Dubno Castle: A Historic Fortress in Ukraine

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.6

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: zamokdubno.com.ua

Country: Ukraine

Civilization: Medieval European

Remains: Military

History

Dubno Castle stands in the town of Dubno, Ukraine, originally established by the Volhynian people. Its origins reach back to the 10th century when it served as a fortified center known as a detinets, protecting the settlement and anchoring chronicled accounts of the town during this early medieval period.

This initial fortress suffered destruction following the Mongol invasions of 1240–1241, which devastated many territories in the region. In the late 14th to early 15th century, the site was revived when Prince Fedor Ostrogski erected a new fortification composed primarily of wood and earthworks. This enclosed structure was reinforced by earthen ramparts and a wooden palisade, creating a defensive enclosure that surrounded residential and utility buildings, marking a transition from purely military fort to a settled seat.

As wooden defenses proved vulnerable, greater stone fortifications became necessary. Around 1492, Prince Konstantin Ostrogski initiated construction of a stone fortress positioned on higher, more defensible terrain. This new foundation laid the groundwork for further expansions and significant renovations in the following centuries.

The early 17th century brought notable enhancements under Castellan Janusz Ostrogski, who remodeled the castle in the late Renaissance style. During this period, two bastions equipped with watchtowers were added, reflecting contemporary European military architecture focused on protecting against artillery advances.

Throughout its history, Dubno Castle remained in private hands, passing through several noble families, including the Ostrogski, Zasławski, Sanguszko, and Lubomirski lineages. Its ownership shifted notably in the late 19th century when it was sold to military authorities, leading to its use by various occupying armies over the decades. These included Russian Imperial, Austro-Hungarian, forces of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, Polish troops, Soviet Soviet military, and German forces during World War II.

Despite numerous attempts by Tatars, Cossacks, Russians, and Swedish armies to capture the fortress, it withstood these sieges except during the Second World War, when German and Soviet forces managed to take control. During this tumultuous time, the castle served as a prison for the Soviet NKVD secret police, and in 1941, a tragic massacre of prisoners occurred within its walls, which precipitated further violent events in the town.

Archaeological work beginning in 1995 under Dr. I.K. Sveshnikov confirmed the historical continuity of Dubno as a princely seat from the late 10th to early 11th centuries, enriching understanding of the castle’s earlier phases and its long-standing regional importance.

Since Ukraine’s independence in 1991, the castle has transitioned from military use and now functions as a museum, preserving its layered history and cultural heritage.

Remains

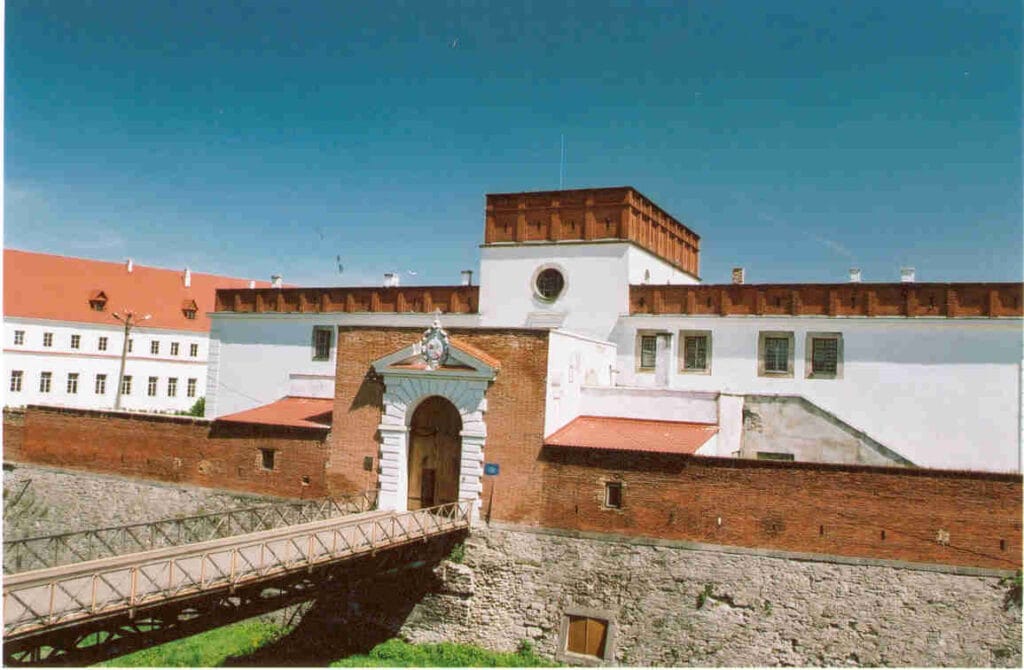

Dubno Castle is situated prominently on a headland along the Ikva River, which curves around the site on two sides, with marshlands naturally protecting the remaining perimeters. This location offered strong natural defenses complemented by manmade fortifications. The castle follows a trapezoidal layout shaped primarily during the early 17th century, embracing defensive principles inspired by the Italian bastion fort style, designed to withstand gunpowder artillery.

Two large bastions dominate the fortifications, each featuring rounded corner towers called cavaliers, which are topped with dome-shaped roofs. These bastions flank a central curtain wall, creating a strong defensive perimeter. The lower portions of these walls consist of sandstone blocks, providing a solid base, while the upper sections are built of brick, demonstrating a combination of durable and lighter materials.

Surrounding the castle is a deep moat, continuously filled with water diverted from the Ikva River. On the outer edge of this ditch, a stone counterscarp—a secondary defensive wall—strengthens the moat’s protection against attackers.

Access to the inner fortress is through a vaulted gatehouse dating to the 16th century, which, despite undergoing several later alterations, preserves a richly decorated portal. The entrance displays rustic ornamentation, a triangular pediment, and prominently features the coat of arms of the Ostrogski-Zasławski families crowned by a princely mitre, indicating the noble heritage of the castle’s builders and owners.

Immediately beyond the gatehouse lies a vaulted passageway set within a three-story structure that includes an attic. This building currently houses the historical museum but was originally integral to the castle’s entrance complex.

Within the defensive ring of the fortress, vaulted casemates line much of the courtyard’s perimeter. These vaulted chambers were spacious enough to allow carriages to enter and maneuver, suggesting multifunctional use ranging from storage to protection of goods and personnel.

Beneath the castle, an extensive network of wide underground tunnels and hiding places was constructed. These subterranean spaces functioned as shelters during sieges and served to store food supplies and ammunition, reflecting the castle’s preparedness for prolonged defense.

Two notable palatial residences stand inside the fortress. The Ostrogski Palace occupies the southern part of the enclosure. Its date of construction and designer remain unclear, but it retains fragments of medieval ornamental decoration above its first floor, indicating its early origins. On the northern side, the Lubomirski Palace was rebuilt in the late 18th century, likely under architect Henryk Ittar. Its exterior is modest, yet internally it preserves fine classical friezes and heraldic symbols that reflect its noble occupants’ status. Additionally, a smaller Karwacki palace from the same period is located along the southern curtain wall, adding to the site’s residential complexity.

Historically, the castle’s armory was well equipped, hosting 73 cannons in the 16th century and maintaining a foundry capable of producing firearms ranging from muskets and falconets to more modern rifles and machine guns over time, illustrating the site’s ongoing military significance.

Defensive features include a steep, vertical retaining wall composed of rough stone lining the castle’s side facing the town, enhancing resistance to assault. The bastions also contain casemates that connect internally to the surrounding fortifications, allowing defenders to move and operate artillery under cover.

Today, Dubno Castle remains largely preserved and is undergoing restoration efforts. The grounds remain well maintained, supporting its role as a historical museum and cultural venue, while its robust structures continue to convey the site’s strategic importance through the centuries.