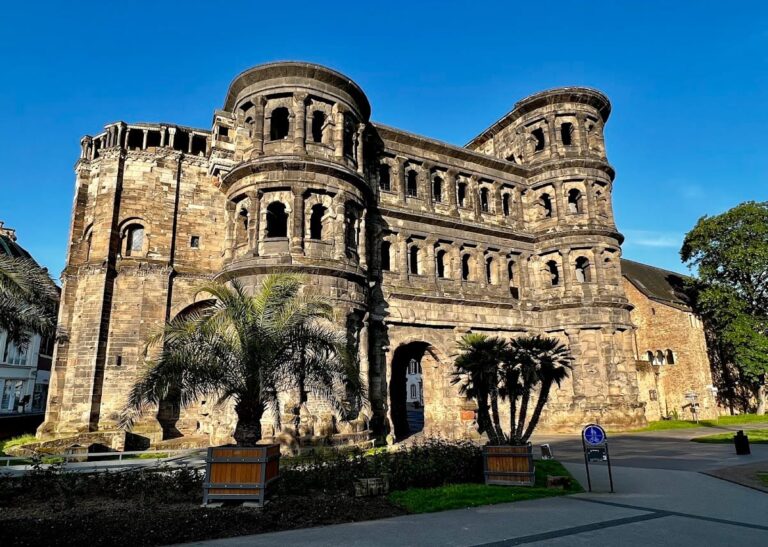

The Kaiserthermen cover an extensive area measuring approximately 250 by 145 meters. The complex is arranged symmetrically along a central axis and was built with massive walls reaching up to 19 meters high. These walls consist of carefully cut limestone blocks alternating with brick bands, enclosing a core of Roman concrete known as opus caementicium.

The most impressive feature is the large Caldarium, or hot bath, which includes a huge central apse facing southeast. This apse has large windows to admit light, an unusual orientation compared to typical Roman baths. The Caldarium rises over several stories and remains well preserved.

Next to the Caldarium is a circular Tepidarium, or warm bath, topped by a dome with a diameter of 16.45 meters made from Roman concrete. The planned Frigidarium, or cold bath, would have been the largest open-span hall but was never finished and was later demolished during the military conversion.

The western entrance features a richly decorated portal about 20 meters wide with three doorways. This leads into a rectangular hall with a large semicircular apse that may have housed a nymphaeum, a decorative water feature. Beyond this hall lies a large palaestra, or exercise yard, covering about 20,980 square meters and surrounded on three sides by a covered walkway.

The palaestra was bordered by changing rooms and sanitary facilities. The complex included extensive hypocaust heating systems, which are underground furnaces and channels that circulated warm air to heat the floors and walls. Service corridors ran beneath the baths for maintenance and water supply, some planned as two-story but never completed.

During the military conversion, the frigidarium was demolished, and the western underground galleries were filled in. The Caldarium and Tepidarium became the core of the barracks’ headquarters. A smaller, fully functional military bath was built west of the Caldarium, featuring a peristyle courtyard, cistern, and typical bath rooms such as the apodyterium (changing room), frigidarium with a cold-water basin, tepidarium with heating, and caldarium with a hot-water basin.

The barracks were protected by a massive semicircular defensive wall on the east side, enclosing a space over 20 meters wide around the Caldarium. The site also contains remains of four urban blocks, or insulae, that predate the baths. These include residential buildings from the early and middle imperial periods, such as a large house with a peristyle courtyard decorated with mosaics showing charioteers, and a small rotunda with four rounded apses.

Today, the core bath structures, especially the Caldarium, are well preserved and partially restored. Other parts have been lost due to medieval construction, stone robbing, and modern interventions. The site functions as an archaeological park with a modern visitor center.