Berat Old Town and Castle: A Multi-Period Cultural and Historical Site in Albania

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.7

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Country: Albania

Civilization: Byzantine, Ottoman, Roman

Remains: City

Context

Berat Old Town and its castle are situated in south-central Albania, within the contemporary municipality of Berat. The site occupies a prominent rocky hill rising approximately 214 meters above the Osum River valley, providing commanding views over the surrounding fertile plains and karstic hills. This topographic prominence afforded significant defensive advantages and control over the river corridor, a key route through the region.

The surrounding landscape’s agricultural potential supported sustained human occupation, with fertile soils enabling cereal cultivation and animal husbandry. The site’s location at the crossroads of Balkan cultural and political spheres contributed to its long-term strategic importance. Archaeological evidence documents continuous settlement from the Illyrian period through Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman eras, reflecting adaptation to shifting political and cultural influences.

Berat’s historic urban fabric includes substantial remains of fortifications, religious buildings, and residential quarters. Archaeological investigations initiated in the 20th century have revealed stratified occupation layers and architectural modifications corresponding to successive historical phases. Preservation efforts by Albanian heritage authorities have focused on stabilizing the castle walls and conserving the old town’s distinctive architectural character, underscoring Berat’s significance as a multi-period archaeological and cultural site.

History

Berat Old Town and its castle represent a site of enduring strategic and administrative significance in the southern Balkans. Its elevated position overlooking the Osum River valley made it a focal point for military control and regional governance from antiquity through the Ottoman period. The site’s continuous occupation, spanning Illyrian, Roman, Byzantine, medieval Balkan, and Ottoman phases, illustrates its role as a fortified settlement and administrative center within evolving imperial and local political frameworks.

Throughout its history, Berat experienced numerous military confrontations, administrative realignments, and demographic changes. Archaeological and historical sources document its transformation from an Illyrian stronghold to a Roman municipium, a Byzantine frontier fortress, a contested medieval city, and an Ottoman provincial center. The site’s layered remains encapsulate the complex interplay of cultural continuity and political change characteristic of the Balkan region.

Illyrian and Ancient Macedonian Period (7th century BCE – 2nd century BCE)

Archaeological findings, including ceramics dating to the 7th century BCE, attest to an Illyrian settlement on the rocky hill of Berat, identified with the ancient city of Antipatreia. Located within the borderland region of Dassaretia, this settlement occupied a strategic position contested by Illyrian tribes and Macedonian rulers. Following Cassander of Macedon’s consolidation of southern Illyria circa 314 BCE, Antipatreia likely underwent urban development and fortification enhancements, reflecting Macedonian influence.

Roman historian Livy describes Antipatreia as the largest settlement in the area, fortified with substantial walls and classified as an urbs, indicating its prominence beyond a mere oppidum or castellum. The city was a contested site during the Illyrian and Macedonian Wars, notably in 217 BCE when Illyrian dynast Skerdilaidas and Macedonian king Philip V vied for control. In 200 BCE, Roman legatus Lucius Apustius captured the city by force, executing military-aged men, plundering, demolishing its walls, and burning the settlement. Subsequently, Antipatreia was incorporated into the Roman province of Macedonia, within the district of Epirus Nova, marking a shift to Roman administrative structures.

Roman Period (2nd century BCE – 3rd century CE)

Under Roman dominion, Antipatreia maintained its strategic importance as a fortified municipium within the province of Macedonia. Its location along the Osum River corridor ensured continued military and administrative relevance. Archaeological evidence indicates expansion and reinforcement of defensive walls consistent with Roman provincial security policies. Although direct epigraphic attestations are limited, the settlement likely fulfilled municipal functions aligned with Roman urban models.

Roman architectural influence is evident in construction techniques and urban planning elements, though no large-scale public buildings have been definitively identified at the site. The local economy expanded through intensified agriculture, exploiting the fertile surrounding plains for cereals, olives, and vineyards. Small-scale workshops probably produced pottery, metal goods, and textiles, supporting both local needs and regional trade. Religious life integrated Roman and indigenous cults, although specific temples or shrines remain undocumented. The city’s role was primarily that of a fortified municipal center contributing to regional stability within the imperial system.

Late Antiquity and Byzantine Period (3rd century – 14th century)

Following the Western Roman Empire’s decline, the city—referred to as Pulcheriopolis in early Byzantine sources—became part of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire’s frontier zone. This era was characterized by repeated Slavic incursions and political instability, reflecting broader challenges to Byzantine authority in the Balkans. Defensive fortifications were strengthened under Emperor Theodosius II in the 5th century and rebuilt by Justinian I in the 6th century, underscoring the site’s continued military significance.

In the 9th century, the First Bulgarian Empire under Presian I captured the city, which acquired the Slavic name Belgrad (“White City”), a designation that persisted throughout the medieval period. The city became a key center within the Bulgarian region of Kutmichevitsa before its reconquest by Byzantine Emperor Basil II in 1018. During the 12th and 13th centuries, Berat experienced fluctuating control among the Second Bulgarian Empire, the Despotate of Epirus, and the Serbian Empire. Notably, Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos successfully defended the city against a Sicilian siege in 1280–1281. The fortress was further fortified in the 13th century under Michael I Komnenos Doukas, Despot of Epirus.

In the early 14th century, Berat remained a contested stronghold amid Albanian tribal uprisings and imperial campaigns. It passed to the Serbian Empire in 1345 and subsequently to local rulers such as John Komnenos Asen and Balsha II until the late 14th century. The castle housed numerous Byzantine-era Orthodox churches, many adorned with frescoes by the 16th-century painter Onufri, reflecting the site’s religious and cultural prominence during this period.

Ottoman Conquest and Early Ottoman Period (1385 – 17th century)

Berat was captured by the Ottoman Empire in 1385, serving as a strategic foothold for further Ottoman expansion in the Balkans. Initially, the Albanian Muzaka family governed the city as the capital of the Principality of Berat until its full incorporation into the Ottoman administrative system in 1417. The fortress and town functioned as important military and administrative centers during this transitional phase.

In 1455, the Albanian leader Skanderbeg led an unsuccessful siege against the Ottoman garrison, which was defended by a force of approximately 40,000 soldiers against his 14,000 troops. The 16th century witnessed demographic and economic decline, with records indicating only 710 houses by the late 1500s. However, the 17th century saw a revival, with Berat emerging as a center for crafts, particularly wood carving.

Religious demographics shifted notably during this period. Early 16th-century records show a predominantly Christian population, with no Muslim households recorded between 1506 and 1583. A small Sephardic Jewish community, composed of families expelled from Spain, was present around 1520. By the late 16th century, the Muslim population increased substantially due to conversions and migration, influenced by Ottoman policies granting tax exemptions to Muslim craftsmen in exchange for military service. By 1670, Muslims constituted the majority in most neighborhoods, reflecting significant social and religious transformation.

Ottoman Era and Pashalik of Berat (18th – 19th centuries)

In the 18th century, Berat attained prominence as the capital of the Pashalik of Berat under Ahmet Kurt Pasha, marking its status as a key political and administrative center within Ottoman Albania. Following the defeat of Ibrahim Pasha of Berat by Ali Pasha in 1809, the city was incorporated into the Pashalik of Yanina. In 1867, Berat was designated a sanjak center within the Janina vilayet, replacing Vlorë as the provincial capital. The influential Albanian Vrioni family dominated the city’s political and economic life during this period.

The 19th century saw a revitalization of Berat’s Jewish community, supported by connections with the Jewish population of Yanina. A Greek-language school operated from 1835, reflecting the city’s multicultural and multilingual character. The population ranged between 10,000 and 15,000, including a significant Orthodox Christian minority, many of whom spoke Aromanian. Berat played an active role in the Albanian national awakening, with Christian merchants supporting nationalist movements. The city experienced revolts in 1833 and 1839 demanding Albanian administration and exemption from Ottoman conscription, leading to temporary concessions. Berat was also a center of support for the League of Prizren in the late 19th century, participating in broader efforts for Albanian autonomy.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Illyrian and Ancient Macedonian Period (7th century BCE – 2nd century BCE)

The earliest inhabitants of Berat, associated with the Illyrian city of Antipatreia, lived in a fortified settlement atop the rocky hill. Social organization likely centered on tribal elites overseeing extended family units, with men responsible for defense and warfare, as indicated by the substantial fortifications described by Livy. Women managed domestic affairs and agricultural support, consistent with Illyrian societal norms. The settlement functioned as a regional stronghold controlling access along the Osum River valley.

Economic activities focused on subsistence agriculture, including cereal cultivation and animal husbandry, supported by the fertile surrounding plains. Archaeological finds such as ceramics suggest local pottery production for household use. Trade and craft specialization were limited but facilitated by the city’s position on regional routes. Diet likely included grains, olives, fruits, meat from livestock, and fish from the river. Clothing consisted of wool and linen tunics and cloaks typical of Illyrian and Macedonian populations. Domestic architecture is poorly documented but probably included fortified houses with courtyards and storage facilities.

Roman Period (2nd century BCE – 3rd century CE)

Following Roman conquest, Antipatreia evolved into a municipium with enhanced administrative functions. The population comprised Roman settlers and indigenous Illyrian descendants, with local elites cooperating with Roman officials. Social hierarchy included artisans, farmers, and soldiers. Family structures adhered to Roman patriarchal norms, with multi-room houses accommodating extended families, as inferred from comparable provincial towns.

Economic life expanded through intensified agriculture producing cereals, olives, and vineyards. Archaeological evidence indicates fortified walls and urban planning elements reflecting Roman architectural influence, though direct evidence of public buildings is limited. Local workshops produced pottery, metal goods, and textiles at household or small-scale levels. Diet incorporated bread, olive oil, wine, and fish, consistent with Roman provincial patterns. Trade connected Antipatreia to larger markets within Macedonia and Epirus Nova. Religious life integrated Roman and local deities, though specific cults remain undocumented.

Late Antiquity and Byzantine Period (3rd century – 14th century)

During the Byzantine era, the city—known as Pulcheriopolis and later Belgrad—remained a fortified urban center amid frontier instability. The population included Byzantine Greeks, Slavs, and Bulgarians, reflecting shifting political control. Social stratification encompassed military garrisons, clergy, local administrators, and civilians. Family life was influenced by Orthodox Christian norms, with ecclesiastical authorities playing increasing roles in community organization.

Economic activities adapted to frontier conditions, emphasizing local agriculture, animal husbandry, and crafts supporting the fortress and town. Strengthened walls under Theodosius II and Justinian I indicate continued military investment. Byzantine architectural styles influenced church construction, with numerous Orthodox churches built within the castle precinct, many richly decorated with frescoes by painters such as Onufri. Domestic interiors likely featured painted walls and modest furnishings. Markets and trade persisted locally, with goods including agricultural produce, textiles, and religious items. Transportation relied on foot and pack animals. Religious life centered on Orthodox Christianity, with churches serving as focal points for worship, education, and social gatherings. Civic administration involved Byzantine military governors and local elites.

Ottoman Conquest and Early Ottoman Period (1385 – 17th century)

Under Ottoman rule, Berat’s population became increasingly diverse, initially dominated by Christian Albanian families, with gradual Muslim settlement and conversion by the late 16th century. Social organization included Muslim military elites, Christian merchants, artisans, and a small Sephardic Jewish community. Gender roles conformed broadly to Ottoman Islamic and Balkan Christian norms, with men engaged in military, administrative, and craft occupations, and women managing households.

Economic life centered on crafts such as wood carving, metalworking, and textile production, often organized in guilds. Agriculture remained vital, with local markets supplying grains, olives, and fruits. The city’s decline in the 16th century reflected demographic contraction, but recovery in the 17th century saw artisanal specialization flourish. Shopping occurred in bazaars where imported and local goods mingled. Transportation relied on animal caravans and river routes. Religious practices were pluralistic: Sunni Islam predominated among ruling classes and converts, Orthodox Christianity persisted among the majority until the late 16th century, and the Jewish community maintained synagogues and institutions. Mosques such as the Sultan’s and Lead Mosques attest to Islamic religious life, while Orthodox churches served Christian worshippers. Sufi orders, notably the Halveti, contributed to spiritual and social life. The city functioned as a military-administrative center and craft hub within the Ottoman provincial framework.

Ottoman Era and Pashalik of Berat (18th – 19th centuries)

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Berat’s population included Muslims, Orthodox Christians (many Aromanian-speaking), and Jews, reflecting a multiethnic urban society. Social hierarchy featured pashas, wealthy merchants, religious leaders, artisans, and peasants. Family structures were patriarchal, with extended kin networks supporting trade and political alliances. Education included Greek-language schools and religious instruction in churches and synagogues.

The economy was diversified, with craft guilds producing leather goods, metalwork, silk, and wood carvings. Workshops operated at household and guild levels, supplying local and regional markets. Agriculture in surrounding plains supported urban consumption. Markets and bazaars offered imported and local goods, while the city’s role as a sanjak center fostered administrative employment. Transport involved horse-drawn carts and river crossings such as the Gorica Bridge. Religious life remained vibrant, with Orthodox churches, mosques, and synagogues serving their communities. The Orthodox Church played a central role in cultural identity and education, while Sufi tekkes provided spiritual guidance. Social customs included festivals and communal gatherings reflecting religious calendars. Berat was a focal point of Albanian national awakening, with civic leaders and merchants supporting political activism. The city’s administrative status as a pashalik capital and later sanjak center underscored its regional importance.

Remains

Architectural Features

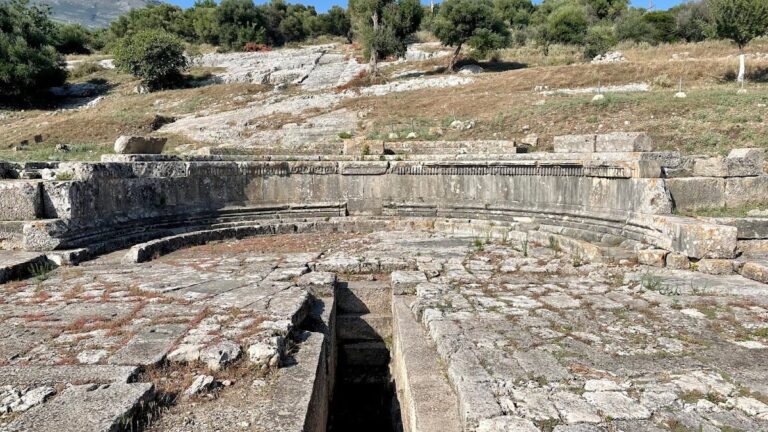

Berat Old Town and its castle occupy a rocky hill overlooking the Osum River valley at approximately 214 meters elevation. The fortress walls visible today primarily date from the 13th century, although the site’s origins extend to the 4th century BCE. The castle is accessible mainly from the south, with the principal entrance on the north side, protected by a fortified courtyard and three smaller gates. The defensive walls underwent multiple construction phases: originally destroyed by Roman forces in 200 BCE, reinforced in the 5th century CE under Emperor Theodosius II, rebuilt in the 6th century by Emperor Justinian I, and extensively reconstructed in the 13th century under Michael I Komnenos Doukas. The 13th-century phase is distinguished by a red brick monogram embedded in the walls.

The fortress encompasses an area sufficient to accommodate a significant portion of the medieval town’s population. Within the castle, numerous 13th-century buildings survive as cultural monuments, including residential quarters, religious structures, and military installations. The urban fabric reflects a fortified settlement with a predominantly Christian population during the Middle Ages. The surrounding fertile plains and karstic hills supported agricultural activities sustaining the inhabitants over centuries.

Key Buildings and Structures

Ottoman Residential Buildings (Domestic)

Several Ottoman-period houses remain within the old town, identifiable by their timber-framed upper stories projecting over stone ground floors. Walls are constructed of roughly dressed stone bonded with lime mortar, and roofs are covered with ceramic tiles. Interiors often include stone hearths and niches. These houses are arranged along narrow streets and courtyards, reflecting Ottoman urban design principles. Some buildings incorporate earlier Byzantine or Roman foundations reused in their construction. Preservation states vary from well-maintained to partially collapsed.

Berat Castle (Kalaja e Beratit)

Berat Castle is a fortified complex dating mainly from the 13th century, with origins in the 4th century BCE. Constructed of stone and brick, the castle walls enclose an area large enough to house a considerable segment of the town’s population. The main entrance on the north side is defended by a fortified courtyard and three smaller gates. The walls exhibit multiple construction phases: initial fortifications destroyed by Romans in 200 BCE, strengthened in the 5th century CE under Theodosius II, rebuilt in the 6th century by Justinian I, and extensively reconstructed in the 13th century under Michael I Komnenos Doukas. The 13th-century phase is marked by a distinctive red brick monogram embedded in the walls. In the mid-14th century, the castle was under the rule of John Komnenos Asen.

Inside the fortress, 13th-century buildings survive as cultural monuments. Defensive structures include thick stone walls, battlements, and towers designed to control access and provide protection. Only limited remains survive of the single mosque used by the Muslim garrison, including a few ruins and the base of its minaret. The castle’s Christian population constructed approximately 20 Orthodox churches within the walls, many of which have suffered damage over time, with only some still standing.

Churches inside Berat Castle

The castle contains about 20 Albanian Orthodox churches, primarily built in the 13th century. These religious buildings feature frescoes and carved wooden iconostases painted by notable Albanian iconographers such as Onufri, Kostandin Shpataraku, and the Zografi Brothers. The frescoes date from the Middle Ages and include distinctive elements like Onufri’s characteristic shiny red pigment known as “Onufri’s Red” and individualized facial expressions.

Notable churches include the Church of the Holy Trinity (14th century), constructed in a cross-shaped plan with Byzantine murals; the Church of St. Michael (13th century), located outside the ramparts and accessible via a steep path; and the St. Mary of Blachernae Church (13th century), which contains 16th-century murals by Nikollë Onufri, son of Onufri. The Church of St. Nicholas has been restored and now functions as a museum dedicated to Onufri. Other churches include St. Theodore, Saints Constantine and Helen, St. George, Evangelistria, and the Dormition of the Virgin Mary. These churches also contain religious silverwork such as sacred vessels, icon casings, and Gospel book covers. The Berat Gospels, dating from the 4th century, are preserved in the National Archives in Tirana.

Bachelors’ Mosque (Xhami e Beqareve)

Constructed in 1827, the Bachelors’ Mosque is located near the street descending from the fortress. It features a portico and external decorations depicting flowers, plants, and houses. The mosque is named after the “Bachelors,” young shop assistants who served as a private militia for Berat’s merchants.

King Mosque (Xhamia e Mbretit)

The King Mosque, the oldest mosque in Berat, was built during the reign of Bayazid II (1481–1512). It is notable for its finely decorated ceiling. The building currently functions as a museum.

Lead Mosque (Xhamia e Plumbit)

Constructed in 1555, the Lead Mosque derives its name from the lead covering of its cupola. It serves as the central mosque of Berat.

Halveti Tekke (Teqe e Helvetive)

The Halveti Tekke, associated with the Khalwati Sufi order, was originally built in the 15th century and rebuilt in 1782 by Ahmet Kurt Pasha. It is located near the purported grave of Sabbatai Zevi, an Ottoman Jew banished to Dulcigno (modern Ulcinj).

Gorica Bridge

The Gorica Bridge spans the Osum River and was originally constructed from wood in 1780. It was rebuilt in stone during the 1920s. The bridge features seven arches, measures 129 metres (423 feet) in length, 5.3 metres (17 feet) in width, and stands approximately 10 metres (33 feet) above the average water level. Local tradition holds that the original wooden bridge contained a dungeon where a girl was starved to appease protective spirits.

National Ethnographic Museum of Berat

Opened in 1979, the National Ethnographic Museum is housed in Berat and contains a collection of everyday objects from the city’s history. Exhibits include non-movable furniture, household items, wooden cases, wall-closets, chimneys, and a well. The museum displays an olive press, wool press, and large ceramic dishes illustrating historical domestic culture. The ground floor features a model of a medieval street with traditional shops, while the second floor contains an archive, loom, village sitting room, kitchen, and sitting room.

Other Remains

The fortress area contains the ruins of the single mosque used by the Muslim garrison, with only fragments and the base of the minaret surviving. Many of the churches inside the fortress have been damaged or destroyed over time, leaving only some standing today. The defensive walls show multiple construction phases, with visible masonry techniques including stone and brickwork. The red brick monogram from the 13th century remains embedded in the castle walls. No other major civic or domestic structures have been documented in detail within the fortress area.

Archaeological Discoveries

Archaeological investigations at Berat have uncovered stratified occupation layers spanning from the Illyrian period through Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman eras. Artifacts include numerous frescoes and iconographic paintings inside the castle churches, attributed to painters such as Onufri and his son Nikollë. These frescoes demonstrate medieval Albanian religious art styles and techniques.

Religious silverwork such as sacred vessels, icon casings, and Gospel book covers have been found within the churches. The Berat Gospels, dating from the 4th century, are preserved in the National Archives in Tirana. Pottery fragments, domestic objects, and tools have been recovered from various layers, though detailed catalogs of these finds are limited. Inscriptions recording the names of painters and donors provide epigraphic evidence of artistic activity. No extensive reports of coins, large-scale inscriptions, or monumental statuary have been published.

Preservation and Current Status

The 13th-century castle walls and internal buildings are generally well preserved, with some sections partially collapsed or damaged. Restoration efforts have stabilized the fortifications and maintained the historic urban fabric. The churches inside the castle have suffered damage over the centuries, with only a few remaining intact. The mosque ruins within the fortress survive only as fragments and the minaret base.

Conservation work by Albanian cultural heritage authorities has focused on preserving the 13th-century structures and frescoes. Some buildings have undergone restoration using original materials, while others are stabilized in situ without reconstruction. Environmental factors such as vegetation growth and erosion pose ongoing challenges. The site is protected as a cultural monument, with ongoing archaeological research contributing to its maintenance and understanding.

Unexcavated Areas

Several parts of Berat Old Town and its surroundings remain unexcavated or poorly studied. Surface surveys suggest the presence of buried remains beyond the castle walls, particularly in the Mangalem and Gorica quarters. No comprehensive geophysical studies or large-scale excavations have been reported for these areas. Urban development and conservation policies limit extensive excavation within the historic town.

Future archaeological work is planned to focus on stratigraphic analysis and preservation rather than large-scale excavation. The castle interior and immediate surroundings have been the primary focus of research, leaving peripheral districts less explored. No detailed plans for excavation of Roman or Illyrian layers outside the fortress have been published.