Lixus: An Ancient Maritime and Commercial Center in Northern Morocco

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.4

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.facebook.com

Country: Morocco

Civilization: Early Islamic, Phoenician, Roman

Remains: City

Context

The archaeological site of Lixus is situated on a rocky promontory overlooking the estuary of the Loukkos River near the modern city of Larache in northern Morocco. The site occupies a series of terraces descending toward the Atlantic coastal plain, commanding views over tidal channels, marshlands, and the river mouth. This strategic location provided natural advantages for maritime anchorage, access to freshwater, and exploitation of salt marshes, which supported fishing and salt production activities. The surrounding landscape includes fertile plains and navigable waterways that facilitated inland connections and trade routes.

Archaeological investigations have revealed a long sequence of occupation at Lixus, beginning with indigenous Late Bronze Age communities and continuing through Phoenician and Punic colonization, Mauretanian rule, Roman provincial administration, and later Islamic settlement. Material culture and stratigraphic evidence demonstrate the site’s adaptation to shifting political and economic contexts, with phases of urban expansion and contraction. While many structures survive as exposed ruins, significant portions remain buried, offering ongoing opportunities for research. The site’s location at the interface of riverine and Atlantic environments shaped its historical development as a maritime and commercial center within the broader northwest African region.

Interest in Lixus has grown since early twentieth-century surveys and excavations, with Moroccan cultural heritage authorities leading recent efforts to document, conserve, and interpret the site. Excavations have uncovered architectural remains, mosaics, inscriptions, and artifact assemblages that illuminate the city’s long-term occupation and cultural interactions.

History

Lixus’s historical trajectory spans from indigenous Late Bronze Age settlement through Phoenician foundation, Punic and Mauretanian phases, Roman imperial integration, and medieval Islamic occupation. Archaeological and epigraphic evidence attest to its evolving civic status, economic specialization, and religious transformations.

Pre-Phoenician and Phoenician Period (c. 1300–300 BCE)

Prior to Phoenician settlement, the site was occupied by indigenous communities during the Late Bronze Age (circa 1300–1150 BCE), as indicated by locally produced ceramics, megalithic architectural elements, and bronze weaponry. These early inhabitants engaged in subsistence activities and local trade within the Atlantic coastal environment. In the 8th or 7th century BCE, Phoenician colonists established Lixus, making it one of the earliest Phoenician settlements on Morocco’s Atlantic coast, predating even Carthage. Archaeological remains in the “Temples quarter” include stone buildings constructed with quadrangular and megalithic blocks, alongside characteristic Phoenician ceramics such as red slip pottery and Cruz de Negro jugs.

Lixus formed part of a network of Phoenician maritime outposts along the Atlantic, including Chellah and Mogador, facilitating trade and fishing activities. Its location on an 80-meter-high hill overlooking the Loukkos estuary and the ocean provided natural advantages for anchorage and surveillance. Surrounding marshy plains supported salt production, an important resource for preserving fish and trade goods. The site’s early urban layout and material culture reflect integration of Phoenician settlers with local Berber populations, establishing a cultural synthesis that shaped its initial development.

Punic and Mauretanian Period (4th–1st century BCE)

Following the Second Punic War, Lixus came under the influence of the Mauretanian kingdom, a client state allied with Rome. During this period, the city’s economy increasingly specialized in fish products, particularly salted fish and fermented fish sauces, as evidenced by numerous amphora fragments used for packaging and export. Urban modifications included refurbishment of buildings with voussoir arches and the installation of cisterns, reflecting advances in water management and urban planning. The “Temples quarter” continued to be used.

Lixus maintained a degree of autonomy within the Punic cultural sphere, preserving local religious traditions distinct from Carthaginian deities such as Ba’al Hammon and Tanit. The city’s protective deity, possibly Milqart or Chosour, appears on local coinage as a youthful figure wearing a conical tiara and occasionally holding a double axe. The population was ethnically diverse, comprising Phoenician, Cananean, Aegean settlers, and indigenous Berber groups. Lixus functioned as a semi-autonomous city within the Mauretanian kingdom.

Mauretanian Kingdom and Early Roman Influence (1st century BCE – AD 40)

Under the reigns of King Juba II (25 BCE–23 CE) and his son Ptolemy, Lixus underwent urban expansion and architectural refinement. A large palatial complex, covering approximately 7,000 square meters, was constructed on the southern slope of the hill, surpassing the size of the Palace of Gordianus at Volubilis. The palace featured apses, semicircular porticoes, large windows, and triple doors, integrating enclosed spaces with gardens and terraces overlooking the river and coast. Building F within the complex is interpreted as the principal triclinium (dining hall), used for official functions. A marble throne discovered on site supports the identification of this complex as a royal residence.

The city’s economy diversified to include viticulture alongside fishing and salt production, with the port facilitating Atlantic trade in wine, fish products, and salt. Residential neighborhoods developed with houses equipped with cisterns and temples, some of which remained in use after Roman annexation. The assassination of King Ptolemy by Emperor Caligula around AD 40 ended Mauretanian independence, leading to direct Roman administration of the region.

Roman Imperial Period (AD 40 – 5th century)

Following the annexation of Mauretania, Lixus was incorporated into the Roman province of Mauretania Tingitana and elevated to the status of a Roman colony under Emperor Claudius around AD 50. The city expanded to cover over 60 hectares, becoming the largest urban center in the province between the mid-1st and mid-2nd centuries. Roman urban infrastructure included an amphitheatre, unique in Morocco, designed for both gladiatorial contests and theatrical performances, a forum, richly decorated public baths, and a complex of temples and sanctuaries.

The “Temples quarter” underwent substantial architectural transformation, featuring a Corinthian atrium, bath complexes likely dating to the Flavian period, and large halls with peristyles and Ionic columns. The economy remained centered on fishing and the production of garum, a fermented fish sauce made from tuna viscera. Industrial complexes comprising up to ten factories and 150 basins could produce up to one million liters of garum per fishing season, utilizing fresh water from the Loukkos River for cleaning and brining. Residential areas contained spacious Roman houses with private baths and elaborate mosaics depicting mythological scenes such as Mars and Rhea Silvia, Helios, Eros and Psyche, and Bacchic processions, reflecting the wealth of inhabitants linked to the garum industry and agricultural estates.

Christianity became established by the 3rd century, as evidenced by the remains of a Paleochristian church overlooking the site. From the late 3rd century onward, Lixus experienced decline amid regional instability and military anarchy. The urban area contracted, and new fortifications were constructed as the city assumed a frontier role following Diocletian’s administrative reforms in 286 AD.

Late Antiquity and Early Islamic Period (4th – 15th century)

After the Roman withdrawal and Vandal incursions in the early 5th century, Lixus underwent gradual decline but remained inhabited. Christian communities persisted into late antiquity. During the medieval Islamic period, the site, known as Tochoummis or Tchoummich, hosted a mosque and hammam dating to the Almohad or Marinid dynasties (12th–14th centuries). The urban area contracted to approximately 14 hectares, with the “Temples quarter” marking the northern boundary of the settlement.

Archaeological remains from this period include a rectangular religious building, thermal baths, a large fountain, and residential structures, indicating continuity and adaptation of the urban fabric to Islamic cultural and architectural norms. By the 14th century, Lixus was largely abandoned in favor of the fortified city of Larache across the Loukkos River. Since the late 20th century, Moroccan heritage authorities have undertaken restoration and archaeological research to preserve and interpret the site’s history.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Phoenician Foundation and Expansion (8th–7th century BC)

During its initial Phoenician phase, Lixus was a coastal trading settlement where Phoenician colonists integrated with local Berber populations. The community comprised maritime traders, artisans, and salt producers, with social organization centered on managing trade networks and religious activities focused in the “Temples quarter.” Economic life revolved around fishing, salt extraction from nearby marshes, and ceramic production, including red slip pottery and Cruz de Negro jugs used for storage and transport.

Punic-Mauritanian Period (4th–1st century BC)

Under Punic-Mauritanian influence, Lixus’s population became ethnically diverse, blending Phoenician, Cananean, Aegean settlers, and indigenous Berbers. Social stratification increased, with local elites overseeing fish-salting industries and religious cults dedicated to a protective deity distinct from Carthaginian gods. Extended kin groups likely managed workshops and agricultural estates. The economy specialized in fish products, notably salted fish and fish sauces, produced at an industrial scale as indicated by amphora fragments and large cisterns.

Urban planning incorporated voussoir arches and improved water management systems. Domestic spaces evolved to include houses with cisterns and open courtyards, though interior decoration remains sparsely documented. Markets probably offered imported luxury goods alongside local produce, with transport combining riverine navigation and overland routes. Religious life maintained Punic traditions, with temples hosting rituals and festivals honoring local deities.

Mauretanian Kingdom and Early Roman Influence (1st century BC – AD 40)

During the reigns of Juba II and Ptolemy, Lixus’s population included royal administrators, artisans, fishermen, and agricultural workers, reflecting a cosmopolitan society influenced by Hellenistic and Roman cultures.

Economic activities diversified to include viticulture alongside fishing and salt production. The port facilitated Atlantic trade in wine, fish products, and salt. Residential neighborhoods contained houses with cisterns and temples supporting religious observance. Religious practices blended Punic and Hellenistic elements, with temples dedicated to traditional and syncretic deities. Lixus functioned as a royal capital and regional economic center until Roman annexation.

Roman Imperial Period (AD 40 – 5th century)

Following Roman annexation, Lixus’s population expanded to include Roman settlers, local elites, artisans, fishery workers, and Christian communities. Social stratification was pronounced, with magistrates and wealthy landowners overseeing large-scale garum production. Inscriptions attest to civic officials such as duumviri administering municipal affairs. The economy centered on industrial fish-salting complexes capable of producing up to one million liters of garum per season, supported by agriculture including vineyards and olive groves.

Residential architecture featured spacious Roman houses with peristyles, private baths, and elaborate mosaics depicting mythological themes. Diet included bread, olives, fish, wine, and fruits, consistent with Mediterranean patterns. Markets and fora facilitated trade in local and imported goods, while transport relied on riverboats and coastal shipping.

Religious life transitioned from polytheism to Christianity by the 3rd century, evidenced by a Paleochristian church. Public baths and an amphitheatre supported social and cultural activities. Lixus held colonia status under Claudius, serving as the largest urban center in Mauretania Tingitana with a complex civic structure. The city’s role evolved from a commercial center to a frontier town following Diocletian’s reforms and late antique instability.

Late Antiquity and Early Islamic Period (4th – 15th century)

After Roman withdrawal, Lixus’s population declined and contracted spatially, maintaining a smaller community of Christian and later Muslim inhabitants. Social organization adapted to reduced urban scale.

Remains

Architectural Features

Lixus is situated on a rocky promontory with terraced slopes descending toward the Loukkos River estuary and the Atlantic coastal plain. The site’s construction predominantly employs local stone masonry, including large ashlar blocks in monumental buildings and opus quadratum (regular stone blocks) in temple podiums. The urban layout reveals a complex arrangement of civic, residential, religious, and industrial zones distributed across multiple levels, adapted to the natural topography. Defensive walls from the Mauretanian and early Roman periods enclose the upper town, while a later 4th-century enclosure marks a contraction of the inhabited area. The city’s footprint expanded notably during the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, covering over 60 hectares, before shrinking in late antiquity and the medieval period. Visible remains include exposed ruins of public buildings, domestic quarters, and industrial complexes, alongside buried deposits awaiting further excavation.

Key Buildings and Structures

Theatre / Amphitheatre

Located at the base of the hill, the amphitheatre was constructed following Lixus’s elevation to Roman colony status under Emperor Claudius, around the mid-1st century CE. It is the only known ancient theatre or amphitheatre in Morocco designed to accommodate both theatrical performances and gladiatorial combats. The seating area (cavea) is shaped as half an ellipse, facing a stage. In the 3rd century CE, theatrical use ceased; the stage wall was dismantled and its stones repurposed for constructing a nearby bath complex. The surviving remains include partial seating tiers and foundational structures, though much of the superstructure has been lost.

Walls between the Theatre / Amphitheatre and the Upper Town

Defensive walls surround the upper part of the hill, dating to the Mauretanian period and extending into the early Roman era. Initially attributed to Carthaginian origins, these fortifications were constructed with large stone blocks and reflect the city’s military preparedness during the turbulent transition to direct Roman rule in the 1st century BCE and early 1st century CE. The walls incorporate towers and gates and are associated with military actions, including the suppression of a local revolt by Claudius’s forces. Portions remain visible, though some have collapsed or been reused in later constructions.

Palace of Juba II

At the summit of the hill, in the area formerly known as the “Temples quarter,” lies the palace complex attributed to King Juba II (reigned 25 BCE–23 CE). Excavations in 1948 revealed that earlier Phoenician temples were replaced by this palatial residence. The palace covers approximately 7,000 square meters, exceeding the size of the Palace of Gordianus at Volubilis. Architectural features include apses, semicircular porticoes, large windows, and triple doors, creating a combination of enclosed rooms, open porticoes, and gardens with views over the river and coast. Building F within the complex is interpreted as the main dining hall (triclinium), used for official functions. A marble throne found on site supports the royal identification. The palace includes annexed baths and other service buildings, showing architectural parallels with notable Roman residences such as the House of Augustus on the Palatine Hill and the House of the Faun at Pompeii.

Palace of Juba II: Baths

The baths within the palace complex date to the reign of Juba II and exhibit sophisticated design and decoration. Constructed in the late 1st century BCE or early 1st century CE, they include heated rooms, cold pools, and richly adorned surfaces. The architectural style and layout resemble prominent Roman examples, indicating the baths served the royal household. Remains include hypocaust heating systems, mosaic floors, and wall fragments, though preservation varies across the complex.

Residential Neighbourhood

Below the palace terraces lies a residential district with Roman-style houses identified during excavations in the 1950s. These dwellings feature columned courtyards (peristyles), spacious rooms, and private baths. Floor mosaics with geometric and figurative motifs were discovered, including mythological scenes depicting Mars and Rhea Silvia, Helios, Eros and Psyche, the Three Graces, and Bacchic processions. While many mosaics were removed and are now housed in the Museum of Tétouan, the mosaic of the god Ocean remains in situ and was restored in 2020. The houses’ construction employs stone foundations and brick walls, reflecting the wealth of inhabitants connected to local industries.

Public Baths (Thermal Baths)

Located in the northern sector of the “Temples quarter,” the public baths were built in the second half of the 1st century CE, likely during the Flavian era. The complex includes a vestibule, a large cold room decorated with a geometric mosaic featuring a medallion of the god Ocean, warm and hot rooms, and pools. Walls were adorned with painted plaster and marble revetments. The baths were constructed against the northern wall of a Corinthian atrium. They were abandoned by the end of the 3rd century CE, after which the area was converted into a cemetery. Structural remains include vaulted rooms, hypocaust heating systems, and mosaic floors, though some sections are fragmentary.

Temples and Religious Buildings in the “Temples quarter”

The “Temples quarter” covers approximately 165 meters east–west by 250 meters north–south, representing the largest excavated area of the site. Phoenician period structures include Building A, oriented east–west and constructed with megalithic blocks, and Building L, a rectangular structure dating to the 8th–7th centuries BCE. A 40-meter-long, 6-meter-wide L-shaped cryptoporticus (covered corridor) with columns supports an upper platform, possibly serving as a sanctuary with a central temple, storage rooms below, and a garden area. Punic-Mauritanian layers (4th–3rd centuries BCE) contain amphora fragments linked to fish product packaging.

Mauritanian period temples (1st century BCE to early 1st century CE) include buildings K, E, B, C, and H, characterized by rectangular floor plans and podiums built in opus quadratum. Buildings F, G, and H feature porticoes and apses with interconnected doorways; Building F is interpreted as a large temple or principal triclinium. A cistern beneath Building F’s portico measures 9.5 meters long and 3 meters deep, dating after Mauretania’s annexation in 43 CE. The quarter suffered major destruction around 40–50 CE, possibly linked to Aedemon’s revolt, but was repaired afterward.

Industrial Complex (Garum Factories)

Near the Loukkos River at the lower part of the site lies an extensive industrial complex comprising ten factories and approximately 150 basins used for producing garum, a fermented fish sauce made from tuna viscera. Founded possibly in the 5th century BCE, archaeological evidence dates the factories mainly to the 1st century BCE with expansions during the Roman imperial period. The complex could produce up to one million liters of fish sauce per fishing campaign, making it one of the largest known in the Mediterranean. Fresh water from the river was essential for cleaning and brining processes. The factories remained operational until the 5th century CE. Structural remains include stone basins, channels, and storage areas.

City Walls and Fortifications

Multiple defensive walls surround Lixus, including those from the Mauretanian and early Roman periods. These walls are constructed of large stone blocks and include towers and gates. In the 4th century CE, as the city contracted, a new enclosure was built, reflecting a defensive retraction. Additional fortifications were erected near Lixus to protect the Loukkos valley from Moorish incursions. The city’s defensive focus shifted northward after the Roman administration withdrew from the southern province. Portions of these walls survive as exposed ruins, though some sections are fragmentary or incorporated into later constructions.

Necropolises and Burial Sites

Following the abandonment of the public baths in the late 3rd century CE, the area was converted into a cemetery. Archaeological surveys have identified necropolises and tombs along ancient roads and near city gates. Burial structures include stone tombs and funerary monuments, some with inscriptions. These remains are partially preserved and provide evidence of continued occupation into late antiquity.

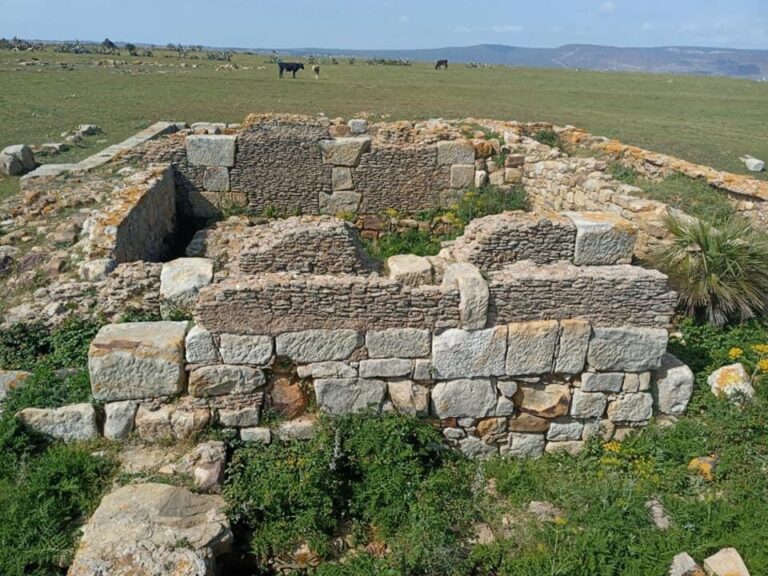

Mosque and Islamic Period Structures

Ruins of a mosque dating to the Almohad or Marinid dynasties (12th–14th centuries CE) survive on the site, indicating a Muslim community during the medieval period. The mosque is rectangular and constructed with stone masonry. Nearby are remains of a hammam (bathhouse) and a large fountain from the same period. The site was known as Tochoummis or Tchoummich during Islamic times. By the 14th century, Lixus was largely abandoned in favor of the fortified city of Larache. These Islamic structures are partially preserved as exposed ruins.

Other Remains

Cisterns for potable water storage are distributed throughout the site, including near the garum factories and residential areas. An aqueduct and drainage systems have been identified but remain only partially excavated. Houses with peristyles and private baths attest to the wealth of some inhabitants. Mosaics and wall paintings found in both residential and public buildings demonstrate artistic richness, though many mosaics were removed for museum display. Small bronze artifacts, including representations of mythological figures, have been recovered and are housed in the Archaeological Museum of Rabat.

Preservation and Current Status

The ruins of Lixus are partially preserved, with many structures surviving as exposed stone foundations and walls. The amphitheatre’s seating and stage area remain fragmentary. The palace of Juba II retains substantial architectural elements, including walls, porticoes, and bath remains, though some parts are collapsed. Residential houses survive mainly as foundations and mosaic floors, with many mosaics removed for museum conservation. The public baths and temples show partial preservation, with mosaic floors and wall fragments visible.

Islamic period structures such as the mosque, hammam, and fountain survive as ruins but are incomplete. Defensive walls are preserved in sections but suffer from erosion and vegetation growth. Restoration and conservation efforts by Moroccan heritage authorities have stabilized several areas, including the palace and “Temples quarter.” Some structures have undergone partial reconstruction using modern materials, while others remain stabilized in situ. Ongoing excavation and maintenance continue to address environmental threats and structural deterioration.

Unexcavated Areas

Significant portions of Lixus remain unexcavated, particularly in the lower terraces near the river and the presumed ancient port area. Surface surveys and geophysical studies suggest buried remains of additional residential, industrial, and infrastructure features. The full extent of the aqueduct and drainage systems is not yet explored. The “Temples quarter” covers only about 20% of the total site area, indicating substantial archaeological deposits remain underground. Future excavations are planned but are subject to conservation policies and funding availability. Modern development near Larache limits expansion of excavation zones in some directions.