Eleutherna: An Ancient City on Crete with a Rich Historical Legacy

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.6

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: mae.uoc.gr

Country: Greece

Civilization: Byzantine, Greek, Roman

Remains: City

Context

Eleutherna is situated inland on the island of Crete near the contemporary village of Eleftherna. The archaeological site occupies a steep ridge and an adjacent plateau on the northern slopes of the Psiloritis mountain range. This elevated position commands views over surrounding valleys that historically connected the island’s interior to the northern coastal plain, facilitating control over inland routes and access to maritime points.

History

Eleutherna’s historical trajectory spans from the Late Bronze Age through the early medieval period, reflecting the complex cultural and political transformations of Crete. Initially integrated within the Minoan civilization, the site transitioned into a fortified Dorian city-state during the Greek Dark Ages and Classical era. It played a notable role in regional military and political affairs during the Hellenistic period. Roman conquest brought urban redevelopment and economic prosperity, which declined following natural disasters and Arab incursions. The city’s eventual abandonment in the early medieval period marked the end of its continuous habitation, though its ecclesiastical legacy persisted in later centuries.

Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age (Late Minoan III to Protogeometric Period)

During the Late Bronze Age, Eleutherna was part of the Minoan cultural sphere, as evidenced by extensive finds on Pyrgi hill, including hundreds of obsidian artifacts such as flakes, cores, and blades dating to the Early Minoan period. Pottery assemblages span from Early Minoan through Late Minoan IIIc, with imports from notable Minoan centers like Vasiliki, Pyrgos, and Agios Onoufrios, indicating active trade or cultural exchange networks. Ritual pits carved into the bedrock on the western side of the acropolis contained Late Minoan IIIc ceramic fragments, drinking vessels, cooking utensils, and animal bones predominantly from sheep and goats. These pits also yielded figurines, including a seated female figure interpreted as a nurturing kourotrophos deity and a painted bull sculpture, suggesting symbolic or ritual practices involving animal imagery.

These ritual deposits, dated from Late Minoan IIIc through the Proto-Geometric period, appear to have been associated with communal feasting or coming-of-age ceremonies, possibly conducted in open-air settings without permanent architectural structures. The continuity of such ritual activity into the early Iron Age marks a cultural transition from Minoan to early Greek influences at Eleutherna.

Geometric and Archaic Period (9th–6th centuries BCE)

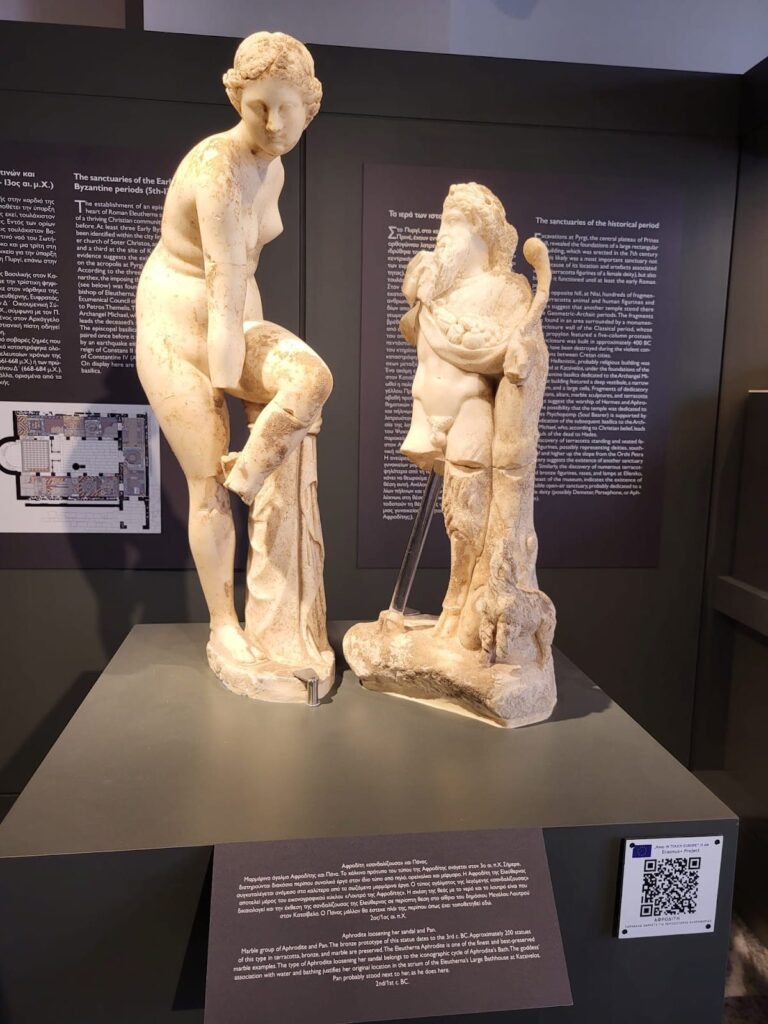

Following the Greek Dark Ages, Eleutherna was established by Dorian settlers in the 9th century BCE on a naturally defensible ridge overlooking key routes connecting major Cretan centers such as Kydonia and Knossos, as well as the Idaion Andron sanctuary cave on Mount Ida. The central plateau of Pyrgi hill functioned as the city’s religious and political nucleus, as demonstrated by numerous inscriptions discovered within the ruins of an early Byzantine church constructed atop an earlier tetraconch structure. A temple erected in the 7th century BCE on this plateau remained in continuous use until the 2nd century CE, underscoring the site’s enduring religious significance.

The necropolis at Orthi Petra contains burials from the Geometric and Archaic periods, including a remarkable double tomb dating to the 7th century BCE. This tomb contained over 3,000 gold leaves and features the earliest known depiction of the bee as a goddess, reflecting complex religious symbolism and social stratification. By the 4th century BCE, Eleutherna had achieved sufficient political autonomy to mint its own coinage, indicating economic development and regional influence. The city was also known by the name Apollonia, linked to the worship of Apollo Eleutherios as its patron deity. The toponym Eleutherna may derive from the epithet of Demeter Eleuthous or from a mythological figure named Eleutheras, one of the Curetes, reflecting the city’s mytho-religious identity.

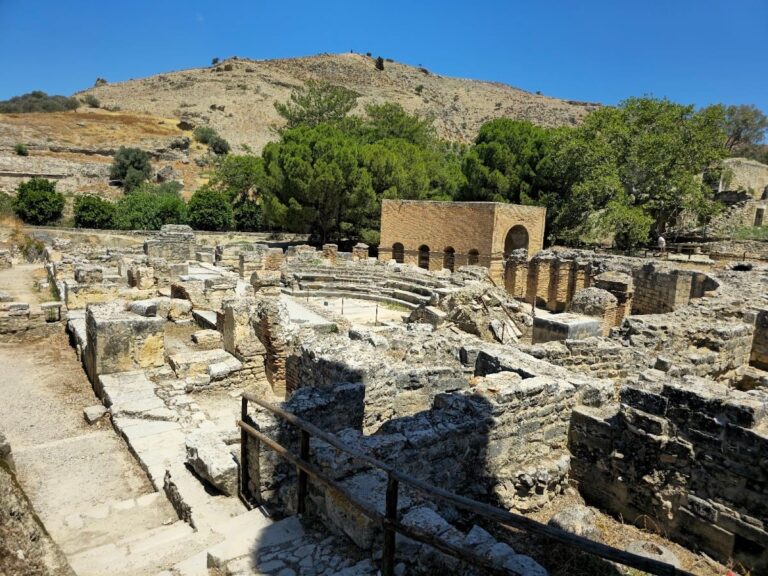

Classical and Hellenistic Period (5th–2nd centuries BCE)

During the Classical and Hellenistic periods, Eleutherna was actively engaged in the shifting political landscape of Crete. In the First Cretan War (205–200 BCE), the city initially allied with Knossos and Gortys but later shifted allegiance under pressure, ultimately siding with King Philip V of Macedon against Rhodes. In 220 BCE, Eleutherna accused the Rhodians of assassinating its leader Timarchus, an event that precipitated the Lyttian War, involving complex alliances and military confrontations. Archaeological evidence from this era includes fortification walls on Pyrgi hill, constructed in a style comparable to those at Aptera and Falasarna, dating to the 3rd–2nd centuries BCE. Large quantities of Hellenistic pottery and finely crafted drinking vessels found near the tetraconch suggest significant human activity, possibly related to ritual or elite consumption practices. The acropolis featured a defensive tower (pýrgos) overseeing the narrow access route, from which the hill derives its name.

Roman Conquest and Imperial Period (1st century BCE–4th century CE)

Eleutherna was conquered by Roman forces in 68/67 BCE through a stratagem recorded by Cassius Dio. The city’s defenders attempted to sabotage a brick tower by applying vinegar to weaken its mortar, but the Roman general Metellus ultimately captured the settlement and imposed heavy tributes. Under Roman rule, Eleutherna underwent extensive urban transformation, including the demolition of Hellenistic structures and the construction of luxurious villas, public baths equipped with hypocaust heating systems, and other civic buildings. Inscriptions dedicated to Agrippa Postumus and the presence of Roman pottery imports confirm the city’s integration into the Roman imperial system.

Archaeological layers indicate that the bathhouse and the tetraconch were abandoned prior to the earthquake of 365 CE, which caused widespread destruction in the region, including the ruin of three Roman houses. Urban infrastructure such as paved roads and large cisterns attest to the city’s developed status during this period. The presence of hydraulic mortar, marble veneer, and clay floor tiles further illustrates the level of Roman architectural investment.

Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine Period (4th–7th centuries CE)

Following the 365 CE earthquake, evidence of habitation on the central plateau diminishes until the 7th century CE, when a large church was constructed near the old acropolis atop the earlier tetraconch structure. The acropolis fortifications were renovated during this period, likely as a defensive response to increasing Arab raids. Four additional churches were erected on the lower terraces of Pyrgi hill during the 5th and 6th centuries, indicating sustained religious activity. The basilica of Archangel Michael at Katsivelos, dated by inscription to between 430 and 450 CE, was built on the site of an earlier Hellenistic sanctuary but was destroyed in the 7th century.

Eleutherna became the seat of a Christian bishopric, with Bishop Euphratas credited for constructing a large basilica in the mid-7th century CE. The necropolis of Orthi Petra contains tombs from this era, including ceramic-covered and box-shaped graves, reflecting evolving funerary customs. These developments illustrate the city’s transformation into a religious center during Late Antiquity and the early Byzantine period.

Arab Rule and Final Abandonment (8th–9th centuries CE)

In the late 8th century, Eleutherna suffered from Arab raids, including attacks attributed to Caliph Harun al-Rashid. An earthquake in 796 CE further damaged the city’s infrastructure. These combined pressures, alongside the Arab conquest and subsequent rule of Crete, led to the final abandonment of Eleutherna as a significant settlement. The population likely dispersed or relocated to more secure locations under Arab control.

Despite the physical decline, Eleutherna’s ecclesiastical legacy endured. During the Venetian occupation of Crete, a Catholic diocese was established at the site, which survives today as a Roman Catholic titular bishopric.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Geometric and Archaic Period (9th–6th centuries BCE)

During the Geometric and Archaic periods, Eleutherna functioned as a fortified Dorian city-state situated on a defensible ridge controlling vital land routes between major Cretan centers and the Idaion Andron sanctuary. The population was predominantly Dorian Greek, with a social hierarchy likely comprising aristocratic landowners, religious elites, artisans, and common citizens. Epigraphic evidence attests to the presence of civic officials, though individual names remain limited.

The economy was primarily agrarian, supported by fertile soils and pastures, supplemented by craft production and local trade. The city’s minting of coins in the 4th century BCE reflects economic autonomy and regional influence. Pottery workshops and small-scale manufacturing likely catered to both domestic consumption and external trade. Residential architecture on the plateau probably consisted of modest dwellings with storage and living spaces, although direct architectural evidence is limited.

Dietary practices included cereals, olives, and livestock products, consistent with regional agricultural patterns. Funerary customs at the Orthi Petra necropolis reveal elaborate burial practices, including richly adorned tombs with gold leaf and symbolic motifs such as the bee goddess, indicating religious beliefs and social stratification. Religious life centered on a temple constructed in the 7th century BCE on Pyrgi hill, dedicated to Apollo Eleutherios or possibly Demeter Eleuthous, with ritual activities reinforcing civic identity and social cohesion.

Classical and Hellenistic Period (5th–2nd centuries BCE)

In the Classical and Hellenistic eras, Eleutherna expanded its fortifications and engaged actively in regional politics and warfare. The city aligned with Macedonian interests during the First Cretan War and the Lyttian War, reflecting its strategic and military significance. The population remained primarily Greek, governed by a ruling elite responsible for military and diplomatic affairs. Archaeological evidence of fortified walls and a tower guarding the acropolis entrance reflects heightened defensive concerns.

Economic activities diversified, including intensified agriculture, artisanal pottery production, and participation in regional trade networks. The discovery of abundant Hellenistic pottery and fine drinking vessels near the tetraconch suggests ritual or elite consumption practices. Urban development included public buildings and religious sanctuaries, indicating an organized civic structure with magistrates and possibly military commanders. Domestic life likely featured more complex housing with decorated interiors, although specific details remain sparse. Diet remained based on local agricultural products, supplemented by imported luxury goods. Transportation relied on established land routes, with the acropolis tower symbolizing control over access.

Religious observance persisted around the temple on Pyrgi hill, with cults of Apollo Eleutherios and other deities maintaining social cohesion. Eleutherna evolved into a fortified polis balancing local autonomy with broader Hellenistic geopolitical dynamics.

Roman Conquest and Imperial Period (1st century BCE–4th century CE)

The Roman conquest in 68/67 BCE integrated Eleutherna into the Roman provincial system. The population comprised local Greeks alongside Roman settlers and administrators. Inscriptions referencing dedications to Roman figures such as Agrippa Postumus indicate imperial patronage and civic loyalty. Social stratification included wealthy villa owners, artisans, and laborers.

Economic life flourished with large-scale construction of luxurious villas, public baths equipped with hypocaust heating, and infrastructure such as aqueducts and paved roads. Archaeological remains attest to workshops producing pottery and other goods, supporting both local consumption and regional trade. Diet incorporated Mediterranean staples—bread, olives, fish—augmented by imported products evidenced by Roman pottery fragments. Domestic architecture featured mosaic floors and painted walls, reflecting Roman aesthetic preferences and wealth. Public buildings served administrative, social, and religious functions, while baths facilitated communal life. Markets likely offered a variety of goods, including imported luxury items transported via coastal ports connected to Eleutherna by road.

Religious practices gradually incorporated Roman imperial cults alongside traditional Greek deities. The city maintained civic institutions under Roman governance, with magistrates and local councils administering daily affairs. Eleutherna’s status as a municipium or civitas is implied by coinage and inscriptions, underscoring its integration into the empire’s administrative framework.

Late Antiquity and Early Byzantine Period (4th–7th centuries CE)

Following the 365 CE earthquake, urban activity declined, but by the 5th and 6th centuries CE, Eleutherna experienced religious revitalization with the construction of multiple churches on Pyrgi hill’s terraces. The population was predominantly Christian, organized under ecclesiastical leadership including Bishop Euphratas. Social hierarchy incorporated clergy, landowners, and common villagers.

Economic activities shifted toward sustaining local religious communities and agriculture, with less emphasis on urban luxury. Archaeological evidence of large basilicas and fortified acropolis walls suggests a community preparing for external threats, likely Arab raids. Domestic spaces were simpler, with fewer luxury decorations, reflecting broader Late Antique trends. Diet remained agrarian, supported by local produce. Markets and trade diminished but persisted at a reduced scale, focusing on essential goods. Transportation adapted to defensive needs, with fortified routes and limited long-distance commerce.

Eleutherna’s civic role transformed into a Christian bishopric, serving as a religious center rather than a political or economic hub. The renovation of fortifications and ecclesiastical buildings indicates a community adapting to changing geopolitical realities while maintaining continuity of spiritual life.

Remains

Architectural Features

Eleutherna’s archaeological remains encompass a broad chronological range from the Late Bronze Age through the early medieval period. The principal concentration of structures lies on the central plateau of Pyrgi hill and its surrounding slopes. The site includes religious, military, residential, and funerary architecture constructed primarily from local limestone and ashlar masonry. The urban layout centers on a fortified acropolis with defensive walls and a tower controlling access routes. Over time, the settlement experienced phases of expansion and contraction, with significant Roman-era redevelopment and later Byzantine fortification renovations. Preservation varies from well-maintained walls and foundations to fragmentary elements overlain by subsequent constructions.

Construction techniques differ by period, including ashlar blocks alternating with fieldstones in the Archaic temple walls, rock-cut foundations for Hellenistic fortifications, and Roman use of hydraulic mortar and marble veneer in public buildings. Religious structures demonstrate continuity and reuse, with early temples supplanted or incorporated into Byzantine churches. Defensive works were maintained and adapted from the Hellenistic through Byzantine periods. Roman residential and public buildings feature hypocaust heating systems and paved roads, though many were damaged or abandoned following the 365 CE earthquake.

Key Buildings and Structures

Temple on the Central Plateau

Constructed in the 7th century BCE, the temple on Pyrgi hill’s central plateau remained in use until the 2nd century CE. Built directly on natural limestone bedrock, it employed ashlar masonry combined with fieldstones. The south wall, nearly 10 meters long and 0.65 meters wide, features alternating ashlar blocks and rough stones as fillers. The eastern wall, a later addition, survives in segments approximately 5.9 meters long and 0.77 meters high, composed of two courses of ashlar blocks. A north wall fragment, about 4.4 meters long and nearly 1 meter high, was found partially beneath later church ruins and shares construction traits with the south wall but exhibits stylistic differences.

Evidence indicates additional walls on the western side, constructed in later phases using ceramic sherds as fillers. The temple’s original layout is partially obscured by a 3rd–4th century CE early Byzantine church built atop an earlier tetraconch structure on the same site. The south wall connected to a paved area to the north, suggesting the temple was part of a larger complex. Some wall sections are now lost but inferred from ashlar block arrangements.

Early Byzantine Church (3rd–4th Century CE)

This church was erected on the central plateau during the early Byzantine period, constructed over the remains of an older tetraconch building. It overlays parts of the earlier Archaic temple, indicating continuity and reuse of the sacred site. Excavations nearby uncovered large quantities of Hellenistic pottery, demonstrating continued activity in the area prior to the church’s construction. The church’s architectural remains include foundations and wall fragments integrated with earlier structures.

Roman Bathhouse on the Central Plateau

Dating to the 1st century CE, the Roman bathhouse on the central plateau features two hypocaust heating systems. Archaeological finds include clay spacers, marble veneer, hydraulic mortar, and clay floor tiles. Four bronze coins dated between 296 and 310 CE were discovered within a soil layer associated with the bathhouse, indicating abandonment before the 365 CE earthquake. The bathhouse was constructed following the leveling of earlier Hellenistic structures and was supplied by an aqueduct, reflecting significant Roman investment in urban infrastructure.

Fortifications and Tower on Pyrgi Hill

Defensive walls on the western slope of Pyrgi hill date to the Hellenistic period, built on foundations set within a rock trench. The masonry style resembles fortifications at Aptera and Falasarna. A fortification tower (πύργος, pýrgos) overlooks the narrow access route to the acropolis, giving the hill its name. These fortifications were renovated in the 7th century CE, likely as protection against Arab raids. The tower and walls show continuous use from the Hellenistic through Byzantine periods, with surviving masonry and foundation remains.

Ritual Pits on the Western Side of the Acropolis

Three ritual pits excavated west of the acropolis date from the Late Minoan IIIc to the Proto-Geometric periods. Pit A, approximately 0.8–0.9 meters deep and 1.02 meters in diameter, contained clay fragments, cooking and drinking vessels, animal bones, a brazier with burning signs, and figurines including a seated female kourotrophos and a painted bull sculpture. Pit B, carved into rock and measuring 1.63 by 1.34 meters, held pottery from the Subminoan to Proto-Geometric periods, mainly cooking and drinking vessels. Pit C, smaller at 0.5 by 0.43 meters and divided by dressed stones, contained stone tools, animal bones, and ceramic kitchen and drinking vessels. These pits were used in an open-air context without associated architecture, likely for ritualized communal eating or social integration ceremonies.

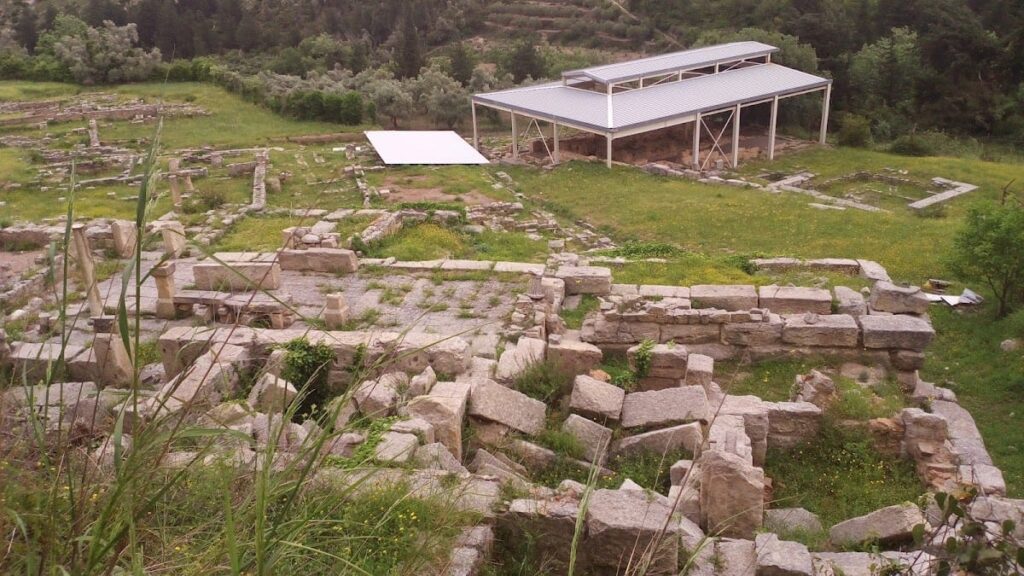

Basilica of Archangel Michael at Katsivelos

Located on the eastern side of Prines hill, this three-aisled basilica was constructed between 430 and 450 CE on the site of an earlier Hellenistic sanctuary. The basilica features rich mosaic decoration and was destroyed in the 7th century CE. The remains include foundations and wall fragments preserved within the archaeological area, now protected by a modern shelter.

Double Church of Savior Christ and John the Baptist

This medieval complex, situated at the eastern edge of the settlement, consists of two connected churches. The Church of the Savior, dating to the 12th century CE, has a free-cross plan with a dome and preserves a Pantokrator fresco in the dome. The adjoining Church of John the Baptist was built in the 16th century. The complex shows multiple architectural interventions over time and likely functioned as a small monastery during the Late Middle Ages. Structural remains include walls, domes, and fresco fragments.

Roman Houses and Public Buildings

Three Roman houses excavated at Eleutherna were destroyed by the earthquake of 365 CE. These residential buildings exhibit typical Roman architectural features. A large public building, probably of Hellenistic origin from the 2nd to 1st centuries BCE, was reused during the Roman period in the 1st and 2nd centuries CE. The site also includes a paved stone road and other Roman architectural remains such as walls and foundations, indicating an organized urban layout.

Necropolis of Orthi Petra

The necropolis on the western part of Prines hill dates from the Late Protogeometric period (circa 870/850 BCE) to the Archaic period (circa 600/550 BCE). Excavations revealed numerous tombs, including a double tomb containing over 3,000 gold leaves and the earliest known depiction of a bee as a goddess. The necropolis contains burials of females identified as a matrilineal dynasty of priestesses based on dental epigenetic analysis. Tomb types include chamber graves and cist burials, with grave goods preserved in situ.

Other Archaeological Features and Infrastructure

Large limestone quarries at Peristere hill supplied building materials for Eleutherna. A Hellenistic stone bridge is located north of Prines hill. Massive water cisterns lie below and west of the fortification tower on Pyrgi hill. Roman and early Byzantine cemeteries with tile-covered and box-shaped tombs from the 6th and 7th centuries CE have been excavated. Surface traces of walls and architectural fragments indicate additional unexcavated or poorly preserved buildings. Low walls and floor layers have been recorded in various parts of the site, though their function remains undetermined. Possible cisterns and drainage systems have been identified but not fully excavated.