Apollonia Archaeological Site: An Ancient Greek and Roman City in Albania

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.6

Popularity: Very Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Country: Albania

Civilization: Byzantine, Greek, Roman

Remains: City

Context

The Archaeological Museum of Apolonia is situated near the contemporary village of Pojan in Fier County, southwestern Albania. The site occupies a fertile plain adjacent to the Vjosë River, which historically provided essential water resources and supported agricultural activities. Its proximity to the Adriatic Sea positioned Apolonia at a strategic nexus linking inland Balkan routes with maritime corridors, facilitating economic and cultural exchanges across the region.

Founded in the 6th century BCE by Greek settlers from Corinth and Corcyra (modern Corfu), Apolonia developed through successive Classical, Hellenistic, and Roman phases. It later became integrated into the Roman province of Macedonia and experienced continued occupation into Late Antiquity. Archaeological evidence indicates a gradual decline during the early Byzantine period, with abandonment likely occurring by the 6th or 7th century CE.

Systematic excavations initiated in the early 20th century have uncovered extensive remains of public architecture, fortifications, and artifacts. The site’s preservation benefits from sediment burial and limited modern urban encroachment. The museum houses a significant collection of finds from these excavations, and ongoing conservation efforts aim to safeguard the ruins and advance scholarly research into Apolonia’s multifaceted historical development.

History

Apollonia’s historical significance derives from its location at a critical crossroads connecting the Adriatic coast with the interior Balkans. Initially inhabited during the Early Bronze Age by Illyrian groups associated with the Adriatic-Ljubljana cultural complex, the site later became a prominent Greek colonial foundation. Over time, Apollonia evolved through Classical, Hellenistic, and Roman periods, reflecting broader political, economic, and cultural transformations in the western Balkans. Its eventual decline in Late Antiquity corresponds with environmental and geopolitical shifts, culminating in abandonment by the early Byzantine era.

Pre-Foundation and Early Bronze Age

Prior to Greek colonization, the area of Apollonia was situated along a prehistoric trade route linking the eastern Adriatic coast with the Balkan interior and the northern Adriatic with the Aegean Sea. Archaeological evidence includes burial mounds (tumuli) dating from circa 2850 to 2500 BCE, attributed to Illyrian populations of the Adriatic-Ljubljana culture, which shares affinities with the Cetina culture and exhibits influences from the Early Cycladic I culture of southern Greece. Surface surveys suggest the region was sparsely occupied, likely by seasonal Illyrian pastoral groups organized in tribal systems. The discovery of mid-7th century BCE Corinthian pottery in the hinterland and within tumuli indicates pre-colonial trade contacts between Greek and Illyrian communities, although no permanent indigenous settlements immediately preceding the Greek foundation have been identified.

Greek Colonization and Archaic Period (circa 600–5th century BCE)

Apollonia was founded around 600 BCE by approximately 200 Corinthian colonists under the leadership of the oikist Gylax, possibly in cooperation with settlers from Corcyra. The foundation likely occurred with the consent of local Illyrian tribes, notably the Taulantii. The colony was established on a largely abandoned coastal site featuring a riverine harbor on the Aoös (Vjosë) River, facilitating trade both inland and along the Adriatic coast. Corinthian colonial policy at Apollonia was comparatively inclusive, permitting coexistence and cultural exchange with indigenous Illyrians. Osteological analyses reveal low levels of skeletal trauma, and evidence of intermarriage suggests social integration between Greeks and Illyrians.

Over time, Apollonia attained political autonomy from Corinth, developing as an oligarchic polis governed by descendants of the original Greek colonists, while the majority population remained Illyrian. The city expanded territorially around 450 BCE by conquering the Illyrian settlement of Thronion, thereby acquiring fertile lands and control over bitumen mines near Selenicë. Apollonia emerged as a significant trade gateway linking the Adriatic port of Brundusium (modern Brindisi) with northern Greece and the central Balkans, serving as the western terminus of the Via Egnatia. The city minted its own coinage from the 5th century BCE, featuring iconography such as a cow suckling her calf, with coins found as far as the Danube basin.

Classical and Hellenistic Period (5th–3rd century BCE)

During the Classical and Hellenistic periods, Apollonia experienced substantial demographic growth and urban expansion, with population estimates reaching up to 60,000 inhabitants at its zenith. The city maintained a narrow oligarchic government dominated by Greek elites descended from the founding colonists, while the majority Illyrian population likely occupied subordinate social roles, including serfdom or slavery. The aristocracy preserved strong cultural ties to Corinth, maintaining Greek personal names, traditions, and religious practices. Apollonia implemented xenelasia, a policy of expelling foreigners considered detrimental to public welfare, paralleling Spartan customs.

The city’s economy prospered through agriculture, slave trade, and exploitation of local asphalt resources used for maritime applications such as ship caulking. Archaeological remains include a late 6th-century BCE stone temple outside the city, one of only a few known in present-day Albania. In the later Hellenistic period, the urban economy shifted toward a dispersed farmstead model, though the nature of this expansion—whether by conquest, assimilation, or cooperation with indigenous groups—remains a subject of scholarly debate. Apollonia also came under the influence of Pyrrhus of Epirus during the early 3rd century BCE.

Roman Period (229 BCE–4th century CE)

Apollonia came under Roman control in 229 BCE, becoming a loyal ally and strategic military base during Rome’s campaigns against Illyrian and Macedonian rulers. The city served as a key staging ground during the Fourth Macedonian War, notably under Roman praetor Lucius Anicius Gallus, who was supported by Illyrian troops from the Parthini tribe. By the 3rd century BCE, Illyrians began to occupy prominent civic and military positions within the city, signaling a gradual cultural assimilation and transformation of its original Greek colonial character.

In 148 BCE, Apollonia was incorporated into the Roman province of Macedonia and later became part of Epirus Nova. The city supported Julius Caesar during the Roman civil wars but was captured by Marcus Junius Brutus in 48 BCE. Around 44 BCE, Gaius Octavius (the future Emperor Augustus) studied philosophy, rhetoric, and military training in Apollonia under the tutelage of Athenodorus of Tarsus, receiving news of Caesar’s assassination there. Augustus subsequently granted the city privileges that reinforced its oligarchic institutions in alignment with Roman governance. Under Roman rule, Apollonia flourished culturally and economically, with Cicero describing it as a “great and important city” (magna urbs et gravis).

Christianity was established early in the city, with bishops from Apollonia attending the First Council of Ephesus in 431 CE and the Council of Chalcedon in 451 CE. The city was part of the Illyrian provinces in the 6th century CE, as recorded in the Synecdemus of Hierocles. However, a significant earthquake in the 3rd century CE altered the course of the Aoös River, causing the harbor to silt up and the surrounding area to become marshy and malarial. These environmental changes contributed to Apollonia’s decline and abandonment by the 4th century CE, with the nearby settlement of Avlona (modern Vlorë) rising in prominence.

Late Antiquity and Early Christian Period

Following the urban decline, Apollonia persisted as a smaller Christian community centered around the church of the Dormition of the Theotokos (Shën Mëri), later incorporated into the Ardenica Monastery complex. The city functioned as a bishopric from approximately 400 CE until its suppression around 599 CE. Bishops from Apollonia participated in major early Christian councils, including those at Ephesus and Chalcedon. The episcopal see was a suffragan of the archbishopric of Dyrrachium. Despite the city’s diminished status, the monastery hosted a Greek language school providing higher education by the late 17th century and continued with limited activity into the 19th century.

Medieval Period and Monastic Legacy

During the medieval period, the monastery of Shën Meri was established within the ruins of Apollonia, with the main church (katholikon) dating to the 13th century, possibly under the reign of Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos. The monastery complex includes a refectory, a tower base, and monks’ living quarters, reflecting architectural influences from both Byzantine and Western Romanesque traditions. Frescoes within the refectory depict biblical scenes with stylistic elements reminiscent of the Italian Renaissance, indicating cultural exchanges in the region. The monastery’s architecture exemplifies the Balkan borderland’s blend of Eastern Orthodox and Western Christian artistic and religious traditions.

Archaeological Rediscovery and Modern History

Apollonia was rediscovered by European scholars in the 18th century, with systematic archaeological investigations commencing in the early 20th century. Austrian teams conducted early excavations during World War I, followed by French missions between 1924 and 1938, which uncovered major public buildings including the stoa, bouleuterion, odeon, library, gymnasium, and temples. The site sustained damage during World War II and further destruction in 1967 due to military construction of concrete bunkers. The Archaeological Museum of Apolonia was established in 1958 within the monastery complex to house finds from excavations. Although plundered during the political turmoil of the 1990s, the museum reopened in 2011 with support from UNESCO. Recent excavations have revealed a 6th-century BCE Greek temple and Roman statues, including a bust of a Roman soldier. Despite these efforts, only about 5% of the site has been excavated, and it remains a focus of ongoing international archaeological research. In 2003, the Albanian government designated the ruins as an archaeological park. The site suffered vandalism during the 2020 COVID-19 lockdown, damaging ancient columns that were subsequently restored.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Greek Colonization and Archaic Period (circa 600–5th century BCE)

The foundation of Apollonia introduced a structured urban community characterized by a mixed Greek-Illyrian population. The ruling class consisted predominantly of Greek settlers and their descendants, who governed an oligarchic polis, while the majority Illyrian inhabitants engaged primarily in pastoralism and agriculture within this framework. Gender roles likely conformed to Greek norms, with men dominating public and political spheres and women managing domestic affairs, though evidence of intermarriage suggests some cultural blending.

Economic activities centered on agriculture, including grain cultivation and animal husbandry, supplemented by exploitation of natural resources such as bitumen. The riverine harbor on the Aoös (Vjosë) facilitated trade inland and along the Adriatic, connecting Apollonia to Corinth and other Greek markets. Artisans produced pottery, including Corinthian-style wares, and coinage minted from the 5th century BCE indicates economic autonomy and regional trade reach. Domestic architecture likely featured simple layouts with courtyards and storage rooms; while direct evidence is limited, parallels with contemporary Greek colonies suggest use of painted pottery and modest furnishings.

Religious practice involved worship of Greek deities, with a notable late 6th-century BCE stone temple outside the city indicating organized cult activity. Social customs included taxation of Illyrian pastoralists for grazing rights, reflecting economic integration. Political institutions comprised magistrates descended from the original colonists, though inscriptions naming officials are scarce from this period. Apollonia functioned as a strategic trading polis and cultural intermediary between Greek and Illyrian worlds.

Classical and Hellenistic Period (5th–3rd century BCE)

During this period, Apollonia expanded significantly in population and urban complexity, reaching an estimated 60,000 inhabitants. The social hierarchy remained sharply divided: a Greek oligarchic elite controlled political offices and citizenship, while the majority Illyrian populace likely occupied subordinate roles, including serfdom or slavery. Family structures adhered to Greek patriarchal norms among the elite, with evidence of xenelasia policies indicating social exclusivity. The city’s aristocracy maintained Greek cultural traditions, including personal names and religious festivals.

Economic activities diversified and intensified. Agriculture remained foundational, with dispersed farmsteads emerging in the hinterland, though the exact nature of their integration with indigenous populations is debated. Apollonia prospered through slave trade, agriculture, and exploitation of local asphalt deposits used for maritime purposes. Workshops and small-scale production of pottery and textiles likely operated within households or specialized quarters. Diet included cereals, olives, wine, and fish, consistent with regional Mediterranean patterns. Domestic decoration advanced, as seen in mosaic floors and painted walls in elite villas such as the House of Athena, which featured mythological motifs.

The city’s public architecture flourished, with monumental buildings like the bouleuterion, odeon, and stoa serving as centers for political, cultural, and philosophical life. Religious observance focused on Greek deities, with temples and ritual spaces supporting festivals and communal worship. Apollonia’s civic role solidified as a major regional trade hub and oligarchic polis, controlling fertile lands and resource-rich territories. Its political institutions and coinage underscored autonomy and integration into wider Hellenistic networks, including intermittent subordination to powers like Pyrrhus of Epirus.

Roman Period (229 BCE–4th century CE)

Under Roman dominion, Apollonia transitioned from a Greek colonial polis to a municipium within the provinces of Macedonia and later Epirus Nova. The population became increasingly mixed, with Illyrians rising to prominent civic and military positions, reflecting gradual cultural assimilation. Roman citizenship and local oligarchic governance coexisted, with inscriptions attesting to magistrates and duumviri maintaining city administration. Family life incorporated Roman customs alongside lingering Hellenistic traditions, and Christianity emerged early, evidenced by bishops attending major councils in the 5th century CE.

The economy thrived on agriculture, trade, and resource exploitation, though the 3rd-century CE earthquake and subsequent environmental changes severely impacted the harbor and surrounding lands. Urban households featured elaborately decorated villas with mosaics and frescoes, while public buildings such as the library, gymnasium, and theaters supported education and cultural activities. Apollonia hosted a renowned school of philosophy and rhetoric, attracting students including the future Emperor Augustus, who studied under Athenodorus of Tarsus. Markets offered a variety of goods, both local and imported via the Via Egnatia and Adriatic routes, with transport relying on riverine vessels and overland caravans.

Religious life evolved with the establishment of Christian communities, churches, and episcopal structures subordinate to Dyrrachium. Pagan cults declined but left architectural and artistic legacies. Apollonia’s strategic importance as a military base and trade center diminished after the harbor silted, leading to economic contraction and population decline. Nevertheless, it remained a significant urban center within the Roman imperial framework until its gradual abandonment in the 4th century CE.

Late Antiquity and Early Christian Period

Following urban decline, Apollonia persisted as a smaller, predominantly Christian settlement centered around the church of the Dormition of the Theotokos (Shën Mëri). The population was reduced and more rural in character, with ecclesiastical authorities such as bishops playing key roles in community leadership. Family and social structures adapted to a monastic and clerical milieu, with limited evidence of secular elites. The bishopric’s participation in early Christian councils indicates continued religious significance.

Economic activities focused on sustaining the local population, with agriculture and small-scale crafts supporting daily needs. The monastery complex became a focal point for education, hosting a Greek language school by the late 17th century, suggesting continuity of intellectual traditions rooted in earlier philosophical schools. Religious practices centered on Christian liturgy and monastic observance, with the church serving as a social and spiritual hub.

Apolonia’s civic role shifted from a polis to a bishopric and monastic center, reflecting broader Late Antique transformations. The site’s diminished political importance contrasted with its enduring religious and educational functions, maintaining cultural links to Byzantine ecclesiastical structures despite declining urban infrastructure.

Remains

Architectural Features

By the 4th century CE, Apollonia encompassed approximately 81 hectares, enclosed by defensive walls extending between three and four kilometers in length and measuring about three meters in thickness. These fortifications, constructed primarily of large stone blocks using ashlar masonry, were maintained and partially rebuilt during the 6th century CE under Emperor Justinian I, reflecting ongoing defensive concerns. The city’s urban layout centered on a large agora surrounded by public, religious, and residential structures, with two prominent hilltops hosting sacred precincts. Architectural styles exhibit a blend of Classical Greek and Roman influences, with later Byzantine modifications. The urban fabric reveals phases of expansion during the Classical and Hellenistic periods, followed by contraction and partial abandonment in Late Antiquity. Many buildings were repurposed or fell into disuse by the early Byzantine era.

Key Buildings and Structures

City Walls

The city walls primarily date to the Classical and Hellenistic periods, enclosing the urban area with a circuit approximately three to four kilometers long. Constructed of large stone blocks, the walls are about three meters thick and incorporate towers and gates, though only fragmentary remains survive. Renovations under Justinian I in the 6th century CE attest to their continued strategic importance during Late Antiquity.

Temenos and Temple of Apollo

The sacred precinct (temenos) occupies one of the two main hills overlooking the city. Central to this area is the Temple of Apollo, a Doric temple constructed in the 6th century BCE from local Karaburun stone. The temple is oriented east–west and is surrounded by retaining walls added in the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE. The temenos also includes two stoas (covered colonnades), a Greek theater, and a nymphaeum (ornamental fountain). Architectural and cultural features within the temenos indicate coexistence and cultural fusion between Greek colonists and local Illyrian populations.

Buleuterion

The Buleuterion, serving as the city council building, is located near the Agora in the city center. Constructed during the Roman period, it incorporates the Agonothetes monument, erected in the late 2nd century CE to commemorate two contest judges, as indicated by an inscription. The Buleuterion was restored in 1976 by Albanian archaeologist Koco Zhegu. Architecturally, it shares construction techniques with the nearby library, featuring ashlar masonry and a rectangular plan.

Library

Situated at the eastern end of the Agora, the library dates to the Roman period. It is a quadrangular building constructed with masonry techniques similar to those of the Buleuterion. Its precise function remains uncertain due to the absence of definitive inscriptions or internal features. The structure is partially preserved, with foundations and some wall segments extant.

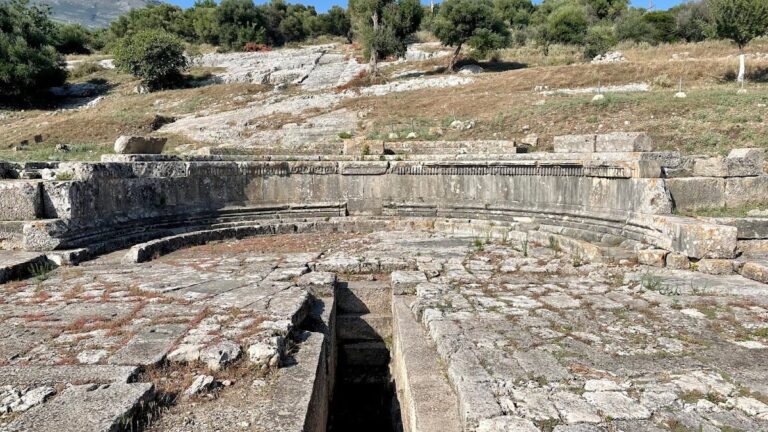

Odeon

The Odeon lies on the north side of the Agora and was built in the mid-2nd century CE, combining Greek architectural style with Roman construction methods. It features sixteen rows of semicircular seating, accommodating approximately 300 spectators. Attached to its west wall is a small sanctuary measuring five by five meters, likely serving ritual functions related to Odeon events. This sanctuary includes two Ionic columns on its facade and bases for three statues near the altar.

Temple of Diana

Located west of the Buleuterion, the Temple of Diana was constructed in the late 2nd century CE. A marble statue of Diana found within the temple indicates her veneration as goddess of the hunt, moon, birth, and protector of women and girls. The temple’s remains include foundations and partial wall segments built with local stone and Roman masonry techniques.

Prytaneion

The Prytaneion, the seat of the city’s leading magistrates (prytaneis), is situated just behind the Buleuterion near the Agora. Its west-facing facade was adorned with marble columns topped by Corinthian capitals. Excavations in 1960 uncovered eleven statues dating to the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, confirming the building’s administrative function. The remains include foundations, column bases, and some decorative elements.

Theater

The theater is located approximately 300 meters north of the Agora. Its construction involved excavating a hillside and building an artificial dam on the northwest side for structural support. Dating to the Hellenistic period, the theater was abandoned in Late Antiquity. Stones from the seating rows were repurposed for the construction of the nearby Shën Meri monastery church. The seating area (cavea) and orchestra remain partially preserved. A German-Albanian archaeological team has conducted studies to understand the theater’s design and local architectural variants.

Nymphaeum

The nymphaeum ruins lie about 400 meters north of the theater. Discovered in 1962, this large, richly decorated drinking fountain was fed by an underground water source that still flows today. Built in the 3rd century BCE, it was in use for roughly a century before being buried by a landslide. Surviving elements include stone basins, decorative niches, and water channels.

Gymnasion

The gymnasion was constructed in the 6th century BCE and is located south of the city center along the road connecting the South Gate with the Agora. It remained in use until the 3rd century CE and underwent several reconstructions. The structure includes open courtyards and covered porticoes, with foundations and some wall segments preserved.

Great Stoa (Stoa B)

The Great Stoa is situated directly in front of the Odeon, leading toward the Agora. Dating to the Classical period and used until the mid-2nd century CE, it features 36 octagonal Doric columns dividing the walkway into two parallel paths. It possibly had a second story decorated with Ionic columns. The hillside-facing wall contains 14 niches that served as supports and display spaces for sculptures of ancient philosophers, some dating to the 2nd century CE. The stoa functioned as a covered public walkway and meeting place for philosophical debates and civic discussions.

Doric Temple (Unnamed)

Outside the city walls near the South Gate are remains of a Doric temple built around 480 BCE from local Karaburun stone blocks. The deity worshiped is unknown, but a statue found on site suggests a sea-related god, possibly Poseidon, Aphrodite, or Hermes. The temple’s foundations and some column drums survive.

Arch of Triumph

A marble-decorated triumphal arch stands at the entrance to the Agora. The monument measures approximately 14 meters in length and 10 meters in height. It features four columns and three arched gates. Decorative elements include carved reliefs and inscriptions, though some details are fragmentary.

House of Athena

The House of Athena is the largest known villa in Apollonia, covering about 3,500 square meters. It contains two peristyle courtyards and was built in the 2nd century CE. The eastern part of the villa features floors decorated with mosaics depicting Greek mythological figures. One mosaic shows a naked Nereid riding a dolphin surrounded by seahorses, while another depicts combat scenes between Achilles and Penthesilea. The villa was abandoned by the 3rd century CE. Structural remains include walls, mosaic floors, and column bases.

Villa with Impluvium

Near the gymnasion lies a villa constructed between the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, featuring an atrium with an impluvium (rainwater basin). Archaeological finds inside include a portrait of a philosopher, a headless Athena statue in the Promachos style, and a statue of the Titan Atlas carrying the heavens. The Atlas statue is now housed in the National Historical Museum in Tirana. In 2010, a bust of a Roman aristocrat was discovered in this area. The villa’s remains include foundations, mosaic fragments, and architectural elements.

Monastery of Shën Meri (Dormition of the Theotokos)

Constructed on a nearby hill after the city’s abandonment, the monastery church dates to the 13th century, possibly linked to Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos. The katholikon (main church) has a cross-in-square plan with a domed nave, narthex, and exonarthex. The exonarthex features a colonnade with capitals decorated with sirens, animals, and monsters, reflecting Romanesque influences. Frescoes inside depict Byzantine imperial family members and biblical scenes such as the Deposition and Archangel Gabriel. The refectory is triconch in plan with apses on three sides and decorated with Roman-Byzantine frescoes illustrating scenes like the Wedding at Cana and Washing of the Feet. The monastery complex also includes a tower base and monks’ living quarters. The architecture reflects a blend of Eastern Byzantine and Western Romanesque traditions.

Other Remains

Near the temenos, storehouses and cisterns dating to the 3rd century BCE are preserved. Two small sanctuaries, labeled A and B, from the 1st century BCE have been identified within the sacred area. Residential quarters contain numerous Hellenistic and Roman buildings with well-preserved mosaics. An archaic fortification and tumular necropolis from the Iron Age are present near the city, indicating earlier occupation phases. These remains, though fragmentary, contribute to understanding the city’s spatial organization and historical development.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations at Apollonia have yielded a diverse assemblage of artifacts spanning from the Early Bronze Age through Late Antiquity. Pottery includes Corinthian Greek wares from the 7th century BCE, local Illyrian ceramics, and Roman tableware. Numerous coins minted by Apollonia from the 5th century BCE onward have been found, some circulating as far as the Danube basin. Inscriptions include dedicatory texts on public buildings and monuments, such as the Agonothetes inscription on the Buleuterion. Tools related to agriculture and craft production have been recovered, alongside domestic objects like lamps and cooking vessels. Religious artifacts include statuettes, altars, and ritual vessels from the temenos and sanctuaries. Finds derive from public spaces, domestic quarters, and burial contexts, reflecting diverse aspects of urban life.

Preservation and Current Status

The preservation of Apollonia’s ruins varies across the site. The Great Stoa and parts of the Buleuterion and Odeon remain relatively well-preserved, with standing columns and wall segments. The Temple of Apollo and other religious structures survive primarily as foundations and partial walls. Sections of the city walls are visible but fragmentary. The theater’s seating area is partially preserved, though much was dismantled for later construction. The monastery of Shën Meri retains substantial architectural elements and frescoes. Restoration efforts include the 1976 rehabilitation of the Buleuterion and the 2011 renovation of the Archaeological Museum housed within the monastery complex. The site has suffered damage from military construction in 1967 and looting during the 1990s. Conservation continues under Albanian heritage authorities with international support.

Unexcavated Areas

Only approximately five percent of Apollonia’s total area has been excavated. Large portions of the city, including residential districts, economic quarters, and sections of the fortifications, remain unexcavated. Surface surveys and geophysical studies indicate the presence of buried remains beneath sediment and modern agricultural land. Some areas are restricted due to conservation policies or current land use. Future excavations are planned but constrained by funding and preservation considerations. The site’s designation as an archaeological park since 2003 aims to protect unexcavated zones while facilitating ongoing research.