Castle of Castro Laboreiro: A Historic Fortress in Northern Portugal

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.6

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Country: Portugal

Civilization: Unclassified

Remains: Military

History

The Castle of Castro Laboreiro is located in the municipality of Melgaço in northern Portugal. Its origins trace back to prehistoric times, as the surrounding area features ancient megalithic monuments, indicating early human occupation long before recorded history.

During the Roman period, the site gained strategic importance due to its proximity to key roads and bridges spanning nearby rivers. In the early medieval period, specifically during the 9th and 10th centuries, King Alfonso III of Asturias granted control of the region to Count Hermenegildo as a reward for quelling a local rebellion. At that time, an existing fortified settlement, known as a castro, was transformed into a castle to strengthen territorial control. However, this fortress would later fall under Muslim rule during the region’s shifting political landscape.

The mid-12th century marked a turning point when Afonso Henriques, the first king of Portugal, reconquered the castle between 1141 and 1145. He reinforced its defenses, integrating it into the emerging Portuguese border fortifications. Further construction was completed under King Sancho I, who reigned from 1185 to 1211. Despite these efforts, the castle suffered severe damage in 1212 during an invasion by Leonese forces but was rebuilt around 1290 under King Denis of Portugal, who gave the fortress much of its present-day appearance.

From 1271 until the mid-19th century (1855), the castle served as the seat of local municipal government. Administratively, it belonged to the county of Barcelos until 1834 and was affiliated with the Order of Christ, a significant religious-military order, from as early as 1319. The castle’s military role continued into the 14th century when King John I used it as a stronghold against incursions from Castile coming from Galicia. During this period, the position of alcalde, or governor, was held by notable families such as the Gomes de Abreu, before King Ferdinand I granted it to Estevão Anes Marinho.

Political tensions occasionally surfaced within the castle’s administration, exemplified by the removal of alcalde Martim de Castro in 1441, following complaints from local inhabitants. In the early 1500s, the castle’s layout was documented in detailed drawings by Duarte de Armas, illustrating five quadrangular towers and a prominent central keep with a water cistern to the north.

In May 1666, the fortress was briefly captured by Baltazar Pantoja after a short but intense battle lasting four hours. It was soon recaptured by forces led by the 3rd Count of Prado. Although officially decommissioned after 1715, the castle remained in use in the late 18th century when the Count of Bobadela detained roughly 400 individuals inside its walls who had resisted military conscription.

During the early 19th century, specifically the Peninsular War around 1801, the castle was once again garrisoned and equipped with four artillery pieces. Despite this renewed military activity, the fortress was eventually abandoned and gradually fell into ruin. In recognition of its historical value, the Castle of Castro Laboreiro was officially classified as a National Monument in 1944. Subsequent archaeological surveys in the 1970s uncovered evidence of early medieval occupation, leading to restoration and consolidation efforts between 1979 and 1981. Later, in 2005, local authorities improved access to the site to support preservation efforts.

Remains

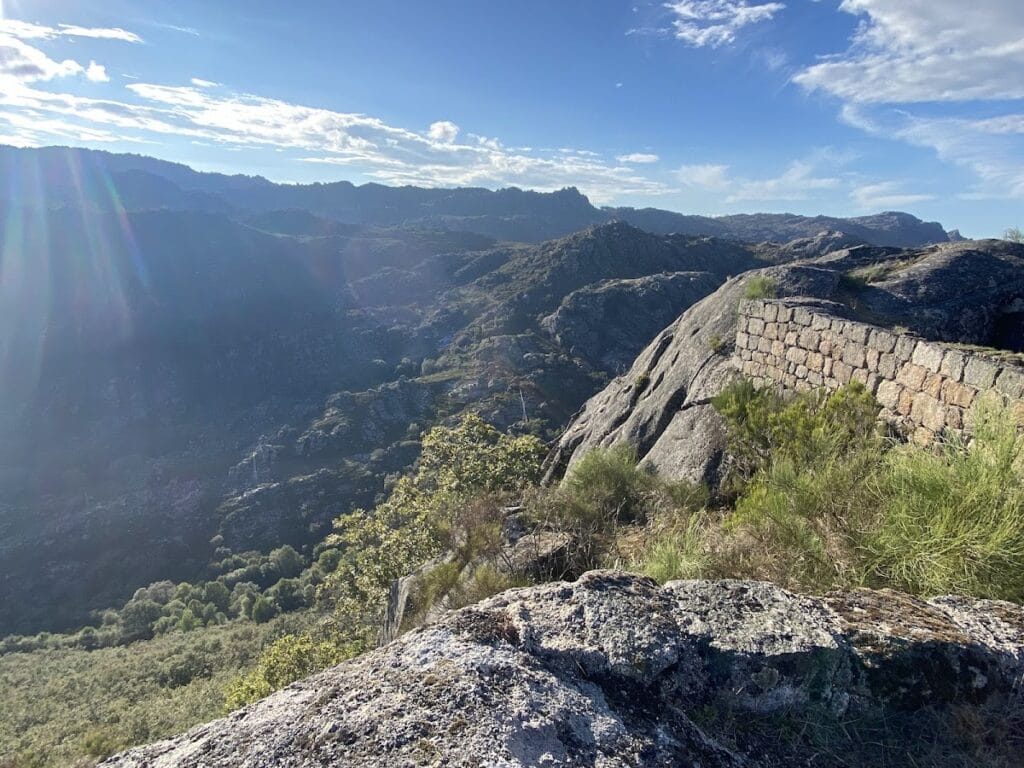

Perched atop a hill at an elevation of 1,033 meters, the Castle of Castro Laboreiro commands a dominant view over the landscape between the Minho and Lima river valleys, nestled within the Peneda-Gerês National Park. The fortress exhibits an oval-shaped layout that runs roughly from north to south, carefully shaped to conform to the rugged, rocky terrain. Its walls are built directly over cliffs and natural stone outcrops, following a zig-zag pattern in places that align with the foundations of former defensive towers.

The predominant architectural style of the castle combines Romanesque characteristics—common in medieval Europe—with later Gothic additions. This blend is visible in features such as small turrets and cubelos (cylindrical defensive structures) integrated into the walls of the alcáçova, the central enclosed area known as the citadel.

The stronghold is divided into two main sectors. To the north lies the military core, situated at a higher elevation. This area includes the quadrangular central keep, known as the tower of menagem, which stands surrounded by the main courtyard. Adjacent to this section is an ancient cistern located to the north of the keep, used historically to collect and store water within the fortress. This northern sector features two gates: the principal eastern entrance called Porta do Sol, or “Gate of the Sun,” and a secondary northern access known as Porta da Traição (“Gate of the Traitor”) or Porta do Sapo (“Gate of the Frog”).

The southern part of the castle forms a lower, secondary enclosure. Access to this space is granted via a full-arch bridge supported by stone piers, a distinctive architectural element. This southern enclosure was specifically designed to house livestock and valuable goods during times of attack, a defensive feature reflecting the importance of pastoral activities in the local economy. It stands as a unique example among Portuguese fortresses due to this specialized function.

Historical illustrations from the early 16th century depict the castle’s fortifications as reinforced by five quadrangular towers. These towers, including the main keep, exhibit a robust and angular design. The central keep itself is preceded by an additional structural element, possibly serving as a barrier or entrance feature.

Today, the remains of the castle include the ruins of the cistern, the layout of walls, towers, and gates, all preserved in a state of ruin but benefiting from cleaning and consolidation measures that protect the site from further decay. These surviving features provide insight into the castle’s adaptive architecture developed over centuries of military and administrative use.