Kaunos Ancient City: A Historical and Archaeological Site in Southwestern Türkiye

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.6

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Country: Turkey

Civilization: Byzantine, Greek, Roman

Remains: City

Context

Kaunos Ancient City is located in southwestern Türkiye, positioned on a rocky promontory adjacent to the Dalyan channel, near the shores of Köyceğiz Lake and the Mediterranean Sea. The site occupies a strategic landscape where a coastal plain meets rugged terrain, with the Dalyan channel and surrounding alluvial deposits having influenced shoreline configurations since antiquity. This geomorphological setting shaped the city’s maritime access and urban development over time.

Archaeological investigations reveal continuous occupation from the Late Bronze Age through the Iron Age, with material culture reflecting Carian influences during the first millennium BCE. The settlement expanded through the Archaic and Classical periods and experienced significant transformations under Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine rule. Progressive silting of the harbor and deltaic progradation gradually restricted maritime connectivity, contributing to the city’s decline. The site preserves stratified deposits, funerary monuments, and architectural remains in varying states of preservation, with many areas still partially buried and subject to ongoing conservation and research efforts.

Documented by travelers since the nineteenth century, Kaunos has been the focus of systematic archaeological study since the twentieth century, providing valuable insights into the cultural and environmental history of southwestern Anatolia.

History

Kaunos Ancient City’s historical trajectory reflects its position at the crossroads of Carian, Lycian, Persian, Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine spheres of influence. Established by the Late Bronze Age, the city evolved through successive political regimes and cultural transformations, serving as a fortified settlement, maritime port, and ecclesiastical center. Its fortunes were closely linked to regional power shifts, imperial conquests, and environmental changes that affected its harbor and hinterland. Despite periods of prosperity, Kaunos ultimately declined due to military incursions, economic disruption, and ecological factors, leading to abandonment by the late medieval period.

The city’s documented roles include participation in regional alliances, resistance to imperial domination, and integration into provincial administrative systems. Its religious significance persisted into the Byzantine era, evidenced by its status as a bishopric. Kaunos’s layered history is illuminated by archaeological, epigraphic, and literary sources that trace its development from a Carian cultural hub to a Roman municipium and beyond.

Proto-Geometric to Archaic Period (ca. 9th–6th century BCE)

Archaeological evidence situates the earliest settlement at Kaunos in the 9th century BCE, as indicated by fragments of Proto-Geometric pottery. By the 6th century BCE, the city was a fortified community, with southeastern defensive walls and imported Attic ceramics attesting to active trade networks and cultural exchange. The ancient historian Herodotus recorded that the inhabitants claimed descent from Crete but spoke a language closely related to Carian, distinguishing them from neighboring populations. He also described distinctive social customs, notably communal wine drinking involving men, women, and children, reflecting unique cultural practices.

During this period, Kaunos was embedded within the Carian cultural milieu, developing local traditions while increasingly interacting with Greek influences. Although no architectural remains from before the 4th century BCE survive, the presence of fortifications and imported goods suggests an organized settlement with emerging civic structures.

First Persian Rule (mid-6th century BCE)

In the mid-6th century BCE, Kaunos was incorporated into the Achaemenid Persian Empire following the conquest of Caria. The city resisted the campaign led by Persian general Harpagus in 546 BCE but was ultimately subdued. Kaunos participated in the Ionian Revolt (499–494 BCE), demonstrating local opposition to Persian authority. The city’s bilingual inscriptions in Greek and Carian, dating to around 400 BCE, reveal a bilingual society maintaining native linguistic traditions alongside Greek cultural elements.

Under Persian administration, Kaunos functioned as a provincial town within the satrapy of Caria, with local elites likely mediating imperial governance. Economic activities continued to focus on agriculture, fishing, and maritime trade, supported by the city’s harbor despite early signs of silting. Civic organization is evidenced by legal inscriptions referencing councils and magistrates, indicating structured local governance within the imperial framework.

Greek Influence and Delian League Membership (5th–4th century BCE)

Following the Persian defeat in the Second Persian War, Kaunos joined the Athenian-led Delian League, marking a period of intensified Hellenization and economic growth. Tribute records show an increase from one talent to ten talents by 425 BCE, reflecting the city’s expanding prosperity and integration into the Greek maritime network. The dual use of the names Kaunos and Kbid during this era illustrates the blending of Carian and Greek identities.

The city’s economy diversified, with agriculture producing olives, figs, and pine resin, and trade exporting salted fish, slaves, and mastic used in shipbuilding. Workshops and industries likely operated within the urban fabric, supported by imported goods such as Attic ceramics. The agora emerged as a central marketplace and civic space, while fortifications underscored the city’s strategic importance. The foundation myth involving King Kaunos and his sister Byblis probably originated in this period, reinforcing the city’s Greek cultural identity.

Second Persian Rule (late 4th century BCE)

After the Peace of Antalcidas in 387 BCE, Caria, including Kaunos, reverted to Persian control. Under the satrap Mausolos (377–353 BCE), the city underwent extensive expansion, including terracing and fortification over a broad area. Greek cultural elements became dominant, with the construction of an agora and temples dedicated to Greek deities, reflecting elite patronage and civic development.

In 334 BCE, Alexander the Great conquered Kaunos, ending Persian rule and initiating Macedonian dominance. This transition marked the beginning of the Hellenistic period, during which Kaunos became a contested site among successor kingdoms vying for control of Anatolia.

Hellenistic Period and Roman Rule (4th–1st century BCE)

Following Alexander’s death, Kaunos was contested by the Antigonids, Ptolemies, and Seleucids due to its strategic coastal location. In 189 BCE, the Roman Senate assigned Kaunos to Rhodes’s jurisdiction, incorporating it into the Rhodian Peraia. A revolt against Rhodian control in 167 BCE, involving Kaunos and other western Anatolian cities, led Rome to revoke Rhodes’s administrative authority.

With the establishment of the Roman province of Asia in 129 BCE, Kaunos was assigned to Lycia near the provincial border. During the Mithridatic Wars, the city sided with King Mithridates VI in 88 BCE, expelling Roman inhabitants. Following Rome’s victory in 85 BCE, Kaunos was punished and Rhodian administration reinstated. Under Roman rule, Kaunos prospered as a maritime port, expanding its amphitheater, constructing baths and a palaestra, renovating the agora fountain, and erecting new temples, reflecting sustained urban development and integration into the imperial system.

Byzantine Era (4th–7th century CE)

With the Christianization of the Roman Empire, Kaunos became an episcopal see known as Caunos-Hegia. Bishops from Kaunos participated in significant church councils, including those at Seleucia (359), Chalcedon (451), and Nicaea (787). Ecclesiastical records from the 12th or 13th century identify Kaunos as a suffragan bishopric under the metropolitan see of Myra in Lycia, indicating its continued religious importance.

Architectural adaptations during this period include the conversion of Roman baths into a Christian church and the construction of a domed basilica on the palaestra terrace. These modifications illustrate the city’s religious transformation and ongoing, albeit reduced, occupation into late antiquity.

Decline and Abandonment (7th–15th century CE)

From the early 7th century, Kaunos endured repeated attacks by Muslim Arab forces and pirates, contributing to demographic and economic decline. In the 13th century, Turkish tribes invaded the region, fortifying the acropolis castle with medieval-style walls. By the 14th century, Turkish control over Caria precipitated a sharp reduction in maritime trade, prompting population migration and economic contraction.

The city was ultimately abandoned in the 15th century following Turkish conquest of northern Caria and a severe malaria epidemic. An earthquake further damaged the urban fabric, and natural processes gradually buried the ruins beneath sand and dense vegetation, obscuring the site until its rediscovery in the 19th century.

Modern Rediscovery and Archaeological Research (19th century–present)

Kaunos remained largely forgotten until the 19th century when Royal Navy surveyor Richard Hoskyn discovered a legal tablet referencing the city council and its inhabitants. His 1840 visit and subsequent 1842 publication renewed scholarly interest. Systematic archaeological excavations commenced in 1966 under Professor Baki Öğün and continue under Professor Cengiz Işık.

Research has extended beyond the city to nearby sites such as the Sultaniye Spa, where a sanctuary dedicated to the goddess Leto was located. Excavations have revealed stratified deposits, funerary monuments, inscriptions, and architectural remains, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of Kaunos’s long and complex history.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Proto-Geometric to Archaic Period (ca. 9th–6th century BCE)

During this early phase, Kaunos was a modest fortified settlement inhabited by a population culturally identified as Carian but claiming Cretan ancestry, as recorded by Herodotus. The community likely comprised local elites and common villagers engaged in agriculture, fishing, and small-scale trade. Social cohesion is suggested by communal customs such as mixed-age and mixed-gender wine drinking, a distinctive cultural practice.

Economic activities centered on subsistence agriculture and local exchange, supported by imported Attic ceramics that indicate wider trade connections. Fortifications imply organized defense and some degree of civic structure, though domestic architecture from this period remains archaeologically undocumented. Religious practices are not directly evidenced but may have included indigenous Carian cults.

First Persian Rule (mid-6th century BCE)

Under Persian administration, Kaunos maintained its Carian linguistic and cultural identity, as bilingual Greek-Carian inscriptions attest. The population likely included local elites who acted as intermediaries with Persian authorities. Economic life continued to focus on agriculture, fishing, and maritime trade, with the harbor facilitating regional exchange despite early silting.

Civic organization is evidenced by legal inscriptions referencing councils and magistrates, indicating structured local governance. Domestic life probably remained consistent with earlier patterns, with staple foods such as bread, olives, and fish. Religious life combined native Carian beliefs with Persian influences, though specific cults remain unidentified archaeologically.

Greek Influence and Delian League Membership (5th–4th century BCE)

Following Persian retreat, Kaunos experienced intensified Hellenization and economic expansion as a member of the Delian League. The population increasingly adopted Greek language and customs, reflected in civic institutions modeled on Greek polis structures. Social hierarchy included wealthy merchants, landowners, artisans, and possibly slaves.

The economy flourished with agricultural production of olives, figs, and pine resin, alongside maritime trade exporting salted fish, slaves, and mastic. Workshops and small industries likely operated within the city, supported by imported goods such as Attic ceramics. The agora served as a marketplace and civic center, while fortifications underscored urban prosperity. Domestic interiors featured mosaic floors and painted walls, indicating rising wealth. Religious life incorporated Greek deities alongside local cults, with temples and festivals reinforcing civic identity.

Second Persian Rule (late 4th century BCE)

During the renewed Persian control under Mausolos, Kaunos remained culturally Greek-speaking with Carian heritage. Civic life expanded with new public buildings, including an agora and temples dedicated to Greek gods, reflecting elite patronage. Economic activities intensified with urban expansion and fortification projects, though harbor silting increasingly limited maritime commerce.

Domestic life likely featured Greek-style housing with decorated interiors, while public spaces hosted social and religious gatherings. Transport remained primarily maritime, though natural changes began to restrict port accessibility. Religious practices centered on Greek polytheism, with temples serving as focal points of community life.

Hellenistic Period and Roman Rule (4th–1st century BCE)

Under Hellenistic and Roman rule, Kaunos’s population diversified, including Greek settlers, local Carian descendants, and Roman officials. Social stratification encompassed a civic elite, artisans, merchants, and slaves. Notable individuals such as the painter Protogenes and Ptolemaic secretary Zeno highlight the city’s cultural prominence.

The economy thrived as a maritime port exporting salt, pine resin, and dried figs. Urban infrastructure expanded with a large theater, baths, palaestra, and renovated agora, indicating public investment. Workshops and markets supplied a range of goods, from local produce to imported luxuries. Homes featured mosaic floors and frescoed walls, while diet combined Mediterranean staples with imported foods. Transport utilized riverine and sea routes, with two harbors facilitating trade until silting worsened. Religious life included worship of Greek and Roman deities, alongside emerging Christian influences late in the period. Kaunos held municipium status within the Roman provincial system, serving as a regional commercial and cultural center.

Byzantine Era (4th–7th century CE)

The Christianization of Kaunos transformed its social and religious landscape. The city became an episcopal see, with bishops participating in major ecumenical councils. Social hierarchy incorporated ecclesiastical leaders alongside traditional elites. Economic activity shifted toward sustaining the local population amid declining maritime trade due to harbor silting.

Public buildings were repurposed, such as the conversion of Roman baths into a church and construction of a basilica on the palaestra terrace. Domestic life adapted to Christian norms, with modest household decoration reflecting new religious symbolism. Trade and transport diminished but remained focused on local river and land routes. Religious practices centered on Christian liturgy and episcopal administration, with the bishopric playing a key civic role.

Decline and Abandonment (7th–15th century CE)

From the 7th century onward, Kaunos experienced demographic decline due to Arab raids, piracy, and later Turkish invasions. The population contracted, with many inhabitants migrating as economic opportunities waned. Social structure became more militarized, evidenced by medieval fortifications on the acropolis.

Economic activities contracted sharply, with maritime trade ceasing due to harbor silting and political instability. Agriculture likely persisted at subsistence levels. Domestic life became austere, with limited evidence of luxury goods. Transport shifted to overland routes under Turkish control, while religious life transitioned fully to Islam regionally, though Christian communities may have persisted briefly. The city lost civic status and was abandoned in the 15th century following conquest, epidemic, and earthquake damage.

Modern Rediscovery and Archaeological Research (19th century–present)

Rediscovered in the 19th century, Kaunos’s ruins have yielded layered evidence of its complex daily life and regional importance. Excavations have uncovered public buildings, domestic spaces, inscriptions, and artifacts illuminating economic, social, and religious history. Research continues to clarify household structures, trade networks, and cultural practices, restoring Kaunos’s role as a key site for understanding southwestern Anatolian antiquity.

Remains

Architectural Features

Kaunos is situated on a rocky headland and adjacent coastal plain, enclosed by extensive city walls approximately three kilometers in length. These fortifications were notably expanded and terraced during the 4th century BCE under Persian satrap Mausolos. The walls include a western gate where a statue was discovered and extend predominantly south-southeast in the southeastern sector. The acropolis, known in antiquity as Imbros, rises 152 meters above the city and is fortified with Byzantine walls, some reinforced in the medieval period, imparting a characteristic medieval appearance. Nearby lies the smaller fortress Heraklion, a 50-meter-high promontory that extended to the sea until the 5th century BCE, flanked by two ports to its south and north.

The urban layout reflects phases of expansion and contraction, with terracing and fortification works marking Persian influence. The city’s two ports—the southern port near Küçük Kale, active until the late Hellenistic period, and the inner port (now Sülüklü Göl), which could be closed by chains—document the city’s maritime infrastructure. Over time, silting reduced harbor accessibility, impacting urban function.

Key Buildings and Structures

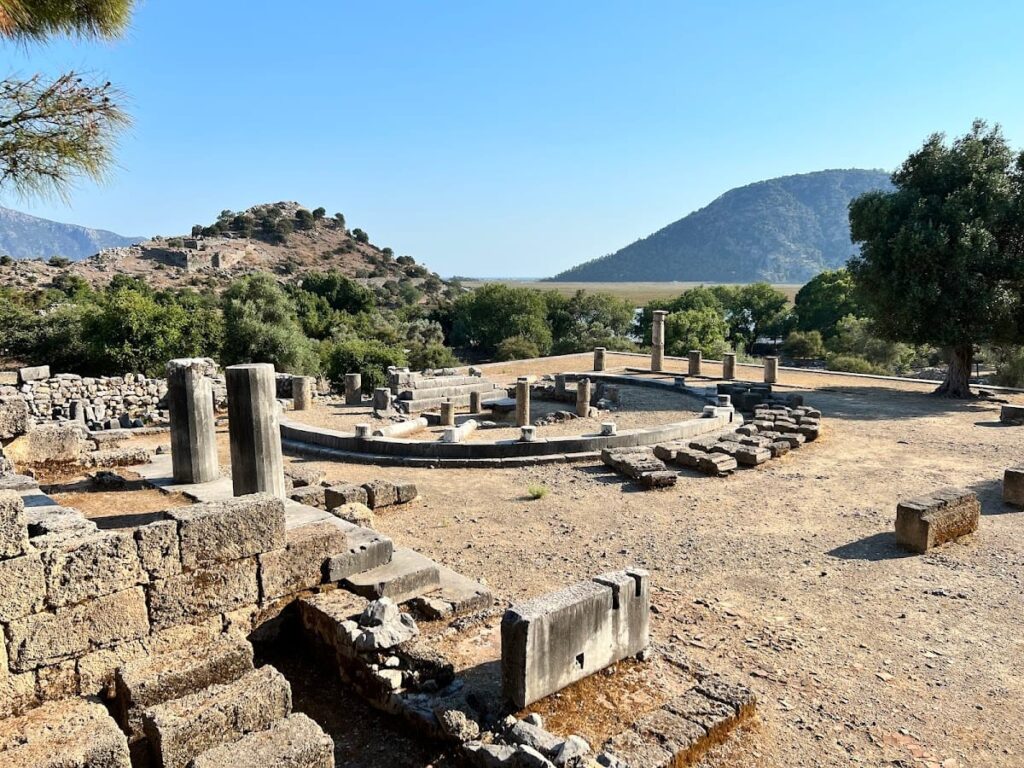

Theater

Located on the acropolis slope, the theater combines Hellenistic and Roman architectural elements. Constructed circa the 3rd century BCE and modified during Roman times, it measures approximately 75 meters in diameter and was built at a 27-degree incline. The seating area (cavea) is partially preserved, accommodating an estimated 5,000 spectators. Stone seating and stage areas survive, and the theater is occasionally used for performances today.

Palaestra and Roman Baths

The palaestra and Roman baths form a terrace complex within the city. The baths, dating to the 1st century CE, served as social and recreational facilities symbolizing Roman imperial presence. During the Byzantine period, the baths were dismantled, with the frigidarium (cold room) converted into a Christian church. The palaestra likely overlays an earlier sacred site and includes a wind measuring platform dating to circa 150 BCE. This circular structure, with a base diameter of 15.80 meters and a top diameter of 13.70 meters, was used for urban planning by assessing prevailing winds but collapsed, probably due to an earthquake.

On the palaestra terrace stands a domed Byzantine basilica from the 5th century CE, constructed on the foundations of a 4th-century building using spolia. Its interior walls were plastered and decorated with frescoes, and mosaics were uncovered nearby. This basilica is the only surviving Byzantine structure at Kaunos.

Port Agora, Stoa, and Nymphaeum

The port agora, situated near the inner harbor, functioned as a commercial and social center. It includes a stoa, a covered colonnade providing sheltered walkways, and a nymphaeum, a monumental fountain renovated during the Roman period. These stone-built structures exhibit typical Hellenistic and Roman architectural features.

Temples

Six temples have been excavated at Kaunos: two from the Hellenistic period and four from the Roman period. The most prominent is a 3rd-century BCE terrace temple, likely surrounded by columns. Inside this temple stood an obelisk (stele) depicted on ancient Kaunos coins, symbolizing King Kaunos, the city’s mythical founder. The temples are constructed primarily of ashlar masonry and include architectural elements such as column bases and stylobates.

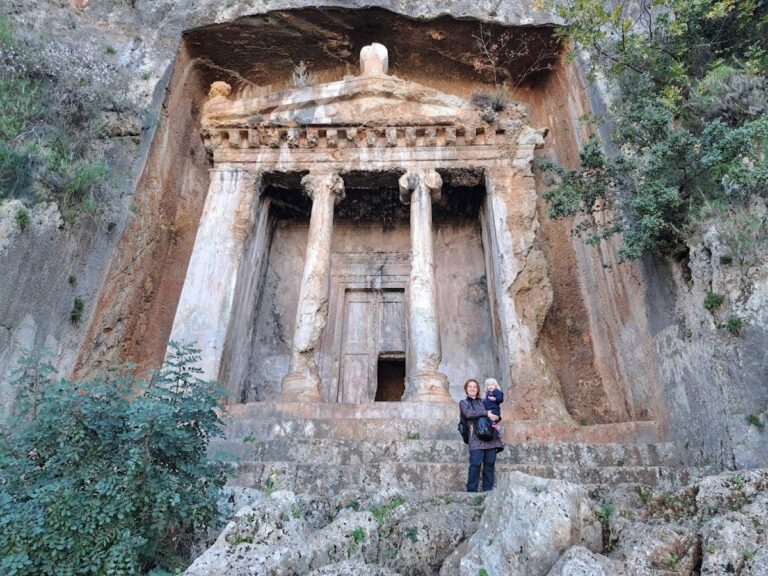

Rock Tombs

Along the Dalyan (Kalbis) river, six rock-cut tombs dating from the 4th to 2nd centuries BCE feature facades resembling Hellenistic temple fronts. These include two Ionic columns, triangular pediments, dentil friezes, and palm-leaf-shaped acroteria. Each tomb contains three stone beds for the deceased. These tombs remain prominent visual landmarks visible from the nearby town of Dalyan.

Niche Tombs at Çandır Port

Additional niche tombs carved into rock faces are located at the port of Çandır, outside the main archaeological site. These tombs represent a funerary style distinct from the riverbank tombs but have been less extensively studied.

Other Remains

Surface traces and architectural fragments indicate the presence of additional buildings and structures within the city, though details remain limited. These include remains of the wind measuring platform used for urban planning around 150 BCE, city walls and fortifications extended and reinforced during Byzantine times, and various unidentified building foundations. The two ports—the southern port near Küçük Kale and the inner port (Sülüklü Göl)—are archaeologically documented, with the latter featuring chains used to close the harbor entrance.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations have yielded artifacts spanning from the Late Bronze Age through the Byzantine period. Pottery includes Proto-Geometric fragments from the 9th century BCE, Attic ceramics from the 6th century BCE, and a range of Hellenistic and Roman tableware and amphorae, demonstrating local production and imports. Inscriptions include bilingual Greek-Carian texts from around 400 BCE, instrumental in deciphering the Carian language, and a 19th-century legal tablet referencing the city council.

Coins bearing images of King Kaunos and local symbols illustrate the city’s minting activity during the Hellenistic period. Domestic artifacts such as lamps and cooking vessels have been found in residential and workshop areas, while religious objects include statuettes, altars, and Christian liturgical items from the basilica. These finds collectively document the city’s long occupation and cultural transitions.

Preservation and Current Status

The ruins of Kaunos vary in preservation. The theater is well-preserved, retaining much of its seating and structural form. The city walls remain visible along their three-kilometer extent, though some sections are fragmentary. The acropolis fortifications, including Byzantine walls, survive with medieval reinforcements. The palaestra and Roman baths are partially preserved; the baths’ frigidarium was converted into a church, whose frescoes and mosaics survive in part.

The domed Byzantine basilica on the palaestra terrace is the only extant Byzantine building and retains interior decoration. The port agora, stoa, and nymphaeum survive in varying states, with the fountain showing Roman-period renovations. The rock-cut tombs along the Dalyan river are well-preserved and remain prominent features. Other structures, such as the wind measuring platform, are partially collapsed, likely due to seismic activity.

Excavations and conservation efforts have been ongoing since 1966 under Turkish archaeological authorities. The site lies within the Köyceğiz-Dalyan Special Environmental Protection Area, which provides ecological and archaeological protection. Some sectors remain buried or only partially excavated, with conservation measures in place to stabilize exposed remains.

Unexcavated Areas

Large portions of Kaunos remain unexcavated or only partially explored. Sediment and vegetation cover extensive areas within the city walls, limiting archaeological investigation. Surface surveys and geomorphological studies suggest buried remains beneath alluvial deposits, particularly near the ancient harbor zones. The upper acropolis area, used until late antiquity, has not been extensively excavated.

Nearby sites such as the Sultaniye Spa, with its sanctuary dedicated to the goddess Leto, have been studied, but other peripheral areas await systematic excavation. Ongoing research is constrained by conservation policies and environmental protection regulations. The absence of modern development over the site facilitates continued archaeological work under Turkish heritage management.