Neratzia Fortress: A Historic Stronghold on Kos Island, Greece

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.2

Popularity: Low

Country: Greece

Civilization: Crusader, Ottoman

Site type: Military

Remains: Castle

History

Neratzia Fortress stands on the Greek island of Kos, within the municipality of Kos, Greece. It was constructed mainly by the Knights Hospitaller, also known as the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, following their acquisition of the island in 1314. The fortress’s early construction is believed to have begun under the leadership of Grand Master Helion de Villeneuve, with significant building efforts continuing from around 1377 during the tenure of Jean Fernandez de Heredia and extending into the early 1500s.

The fortress held a critical position guarding the harbor of Kos and overseeing maritime routes that linked Constantinople (modern Istanbul) with Alexandria in Egypt. Its strategic value was enhanced by its cooperation with another fortress located across the sea at St. Peter in Bodrum. Throughout its history, Neratzia underwent numerous fortification upgrades to respond to military threats, particularly from the expanding Ottoman Empire and the Mamluk Sultanate in Egypt. Among these improvements was the addition of bastions designed to resist advancements in artillery made possible by gunpowder.

The earliest known written mention of the castle dates to 1395 when the traveler Nicolo de Martoni described it as almost impregnable, due to its placement surrounded by sea and a nearby lake linked by a drawbridge. Despite its formidable defenses, the fortress faced several sieges, including one in 1457 when a large Ottoman force attacked it. On that occasion, defenders ultimately abandoned Neratzia to regroup their forces elsewhere. The fortress fell to the Ottomans in 1523 after the Knights were defeated at Rhodes, marking a significant shift in control of Kos.

Under Ottoman rule, Neratzia remained in military use, serving as both a garrison and the residence of the local governor. Structural changes during this period were limited, though a powerful explosion from a powder magazine in 1816 inflicted considerable damage inside the fortress. In the 20th century, when Kos came under Italian administration, efforts were made to restore the fortress to emphasize its medieval origins. Most Ottoman modifications were removed to better highlight the castle’s earlier character. During World War II, German troops utilized the fortress as a prison. In recent years, the fortress was temporarily closed following earthquake damage in 2017, before partially reopening in 2021.

Remains

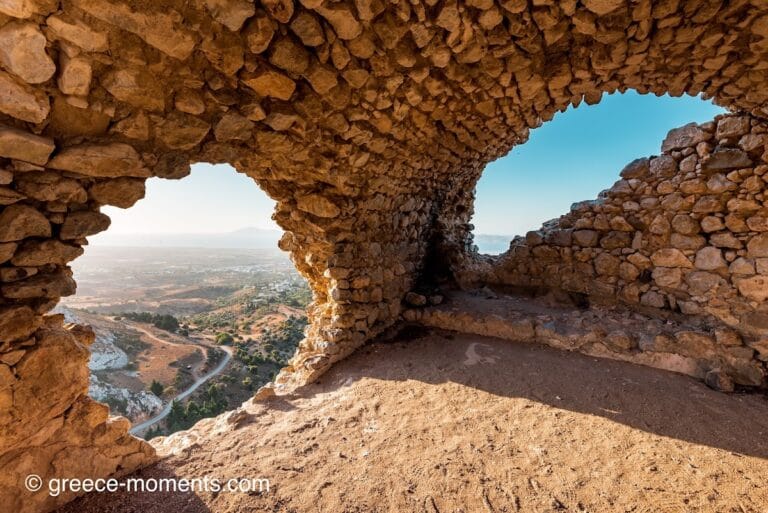

Neratzia Fortress occupies a narrow peninsula east of the Mandraki Harbor on Kos, originally standing as an island connected to the mainland by a stone bridge over a wide moat, which has since been filled in and replaced by a street. The fortress features an inner castle dating back to the 13th century, surrounded by later outer defensive walls constructed between the late 15th century and 1514. Together, these form an almost rectangular layout.

The central castle is marked by four tall, round towers positioned at its corners, supporting defensive efforts. Surrounding it, the outer walls were enhanced with large bastions—angular projections designed to better resist cannon fire—and equipped with cannon openings, reflecting the fortress’s adaptation to gunpowder weaponry. A broad moat, once approximately six meters deep and nearly 38 meters wide, separated the inner and outer fortifications, adding to its defensive strength.

Builders made extensive use of local stones including porous types in shades of green and softer varieties, as well as travertine, a form of limestone common in the Mediterranean. Notably, many architectural elements were repurposed from ancient structures on Kos and the nearby Asklepieion sanctuary, such as marble blocks, columns, altars, and fragments of carved stone. Decorative touches survive in the form of a marble frieze with garlands and theatrical masks above the main entrance, thought to originate from a temple dedicated to Dionysus, the god of wine and festivity. The walls and towers also bear carved coats of arms belonging to various Grand Masters of the Knights, including Emery d’Amboise.

The fortress’s main gate, once featuring two small towers that were removed in the early 20th century, was accessible via a stone bridge linking it to the mainland. Behind the gate, the interior resembles an open-air museum scattered with the ruins of ancient columns, graves, altars, and other stone carvings. No roofs or intermediate floor levels survive, and much of the interior is overgrown with thorny plants native to the region. One arched structure near the gate is a remnant from the Ottoman period, likely part of a water storage system.

A single sloping road provides a connection between the inner and outer sections of the fortress along its eastern side. Overall, the fortress displays a layered design that reflects its evolution over centuries, shaped by changes in military technology and the shifting needs of its defenders.