Hunin Fortress: A Crusader and Ottoman Stronghold in Israel

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.2

Popularity: Low

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Country: Israel

Civilization: Unclassified

Remains: Military

History

Hunin Fortress is located near the modern moshav of Margaliot in Israel. It was originally established by Crusaders in the early 12th century as a defensive stronghold along an important trade route connecting Damascus to Tyre.

The fortress was likely built around 1107 as a key part of the border defenses of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. It guarded the northern part of the Hula Valley and belonged to the large seigneurie of Toron (modern Tebnine). In its earliest phase, the fortress was constructed without a moat. The Crusaders maintained control of Hunin until 1167, when the Muslim commander Nur ad-Din captured it. Before leaving, the Crusader garrison set fire to the fortress, intentionally damaging it—a fact later verified through archaeological discoveries.

Following this destruction, the fortress was rebuilt in 1179 by Onfroy of Toron, although he died the same year. Hunin continued to be used during Ayyubid rule after the decisive Muslim victory over the Crusaders at the Battle of Hattin in 1187. However, in 1220, the fortress was deliberately destroyed by the Damascene ruler al-Malik al-Mu‘aṣṣam ‘Īṣā along with other Crusader strongholds in the Galilee region. After this event, Hunin was left abandoned for several centuries.

The name “Hunin” appears in various Crusader and later Mamluk records as part of the Toron fiefdom. By 1266, the fortress was recorded under the control of Sultan Baybars, though there is no archaeological evidence of occupation during Mamluk times. Following the decline of the fortress, the main regional trade route shifted farther south.

Centuries later, during the late 17th or early 18th century under Ottoman rule, the fortress was restored by Taqif Mutawali, a Shiite leader. This restoration was part of efforts to support the nearby Shiite village also named Hunin. The Ottomans reused the fortress’s existing foundations while adapting it to the needs of their era. The fortress remained in use until it was likely abandoned following a destructive earthquake in 1837.

Archaeological excavations carried out in the late 20th century have helped illuminate these phases of Hunin’s long history. These investigations uncovered remains dating from the Crusader period through the Ottoman restoration, revealing the fortress’s important role in the region.

Remains

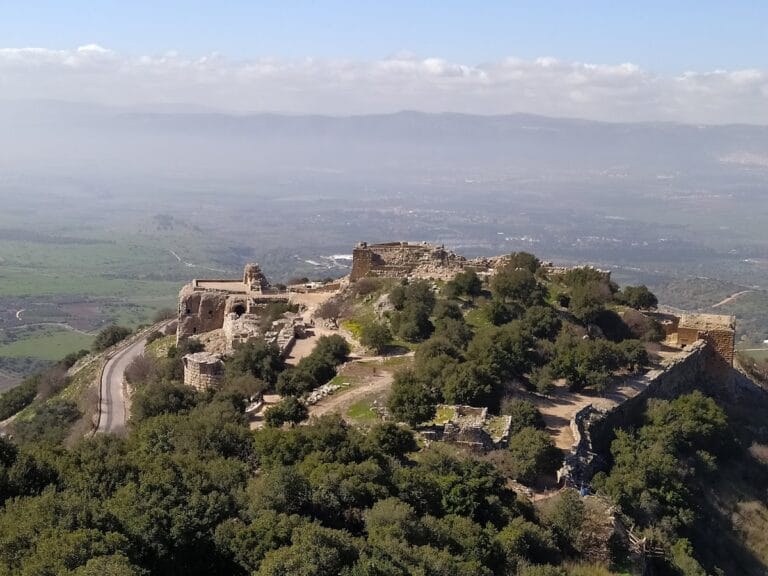

Hunin Fortress occupies roughly 5.5 dunams, an area about 90 by 70 meters, and is enclosed on three sides by a rock-cut moat averaging 12 meters wide. The eastern edge features a steep natural slope descending some 400 meters into the Hula Valley, providing natural defense. The fortress’s walls and towers were primarily constructed from well-cut stone blocks known as ashlar, featuring neatly dressed edges.

Two robust Crusader towers, part of the fortress’s initial construction phase, still survive. The western tower, nearly fully exposed, measures approximately 13 by 13 meters with walls about 3 meters thick. The eastern tower has been partially uncovered. These towers are linked by a stone wall of similar construction. While these early Crusader structures suffered significant damage from fire in 1167, their remains offer insight into the fortress’s original layout.

Later construction from the Crusader-Ayyubid period is visible in a southern wall built with reused, finely dressed stones. This wall, likely erected after the fortress’s earlier destruction, runs alongside the moat but lacks towers and appears unfinished. Latrines were discovered at each end of this southern wall, and excavations there unearthed an abundance of Ayyubid-era pottery and coins dating to around 1218, supporting historical records of the fortress’s destruction then.

Within the fortress are several ancient water cisterns cut directly into the rock to collect and store rainwater. One notable cistern beneath the Ottoman gatehouse’s northern vaulted chamber is cross-shaped and continues to accumulate water today. Some of the stones used in the fortress’s façade were repurposed from much earlier Byzantine olive presses, reflecting the area’s long history of settlement dating back to the Iron Age.

The 18th-century Ottoman restoration made extensive use of earlier Crusader and Ayyubid foundations. This phase added defensive features suited to firearm warfare, including narrow musket firing slits in the walls, and introduced vaulted chambers in the fortress’s southern section. The Ottomans also constructed a new gatehouse featuring a barrel vault, which has been restored in recent archaeology-led conservation efforts. Walls and towers received repairs and were sometimes completed during this period.

North of the moat lies the Ottoman-era cemetery of the village of Hunin, marking the area’s continuing habitation during that time. Today, the castle’s stone towers, moat, water cisterns, southern wall, and the Ottoman gatehouse remain visible, preserving physical traces of Hunin Fortress’s complex and layered past.