Fort Saint-André: A Historic Military Fortification in Salins-les-Bains

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.4

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: www.fort-saint-andre.fr

Country: France

Civilization: Medieval European

Remains: Military

History

Fort Saint-André, located on Mont Saint-André near Salins-les-Bains, was originally established in 1255 by Jean de Chalon. He built the fortification to protect the extensive saltworks he had controlled since 1237. This site formed part of a wider defensive network of castles and fortifications within a 20 to 30-kilometer radius, designed to secure access to the valuable salt production in Salins.

The initial tower suffered destruction during a siege but was rebuilt in 1347. Over time, the fort gradually fell into disuse. Between 1638 and 1645, during the Ten Years’ War, the fort was reinforced with new ramparts and barracks to strengthen its defenses. After France first conquered Franche-Comté in 1668, the prince d’Aremberg further fortified the site. The fort notably resisted a 16-day siege in June 1674 during the second French conquest of the region.

Following the annexation of Franche-Comté to France, the fort underwent a major reconstruction from 1674 to 1679 under the direction of Vauban, the military engineer serving King Louis XIV. The cornerstone was laid on 18 October 1674, bearing an inscription honoring the king. In 1682, two rooms were added to house prisoners involved in the Poison Affair, including Robert de Lamiré de Bachimont and his wife.

During the French Revolution, the fort was renamed Fort-Égalité. In 1814, Austrian forces captured the fort after heavy damage, but General Marulaz intervened to prevent its destruction. The fort withstood a two-day siege in 1815. Restoration and reinforcement took place between 1818 and 1841, including transforming the front bastion into a demi-lune (a half-moon shaped fortification) and removing the north gate.

In the Franco-Prussian War of 1871, Fort Saint-André and nearby Fort Belin resisted Prussian demands despite being outnumbered. Their defense delayed the enemy advance and allowed French forces to retreat. The forts surrendered on 15 February 1871. The fort continued to serve as barracks until it was declassified in 1896, with the garrison remaining until 1919. Afterwards, the town acquired the site and transferred it to a local mineral water company.

During World War II, German occupation caused serious damage to the fort upon evacuation. Post-war plans to convert the site into a luxury hotel with a funicular were abandoned. Later, the fort hosted summer camps. Since 1922, the fort and its dependencies have been protected as a classified historic site, with additional monument listings in 1991 and 1993.

Remains

Fort Saint-André occupies over three hectares on Mont Saint-André at 604 meters altitude, overlooking the west of Salins-les-Bains. Its layout follows Vauban’s design principles, featuring a western front with a curtain wall flanked by two demi-bastions. This front is protected by a fausse braie, an outer defensive wall, which includes a bastion.

The original defensive ditch was widened and includes a covered path. The first entrance is located on the left flank of the bastion and accessed by a drawbridge crossing the fausse braie. A second entrance, still in use today, lies further north within the fausse braie and is protected by two successive drawbridges on the left flank of a small bastion.

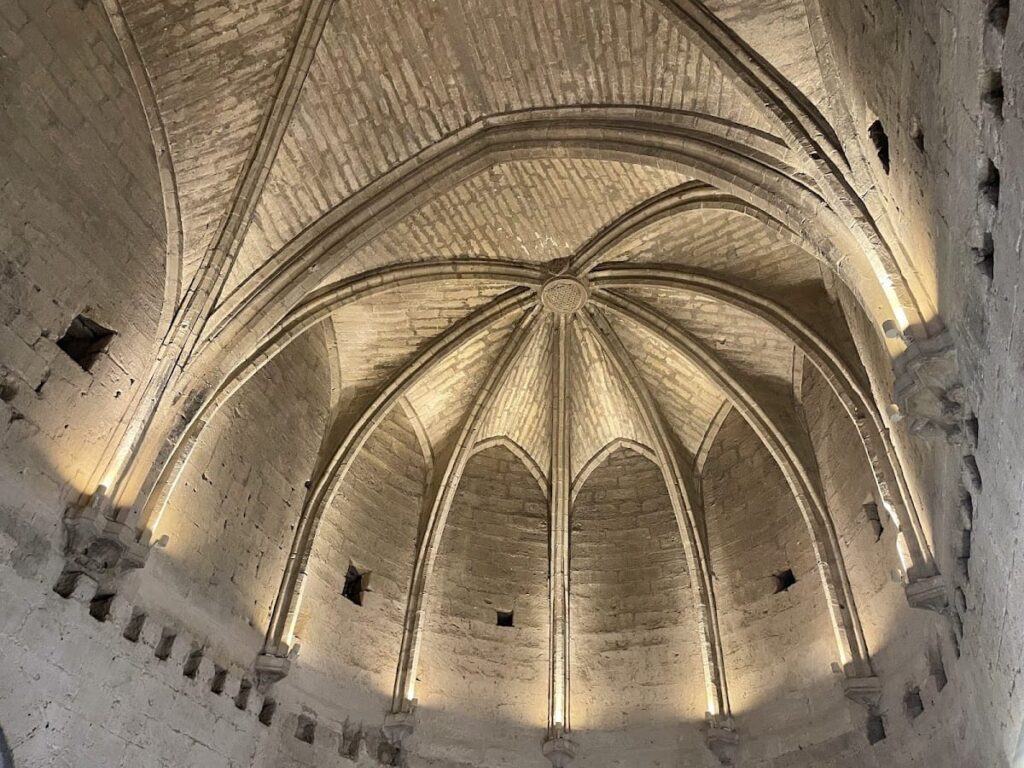

The fort’s enclosure follows the natural contours of the site. A rocky outcrop on the southeast is topped by a small fortification known as the “nid d’aigle” or eagle’s nest redoubt. Inside the fortification stand two two-story barracks designed to accommodate 500 soldiers. Other structures include a powder magazine capable of storing 40 tons of explosives, an arsenal, two cisterns, stables, a chapel, and the governor’s pavilion.

The strategic path within the fort was paved in 1736. The fort’s western front suffered damage during the 1814 Austrian siege, particularly to the curtain wall and bastions. In the 19th century, restorations transformed the western bastion into a demi-lune and removed the northern gate. The fort’s buildings and fortifications have been preserved as historic monuments, though some recent modifications are excluded from classification.