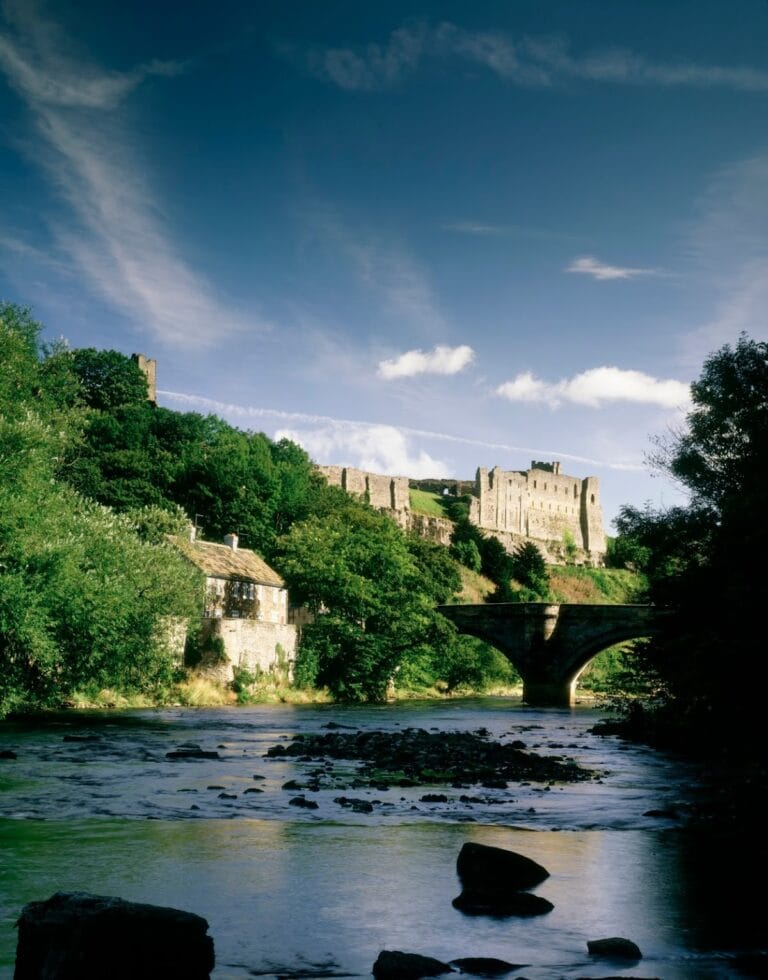

Middleham Castle: A Norman Stronghold in England

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.5

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.english-heritage.org.uk

Country: United Kingdom

Civilization: Medieval European

Remains: Military

History

Middleham Castle stands in the town of Middleham in England, built by the Norman civilization during the late 12th century. Its construction began around 1190 under Robert Fitzrandolph, the third Lord of Middleham and Spennithorne. The castle was established close to an earlier fortification known as William’s Hill, a motte and bailey castle that relied on timber defenses.

During its earliest phase, Middleham Castle was intended to guard the main road linking Richmond to Skipton, as well as the surrounding Coverdale area. This strategic position contributed to its importance through the medieval period. In 1270, the property passed into the hands of the Neville family, a powerful noble lineage. Among them, Richard Neville, the 16th Earl of Warwick and a central figure in the Wars of the Roses, is particularly notable.

In the 15th century, Middleham Castle gained further prominence when Richard, Duke of Gloucester—who later became King Richard III—was raised there under Warwick’s guardianship. After marrying Anne Neville, Richard made the castle his principal residence. Their only son, Edward of Middleham, was born and died within its walls towards the end of that century. Following Richard III’s defeat and death at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, the castle came under the control of Henry VII and was maintained as royal property for over a century.

In 1604, during King James I’s reign, Middleham Castle was sold to Sir Henry Linley, who undertook repairs and resided there until his death in 1610. Subsequently, the estate changed ownership again when the Wood family acquired it in 1662. Throughout the mid-17th century, the castle played a modest military role during the English Civil War; it was garrisoned between 1654 and 1655, hosting around thirty men and some prisoners, though no battles are recorded at the site. Notably, a 1644 parliamentary order declared the castle indefensible and recommended that no troops be stationed there.

By the late 17th century, Middleham Castle had fallen into decline. Its stonework was repurposed for local building projects, leading to significant deterioration. In the 20th century, efforts to preserve the ruins culminated in the site coming under the care of English Heritage in 1984. Today, the castle remains a Grade I listed ruin, reflecting its long and varied history.

Remains

Middleham Castle occupies a compact, rectangular footprint dominated by a large Norman keep encircled by a curtain wall dating from the 13th century. Each side of this enclosing wall extends roughly 250 feet (76 meters), creating a strong defensive perimeter that remains largely intact except for the eastern section. This part suffered damage and partial demolition during the 17th century.

The central keep, measuring about 105 feet (32 meters) from north to south and 78 feet (24 meters) from west to east, ranks among England’s largest square keeps. It rises two storeys, divided internally by a wall that separates two imposing chambers on both floors. At each corner and midway along each side stand turrets, enhancing its defensive capacity. The ground floor houses two vaulted rooms, while the upper floor contains two grand halls featuring high windows to admit light. Visitors originally entered the keep by ascending a staircase to the first floor, a typical Norman design, with a chapel built later to guard this entrance route.

A spiral staircase located in the south-east corner turret leads to the roof, from which sweeping views of the surrounding countryside and the earlier motte site can be enjoyed. The south-west turret is traditionally known as the Prince’s Tower in honor of Edward of Middleham, Richard III’s son, although no historical records confirm this association.

During the 15th century, the Neville family added significant residential buildings along the inner sides of the curtain walls. These palatial ranges were connected to the keep by first-floor bridges. The castle’s great hall was also altered by raising its ceiling, likely to incorporate either a clerestory—a high section of wall with windows to bring in additional light—or an extra chamber.

The main approach to the castle was redesigned in this era as well. The original gatehouse, which featured diagonal turrets and defensive arrow slits over the entrance arch, was replaced in the 15th century by a gatehouse tower built at the north-east corner of the curtain wall. Foundations of the original gatehouse survive facing east, pointing toward an outer ward that has since disappeared.

Constructed primarily of stone, the castle’s walls show some wear, particularly on lower sections of the keep where window frames and doorways have crumbled, floors have fallen, and battlements are partly missing. Despite this, the remaining walls retain a commanding presence. Two wells on the site highlight the castle’s capability to support its inhabitants independently. At its peak in the 14th and 15th centuries, Middleham Castle could accommodate roughly forty soldiers within its curtain walls.