Gabii: An Ancient Latin Settlement Near Rome

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.3

Popularity: Very Low

Official Website: gabiipraeneste.cultura.gov.it

Country: Italy

Civilization: Roman

Site type: Burial, City, Civic, Domestic, Economic, Entertainment, Infrastructure, Military, Religious, Sanitation

Context

Gabii is situated near the modern municipality of Monte Compatri, approximately 20 kilometers east of Rome, Italy. The site occupies a strategic plateau overlooking the Aniene River valley, positioned adjacent to the ancient Via Praenestina, a principal Roman road linking Rome with Praeneste (modern Palestrina). This elevated terrain provided natural defensive advantages and ensured access to freshwater sources, factors that influenced the initial establishment and sustained occupation of the settlement.

Archaeological investigations have documented continuous habitation at Gabii from the Iron Age through the Roman Republican and Imperial periods. The earliest evidence of human presence dates to the 9th century BCE, with urban development becoming evident by the 6th century BCE. Although Gabii remained occupied into the early Imperial era, its prominence declined during late antiquity, culminating in eventual abandonment. Excavations reveal a gradual reduction in settlement density without clear archaeological indicators of abrupt destruction or economic collapse.

The site preserves substantial architectural remains, including fortifications and urban structures, many of which lie partially buried beneath modern agricultural land. Systematic archaeological research commenced in the 20th century, with intensified excavations since the 1980s uncovering stratified occupation layers. Conservation efforts prioritize the protection of exposed ruins and integration of Gabii within regional heritage frameworks, though much of the site remains under active study and is not fully accessible to the public.

History

Gabii’s historical trajectory reflects the broader political and social transformations of Latium and the Roman world. Originating as an independent Latin settlement during the early Iron Age, Gabii played a role in regional alliances and conflicts before its gradual incorporation into Roman dominion. Over subsequent centuries, the city’s significance diminished as Rome centralized power and urban development shifted, leading to its decline and eventual abandonment by the medieval period.

Early Iron Age and Proto-Urban Development (9th–7th centuries BCE)

Archaeological evidence situates Gabii’s earliest occupation in the 9th century BCE, corresponding to the Latial IIA phase. Initial habitation consisted of dispersed small communities organized into groups of approximately 100 individuals, as indicated by the extensive necropolis at Osteria dell’Osa. Distinct burial customs reveal social differentiation, including a male warrior class characterized by cremation burials in hut-urns containing miniature bronze weapons, and female burials accompanied by jewelry and spindle-whorls, suggesting textile production. These communities gradually coalesced into a proto-urban landscape by the late 9th and early 8th centuries BCE, with aerial surveys identifying six hamlets arrayed along the plateau and eastern ridge. By the end of the 8th century BCE, Gabii had consolidated into a more extensive urban center covering nearly two square kilometers, predating the foundation of Rome and marking its emergence as a significant Latin city.

Legendary Foundation and Early Latin League Period (7th–6th centuries BCE)

Ancient literary traditions attribute Gabii’s foundation either to the Latin kings of Alba Longa or to Siculi brothers named Galatus and Bins, reflecting diverse cultural influences in early Latium. Gabii was a member of the Latin League, a confederation of Latin cities that shaped regional political and military dynamics. Classical authors such as Plutarch and Gaius Julius Solinus recount that Romulus and Remus received education in Gabii under the shepherd Faustulus, emphasizing the city’s early cultural significance. During the late 6th century BCE, following Alba Longa’s destruction, Gabii resisted Roman expansion. According to Roman tradition, the city was subdued through a stratagem by Sextus Tarquinius, son of Rome’s last king Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, who feigned rebellion against Rome, gained command of Gabii’s army, and covertly eliminated its aristocracy. This facilitated Roman control without open conflict. Subsequently, the Foedus Gabinum treaty granted equal rights to inhabitants of Rome and Gabii, formalizing its integration into Roman hegemony. After the monarchy’s fall, Sextus Tarquinius sought refuge in Gabii but was killed by its citizens in retribution.

Roman Republican Period (5th–1st centuries BCE)

Following the establishment of the Roman Republic, Gabii became a Roman ally and was incorporated into the Roman administrative framework. Epigraphic evidence attests to local magistracies such as duumviri overseeing municipal governance. The city’s quarries, particularly for lapis Gabinus—a fire-resistant local stone—were extensively exploited during the late Republic, contributing to demographic decline and urban contraction. Cicero, writing in the 1st century BCE, described Gabii as a small and insignificant municipium. The poet Albius Tibullus, born in Gabii in 54 BCE, attests to the city’s continued cultural presence despite its reduced status. By the late Republic, historical sources such as Dionysius of Halicarnassus note that Gabii was largely abandoned except for areas adjacent to the Via Praenestina, with many ruins and depopulated zones. In 41 BCE, Gabii was considered as a potential meeting place for Octavian and Lucius Antonius to resolve political conflicts, underscoring its strategic location despite diminished importance.

Roman Imperial Period (1st–3rd centuries CE)

During the Roman Empire, Gabii experienced a modest revival, particularly under Emperor Hadrian, who sponsored public works including a senate-house (Curia Aelia Augusta) and an aqueduct. The city’s religious center remained the temple of Juno Gabina, constructed between 150 and 100 BCE from lapis Gabinus stone, which continued in use throughout the Imperial period. Gabii’s urban footprint contracted, concentrating around the Via Praenestina and the sanctuary complex, functioning increasingly as a statio, or road station, controlling traffic along this important route. The forum area, excavated in the 18th century, contained numerous statues and busts of deities and imperial figures, many later relocated to prominent collections such as the Borghese and the Louvre. Despite these developments, Gabii’s overall status remained modest, with quarrying activities persisting as a key economic function supplying building materials to Rome.

Late Antiquity and Decline (4th–11th centuries CE)

Gabii disappears from historical records after the 3rd century CE, though ecclesiastical documents mention its bishops until the late 9th century, indicating continued but diminished occupation. The urban fabric contracted further, and by the medieval period, the site was largely abandoned and repurposed for agriculture. The medieval tower known as the Castiglione marks the location of the ancient acropolis, symbolizing the site’s transformation from a classical urban center to a rural stronghold. Archaeological evidence does not indicate significant military events or rebuilding during this period, suggesting a gradual decline consistent with broader patterns of urban contraction in Latium during late antiquity and the early Middle Ages.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Roman Republican Period (5th–1st centuries BCE)

As a Roman ally and municipium, Gabii’s population integrated into Roman civic structures, with local magistrates administering municipal affairs. The social composition included Roman citizens, Latin families, landowners, artisans, and possibly slaves. The city’s economy was dominated by quarrying of lapis Gabinus stone, extensively exploited during the late Republic, which contributed to depopulation and urban decline. Agriculture persisted along the Via Praenestina corridor, sustaining a reduced population. Household workshops likely produced pottery and textiles, though evidence for large-scale manufacturing is limited. Dietary staples included bread, olives, wine, and locally sourced fish. Clothing followed Roman styles, with tunics and cloaks common among free citizens. The urban area contracted, concentrating around the road and remaining civic structures such as the forum, which served administrative and judicial functions. Religious practices continued at the temple of Juno Gabina and other local shrines, maintaining traditional cults alongside Roman religious customs. Cultural life included literary pursuits, as exemplified by the poet Albius Tibullus, indicating elite engagement with Roman culture. The city’s strategic location on the Via Praenestina remained important for communication and military movements despite its diminished prominence.

Roman Imperial Period (1st–3rd centuries CE)

Under Imperial patronage, particularly during Hadrian’s reign, Gabii experienced a modest revival. The population stabilized around a smaller urban core focused on the sanctuary of Juno and the Via Praenestina. The community comprised Roman citizens involved in local administration, religious service, and quarrying activities, alongside artisans and laborers. Economic life centered on quarrying lapis Gabinus for construction in Rome, supplemented by small-scale agriculture and trade servicing travelers on the road. Public amenities such as baths reflected Roman standards of hygiene and social interaction. Domestic architecture featured mosaic floors and painted walls, with household layouts including courtyards and service rooms consistent with modest urban residences. Religious life remained centered on the temple of Juno Gabina, which functioned as a focal point for civic identity and ritual. The adjacent sacred grove and healing sanctuary, evidenced by anatomical votive offerings, indicate continued religious diversity and local cult practices. Public festivals and rituals likely reinforced community cohesion. Gabii’s role evolved into that of a statio, a road station controlling traffic and providing services along the Via Praenestina. Local councils operated under imperial oversight, and the forum area, though diminished, retained symbolic importance through statues of deities and imperial figures underscoring loyalty to Rome.

Late Antiquity and Decline (4th–11th centuries CE)

After the 3rd century CE, Gabii underwent significant demographic and functional contraction. Ecclesiastical records document a Christian community with bishops active until the late 9th century, indicating continuity of religious leadership amid population decline. The social structure shifted toward a ruralized populace engaged primarily in subsistence agriculture. Economic activities were minimal, focused on local needs rather than broader trade or quarrying. The urban fabric deteriorated, with many public buildings falling into disuse. Domestic life centered on simple rural dwellings adapted from former urban structures. Clothing and diet likely reflected regional late antique rural patterns emphasizing practicality and local produce. Religious practice transitioned fully to Christianity, with churches replacing pagan temples as centers of worship and community organization. The medieval Castiglione tower marks the acropolis site, reflecting Gabii’s transformation into a fortified rural stronghold. Educational and cultural activities were limited to ecclesiastical instruction. By the medieval period, Gabii was largely abandoned as an urban center and repurposed for agriculture, consistent with broader patterns of urban decline in Latium. Its strategic importance waned, supplanted by emerging medieval settlements, and the site’s role became primarily local and agrarian.

Remains

Architectural Features

Gabii’s archaeological remains encompass extensive urban structures and fortifications spanning from the Archaic period through the Roman Imperial era. The city occupied a defensible isthmus situated between two lakes, with two streams—the Fosso dell’Osa and Fosso di San Giuliano—flanking the settlement. Long stretches of city walls constructed from squared blocks of Aniene tuff enclose the main urban area. These fortifications date to the Archaic period and delineate the original settlement boundaries. The acropolis was located on the site later occupied by the medieval Castiglione tower.

Geophysical surveys and excavations have revealed a regularized street grid beneath the surface, with the ancient Via Praenestina (formerly Via Gabina) serving as the principal urban axis. Excavations have uncovered several city blocks featuring multi-period infrastructure and urban architecture dating to the later first millennium BCE. Bridges spanning the streams integrated the city’s layout with its natural watercourses. Over time, the urban footprint contracted, concentrating around the Via Praenestina and the sanctuary complex during the Imperial period.

Construction techniques include ashlar masonry using local tuff and lapis Gabinus, a fire-resistant stone quarried nearby. Public and religious buildings frequently employed this material. The city’s architecture comprises civic, religious, and domestic structures, with evidence of economic activity such as quarries and workshops. The urban fabric exhibits phases of growth and decline, culminating in contraction and partial abandonment by the medieval period.

Key Buildings and Structures

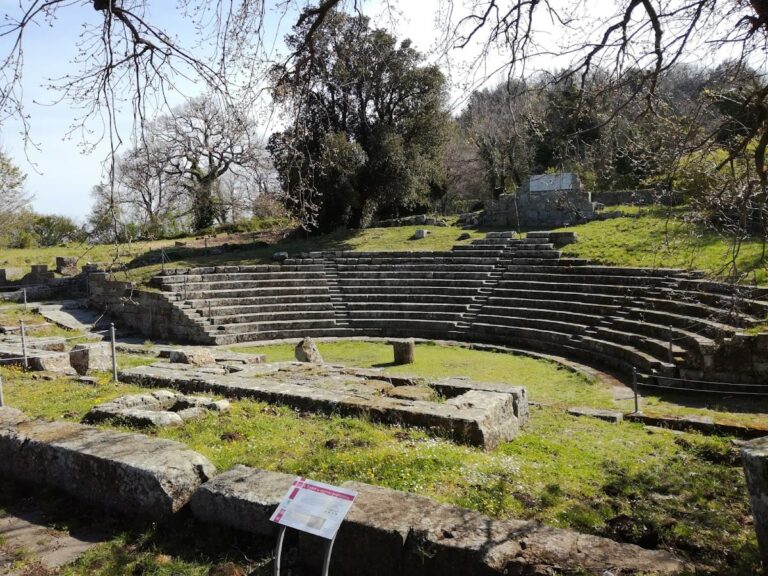

Temple of Juno Gabina

The most prominent extant structure at Gabii is the Temple of Juno Gabina, constructed between 150 and 100 BCE. The temple features a hexastyle façade with six Ionic or Corinthian columns at the front and six columns along each side, excluding the rear. It consists of a single cella (inner chamber) built entirely of lapis Gabinus stone. The temple rests on a raised podium and is surrounded at the back and sides by a colonnade of Doric columns, in front of rooms whose functions remain uncertain but may have served as temple shops or ancillary spaces.

A painted antefix bearing the inscription “IVN” identifies the temple’s dedication to Juno. Behind the temple, on the cliff side facing the road, approximately 55 pits were excavated, interpreted as planting holes for trees forming a sacred grove. This grove was sacred from the 7th century BCE and included a specially venerated tree. Adjacent to the grove, a small 4th-century BCE shrine was discovered containing caches of anatomical terra cotta votive statuettes, indicating a healing sanctuary. Additional votive pedestals inscribed to Fortuna and a pavement inscribed to Jupiter Jurarius (“of oaths”) were found, suggesting state-related ritual functions. Two other shrines were also located within the temple complex. The temple remained in use throughout the Roman Imperial period, even after the city’s decline. Excavations and publication of the temple were conducted by the Spanish School at Rome in the 1960s and 1970s.

Forum

The forum lies east of the Temple of Juno and was first excavated in 1792 by Gavin Hamilton. This rectangular plaza was bordered on three sides by porticoes, with the fourth side opening directly onto the Via Praenestina. Excavations uncovered a large cache of 38 statues and busts, including deities such as Venus, Diana, and Nemesis, alongside portraits of Roman figures ranging from Agrippa to Gordian III. Many statues were transferred to the Louvre after initial placement in the Borghese collection. Inscriptions found in the forum relate primarily to local and municipal matters, confirming its civic function as a center for administration and public gatherings.

City Walls and Fortifications

Extensive city walls constructed of squared Aniene tuff blocks date to the Archaic period. These fortifications enclosed the main urban area and incorporated the acropolis, which later became the site of the medieval Castiglione tower. The walls follow the natural topography of the isthmus, controlling access routes and watercourses. The medieval tower of Castiglione marks the ancient citadel’s location and gave its name to the former volcanic crater lake, Lago di Castiglione.

Necropolis of Osteria dell’Osa

Located north of the Via Polense near Gabii, the necropolis was in use from the 9th to the 6th century BCE. It contains approximately 600 to 700 tombs, predominantly inhumations with some cremations. The tombs are organized into 14 groups, each representing a community of about 100 individuals. Early groups from the Latial IIA phase (900–830 BCE) show evidence of a male warrior class with cremation burials in hut-urns and inhumations without weapons. Grave goods include miniaturized bronze tools and weapons, pottery, jewelry, and spindle-whorls. Distinctive burial customs differentiate northern and southern groups, such as variations in fibulae, razors, and pottery decoration. Two of the oldest inscriptions found at Gabii, an 8th-century BCE Greek inscription and a 7th-century BCE Latin inscription, were recovered here. The necropolis has provided critical data on social organization and hierarchy in Iron Age Latium.

Archaic Building Identified as Regia

Excavations east of Gabii along the ancient city wall uncovered an Archaic-period building identified as a regia, interpreted as a royal residence or administrative structure. This discovery, reported in 2010, contributes to understanding Gabii’s early political architecture. The building’s layout and construction details remain under study.

Sanctuary near City Gate

A sanctuary dating to the Archaic period was excavated near one of Gabii’s eastern city gates along the ancient walls. This sanctuary, part of recent fieldwork, includes architectural remains and votive deposits. It provides evidence of religious activity associated with the city’s fortifications and contributes to the understanding of Gabii’s ritual landscape.

Domestic and Public Buildings

Excavations near the Temple of Juno revealed rooms of uncertain function behind the colonnade, possibly serving as temple shops or multi-purpose spaces. A small shrine (sacellum) dedicated to Domitia Longina, wife of Emperor Domitian, was found near the Sanctuary of Juno Gabina. Gabii also possessed public baths, attested by literary sources and archaeological remains, patronized by Emperor Hadrian. Hadrian further sponsored construction of a senate-house (Curia Aelia Augusta) and an aqueduct, both documented by inscriptions and structural evidence.

Urban Layout and Infrastructure

Geophysical surveys and excavations since 2007 have revealed a regularized street grid beneath the surface, with substantial portions of ancient city blocks uncovered. The Via Praenestina runs through the site as the main urban axis. The city was situated on an isthmus between two lakes, with two streams (Fosso dell’Osa and Fosso di San Giuliano) flanking it and crossed by bridges. This layout reflects integration of natural and built environments. Multi-period urban infrastructure includes drainage systems and road surfaces dating from the later first millennium BCE.

Other Remains

Surface traces and architectural fragments indicate multiple shrines, including an “Eastern Sanctuary” active between the 7th and 2nd centuries BCE, likely dedicated to a female deity associated with childbirth. Remains of a medieval church lie just outside the ancient settlement. The former volcanic crater lake basin, once Lacus Gabinus or Lago di Castiglione, has been fully drained since the 17th century and is now agricultural land.

Archaeological Discoveries

Artifacts from Gabii span from the Iron Age through the Roman Imperial period. Pottery includes locally produced and imported wares found in domestic, funerary, and sanctuary contexts. The necropolis yielded grave goods such as miniaturized bronze tools, weapons, jewelry, and spindle-whorls, reflecting social differentiation during the Iron Age. Inscriptions recovered at the site include early Latin and Greek texts from the necropolis, Republican Latin inscriptions from urban contexts, and dedicatory formulas in the forum and temple precincts. Coins from various Roman emperors have been found, indicating continued occupation and economic activity into the Imperial period.

Tools and domestic objects such as lamps and cooking vessels have been recovered from residential areas and workshops. Religious artifacts include terra cotta votive statuettes from the healing sanctuary near the Temple of Juno, altars, and inscribed pedestals dedicated to deities like Fortuna and Jupiter Jurarius. These finds document ritual practices and cult activity at Gabii.

Preservation and Current Status

The Temple of Juno remains partially preserved, with its podium, columns, and cella walls extant. The forum area survives as archaeological deposits and foundations, with many statues removed to museum collections. City walls and fortifications are visible in long stretches but are fragmentary in places. The medieval Castiglione tower stands on the acropolis site, marking the ancient citadel’s location. Excavated urban blocks and infrastructure remain partially buried beneath modern agricultural land. Conservation efforts have stabilized exposed ruins, particularly at the temple complex. Some areas have undergone restoration using original materials, while others are preserved in situ without reconstruction. Environmental factors such as erosion and vegetation growth pose ongoing challenges. Archaeological investigations continue under the supervision of local heritage authorities.

Unexcavated Areas

Significant portions of Gabii remain unexcavated, especially beneath agricultural fields surrounding the known urban core. Surface surveys and geophysical studies indicate buried remains of additional city blocks, domestic quarters, and possible industrial areas. The full extent of the Archaic and later urban fabric is not yet fully explored. Modern land use and conservation policies limit excavation scope, though planned research aims to investigate these areas further.