Tripolis near Buldan: An Ancient City at the Crossroads of Lydia, Phrygia, and Caria

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.6

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.pau.edu.tr

Country: Turkey

Civilization: Byzantine, Greek, Roman

Remains: City

History

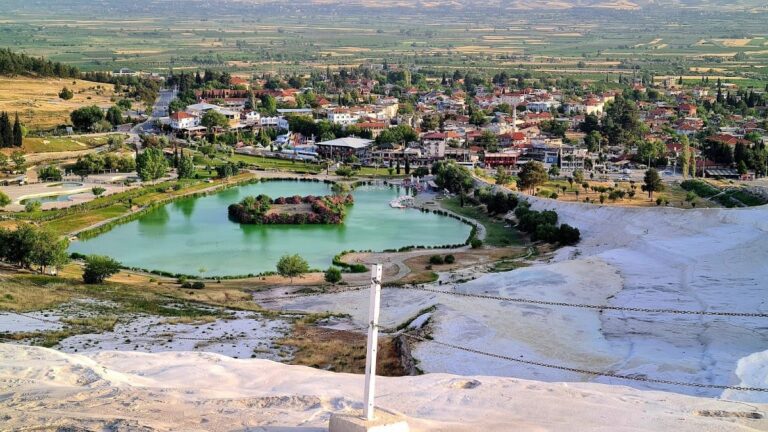

The ancient city of Tripolis is situated near the modern municipality of Buldan in Turkey. It was established by the Kingdom of Pergamon, creating a settlement at a strategic crossroads where the regions of Lydia, Phrygia, and Caria converged, close to the Maeander River. This location offered vital connections for trade and cultural exchange in antiquity.

During its early period, the city was known by several names including Tripolis ad Maeandrum, Neapolis, Apollonia, and Antoniopolis, reflecting its evolving identity and importance within the region. The city gained economic strength and political significance, minting its own coins that featured imagery of the goddess Leto, suggesting a local cult or patronage. Ancient writers such as Pliny the Elder, Ptolemy, and Stephanus of Byzantium mentioned Tripolis, each assigning it to different territorial affiliations, indicating its position on the margins of various cultural spheres.

In the 1st century BCE, Tripolis was ruled by a series of local tyrants known by name—Dionysius, Ptolemy, and Lysanius—who shaped the city’s political and social dynamics during a turbulent period. Following this era, the city endured multiple instances of destruction caused by natural disasters like earthquakes, as well as conflicts, particularly between the Byzantine and Turkish forces. These challenges ultimately led to the gradual decline and abandonment of the urban center.

Throughout the late Roman and Byzantine periods, Tripolis held religious importance as a bishopric under the metropolitan authority of Sardis. Known bishops from the city participated in major early Christian councils, such as the Council of Nicaea in 325 CE and the Council of Chalcedon, highlighting its ecclesiastical role in the region.

Archaeological interest in Tripolis began with modest excavations in 1993, initiated by the Denizli Museum Directorate. Later, more extensive and systematic digs were conducted by Ege University starting in 2007, paused in 2009, and then resumed in 2012 under the leadership of Pamukkale University. These excavations continue to reveal insights into the city’s prolonged occupation, uncovering structures from the Roman and Byzantine periods, including a monumental fountain dating back to the 2nd century BCE and an early Byzantine church approximately 1,500 years old.

Remains

The archaeological remains of Tripolis reveal a city initially designed with defensive considerations, later developed into a flourishing urban center during Roman and Byzantine times. The prevailing ruins stem largely from these later periods, offering a glimpse into the city’s layout and building techniques.

On the eastern side, Byzantine city walls stretch over 1,800 meters, constructed around the transition from the 4th to 5th centuries CE. These robust fortifications reach up to six meters in height and about 2.5 meters in width. Made from carefully dressed stone blocks and bricks, the walls incorporate reused architectural elements such as columns, capitals, friezes, and even bases of statues, demonstrating resourceful rebuilding practices. To the west, late Byzantine defenses extend across a preserved length of approximately 1,200 meters, featuring a fortress topped by a round tower built in the 13th century as protection against Turkish incursions.

Two principal city gates stood as key entrances. The southward Hierapolis Gate, dating to the mid-2nd century CE, once formed a striking marble arch supported by travertine columns; today, it remains mostly in ruins and overgrown. On the western approach, the Philadelphia Gate served as a gateway from roads leading to Phrygia and Sardis. Originally adorned with six columns and two arches, one of its columns still stands at 7.65 meters tall. This column has recently undergone conservation efforts to preserve its condition.

A central feature of the city was a long colonnaded street running 450 meters and measuring about 10 meters wide, creating the main artery of urban life. This street intersected at right angles with the Hierapolis street, which was paved with travertine slabs and incorporated drainage pipes beneath for managing sewage and rainwater. Along the colonnade’s southern side, an eight-meter-wide portico sheltered pedestrians, supported originally by thirteen wooden columns, six of which survive today. The floor beneath once boasted mosaic decorations, now largely fragmentary. Flanking the main street were six rooms that likely functioned as commercial shops.

At the junction of these main thoroughfares stood the Orpheus Fountain, a monumental nymphaeum on a marble platform. Its walls combined onyx and white marble, and it was supplied by terracotta pipes connected to a water reservoir situated east of the colonnaded street, illustrating advanced urban water management.

Two agoras have been identified, spaces traditionally used as marketplaces and public gathering spots. The northern agora covers close to 1,000 square meters and was once encircled by arcades held up by columns, though much of it lies beneath soil today. Another, from the late Roman period, retains eastern and western porticoes, hinting at continued civic use late into antiquity.

Burial grounds surrounded much of Tripolis. The northern hill contained rock-cut tombs, while the northeast sector harbored sarcophagi. In the southeast, early Byzantine barrel-vaulted tombs have been documented, showing continuity in funerary practices through different eras.

Public bathing was a significant aspect of social life, with at least two Roman baths identified from the 2nd century CE. Large baths near the western entrance included rooms arranged along a west-east axis, while another facility, known as the “theatrical baths,” lay adjacent to the city theater and oriented north-south. These baths drew water from nearby four-chambered cisterns, designed to ensure ample supply.

The theater itself, dating to the 2nd century CE, occupies a natural hill slope with a steep 50-degree incline and could seat up to 8,000 spectators. Much of it remains unopened to exploration, indicating potential for further discoveries. Northwest outside the walls, a stadium used for sporting and cultural events has been partially uncovered. Its running track is buried under approximately three meters of earth, yet western seating remains visible, with eastern sections showing signs of damage.

At the heart of civic administration stood the bouleuterion, the council building. Constructed from stone blocks and measuring about 64 by 44 meters, only sections of its walls remain above ground today.

Religious architecture is well represented by four early Byzantine churches adorned with colorful frescoes, offering insights into the city’s spiritual life during this later period. Remarkably, a covered market building—a rare example among ancient Mediterranean cities—has been unearthed in remarkable condition. Preserved by centuries of burial underground, this market demonstrates the complexity and endurance of urban commercial spaces in Tripolis.