Neapolis Archaeological Park, Syracuse: A Historic Greek and Roman Site in Sicily

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.3

Popularity: Very High

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: parchiarcheologici.regione.sicilia.it

Country: Italy

Civilization: Byzantine, Greek, Roman

Remains: City, Civic, Entertainment, Religious, Sanitation

Context

The Neapolis Archaeological Park is situated within the contemporary city of Syracuse on Sicily’s eastern coastline, Italy. It occupies a prominent rocky promontory overlooking the Ionian Sea, characterized by a natural amphitheater-like formation. The site’s topography includes an elevated plateau known as Temenite hill, flanked by steep cliffs, which historically influenced its defensive and ceremonial functions. Its proximity to the ancient harbor facilitated maritime connectivity across the central Mediterranean, shaping settlement patterns and economic activities in the area.

Archaeological evidence demonstrates continuous occupation beginning in the 5th century BCE during the Greek colonial establishment of Syracuse. The site evolved through the Roman Imperial period, adapting to changing urban and military requirements. Although occupation declined in late antiquity, reflecting wider regional transformations, the archaeological record preserves a complex stratigraphy of cultural phases. The park’s rocky terrain and limited modern construction have contributed to the preservation of its monuments. Italian heritage authorities have undertaken conservation and management efforts to protect the site and integrate it within Syracuse’s cultural environment.

History

The Neapolis Archaeological Park embodies a multi-layered historical narrative spanning from its origins as a Greek colonial district to its development under Roman rule and subsequent Christianization in late antiquity. Its strategic location on Temenite hill, overlooking the Ionian Sea, provided both military advantages and access to vital water resources, supporting urban growth and quarrying activities. The site played a role in significant historical episodes, including the Athenian siege during the Peloponnesian War, and later adapted to Roman administrative and funerary customs. Although its prominence diminished in late antiquity, the area remained a locus of religious transformation. Modern archaeological investigations have elucidated these phases, situating Neapolis within the broader historical context of Sicily’s evolving political and cultural landscape.

Greek Colonial and Siceliote Period (5th–3rd centuries BCE)

During the 5th century BCE, the Neapolis district emerged as part of the Greek polis of Syracuse, founded by settlers from Corinth and Tenea. This period, known as the Siceliote phase, saw the consolidation of Greek political and cultural institutions in eastern Sicily. The elevated Temenite hill, referenced by Thucydides in his account of the Athenian siege of Syracuse (415–413 BCE), served as a strategic military encampment for Athenian forces. The natural amphitheater shape of the promontory and its proximity to the harbor made it a defensible and ceremonial space within the city’s urban fabric.

Archaeological remains from this era include the Greek Theatre, located near the summit of Temenite hill, which functioned as a venue for dramatic performances and civic assemblies. The area was supported by sophisticated hydraulic infrastructure, including the Ninfeo and Galermi aqueducts, which supplied water to springs and the Nymphaeum cave. Quarrying was a significant economic activity, with the Latomia del Paradiso exploited for large limestone blocks used in monumental construction; this quarry reaches depths of 45 meters and contains notable cavities such as the Orecchio di Dionisio. Funerary monuments from the Siceliote period survive, though they are less prominent than those from later Roman phases.

Roman Imperial Period (1st century BCE – 3rd century CE)

Following the Roman conquest of Sicily in the 3rd century BCE, Syracuse was incorporated into the Roman provincial system as part of Sicilia. During the Imperial period, the Neapolis district remained a vital urban quarter within the city. Archaeological evidence attests to the construction of Roman public buildings, including an amphitheater and a piscina (Roman pool), reflecting the adaptation of the area to Roman recreational and urban needs. The presence of the Triumphal Arch of Augustus within the park signifies the city’s integration into the imperial cult and Roman political structures.

The Ara of Hiero II, a large altar dating to the Hellenistic period, continued to hold religious significance during Roman times, indicating continuity of cult practices. The Grotticelle necropolis contains numerous Roman chamber tombs, including the elaborately decorated so-called “Tomb of Archimedes,” which dates to the 1st century CE. This tomb features Doric semi-columns and relief carvings on the rock face and contained funerary urns consistent with Roman cremation customs, distinguishing it from earlier Siceliote inhumation practices. The Roman Columbarium of Neapolis further confirms the use of urn burial in this district. Infrastructure improvements during this period included roads and urban walls near the necropolis, as well as a possible sacred building constructed atop earlier foundations, reflecting the integration of Neapolis into the Roman urban landscape.

Late Antiquity and Christianization

In late antiquity, Syracuse underwent significant religious and administrative changes as Christianity spread throughout Sicily. The Church of San Nicolò ai Cordari, located within the park, exemplifies the Christianization of the area, likely dating from the late Roman or early medieval period. This development marked a transition from earlier pagan religious practices centered on altars such as the Ara of Hiero II. The archaeological record indicates a decline in occupation during this period, consistent with broader regional trends of political instability and economic contraction.

While specific causes for the reduction in activity at Neapolis remain insufficiently documented, the site’s diminished prominence aligns with the general pattern of urban contraction in late antiquity. No substantial evidence of Byzantine or later medieval occupation has been identified within the park, though the Christian presence suggests continued, albeit limited, use of the area during the early medieval period.

Modern Rediscovery and Excavation (19th–20th centuries)

Systematic archaeological exploration of Neapolis commenced in the 19th century under Domenico Lo Faso, Duke of Serradifalco, whose pioneering work was published in 1840. Subsequent investigations by Paolo Orsi and Luigi Bernabò Brea in the 20th century expanded understanding of the site’s complex stratigraphy and historical phases. Between 1952 and 1955, Bernabò Brea directed the establishment of the archaeological park, designed by V. Cabianca, to safeguard the monuments amid rapid urban expansion in Syracuse.

The park’s creation aimed to preserve the archaeological heritage while integrating it into the city’s cultural framework. Despite its protected status, the site has faced ongoing challenges related to funding, management, and maintenance, which have affected conservation efforts and public accessibility. Nevertheless, Italian heritage authorities continue to implement measures to protect the park’s remains and promote its historical significance.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Greek Colonial and Siceliote Period (5th–3rd centuries BCE)

During the Greek colonial era, the Neapolis district was inhabited predominantly by settlers from Corinth and Tenea, embedded within the Siceliote Greek cultural sphere. The population was organized according to the polis model, with male citizens participating in civic assemblies and religious festivals. Social stratification included landowning elites, artisans, laborers, and resident foreigners (metics), alongside enslaved individuals. Family structures were patriarchal, with women managing domestic affairs.

Economic activities centered on quarrying limestone from the Latomia del Paradiso, agriculture producing olives, grains, and fruits in surrounding areas, and maritime trade facilitated by the nearby harbor. Hydraulic infrastructure such as the Ninfeo and Galermi aqueducts supported domestic water supply and public amenities. Artisans operated workshops producing pottery, textiles, and metal goods. Public spaces like the Greek Theatre hosted dramatic performances and civic events, reflecting an active cultural life. Diet consisted mainly of cereals, olives, wine, fish, and local fruits, consistent with Mediterranean staples. Clothing included linen and wool tunics, cloaks, and sandals, inferred from regional parallels and iconography.

Roman Imperial Period (1st century BCE – 3rd century CE)

Under Roman rule, Neapolis became an integrated urban quarter within the municipium of Syracuse. The population diversified to include Roman settlers, local Sicilians, freedmen, and slaves. Social hierarchy featured senatorial and equestrian elites, municipal magistrates such as duumviri, artisans, merchants, and laborers. Extended households were common among wealthier classes, maintaining patriarchal family structures.

Economic life expanded to encompass public entertainment and leisure, evidenced by the Roman Amphitheatre and piscina, alongside continued quarrying and artisanal production. The Triumphal Arch of Augustus and monumental tombs like the “Tomb of Archimedes” reflect adoption of Roman funerary and religious customs, including cremation and imperial cult worship. Workshops producing ceramics, textiles, and metal goods likely operated at a neighborhood scale. Diet incorporated bread, olives, fish, wine, and fruits, supplemented by imported delicacies from across the empire. Clothing styles adapted Roman fashions, including tunics, togas for citizens, and stolae for women. Domestic interiors featured mosaic floors, painted walls, and furniture such as couches and storage chests. Houses typically included atria, peristyles, kitchens, and storage rooms, indicating architectural sophistication. Markets supplied local and imported goods, with transport networks connecting Neapolis to the city center and wider province. Religious life combined traditional Hellenistic cults, the imperial cult, and emerging Christian communities.

Late Antiquity and Christianization

In late antiquity, Neapolis experienced demographic decline and functional transformation amid regional instability. The population decreased, and Christian religious practices supplanted earlier pagan cults. The Church of San Nicolò ai Cordari within the park exemplifies this transition, likely serving a modest Christian community engaged in liturgical worship and instruction. Economic activities contracted, focusing on subsistence and local services rather than large-scale production or trade. The decline in monumental construction and urban maintenance reflects reduced municipal resources and population.

Domestic life adapted to simpler conditions, with fewer archaeological indicators of elaborate decoration or luxury goods. Clothing and diet likely remained consistent with Mediterranean traditions but on a reduced scale. Markets and transport networks diminished, with local footpaths and limited cart traffic replacing extensive Roman infrastructure. Social organization shifted toward ecclesiastical leadership, with bishops and clergy assuming civic roles previously held by magistrates. Educational and cultural life centered on Christian instruction and liturgical readings rather than classical civic activities. Neapolis contracted from a vibrant urban quarter to a smaller religious precinct within a shrinking city, mirroring broader patterns of urban decline and Christianization in Sicily during late antiquity.

Remains

Architectural Features

The Neapolis Archaeological Park preserves a diverse array of structures spanning from the 5th century BCE through the 3rd century CE. Situated on Temenite hill, a natural promontory with an elevated plateau and steep cliffs, the site’s topography influenced the placement and design of buildings. The architectural remains include civic, religious, funerary, and infrastructural elements that document Syracuse’s evolution from a Greek polis to a Roman city.

Construction techniques vary from large ashlar limestone blocks quarried locally, particularly from the Latomia del Paradiso, to Roman concrete (opus caementicium) and brickwork in later structures. The park’s layout reflects a division between the southern zone, containing early Greek monuments, and the northern zone, dominated by deep latomies (stone quarries). Defensive walls, public buildings, and hydraulic installations were strategically positioned in relation to the terrain and the ancient harbor. The site exhibits phases of urban growth and contraction, with architectural modifications corresponding to political and religious changes.

Key Buildings and Structures

Greek Theatre of Syracuse

Dating to the 5th century BCE Siceliote period, the Greek Theatre is located near the highest point of Temenite hill. The theatre features a semicircular seating area (cavea) hewn into the natural slope, designed for dramatic performances and civic gatherings. The stone seating remains partially preserved, allowing assessment of the theatre’s original scale and orientation. Its elevated position exploits the natural amphitheater shape of the promontory. While decorative elements have not survived, the structure conforms to typical Greek theatre design of the period.

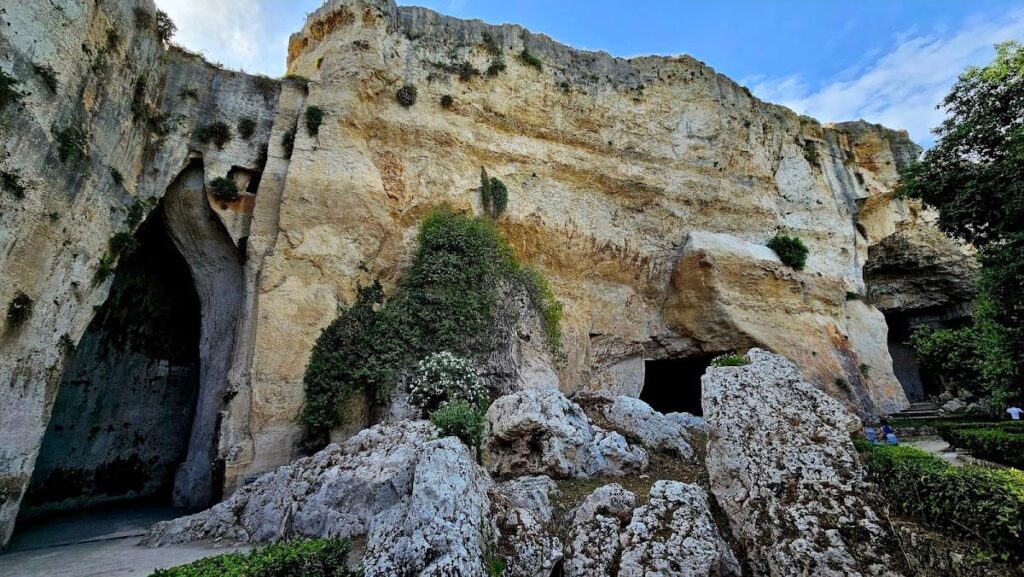

Latomia del Paradiso

The Latomia del Paradiso is the largest and westernmost stone quarry within the park, reaching depths of up to 45 meters. It was actively exploited from the Greek colonial period for extracting large limestone blocks used in Syracuse’s monumental architecture. The quarry contains several large cavities, including the Orecchio di Dionisio (Ear of Dionysius), Grotta dei Cordari, and Grotta del Salnitro, carved directly into the rock face. These cavities exhibit evidence of ancient quarrying techniques. Portions of the latomia are accessible to visitors, while others remain closed for preservation and safety.

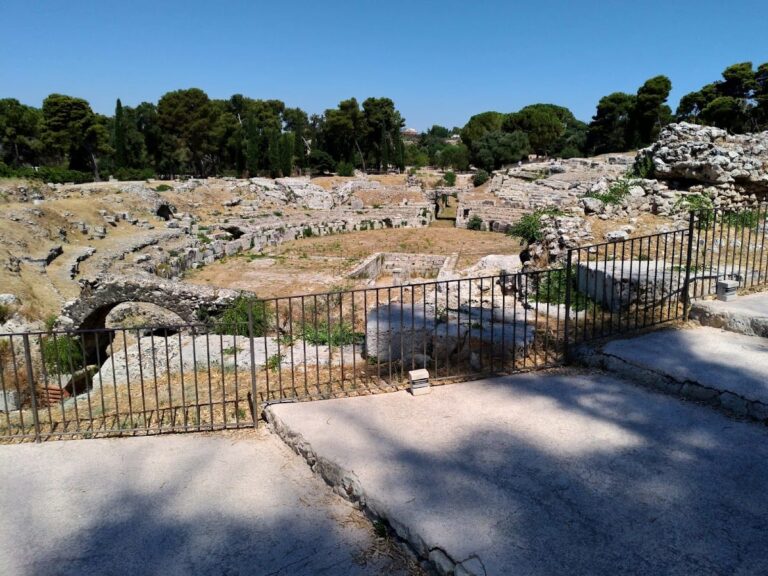

Roman Amphitheatre of Syracuse

Constructed in the 1st century CE, the Roman Amphitheatre is situated within the park area historically known as “the pit of pomegranates,” named for the abundant pomegranate trees in the vicinity. The remains include sections of the arena and seating structures, built using Roman masonry techniques adapted to the natural terrain. Although partially preserved, detailed architectural features such as vomitoria (entrance passages) or substructures have not been extensively documented.

Ara of Hiero II

Located near the western edge of the Latomia del Paradiso, the Ara of Hiero II is a large altar originally dating to the Hellenistic period (3rd century BCE). The altar continued in use during the Roman Imperial period, indicating continuity of religious practice. Constructed of stone, it comprises a broad base and altar platform, though much of the superstructure is fragmentary. Its proximity to the quarry suggests a religious function connected to the surrounding landscape. No detailed measurements or decorative elements have survived.

Necropolis Grotticelle

The Grotticelle necropolis lies near the Latomia di Santa Venera at the southern end of the park, adjacent to densely urbanized areas. Excavations uncovered a stretch of ancient road and wall structures dating to pre-Greek or early Greek periods. The necropolis contains numerous tombs from Sicilian, Greek, and Roman phases. Sicilian and Greek tombs are primarily pit graves, often shallow and less visible. Roman tombs are mainly chamber tombs, architecturally prominent and visible above ground.

The most notable funerary monument is the so-called “Tomb of Archimedes,” constructed in the 1st century CE. This chamber tomb features Doric semi-columns in relief and a sculpted pediment carved directly into the rock face. Inside, funerary urns consistent with Roman cremation practices were found. Despite local tradition, this tomb postdates Archimedes by several centuries. The necropolis also includes a Roman columbarium used for urn burial.

Grotta del Ninfeo

The Grotta del Ninfeo is a natural cave on the terrace of Temenite hill where water from the Ninfeo aqueduct emerges. This cave is part of a hydraulic system that included the Galermi aqueduct, once connected via a now-lost bridge and waterfall. The cave’s stone walls bear traces of water management and possibly ritual use. It is situated near the Greek Theatre and the spring named after Temenite hill.

Church of San Nicolò ai Cordari

Within the park stands the Church of San Nicolò ai Cordari, dating from the late Roman or early medieval period. This structure represents the Christianization of the area during late antiquity. Although detailed architectural descriptions are limited, the church’s remains include foundational walls and partial masonry, indicating a modest-sized religious building. It is located near the necropolis and other late antique structures.

Roman Pool (Piscina Romana)

The Roman Pool, constructed in the 1st century CE, is a water basin or pool located within the park. Its masonry walls and water containment features are partially preserved. The pool likely served recreational or utilitarian functions within the Roman urban quarter. No detailed architectural plans or decorative elements have been documented.

Arch of Augustus

The Arch of Augustus is a Roman triumphal arch situated within the park, dating to the 1st century CE. The surviving remains include portions of the arch’s masonry and foundations. The arch marked Syracuse’s incorporation into the imperial cult and Roman political order. No inscriptions or sculptural decorations have been preserved in situ.

Other Remains

The park contains numerous additional archaeological features, including sarcophagi, Hellenistic houses, and funerary monuments scattered throughout the necropolis and urban areas. Remains of pre-Greek or Greek walls and road surfaces have been documented near the necropolis. Possible foundations of a sacred building, constructed over earlier archaic structures, were uncovered adjacent to the necropolis. Several smaller latomies, such as the Latomia dell’Intagliatella and Latomia di Santa Venera, are present but less extensively excavated or accessible.

A modern bronze statue of Prometheus by Biagio Tommaso Poidimani, measuring three meters tall, is located near the park’s entrance outside the archaeological perimeter. This contemporary work references Syracuse’s Greek mythological heritage but is not part of the ancient remains.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations at Neapolis have yielded a variety of artifacts spanning Greek, Hellenistic, Roman, and late antique periods. Pottery finds include locally produced and imported amphorae and tableware, recovered primarily from domestic and funerary contexts. Numerous inscriptions have been documented, including dedicatory formulas linked to public buildings and tombs. Coins from various Roman emperors indicate economic activity and circulation within the city. Tools related to quarrying and construction have been uncovered in the latomies. Domestic objects such as oil lamps and cooking vessels appear in residential areas. Religious artifacts include fragments of altars and ritual vessels associated with the Ara of Hiero II and other sanctuaries.

Funerary urns and sarcophagi from the Roman necropolis provide evidence of cremation and burial customs. Architectural fragments, including relief decorations from the Tomb of Archimedes, have been recovered and studied. These finds collectively illustrate the material culture and urban development of Neapolis across several centuries.

Preservation and Current Status

The Neapolis Archaeological Park preserves many structures in varying states of conservation. The Greek Theatre and Latomia del Paradiso retain substantial visible remains, though some quarry sections are closed for safety and preservation. The Roman Amphitheatre and necropolis tombs survive partially, with some chamber tombs accessible but others fragmentary. Restoration efforts have stabilized several monuments, including the Tomb of Archimedes, where relief decorations have been conserved.

The park’s enclosure, designed in the 1950s, has prevented urban encroachment, aiding preservation of both monuments and local vegetation. However, maintenance challenges persist, including limited funding and restricted public access to some areas. Environmental factors such as sea winds and vegetation growth affect exposed stone surfaces. Conservation programs by Italian heritage authorities continue to monitor and protect the site, balancing preservation with archaeological research.

Unexcavated Areas

Several parts of the ancient Neapolis district within the park remain unexcavated or only partially studied. Smaller latomies like the Latomia dell’Intagliatella and Latomia di Santa Venera have surface traces but lack comprehensive excavation. The area around the Mulini di Galerme on Temenite hill is documented but not fully explored archaeologically. Subsurface remains beneath the modern urban fabric adjacent to the park, especially near the necropolis and Via dei Sepolcri, are largely inaccessible. Geophysical surveys and historic maps suggest additional buried structures, but excavation is limited by conservation policies and urban development. Future archaeological work is planned cautiously to preserve the site’s integrity.