Phoenice Archaeological Site: Capital of Ancient Epirus in Albania

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.5

Popularity: Very Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: bfiniq.gov.al

Country: Albania

Civilization: Byzantine, Greek, Ottoman, Roman

Remains: City

Context

The Ancient Phoenicia Archaeological Park, dating to the 3rd century BCE, is situated near the contemporary village of Finiq in southern Albania’s Vlorë County. The site occupies a gently sloping terrain that bridges inland hills with the adjacent coastal plain along the Ionian Sea. This strategic position afforded access to maritime routes and fertile hinterlands, facilitating both agricultural exploitation and trade connections during antiquity. The surrounding landscape is characterized by river valleys and low mountain ranges.

Archaeological investigations have established continuous occupation from the late Iron Age through the Hellenistic period, with material culture demonstrating significant Phoenician and Greek influences by the 3rd century BCE. Subsequent Roman presence is attested by architectural and artifact assemblages dated to the early Imperial era.

Preservation of the site varies, with exposed architectural remains and artifacts uncovered through systematic excavations initiated in the late 20th century.

History

The archaeological site near Finiq, identified as the ancient city of Phoenice, holds considerable historical significance as a political and cultural center in Epirus from the classical through late antique periods. Founded in the 5th century BCE, it served as the capital of the Chaonian tribe and later became the federal seat of the Epirote League. Its strategic location near the Ionian coast and fertile valleys underpinned its military and administrative roles amid shifting regional powers, including Illyrian incursions, Macedonian conflicts, and Roman imperial integration. The city’s trajectory reflects broader geopolitical transformations in the western Balkans and the eastern Mediterranean basin.

Archaeological and epigraphic evidence document a complex history of fortification, political prominence, and religious evolution, culminating in its decline following Ottoman conquest. Phoenice’s recorded military engagements and administrative functions position it as a key node within the networks of ancient Epirus and the Roman provinces.

Classical and Hellenistic Period (5th–3rd centuries BCE)

Established in the 5th century BCE, Phoenice emerged as the principal urban center of the Chaonians, one of Epirus’s major Greek tribes. The city occupied a naturally defensible hilltop overlooking a fertile valley, enabling control over surrounding territories. Its fortifications were constructed in three distinct phases: initial walls erected at foundation, followed by expansions in the mid-4th and 3rd centuries BCE. These massive stone walls, reaching thicknesses of up to 3.6 meters, were engineered to resist incursions from Illyrian groups and naval threats from Corcyra.

During the 4th century BCE, Phoenice expanded its urban area and erected a large theatre with an estimated capacity of 17,000 spectators. The theatre underwent two subsequent reconstructions, reflecting the city’s increasing political and cultural stature. The acropolis housed critical civic structures, including a treasury (thesaurus) safeguarding the wealth of both the city and the Epirote League, a federal alliance of regional tribes.

By the 3rd century BCE, Phoenice had become the capital of the Kaonians and the political center of Epirus. The city minted its own coinage inscribed with “ΦΟΙΝΙΚΑΙΕΩΝ,” signaling economic autonomy and active participation in regional trade networks. Following the assassination of Queen Deidamia II circa 233 BCE, Phoenice assumed the role of the Epirote League’s federal seat, marking the transition from monarchy to a federated political system.

In 231 BCE, the city was seized by Illyrian forces under Queen Teuta after the surrender of a Gaulish mercenary garrison. The Epirote League’s relief army was defeated at the Battle of Phoenice, underscoring the city’s strategic importance. The Illyrians subsequently withdrew due to internal rebellion, returning captives and the city for ransom. The killing of Roman merchants during this occupation contributed to the outbreak of the First Illyrian War.

Phoenice was the site of the 205 BCE treaty that concluded the First Macedonian War between Rome and Macedon. During the Third Macedonian War (171–168 BCE), the city aligned with Rome under the leadership of the pro-Roman faction led by Charops, further integrating it into the Hellenistic geopolitical framework.

Roman Period (167 BCE–4th century CE)

Following the Roman conquest of Epirus in 167 BCE, the region experienced widespread devastation, though Phoenice was spared due to its pro-Roman orientation. The city underwent limited Roman military occupation initially but saw urban renovations during the imperial era. Notably, a large cistern dating to the 2nd century CE was constructed, evidencing continued investment in urban infrastructure.

The settlement pattern shifted as the city expanded into the plains below the hill, consistent with Roman urban planning practices, while the acropolis remained occupied. The southern necropolis continued in use, indicating continuity in funerary customs. Administratively, Phoenice was incorporated into the Roman provincial system, likely within Epirus Nova. Although no major military engagements are recorded at the site during this period, its strategic location ensured ongoing regional relevance.

Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine Period (5th–6th centuries CE)

In late antiquity, Phoenice became an episcopal see within the early Byzantine church hierarchy. Bishops from the city participated in significant ecumenical councils, including those at Ephesus (431 CE) and Chalcedon (451 CE). Christian religious architecture flourished, with the construction of basilicas, baptisteries, and churches adorned with mosaic decoration.

Under Emperor Justinian I, the city’s urban fabric was reorganized, with the settlement relocated and fortified on the hilltop summit to address marshy conditions in the plains and enhance defensive capabilities. The fortified hilltop city persisted as a regional center into the early medieval period. The episcopal temple dedicated to the Virgin Mary, known as “Zoodochos Pigi,” was rebuilt over earlier basilicas, underscoring the city’s religious significance during this era.

Medieval Period and Decline (7th–15th centuries CE)

Throughout the medieval period, Phoenice remained inhabited as a local administrative and religious center, though its prominence diminished amid Byzantine provincial fragmentation and the advance of Ottoman power. The population comprised Byzantine Greek-speaking inhabitants and local groups, with social organization centered on ecclesiastical leadership and local governance.

Economic activities focused on subsistence agriculture, small-scale crafts, and maintenance of religious institutions. Archaeological evidence from this period is limited but indicates continued use of churches and administrative buildings. The city’s decline culminated following the Ottoman conquest in the late 15th century, leading to its abandonment.

Modern Rediscovery and Archaeological Research (20th–21st centuries)

Systematic archaeological investigation commenced in 1924 under Italian archaeologist Luigi Maria Ugolini, who uncovered key structures including the treasury, basilica, theatre, and necropolis. Although Ugolini’s work was influenced by contemporary political agendas, it established a foundational understanding of the site’s Hellenistic and Roman phases.

After a period of inactivity, Albanian and international teams resumed excavations from the 1970s onward, with intensified efforts since 2000 focusing on urban layouts and material culture. Conservation initiatives aim to protect exposed remains and integrate the site into regional heritage frameworks. Despite damage from looting incidents, ongoing research continues to elucidate Phoenice’s historical development and its role within Epirus and the ancient Mediterranean world.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Classical and Hellenistic Period (5th–3rd centuries BCE)

During its establishment and growth as the Chaonian capital, Phoenice’s population was predominantly Greek-speaking, reflecting the ethnic composition of Epirus. The social hierarchy included tribal elites, military leaders, artisans, merchants, and agricultural workers. Civic governance was exercised through assemblies representing the Molossians, Kaonians, and Thesprotians, with political decisions made in venues such as the large theatre, which also functioned as a public deliberation space.

The economy combined agriculture—cultivating cereals, olives, and grapes—with artisanal production and active trade. Excavations have revealed affluent domestic architecture, including large houses with peristyles and courtyards, indicative of wealthier inhabitants. The city minted its own coinage, evidencing economic autonomy and extensive commercial networks. Workshops producing pottery and textiles likely operated at household or small-scale levels. The city’s proximity to the Ionian coast facilitated maritime trade, while inland exchanges connected it to regional markets.

Dietary remains suggest a Mediterranean pattern centered on cereals, olives, wine, and fish. Clothing likely consisted of woolen tunics and cloaks, with sandals as common footwear. Domestic interiors featured mosaic floors and painted walls, with homes organized around central courtyards serving multiple functions. The necropolis on the southern slopes contains richly furnished tombs, reflecting social stratification and funerary customs.

Religious life focused on the cult of Athena Polias, with temples and altars situated on the acropolis. Civic festivals and rituals likely accompanied political assemblies, reinforcing communal identity. The city’s role as the Epirote League’s federal seat after 233 BCE elevated its political importance, hosting diplomatic events such as the 205 BCE treaty ending the First Macedonian War. Military conflicts, including the Illyrian siege in 231 BCE, underscored Phoenice’s strategic significance.

Roman Period (167 BCE–4th century CE)

Following Roman conquest, Phoenice’s population remained largely Greek-speaking, with a blend of local Epirote and Roman settlers. The social structure included Roman officials, local elites, artisans, and farmers. The city’s pro-Roman stance spared it from widespread destruction, allowing urban life to continue and adapt to Roman administrative models.

Economic activities expanded with Roman infrastructural investments, notably the construction of a large cistern in the 2nd century CE, indicating organized water management. Agriculture remained central, supplemented by trade facilitated through the city’s expansion into the plains. Workshops and markets likely supplied goods such as pottery and textiles. Coin finds confirm ongoing commercial exchanges.

Diet and clothing maintained Mediterranean characteristics, with Roman influences evident in tunics and cloaks worn alongside traditional Greek garments. Domestic architecture evolved to include Roman-style houses with courtyards and mosaic decoration, maintaining continuity with earlier designs. The southern necropolis’s continued use reflects sustained funerary traditions.

Religious life incorporated Roman deities alongside local cults, though explicit evidence is limited. Civic administration aligned with the Roman provincial system, possibly governed by local magistrates under provincial oversight. Phoenice functioned as a municipium within Epirus Nova, retaining regional importance as an administrative and defensive center without recorded major military conflicts.

Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine Period (5th–6th centuries CE)

In late antiquity, Phoenice’s population increasingly embraced Christianity, becoming an episcopal see with bishops attending major ecumenical councils. The social fabric included clergy, local administrators, and laypeople organized around the church’s growing influence. Family and social structures likely reflected Christian norms, with ecclesiastical leaders playing prominent civic roles.

Economic life shifted toward sustaining religious institutions and local needs amid broader regional transformations. Archaeological remains of basilicas, baptisteries, and mosaic-decorated churches attest to active religious communities. The urban center was reorganized under Emperor Justinian I’s directive, relocating to the fortified hilltop to avoid marshy plains, reflecting adaptive urban planning.

Diet and clothing maintained Mediterranean continuity, though Christian modesty may have influenced attire and social customs. Domestic spaces incorporated religious iconography, and educational activities likely included catechesis and Christian instruction, though direct evidence is scarce. The episcopal temple dedicated to the Virgin Mary became a focal point of worship and community identity.

Phoenice’s role evolved into a religious and administrative hub within the Byzantine provincial framework, balancing ecclesiastical authority with local governance. The fortified hilltop city served as a refuge and symbol of continuity during a period of political fragmentation and external pressures.

Medieval Period and Decline (7th–15th centuries CE)

During the medieval era, Phoenice’s population comprised Byzantine Greek-speaking inhabitants and local groups, with social organization centered on ecclesiastical leadership and local administration. The city’s prominence declined amid provincial fragmentation and shifting trade routes.

Economic activities focused on subsistence agriculture, small-scale crafts, and maintenance of religious institutions. Archaeological evidence from this period is limited but indicates continued use of churches and administrative buildings. Clothing and domestic life likely reflected Byzantine rural and urban traditions, with modest homes and community-oriented lifestyles.

Remains

Architectural Features

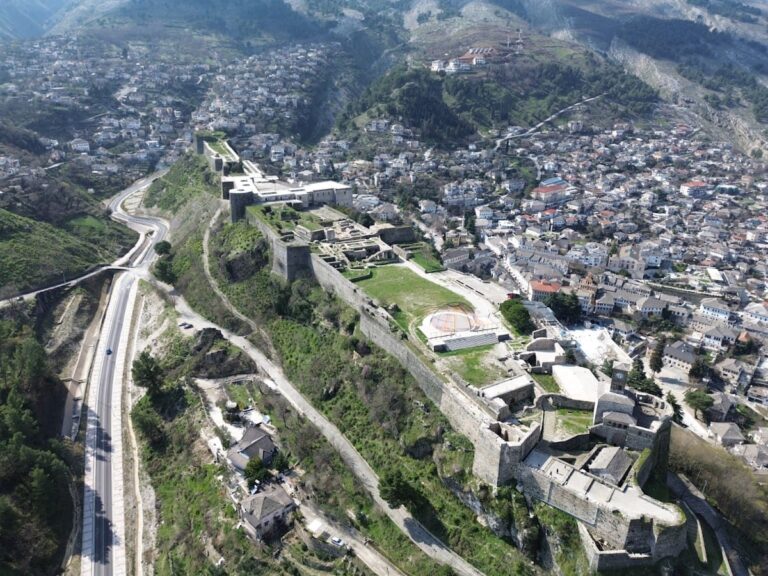

Phoenice’s urban fabric is defined by substantial fortification walls constructed in three principal phases: the initial 5th-century BCE foundation walls, mid-4th-century BCE expansions, and further enhancements in the 3rd century BCE coinciding with the city’s growth and coin minting activities. These walls, composed of large stone blocks up to 3.6 meters thick, were engineered to withstand Illyrian and Corcyraean assaults. In the 6th century CE, Emperor Justinian I commissioned additional fortifications on an adjacent hill and ordered the city’s relocation to the hilltop to mitigate marshy conditions in the lower town.

The city’s layout evolved from a hilltop acropolis to include terraced southern slopes and, during the Roman period, expansion into the plains below. Construction primarily employed local stone masonry. The acropolis remained the civic and religious nucleus throughout occupation, containing key public and sacred buildings. The urban area comprises residential, religious, and public structures, reflecting a multifunctional settlement.

Key Buildings and Structures

Theatre

The theatre, originally constructed in the early 4th century BCE using local hill stone, underwent two major reconstructions: one in the 3rd century BCE during Phoenice’s ascendancy as the capital of Chaonia and Epirus, and another in the 2nd century CE under Roman rule. The orchestra measures approximately 19.80 meters in diameter, marginally larger than the theatre at Dodona. The semicircular seating (cavea) extends about 129.5 meters from center to top. Large pedestals with footprints discovered on the stage likely supported statues of deities or emperors. The theatre is centrally located on the hill, oriented toward the Monastery of the Forty Saints.

City Walls and Fortifications

The city’s defensive walls were constructed in three phases: initial 5th-century BCE foundation, mid-4th-century BCE expansion, and 3rd-century BCE reinforcement concurrent with urban growth and coin minting. The walls feature massive stone blocks designed for military defense. In the 6th century CE, Justinian I added fortifications on a nearby hill and ordered the settlement’s relocation to the hilltop, enhancing defense and addressing environmental challenges.

Acropolis and Agora

The acropolis, situated at the hill’s summit, served as the city’s central complex, housing the most substantial and well-preserved monuments, including the Thesaurus and a large basilica. It functioned as a social and administrative center and remained occupied through the city’s decline. While the agora was integrated within this elevated zone, specific market structures have not been distinctly identified.

Thesaurus (Temple)

Constructed in the mid-3rd century BCE, the Thesaurus is a temple-like edifice on the acropolis that functioned as a treasury for the city and the Epirote League. Excavated in the 1920s, its remains include foundational walls and architectural fragments consistent with temple design.

Large Basilica near the Thesaurus

Adjacent to the Thesaurus are remains of a large basilica, likely dating to the early Christian period. Foundations and partial walls survive, indicating a sizable religious structure. Early Christian artifacts found nearby support its use during the 5th and 6th centuries CE.

Early Christian and Paleochristian Churches

Several early Christian religious buildings have been identified, including a baptistery and churches dating to the 5th and 6th centuries CE. In the area known as “Palea Avli,” ruins of paleochristian temples with mosaic floors survive. The episcopal temple dedicated to the Virgin Mary, “Zoodochos Pigi,” was initially constructed over an older basilica and later rebuilt on the mountain slopes within the town center.

House of the Two Peristyles

This residential building, dating to the 3rd century BCE, covers approximately 700 square meters. It features a nearly square plan centered on a large rectangular courtyard surrounded by a colonnaded walkway (peristyle). Several smaller rooms open onto the courtyard. Located on the southern slopes, the house forms part of the Hellenistic urban fabric.

Roman Cisterns

Two large cisterns excavated on the acropolis date to the 2nd century CE. These masonry structures were integral to the city’s water management system, comprising vaulted chambers and channels designed to collect and store water.

Necropolis

The necropolis lies at the base of the southern hill slope and was in use during the Hellenistic and Roman periods. Excavations uncovered numerous tombs containing ceramics, coins inscribed with “ΦΟΙΝΙΚΑΙΕΩΝ,” and other grave goods. Approximately 358 coin types were recorded, with 314 from the Hellenistic era. One tomb dating to the late 4th century BCE contained rich grave offerings. The necropolis includes both chamber tombs and pit graves.

Other Remains

Surface surveys and excavations have revealed architectural fragments and traces of workshops and possible storage buildings, though their precise functions remain undetermined. Remains of a baptistery and other early Byzantine religious structures have been identified. The urban area expanded notably in the 3rd century BCE toward the center and western sides of the hill, with terraced construction on the southern slopes following Hellenistic urban planning principles.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations have yielded artifacts spanning from the late Iron Age through late antiquity. Pottery assemblages include locally produced and imported amphorae and tableware from the Hellenistic and Roman periods. Numerous coins bearing the inscription “ΦΟΙΝΙΚΑΙΕΩΝ” represent a chronological range from the 4th to 1st centuries BCE, indicating active economic exchange and minting activity.

Inscriptions recovered include dedicatory texts linked to public buildings and religious dedications, though no extensive epigraphic corpus has been published. Domestic artifacts such as lamps, cooking vessels, and tools have been found primarily in residential contexts like the House of the Two Peristyles. Religious artifacts include statuettes and altars associated with early Christian worship, particularly in basilicas and baptisteries.

Preservation and Current Status

The site’s preservation varies. The theatre’s stone seating and stage area survive partially, with some structural elements collapsed or eroded. City walls remain visible in sections but are fragmentary. The acropolis retains substantial architectural remains, including the Thesaurus and basilica foundations, though above-ground walls are incomplete.

Roman cisterns and the House of the Two Peristyles are preserved mainly as foundations and partial walls. Necropolis tombs are variably preserved, with some damaged or looted, notably a Hellenistic tomb affected by looting in 2012. Early Christian churches and baptisteries survive as ruins with mosaic fragments and wall bases.

Conservation efforts have stabilized several structures, but restoration remains limited. Vegetation and erosion pose ongoing risks. Archaeological work continues under Albanian and international collaboration, with detailed stratigraphic documentation and mapping guiding preservation strategies.

Unexcavated Areas

Several parts of the ancient city remain unexcavated or only partially explored. Surface traces on the western and central hill slopes suggest buried structures. The plains below the hill, where the city expanded during the Roman period, have not been fully investigated. Geophysical surveys have been limited, and some zones are inaccessible due to modern land use or military restrictions.

Future excavations are planned but constrained by conservation policies and site protection measures. The full extent of residential, economic, and possible industrial districts remains to be clarified through further archaeological research.