Hofburg Palace Innsbruck: Historic Residence of the Habsburg Dynasty

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.4

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.hofburg-innsbruck.at

Country: Austria

Civilization: Unclassified

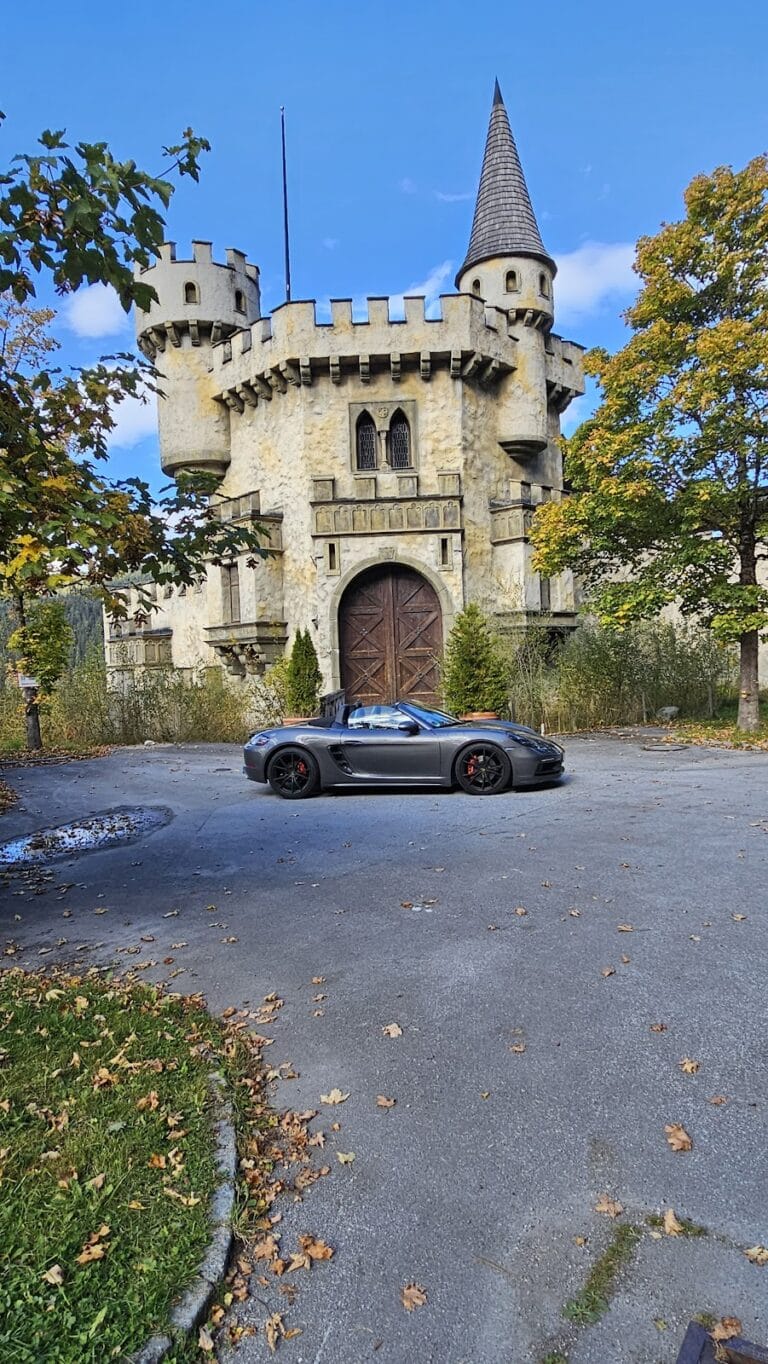

Remains: Military

History

The Hofburg palace is located in Innsbruck, a city in modern-day Austria. It was constructed by the Habsburg dynasty, a prominent European ruling family, who established it as a residence and seat of power in the region.

Construction of the palace began around 1460 under Archduke Sigismund, incorporating elements of medieval city defenses, notably parts of the old fortifications such as the Rumer Gate. This gate was transformed into the Heraldic Tower in 1499 by the artist Jörg Kölderer, commissioned during the reign of Emperor Maximilian I. Under Maximilian I’s rule in the late 15th century, the palace began evolving from its original medieval character, developing into a late Gothic residence reflecting the growing status of the Habsburgs.

After a destructive fire in 1534, the Hofburg underwent a Renaissance-style redesign led by the Italian architect Lucius de Spaciis under Emperor Ferdinand I. This reconstruction marked a significant transformation, introducing Italian Renaissance architectural principles into the building’s fabric. In the mid-18th century, Empress Maria Theresa commissioned a Baroque renovation that further reshaped the palace. This late phase of development reflected changing tastes and the desire to modernize the imperial residence.

The palace was the backdrop for important historical moments, including the sudden death of Emperor Francis I in 1765 during wedding celebrations at the Hofburg. The room where he passed away was converted shortly thereafter into the Hofburg Chapel, a sacred space commemorating his memory. During the early 19th century’s Napoleonic Wars, the palace temporarily housed King Maximilian I Joseph of Bavaria and briefly served as the headquarters of the Tyrolean resistance leader Andreas Hofer in 1809.

Throughout more than four centuries, the Hofburg remained a residence for various members of the Habsburg lineage, including Emperor Franz Joseph and the famed Empress Elisabeth. The last significant reorganization of the imperial apartments took place in 1858, inspired by the layout of Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna, aligning the interiors with contemporary standards of comfort and style. Over time, the complex expanded to include institutions such as the Noblewomen’s Collegiate Foundation, the Silver Chapel, the Hofkirche with its cenotaph honoring Emperor Maximilian I, and eventually the Tyrolean Folk Art Museum, illustrating the palace’s multifaceted role in regional cultural and religious life.

Remains

The Hofburg stands as an irregularly shaped complex covering around 5,000 square meters and containing approximately 400 rooms. Its design centers on a large rectangular courtyard paved with cobblestones, measuring roughly 1,300 square meters. This open space is surrounded by the wings of the palace and entered through four gateways. Decorative Baroque elements adorn the courtyard, including columns known as pilasters, cornices along the roofline, and ornamental cartouches featuring the Austrian striped shield, adding a sense of grandeur and imperial identity.

Integral to the original late Gothic palace structure were three medieval defensive features incorporated into the building: the South Roundel, originally known as the Rumer Gate and later called the Heraldic Tower; the North Roundel, a circular tower; and the Corner Cabinet, a rectangular tower situated at a corner of the complex. These fortifications are still visible in the façade, standing out as an uneven corner block that reflects their original defensive purpose.

Beneath the north wing lies the Gothic Hall, an expansive five-aisled space covering about 650 square meters. This vaulted hall features cross-shaped grooves formed by intersecting stone ribs, a hallmark of late medieval architecture, and is built with traditional brickwork of that period. While the western section remains in its original Gothic state, the southern and eastern portions were altered through the Renaissance and 18th-century renovations; notably, the eastern part once functioned as a kitchen, showing the hall’s adaptation over time.

In the mid-18th century, the south wing was rebuilt in the Baroque style under the direction of architect Johann Martin Gumpp the Younger (1754–1756). This renovation introduced new administrative offices, a grand central staircase, and uniform floor levels, alongside regularly spaced windows that contributed to a more harmonious exterior appearance. Following this, the main façade facing Rennweg Street was added between 1766 and 1773 by architects C. J. Walter and Nikolaus Pacassi. This façade features delicate Rococo decorations, which are characterized by ornate and elegant details.

Among the palace’s notable interior spaces is the Riesensaal, or Giants’ Hall, stretching approximately 31 meters in length. Originally serving as a banquet hall on the first floor during the expansions under Maximilian I, it now resides on the second floor. The ceiling is adorned with frescoes painted in 1775–1776 by Franz Anton Maulbertsch, depicting scenes from the myth of Hercules and portraits of Maria Theresa’s descendants, blending mythological and dynastic symbolism in a large decorative program.

The Hofburg Chapel, created in 1765–1766 in the very chamber where Emperor Francis I died, stands out as a long, rectangular two-story space. It features a flattened ceiling and is richly decorated in white and gold Rococo style. Among its artistic highlights are a large gilded cross, a painted relief by F. A. Leitensdorfer, and a sculptural altar group crafted by Anton Sartori, all contributing to its solemn and ornate atmosphere.

The palace includes two chapels; besides the Hofburg Chapel, the Silberne Kapelle (Silver Chapel) connects to the adjacent Hofkirche and houses a Renaissance organ, highlighting the link between sacred music and worship spaces within the complex.

Several imperial apartments retain original furnishings and décor spanning the 18th and 19th centuries. Among them are Maria Theresa’s Rooms, Empress Elisabeth’s Apartment with its silk textiles, and the Chinese Room featuring murals created in 1773 depicting Chinese motifs, which were restored after suffering damage during the Second World War. The Court Furniture Room displays finely crafted furniture produced by the Thonet company, renowned for its elegant bentwood pieces.

Rising prominently above the palace is the South Tower, also known as the Heraldic Tower, built around 1500. This tower is a well-known city landmark and is decorated with 56 painted coats of arms executed by Jörg Kölderer, serving as a visual record of noble lineages and alliances.

The Hofburg complex is carefully integrated into its surroundings, with spatial relationships extending to nearby historical places such as the Hofkirche, the Noblewomen’s Collegiate Foundation, and the Hofgarten, or Court Garden, together creating a coherent ensemble of imperial, religious, and cultural architecture in Innsbruck.