Laodicea Ancient City: A Historical Urban Center in Western Türkiye

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.8

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.kulturportali.gov.tr

Country: Turkey

Civilization: Byzantine, Greek, Roman

Remains: City

Context

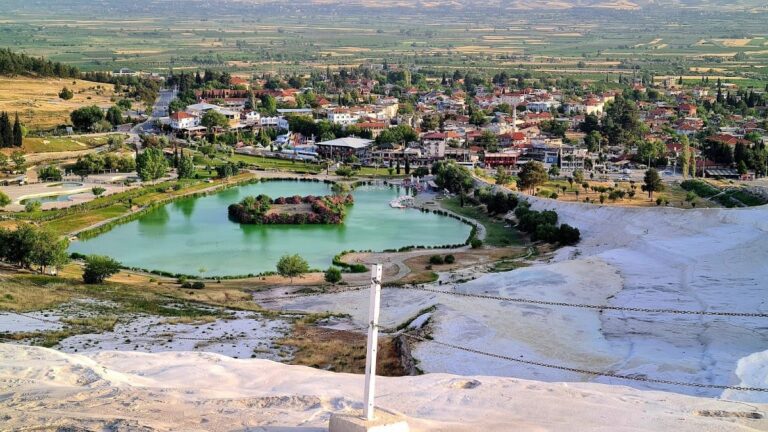

Laodicea Ancient City is situated near the modern village of Goncalı within the Pamukkale district of Denizli province in western Türkiye. The site occupies a modestly elevated position overlooking the floodplain of the Lycus River valley, adjacent to the renowned thermal terraces of Pamukkale. This valley setting provided fertile agricultural land and facilitated communication and trade routes connecting inland Anatolia with coastal regions.

Archaeological and historical evidence indicates that Laodicea was established during the late Hellenistic period and subsequently expanded under Roman administration. The city retained regional importance through the Byzantine era, serving as a religious center with an early Christian bishopric. Material culture and inscriptions attest to continued occupation into the medieval and Ottoman periods, although the precise circumstances and timing of its decline remain unresolved in scholarly discourse.

European travelers documented the ruins from the eighteenth century onward, while systematic archaeological investigations commenced in the twentieth century, led primarily by Turkish institutions with international collaboration. Substantial portions of the urban fabric, including public buildings and infrastructure, remain visible on the surface or have been revealed through excavation. Artifacts recovered from the site are curated at the Denizli Archaeology Museum, and ongoing conservation and research efforts are managed by Turkish cultural heritage authorities.

History

Laodicea Ancient City’s historical trajectory reflects the complex political and cultural transformations of western Asia Minor. Founded in the Hellenistic period, it evolved into a prosperous urban center under Roman rule and maintained ecclesiastical and administrative significance through the Byzantine era. The city experienced multiple episodes of conquest, natural disasters, and administrative reorganization, mirroring broader regional dynamics. Although its decline and abandonment are not fully understood, archaeological and textual evidence confirm continued habitation into the medieval and Ottoman periods.

Pre-Hellenistic Settlement

Archaeological excavations in the northern necropolis have uncovered evidence of indigenous habitation predating the city’s formal foundation. These findings demonstrate a continuity of settlement on the site before the Seleucid establishment of Laodicea. Earlier toponyms such as Diospolis, meaning “City of Zeus,” and Rhoas are attested in ancient sources, indicating the area’s longstanding local significance within Phrygia prior to Hellenistic urbanization.

Hellenistic Period (3rd century BCE)

Laodicea was founded between 261 and 253 BCE by Antiochus II Theos, ruler of the Seleucid Empire, who named the city in honor of his wife Laodice. The foundation involved the reorganization of preexisting settlements, including Diospolis and Rhoas, into a planned urban center. Strategically located on key trade routes linking Colossae and Hierapolis, Laodicea rapidly acquired wealth and regional prominence. The city’s political landscape was marked by instability, exemplified by the satrap Achaeus’s self-declaration as king in 220 BCE and his subsequent defeat by Antiochus III the Great in 213 BCE.

Under Antiochus III, approximately 2,000 Jewish families were relocated from Babylonia to Phrygia, many settling in Laodicea, thereby establishing a significant Jewish community. This demographic development is corroborated by Cicero’s account of Roman governor Flaccus confiscating annual gold shipments from Laodicea destined for the Jerusalem Temple. Numismatic evidence from this period includes coins bearing inscriptions and iconography related to Zeus, Asclepius, Apollo, and later Roman emperors, reflecting a syncretic religious environment.

Roman Conquest and Administration (2nd century BCE – 1st century CE)

Following Rome’s decisive victory over the Seleucid Empire at the Battle of Magnesia in 188 BCE, the Treaty of Apamea transferred control of western Asia Minor, including Laodicea, to the Kingdom of Pergamon. Upon the death of the last Pergamene king in 133 BCE, the territory was bequeathed to Rome, and Laodicea was granted the status of a free city (civitas libera). The city endured damage during the Mithridatic Wars but recovered swiftly under Roman administration.

During the late Republic and early Imperial periods, Laodicea emerged as the principal city of a Roman conventus comprising 24 municipalities. Cicero notably conducted judicial proceedings there around 50 BCE, residing for an extended period. The city’s economy thrived on trade, particularly in black wool textiles, banking, and agriculture. Prominent citizens such as Hiero contributed substantial legacies exceeding 2,000 talents, financing public buildings and cultural institutions. Laodicea was also a center of Greek intellectual life, hosting philosophers like Antiochus and Theiodas, successors of the skeptic Aenesidemus, and maintaining a renowned medical school. Polemon, a leading citizen, attained kingship over Armenian Pontus and adjacent coastal territories. The city suffered frequent seismic events, including a catastrophic earthquake during Nero’s reign circa 60 CE, which destroyed much of the urban fabric. Remarkably, the inhabitants declined imperial aid and undertook reconstruction independently.

Early Christian Period and Late Antiquity (1st century CE – 5th century CE)

Laodicea was among the earliest urban centers in Asia Minor to adopt Christianity, becoming an episcopal see in the first centuries CE. The Apostle Paul addressed the Laodicean Christian community in his epistles, and the city is enumerated among the Seven Churches of Asia in the Book of Revelation. Epaphras, a disciple of Paul, is credited with evangelizing the local Jewish population. The city’s Christian leadership included early bishops such as Archippus, Nymphas, and Diotrephes, as well as martyrs like Sagaris around 166 CE.

The Council of Laodicea, convened likely after the Council of Constantinople in 381 CE, produced sixty ecclesiastical canons that influenced church discipline and liturgical practice. Laodicea became the metropolitan see of the Roman province Phrygia Pacatiana, maintaining religious and administrative prominence into the Byzantine period.

Byzantine Period (5th century CE – 13th century CE)

Throughout the Byzantine era, Laodicea remained a significant urban center within the provincial framework of Asia Minor. The city is frequently mentioned in sources from the Komnenian dynasty. In 1119 CE, Emperor John II Komnenos and his commander John Axouch recaptured Laodicea from Seljuk Turkish control, marking a strategic military victory. Emperor Manuel I Komnenos subsequently fortified the city, which was governed by Manuel Maurozomes between 1206 and 1230.

Urban reorganization during this period involved consolidating late antique neighborhoods into a smaller, fortified core. The city suffered destruction during Turkish and Mongol invasions, resulting in a decline of the Greek Orthodox population by the mid-13th century. Control of Laodicea shifted repeatedly among Byzantines, Seljuks, and Turkish rulers. The appearance of Arabic inscriptions by 1230 reflects increasing Turkic cultural influence.

Turkish and Islamic Period (13th century CE onward)

Following the Seljuk conquest, Laodicea underwent gradual Turkification and Islamization, becoming a center for Sufi religious thought with close cultural ties to Konya. The Greek Christian population persisted into the 14th century but experienced political marginalization, primarily engaging in textile production under Muslim overlords who imposed taxation. Contemporary accounts, including that of the traveler Ibn Battuta in 1330, describe the hardships faced by the remaining Greek Christians, including exploitation and enslavement.

During this period, migrants from Laodicea founded the nearby city of Denizli. Although the site continued to be occupied through the Ottoman era, its regional prominence diminished considerably, transitioning into a modest settlement within the empire’s administrative structure.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Hellenistic Period (3rd century BCE)

The foundation of Laodicea introduced a structured urban environment inhabited by a diverse population comprising Seleucid settlers, indigenous Anatolians, and a significant Jewish community relocated from Babylonia. Social stratification included Hellenistic elites, military officials, and an emerging mercantile class. The fertile Lycus valley supported agriculture, while the city’s position on trade routes facilitated commerce and artisanal production.

Religious life was characterized by the worship of traditional Anatolian deities alongside Hellenistic gods such as Zeus, Asclepius, and Apollo, as evidenced by coinage and inscriptions. Domestic architecture likely featured mosaic floors and painted plaster walls, although direct archaeological evidence remains limited. Dietary staples included cereals, olives, grapes, and livestock products typical of the region. Markets supplied both local produce and imported goods transported via established caravan routes.

Roman Conquest and Administration (2nd century BCE – 1st century CE)

Under Roman governance, Laodicea developed into a prosperous free city and the administrative center of a conventus. The population was ethnically and socially diverse, including Roman citizens, local Anatolians, Jewish residents, and affluent elites such as Hiero and Polemon. Municipal administration was conducted by magistrates and a bouleuterion, supported by a wealthy mercantile class engaged in banking and textile manufacturing.

The economy was robust, with a particular emphasis on the production and trade of black wool textiles, agriculture, and pharmaceuticals. Archaeological remains reveal sophisticated urban infrastructure, including a large agora, two theatres, a stadium, baths, and a gymnasium complex. The city’s advanced water supply system, featuring an aqueduct with an inverted siphon and regulated by a formal water law, reflects high levels of civic organization. Domestic interiors exhibited mosaic floors, frescoed walls, and sundials, indicating refined cultural tastes. The diet was varied, incorporating bread, olives, fish, and medicinal herbs. Religious practices combined Greco-Roman deities with imperial cults. Despite frequent earthquakes, including a devastating event during Nero’s reign, the community demonstrated resilience by rebuilding without imperial assistance.

Early Christian Period and Late Antiquity (1st century CE – 5th century CE)

Laodicea’s transition to Christianity involved the establishment of an episcopal see and the integration of a Jewish-Christian population. The social fabric included clergy, Jewish families, and traditional elites adapting to new religious paradigms. Bishops such as Archippus and martyrs like Sagaris played prominent roles in ecclesiastical leadership. The Council of Laodicea codified church discipline, underscoring the city’s religious significance.

Economic activities persisted, particularly textile production and trade, though Christian ethical norms influenced social customs. Archaeological evidence documents churches and inscriptions attesting to the growing Christian community. Public architecture and urban planning adapted to accommodate ecclesiastical functions alongside traditional civic structures. Domestic decoration incorporated Christian iconography, and funerary practices evolved to include Christian rites. Markets remained active, supplying both secular and religious needs, supported by regional transport networks. Religious festivals centered on Christian liturgy, while older pagan cults gradually declined. Laodicea’s status as metropolitan see of Phrygia Pacatiana affirmed its administrative and spiritual importance within the late Roman and early Byzantine provincial system.

Byzantine Period (5th century CE – 13th century CE)

During Byzantine rule, Laodicea’s population contracted, and the urban area was consolidated into a fortified core in response to military threats from Seljuk and Mongol incursions. The Greek Orthodox community remained dominant but diminished in size. Governance combined imperial officials with local aristocrats such as Manuel Maurozomes. Economic life focused on sustaining the reduced population through textile production and local agriculture.

Archaeological evidence indicates reorganization of residential quarters and fortifications, with fewer monumental public buildings maintained. Religious life centered on Orthodox Christianity, with churches and bishopric institutions continuing despite external pressures. Markets and trade persisted on a smaller scale, adapting to shifting political boundaries. The presence of Arabic inscriptions from the 13th century reflects increasing Turkic influence. Laodicea’s role evolved from a major urban center to a fortified provincial town with strategic military importance during the Komnenian reconquest and subsequent conflicts.

Turkish and Islamic Period (13th century CE onward)

Following the Seljuk conquest, Laodicea experienced gradual Turkification and Islamization, transforming its demographic and cultural landscape. The population included Muslim settlers alongside a declining Greek Christian minority engaged primarily in textile crafts under Muslim overlords. Social hierarchy reflected Islamic governance, with Sufi religious figures influencing local culture. Economic activities centered on textile production and small-scale agriculture, supporting local markets and regional trade.

Urban structures were adapted or repurposed, with many Byzantine buildings falling into ruin. The city’s cultural connections to Konya fostered exchanges in Sufi thought. Daily life for the remaining Christian population was difficult, as recorded by Ibn Battuta, who noted exploitation and loss of political power. Transport relied on land routes linking Laodicea to emerging centers such as Denizli, founded by migrants from the city. Laodicea’s civic prominence waned, becoming a modest settlement within the Ottoman administrative framework, preserving continuity but with reduced regional influence.

Remains

Architectural Features

Laodicea occupies a gently elevated hill overlooking the Lycus valley floodplain, with an urban layout dominated by public and civic structures. The city expanded significantly during the Hellenistic and Roman periods, featuring ashlar masonry and extensive use of local travertine stone. The eastern city wall remains traceable, incorporating the Ephesus Gate. Streets are aligned with colonnades and numerous pedestals for statues or monuments, reflecting organized urban planning. The water supply system includes an aqueduct with an inverted siphon and multiple distribution tanks, demonstrating advanced hydraulic engineering adapted to the valley’s topography.

During the Byzantine period, the urban fabric contracted, consolidating late antique quarters into a smaller fortified core. Earthquake damage is evident in several structures, notably the aqueduct, which exhibits leaning arches and clogged siphon pipes. The site preserves both monumental and fragmentary remains, with some areas extensively excavated and others only partially explored.

Key Buildings and Structures

West Theatre

Constructed originally in the Hellenistic period, the West Theatre has a seating capacity estimated at approximately 8,000 spectators. It remained in use until the 7th century CE. The theatre’s stone seating banks survive nearly intact following a comprehensive restoration completed in 2022, led by Professor Celal Şimşek of Pamukkale University and a multidisciplinary team. The theatre’s semicircular design, built into the hillside, reflects typical Hellenistic architectural principles and shows evidence of continuous maintenance into late antiquity.

West (Central) Agora

The central agora covers roughly 35,000 square meters and features numerous restored columns reaching about 10.8 meters in height. The back wall extends 100 meters in length and 11 meters in height, adorned with frescoes of significant archaeological value. This expansive civic space functioned as a focal point for public gatherings, markets, and administrative activities. The scale and decorative program indicate substantial urban investment during the Roman period.

Aqueduct and Water Supply System

The aqueduct supplying Laodicea originates several kilometers from the Baspinar spring near Denizli, possibly supplemented by a more distant source. It employs an unusual inverted siphon system to traverse the valley south of the city, consisting of a double pressurized pipeline descending into the valley and ascending back to the urban area, supported by low arches near a hill summit housing the main header tank.

The first terminal distribution tank (castellum aquae) is located at the city hill’s edge, east of the stadium and South Baths complex, with visible remains. The water carried heavy calcareous deposits, causing encrustations and leaks over time. The siphon pipes, carved from large stone blocks, are partially clogged. The terminal tank contains numerous clay pipes of varying diameters distributing water to the city’s north, east, and south sectors; these pipes were periodically replaced due to clogging. A small fountain stands west of the terminal tank adjacent to a vaulted gate. A second, larger distribution terminal and sedimentation tank lies 400 meters north, connected by another travertine siphon, supplying most of the city. The aqueduct likely sustained earthquake damage, as some arches lean bodily but remain largely intact.

Stadium

Situated near the southern edge of the city, the stadium dates to the 1st century CE and was dedicated in 79 CE to Emperor Vespasian by the citizen Neikostratos. The structure features well-preserved seating arranged along two sides of a narrow valley naturally enclosed at both ends. An underground passage on the western side, used for admitting chariots and horses, survives with a long inscription above its entrance. The stadium hosted athletic contests, duels, and beast fights.

Gymnasium Complex and Twin Baths

Located immediately north of the stadium, this complex uniquely combines a gymnasium with twin baths. An inscription dates its construction to 135 CE, coinciding with Emperor Hadrian’s visit. The gymnasium connects on its north side to the southern agora and is linked to a nearby bouleuterion (Senate House). The baths comprise two separate bathing facilities, featuring vaulted rooms and hypocaust heating systems, indicative of sophisticated bathing culture.

Bouleuterion (Senate House)

The bouleuterion lies adjacent to the gymnasium complex and southern agora, serving as the city’s council or senate building. Constructed with ashlar masonry, it includes a council chamber and associated rooms. While its precise construction date is unspecified, it is associated with Roman and Byzantine urban phases.

Nymphaeum

Excavated in the 1950s and located in the city center, the nymphaeum consists of a square water basin surrounded by an Ionic colonnade. It features two semicircular fountains and two underground water storage tanks. Supplied by a vaulted aqueduct and a water reservoir in the Denizli valley, the nymphaeum functioned as a monumental fountain and water distribution point within the urban fabric.

City Walls and Ephesus Gate

The eastern city wall remains distinctly traceable, primarily constructed of ashlar masonry. Within this line, the remains of the Ephesus Gate are visible. The fortifications were reinforced during the Byzantine period, reflecting the contraction of the inhabited area into a smaller, defensible core. Portions of the walls show evidence of repair and rebuilding, possibly following earthquake damage or military conflicts.

Sarcophagi Necropolis

North of the city toward the Lycus River lies a necropolis containing numerous sarcophagi, many with lids lying nearby partly embedded in the ground. Although extensively looted over time, the surviving stone coffins provide insight into burial practices spanning multiple periods. The necropolis is associated with the northern suburban area of the ancient city.

Other Remains

Additional urban features include streets intersecting the city, flanked by colonnades and numerous pedestals for statues or monuments. Many bases for statues or commemorative markers remain along these streets. Notable recent discoveries include a marble statue of Emperor Trajan unearthed in 2019 and a Hellenistic marble sundial found in 2020, decorated with foliage motifs and inscribed with Greek names of seasons, months, and hours, though its gnomon is missing.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations have yielded numerous inscriptions, including a rare marble water law inscription dated to 114 CE. This law regulated water use from mountain sources to Laodicea, imposing substantial fines for polluting water, damaging channels, or unauthorized opening of pipes. The site has produced a variety of coins, including Hellenistic issues depicting deities such as Zeus, Asclepius, and Apollo.

Material culture includes pottery from multiple periods, such as amphorae and tableware, recovered from domestic and public contexts. Tools related to agriculture and crafts have been found alongside domestic objects like lamps and cooking vessels. Religious artifacts include statuettes and altars linked to the city’s diverse cultic practices. Collectively, these finds illuminate aspects of economic production, trade, daily life, and religious observance in Laodicea.

Preservation and Current Status

The West Theatre is well-preserved, with nearly complete stone seating following the 2022 restoration led by Pamukkale University. The aqueduct remains visible but exhibits damage from earthquakes, including leaning arches and clogged siphon pipes. The stadium retains substantial structural elements, including seating and the underground passage. The gymnasium and twin baths survive partially, with vaulted rooms and hypocaust systems identifiable.

The city walls and Ephesus Gate are fragmentary but traceable. The nymphaeum’s colonnade and water tanks remain intact. The sarcophagi necropolis is largely looted but identifiable. Restoration efforts have stabilized many structures, with some reconstructed using original materials. Excavations have been ongoing since 2002, accompanied by conservation work under Turkish cultural authorities. The site was added to Turkey’s Tentative List of World Heritage Sites in 2013.

Unexcavated Areas

Despite extensive archaeological work, large portions of Laodicea’s urban fabric remain unexcavated or only partially explored. Surface surveys and geophysical studies suggest buried remains beneath modern agricultural land and urban development. Specific districts or structures awaiting excavation are not detailed in current publications. Future research is planned but may be constrained by conservation policies and contemporary land use.