Cuma Archaeological Park: An Ancient Greek and Roman Site in Southern Italy

Table of Contents

Visitor Information

Google Rating: 4.5

Popularity: Medium

Google Maps: View on Google Maps

Official Website: pafleg.cultura.gov.it

Country: Italy

Civilization: Byzantine, Greek, Roman

Remains: Burial, City, Civic, Domestic, Economic, Entertainment, Infrastructure, Military, Religious, Sanitation

Context

Cuma Archaeological Park is situated near Pozzuoli in the Campania region of southern Italy, occupying a prominent coastal promontory overlooking the Tyrrhenian Sea. The site’s elevated plateau, composed primarily of volcanic tuff, offers natural defensive advantages and commanding views over the surrounding plains and coastline. Its location near the Bay of Naples and within the volcanic Phlegraean Fields shaped settlement patterns, resource availability, and urban development throughout its history.

First established by Greek colonists from Euboea in the 8th century BCE, Cuma’s strategic position facilitated maritime trade and cultural exchange across the Gulf of Naples. The surrounding landscape, marked by volcanic activity and fertile soils, influenced both prosperity and periods of decline, as eruptions and seismic events periodically disrupted habitation. The site’s occupation extended through Greek, Samnite, Roman, and early medieval phases, with archaeological remains preserved in part due to the protective qualities of the volcanic terrain. Ongoing conservation efforts aim to stabilize exposed ruins and maintain the archaeological context for research and education.

History

Cuma Archaeological Park represents one of the earliest and most significant Greek colonial foundations in Italy, with a continuous occupation spanning from indigenous prehistory through late antiquity. Its development reflects complex interactions among indigenous populations, Greek settlers, Italic peoples, and Roman imperial authorities. The site’s coastal promontory and natural fortifications underpinned its military and political roles in the Bay of Naples region. Over time, Cuma transitioned from a Greek polis to a municipium within the Roman state, later becoming an early Christian center before its decline and abandonment in the medieval period following Saracen incursions.

Indigenous and Early Iron Age Settlement (Late Bronze Age – Early Iron Age)

Prior to Greek colonization, the area of Cuma was inhabited by indigenous communities during the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age. Archaeological investigations of necropolises have uncovered cremation tombs containing grave goods such as weapons, personal ornaments, and utilitarian objects, attesting to established burial customs and a settled population. These early inhabitants occupied the site before the arrival of Greek colonists, indicating a long-standing human presence that laid foundational cultural and demographic elements for subsequent urbanization.

Greek Colonization and Archaic Period (circa 730 BCE – 5th century BCE)

According to ancient tradition, around 730 BCE, Greek settlers from Chalcis in Euboea founded Cuma by displacing the indigenous village and establishing a fortified city on a steep tuff promontory. This location provided natural defenses, with the acropolis perched approximately 80 meters above sea level and accessible primarily from the south. The colony rapidly expanded its influence, founding satellite settlements such as Baia, Pozzuoli, Naples, Miseno, and Capri, thereby exerting control over the Gulf of Naples. Cuma engaged in military conflicts with the Etruscans, securing notable victories in 524 BCE and a naval battle in 474 BCE, which reinforced its regional dominance.

The city emerged as a significant commercial and cultural center, disseminating the Chalcidian alphabet that influenced Italic scripts, including Etruscan and Latin. Defensive structures from the 6th century BCE, constructed in isodomic masonry of yellow tuff with brick and marble inserts, fortified the acropolis. Public architecture included the Temple of Apollo, originally built in the Greek or early Samnite period, featuring an Ionic peripteral colonnade and an adjacent rectangular cistern for water supply. Maritime infrastructure comprised at least one natural harbor at the acropolis’s base and possibly a second within the now-drained Licola lagoon, facilitating trade and communication. Necropolises from this period contain cremation burials with bronze urns and rich grave goods such as silver fibulae, weapons, and spindles, alongside limited ceramic imports including Attic red-figure pottery dated to the 6th–5th centuries BCE.

Samnite Conquest and Sannitic Period (421 BCE – 338 BCE)

Political instability within Cuma culminated in its conquest by the Samnites in 421 BCE. This transition introduced Italic cultural elements and expanded the urban footprint beyond the acropolis toward the coastal plain. Architectural remains from this period exhibit early Roman building techniques, reflecting evolving construction practices. Burial customs diversified, with cist graves constructed from tuff slabs and chamber tombs occasionally adorned with frescoes. Grave goods include red-figure and black-gloss pottery as well as gold and silver artifacts, indicating artisanal production and wealth accumulation. The Samnite period represents a phase of urban expansion and cultural integration that set the stage for subsequent Roman incorporation.

Roman Conquest and Republican Period (338 BCE – 1st century BCE)

In 338 BCE, Cuma was incorporated into the Roman Republic and granted municipium status, recognizing its alliance during the Punic Wars. Despite formal integration, the city experienced gradual decline, influenced by environmental challenges such as surrounding marshlands that hindered expansion and health. Roman infrastructural developments included the construction of the Via Domitiana in 95 CE, which improved connectivity between Pozzuoli and Rome. This road passed near Cuma and was marked by the Arco Felice, a monumental double-arched viaduct built into the tuff cliffs of Monte Grillo.

The Roman lower city expanded significantly, featuring a forum constructed between the late 2nd and early 1st centuries BCE. The forum measured approximately 120 by 50 meters and was bordered by two-story tuff porticoes with Corinthian columns and Doric friezes. Central civic and religious buildings included the Temple of Jupiter, the Capitolium, and public baths. Commercial tabernae and a monumental fountain adorned the forum, while nearby structures in opus reticulatum with apses likely served as a basilica. The port, rebuilt under Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, was connected by a canal to Lake Fusaro and included docks, a careening basin, and a probable lighthouse. However, competition from neighboring ports such as Miseno and Pozzuoli led to its decline. Religious architecture evolved with major temples undergoing Augustan modifications and later Christian conversions, reflecting shifting religious landscapes.

Imperial Roman Period (1st century BCE – 5th century CE)

During the Imperial era, Cuma sustained and enhanced its public infrastructure. The forum and baths were restored and expanded into the 3rd century CE. The Baths of the Forum featured complex heating systems, including frigidarium, tepidarium, sudatio, and calidarium rooms supplied by a large cistern divided into four tanks. The Central Baths, originally constructed in the 3rd–2nd centuries BCE and modified in the 1st century BCE, included vaulted rooms and were adapted for changing and bathing functions. The amphitheater, built in the late Republic and refurbished in the 2nd century CE, hosted public spectacles before its late-antique conversion to ceramic production, evidenced by kilns installed within the structure.

The Temple of Isis, discovered near the acropolis and dating from the 1st century BCE to the 1st century CE, was active until the 2nd century CE when it was destroyed, likely due to Christian opposition. This temple was larger than its counterpart in Pompeii and contained finely painted floors and a basin with statuettes of Isis, a sphinx, and a priestess with Osiris, all deliberately defaced. The religious landscape shifted as pagan temples were converted into Christian basilicas, reflecting broader imperial religious transformations during this period.

Late Antiquity and Christianization (4th – 6th centuries CE)

The ascendancy of Christianity brought profound changes to Cuma’s urban and religious fabric. Pagan temples such as those dedicated to Jupiter and Apollo were repurposed as Christian basilicas, incorporating baptisteries and burial spaces within their floors. The Antro della Sibilla, a vaulted tuff gallery approximately 130 meters long, traditionally identified as the Sibyl’s cave, was likely adapted during this period, though its original function remains uncertain and may have been defensive. The Crypta Romana, a 300-meter-long tunnel constructed in the Augustan age to connect the port with the lower city beneath the acropolis, remained in use until the 2nd century CE before partial collapse. Subsequently, the intact sections were converted into a paleochristian necropolis. Byzantine restoration efforts followed the Gothic Wars, but the city’s prominence diminished. Cuma became a notable center of early Christianity in Campania, associated with early Christian texts such as “The Shepherd of Hermas” and ecclesiastical activity.

Byzantine, Lombard, and Saracen Periods (6th – early 13th centuries CE)

Between 542 and 553 CE, Cuma was contested during the Gothic Wars, passing from Ostrogothic to Byzantine control. In 558 CE, the Byzantine fleet prefect Flavius Nonius Erastus fortified the city. From the early 8th century, Lombard rule extended over the area, with governance alternating between the Duchies of Benevento and Naples. Saracen pirates later occupied the acropolis, exploiting its tunnels as refuge and bases for raids in the Gulf of Naples. In 1207 CE, Neapolitan forces led by Goffredo di Montefuscolo destroyed Cuma to eliminate the Saracen threat, effectively ending its historical continuity as an inhabited center. Following this destruction, many inhabitants and clergy relocated to Giugliano, transferring religious cults such as those of Saint Maximus and Saint Juliana. The lower city area became increasingly marshy due to silting and river course changes, leading to abandonment.

Modern Rediscovery and Archaeological Investigations (17th century – present)

Interest in Cuma’s ruins dates to the 17th century, attracting literary figures such as Francesco Petrarca and Jacopo Sannazaro, who referenced the site in their works. Initial excavations began in 1606, uncovering statues and marble reliefs, including a colossal statue of Jupiter now housed in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples. Systematic archaeological investigations commenced in 1852 under Prince Leopold of the Two Sicilies, focusing on the Masseria del Gigante area and necropolises. Emilio Stevens conducted extensive necropolis excavations between 1878 and 1893, though his methods led to significant looting and loss of context. Further damage occurred during drainage works at Lake Licola in the early 20th century.

Excavations of the acropolis began in 1911, revealing the Temple of Apollo, while Amedeo Maiuri and Vittorio Spinazzola investigated the Temple of Jupiter, the Sibyl’s Cave, and the Crypta Romana between 1924 and 1934. Exploration of the lower city took place from 1938 to 1953, followed by restoration projects including the Sibyl’s Tomb and the Capitolium. The 1992 discovery of the Temple of Isis near the beach expanded knowledge of the site’s religious architecture. The “Kyme” project, initiated in 1994, enhanced site preservation and completed excavations of a tholos tomb, city walls, the forum area, and maritime villas. Artifacts from Cuma are primarily curated in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples and the Archaeological Museum of the Phlegraean Fields.

Daily Life and Importance by Period

Greek Colonization and Archaic Period (circa 730 BCE – 5th century BCE)

Following the establishment of Cuma by Greek colonists from Chalcis, the population was predominantly Greek, organized into family-based households with social stratification including aristocratic elites, artisans, and laborers. Men engaged in public, military, and commercial activities, while women managed domestic affairs. Economic life centered on maritime trade, agriculture, and craft production. The city’s natural harbor facilitated exchange of goods such as olive oil, wine, and pottery. Archaeological evidence of cisterns and water management systems indicates organized urban infrastructure supporting daily needs. Workshops producing ceramics and metal goods likely operated at household or small-scale levels. Diet consisted of Mediterranean staples including cereals, olives, fish, and local fruits. Domestic interiors featured mosaic floors and painted walls, while public spaces such as the agora and temples served religious and civic functions. Religious practices focused on Greek deities, with festivals and rituals held in temples on the acropolis. Civic organization included magistrates and councils, though specific inscriptions from this period are limited. The city’s fortifications and urban planning reflect a community invested in defense and structured governance.

Samnite Conquest and Sannitic Period (421 BCE – 338 BCE)

The Samnite conquest introduced Italic cultural elements and expanded the urban area beyond the acropolis to the coastal plain. The population became ethnically mixed, incorporating Samnite settlers alongside local inhabitants. Social hierarchy evolved to include new elites aligned with Samnite governance, while traditional Greek families likely retained influence. Economic activities diversified, emphasizing agriculture and early Roman-style building techniques evident in domestic and public architecture. Tomb findings with decorated pottery and precious metals suggest artisanal crafts and wealth accumulation. Household economies combined farming, animal husbandry, and localized manufacturing, possibly including textile production and metalworking. Diet remained Mediterranean but may have incorporated more locally sourced products. Domestic spaces likely featured simpler decoration compared to the Greek period, with chamber tomb frescoes indicating evolving funerary customs. Transport and trade persisted, though the city’s regional dominance waned. Religious life blended Greek and Italic traditions, with new cult practices emerging. Social customs adapted to Samnite norms, and political authority was exercised by local Samnite officials. This period laid the groundwork for Roman integration by expanding urban areas and modifying civic institutions.

Roman Conquest and Republican Period (338 BCE – 1st century BCE)

Under Roman rule, Cuma was granted municipium status, incorporating Roman administrative frameworks alongside existing local traditions. The population included Roman settlers, local Samnites, and Greek descendants, forming a culturally heterogeneous community. Inscriptions attest to civic officials such as duumviri overseeing municipal governance. Economic life shifted toward integration with Roman trade networks. Agriculture remained vital, with grain, olives, and vines cultivated in surrounding lands. The construction of the Via Domitiana and the Arco Felice viaduct improved connectivity, facilitating movement of goods and people. The port, rebuilt by Agrippa, supported maritime commerce, though competition reduced its prominence over time. Diet continued to emphasize bread, olives, fish, and wine, supplemented by imported goods available in the forum’s tabernae. Domestic architecture featured multi-room houses with courtyards, decorated with frescoes and mosaic floors. Public amenities such as baths and basilicas reflected Roman urban standards and social life. Religious practices evolved as pagan temples dedicated to Jupiter and Apollo were maintained and later adapted. Civic life included public assemblies and legal proceedings in the forum. Social stratification encompassed landowning elites, merchants, artisans, freedmen, and slaves, with family structures typical of Roman society.

Imperial Roman Period (1st century BCE – 5th century CE)

Cuma’s population stabilized under Imperial rule, maintaining a blend of Romanized locals and immigrant families. Social hierarchy remained pronounced, with elites sponsoring public works and religious institutions. Inscriptions and architectural remains indicate continued municipal administration and religious leadership. Economic activities included agriculture, artisanal production, and service industries. The Baths of the Forum and Central Baths exemplify advanced engineering and public health infrastructure, serving both hygienic and social functions. The amphitheater hosted spectacles until its late-antique conversion to ceramic production, reflecting economic adaptation. Dietary remains confirm continued consumption of Mediterranean staples, with evidence of fish and olive oil production. Domestic interiors featured vaulted rooms, mosaic decoration, and functional spaces such as kitchens and storage. Trade networks supplied imported luxury goods alongside local products. Religious life transitioned markedly as pagan temples were converted into Christian basilicas. The Temple of Isis, active until the 2nd century CE, illustrates religious diversity prior to Christian dominance. Educational and cultural activities likely included Christian catechesis and public readings, though direct evidence is limited. Cuma functioned as a municipium with civic institutions adapting to imperial and religious transformations.

Late Antiquity and Christianization (4th – 6th centuries CE)

The rise of Christianity reshaped Cuma’s social and urban fabric. The population increasingly identified as Christian, with clergy assuming prominent roles. Pagan temples were repurposed as basilicas with baptisteries and burial spaces, reflecting new religious practices and community organization. Economic life contracted but maintained essential functions, with some public buildings partially abandoned or converted for alternative uses. The Crypta Romana tunnel’s reuse as a paleochristian necropolis exemplifies adaptive reuse of infrastructure. Household structures likely became simpler, focusing on subsistence and ecclesiastical patronage. Diet and clothing remained consistent with Mediterranean traditions, though archaeological evidence is sparse. Transport and trade diminished due to regional instability and environmental challenges. Educational activities centered on Christian instruction and liturgical gatherings, positioning Cuma as an early Christian center in Campania. Administratively, Byzantine restoration efforts reinforced fortifications and ecclesiastical authority. The city’s role shifted from a commercial hub to a religious and defensive outpost within the late Roman and early Byzantine world.

Byzantine, Lombard, and Saracen Periods (6th – early 13th centuries CE)

Following Gothic and Byzantine conflicts, Cuma’s population declined and became militarized under Byzantine and later Lombard control. Social structures adapted to wartime conditions, with ecclesiastical leaders and military governors prominent. The acropolis served as a fortified refuge during Saracen raids. Economic activity was limited, focused on local agriculture and sporadic trade. The lower city’s abandonment due to marsh formation reduced urban density. Domestic life was constrained by insecurity, with simpler housing and reduced public amenities. Religious life remained Christian, with transferred cults and clergy relocating after the city’s destruction in 1207 CE. Educational and cultural activities likely persisted in ecclesiastical contexts but were curtailed by conflict. Cuma’s regional importance diminished, ending its historical continuity as an inhabited center. This period marks the final phase of occupation before the site’s transition into archaeological ruins.

Remains

Architectural Features

Cuma Archaeological Park encompasses an elevated plateau with archaeological remains spanning from the Greek Archaic period through late antiquity. The site’s urban layout includes a fortified acropolis atop a tuff hill and an expanded lower city on the adjacent coastal plain. The acropolis was originally enclosed by substantial fortifications dating to the 6th century BCE, consisting of three rows of yellow tuff blocks arranged in isodomic masonry with brick and marble inserts. These walls survive primarily on the southeast side and likely incorporated a gate providing access to roads leading toward Pozzuoli and Miseno. The lower city was also enclosed by defensive walls, though only fragments remain. The monumental Arco Felice, constructed in 95 CE, served as a grand entrance for the Via Domitiana, connecting Cuma to the Roman road network. This arch stands approximately 20 meters high and 6 meters wide, formed by two superimposed arches creating a viaduct between tuff cliffs of Monte Grillo. The arch’s piers contain niches that once housed statues, some of which survive in altered form.

The site includes an extensive network of subterranean passages. The Crypta Romana, built in the Augustan age by Lucius Cocceius Auctus, is a roughly 300-meter-long tunnel linking the port area to the lower city beneath the acropolis. It remained in use until the 2nd century CE before partial collapse blocked sections; the intact portion was later adapted as a paleochristian necropolis. Byzantine restoration followed, but the tunnel suffered damage during the Greco-Gothic wars in 552 CE. The Grotta di Cocceio, constructed contemporaneously, extends about one kilometer, connecting the port of Cuma with the port on Lake Lucrino. It varies between 5 and 6 meters in width and is illuminated by six vertical shafts. Portions remain unexplored, particularly a branch toward the amphitheater, and the tunnel partially collapsed during World War II due to stored ordnance explosions.

Key Buildings and Structures

Forum

The Forum is located in the lower city and was constructed between the late 2nd and early 1st centuries BCE. It measures approximately 120 meters in length and 50 meters in width. The north and south sides are lined with two-story porticoes built of tuff, featuring Corinthian columns and pilasters. These porticoes are decorated with Doric friezes of triglyphs and metopes covered in white stucco, stylistically dated to the Sullan period. The paved floor is slightly inclined and was lowered to accommodate a temple and to channel rainwater into drainage systems. The square contained a monumental fountain and was surrounded by numerous tabernae used for commercial activities. Central to the Forum is the Temple of Jupiter; the Capitolium is situated on the southern side, and the Baths of the Forum lie to the northwest. Adjacent walls constructed in reticulated masonry with an apse likely belong to a basilica structure.

Temple of Jupiter

Situated atop the acropolis, the Temple of Jupiter dates to the 6th century BCE. Excavations conducted between 1924 and 1932 revealed foundations composed of large tuff blocks, though only partial remains survive, including a collapsed western side. During the Augustan period, the temple’s footprint was reduced to the central portion of its base. Between the 5th and 6th centuries CE, it was converted into a Christian basilica, with the presbytery located inside the original cella. Behind the cella is a marble-clad baptismal font with three steps designed for full immersion, which remains well preserved. Floor tombs are also present within the converted structure.

Temple of Apollo

Discovered in 1912 and identified by an inscription referring to Apollo Cumano, this temple was constructed over an earlier building dating to the Greek or early Samnite period. It features an Ionic peripteral colonnade and traces of a low tuff podium. In the Augustan era, a pronaos (front porch) and a tripartite cella (main chamber divided into three parts) were added. Between the 6th and 7th centuries CE, the temple was converted into a Christian basilica; a baptismal font and floor tombs from this phase remain visible.

Temple of Artemis

Located near the Temple of Apollo and oriented similarly, the Temple of Artemis dates to the late Republican period. The structure is identified as a sacred building, though its specific dedication remains uncertain. Only partial remains survive, with limited architectural details documented.

Temple of Isis

Discovered in 1992 on the beach in front of the acropolis, the Temple of Isis dates from the 1st century BCE to the 1st century CE. It was in use until the 2nd century CE when it was destroyed, likely due to Christian opposition. The temple is larger than the contemporary Temple of Isis at Pompeii and consists of a podium with remains of flooring and finely executed wall paintings. A basin within the temple contained three statuettes representing Isis, a sphinx, and a priestess with Osiris; all statuettes have broken heads, possibly due to iconoclastic acts. These artifacts are now housed in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples.

Building at Masseria del Gigante

Initially misidentified as the Temple of Jupiter, this building dates to the 1st century BCE and remains largely unexcavated. It served as the seat of magistrates and the senate. The structure includes a staircase leading to a podium with a central cella featuring an absidal (semi-circular) rear wall. The building is extensively covered in marble. Its name derives from the nearby discovery of a colossal statue of Jupiter.

Temple with Portico

Located in the southern part of the Forum, this temple was constructed during the Julio-Claudian period. It is surrounded on three sides by a portico with 24 columns, though only the bases and travertine pavement survive. The portico terminates with two apses retaining traces of white, yellow, and red paint. The temple proper consists of a podium, pronaos, and an absidal cella housing a base for an honorary statue. The deity worshiped here is unknown; hypotheses include Hera, Demeter (supported by an inscription), Vespasian, or the Augustales.

Small Extra-Urban Temple near Amphitheater

Discovered in 1842 and incorporated into Villa Vergiliana in 1911, this small temple site yielded Greek terracotta fragments, indicating the presence of a previous Greek temple. The remains are limited and fragmentary.

Baths of the Forum

Constructed in the 2nd century BCE during the Republican period, the Baths of the Forum were restored and expanded into the 3rd century CE. They were partially abandoned by the 5th century CE and later partly reused as dwellings or storage spaces. The complex includes two entrances: one leading to the palestra (exercise area) and another to the vestibule. The vestibule provides access to the frigidarium (cold room) via a colonnaded corridor and to the tepidarium (warm room), which leads to the sudatio (sweating room) and calidarium (hot room). The calidarium contains three basins. Water was supplied by a large cistern divided into four tanks. The rooms feature vaulted ceilings, including cross vaults and barrel vaults, with lighting through windows in the vaults. Finds include marble slabs, black and white tessellated mosaics, stucco remains, and porphyry cornices.

Central Baths (Erroneously called Sibyl’s Tomb)

Constructed between the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE and modified in the 1st century BCE, this bath complex was discovered at the end of the 18th century. It comprises a large rectangular room with a barrel vault made of mixed masonry and tuff. Traces of frescoes are present. Initially used as a changing room, evidenced by niches for clothes, it was converted in the Imperial period into a tepidarium by adding a niche with a basin for ablutions and skylights in the vault. Additional rooms include a corridor with barrel vaults and a cistern coated with cocciopesto (waterproof mortar). Finds include marble slabs, stucco fragments, and a marble base for a labrum (washbasin). The structure is partly buried under debris and vegetation.

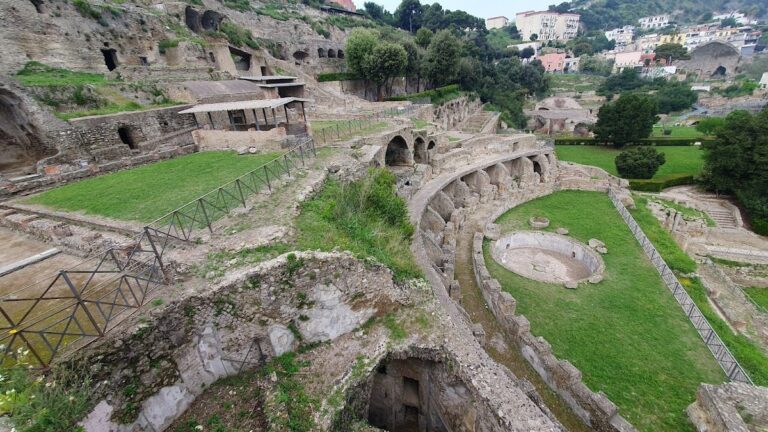

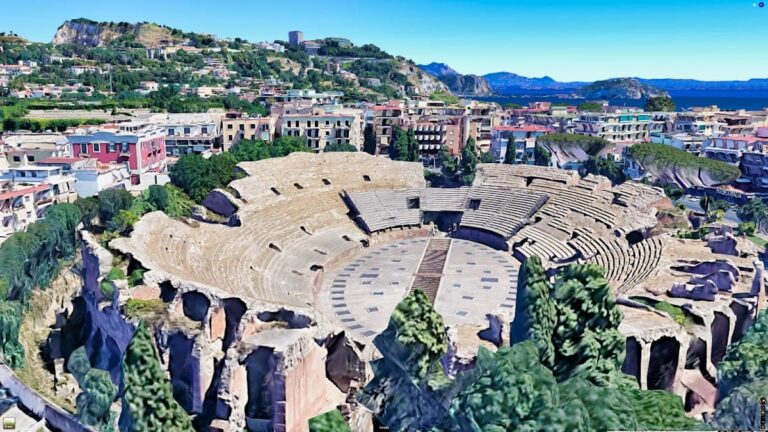

Amphitheater of Cuma

Located outside the city walls, the amphitheater was constructed between the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE and restored in the 2nd century CE. By the 5th to 6th centuries CE, it lost its original function and was repurposed for ceramic production, with furnaces installed inside. Currently, only the arches of the summa cavea (upper seating area) remain almost entirely preserved. The major axis measures about 90 meters. Entrances were likely located on the north and east sides. The seating was stripped of marble cladding in antiquity.

Capitolium

Located centrally within the Forum in the lower city, the Capitolium was built in the 3rd century BCE and fully restored during the Imperial period. Originally dedicated solely to Jupiter until the 2nd century BCE, it was later rededicated to the Capitoline Triad. The building measures 57 meters in length and 28 meters in width and follows an Italic plan with a pronaos and three internal naves. Marble fragments suggest a Corinthian order. Three heads of cult statues from the Imperial age were found on site.

Antro della Sibilla

Discovered in 1932 by Amedeo Maiuri, the Antro della Sibilla is a vaulted gallery approximately 130 meters long, entirely excavated in tuff and trapezoidal in shape. At its end is a vaulted chamber with three niches; the right niche is larger and resembles a small room likely closed by a gate, as indicated by post holes on the walls. No definitive evidence confirms its use for divination; some scholars propose it served a defensive function.

Necropolises

The necropolises extend over an area approximately three kilometers long and contain tombs from Greek, Samnite, and Roman periods. Early tombs excavated between 1852 and 1857 yielded grave goods such as weapons, pottery, and personal items, though many were lost due to poor excavation methods. Samnite tombs include cist graves constructed with tuff slabs and chamber tombs with small frescoes. Grave goods comprise red-figure and black-gloss pottery, gold and silver artifacts. A notable tholos tomb excavated in 1902 has a circular plan with a conical vault and internal niches. The Roman necropolis includes the Mausoleum of the Wax Heads, discovered in 1853, made of tuff and bricks; it contained four skeletons whose heads were replaced with wax masks. Cremation burials for wealthy individuals were common, with ashes placed in bronze cauldrons inside tuff containers, accompanied by silver fibulae, weapons, and spindles. Ceramic finds are scarce except for some from southern Etruria and Attic red-figure pottery dated to the 6th–5th centuries BCE. The necropolises suffered heavy looting, with most finds now housed in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples.

Other Remains

Surface traces of a rectangular cistern near the Temple of Apollo date from the 6th to 5th centuries BCE; it is partially collapsed with an unknown roof and entrance. Remains of three maritime villas have been found along the coastline. Near the exit of the Crypta Romana, archaeological remains include docks, a careening basin, an 8-meter-high tuff block in reticulated masonry, and a long wall with buttresses possibly serving as a lighthouse. The exact location of the ancient port remains uncertain, with hypotheses including a Greek port at the foot of the acropolis and two ports inside the now-drained Lake Licola. The port declined after the Samnite conquest in 421 BCE and was rebuilt by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa during Roman times, connected by a canal to Lake Fusaro with a lock for desilting operations.

Archaeological Discoveries

Excavations at Cuma have uncovered a variety of artifacts spanning Greek, Samnite, and Roman periods. Pottery includes red-figure and black-gloss wares, with some imports from southern Etruria and Attica dated to the 6th and 5th centuries BCE. Inscriptions found on temples and public buildings provide dedicatory formulas, including references to Apollo Cumano and Demeter. Coins from various Roman emperors have been recovered, though specific dynasties are not detailed. Tools related to agriculture and crafts have been found in domestic and workshop contexts. Domestic objects such as lamps and cooking vessels appear in residential areas. Religious artifacts include statuettes of deities like Isis, sphinxes, and priestesses, as well as altars and ritual vessels. Many of these finds were discovered in sanctuaries, necropolises, and urban quarters. The majority of artifacts are curated in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples and the Archaeological Museum of the Phlegraean Fields.

Preservation and Current Status

The site’s fortifications, including the 6th-century BCE acropolis walls and the Arco Felice, are partially preserved, with the arch retaining its structural form and niches. The Crypta Romana and Grotta di Cocceio tunnels survive in varying states; the former is partially excavated and stabilized, while the latter remains partly unexplored and suffered damage during World War II. The Forum and associated temples retain substantial architectural elements, though some structures are fragmentary. The Temple of Jupiter and Temple of Apollo show partial remains with visible baptismal fonts and floor tombs from Christian conversions. The Baths of the Forum and Central Baths are preserved with vaulted rooms and mosaic floors, though some areas are buried or overgrown. The amphitheater’s upper arches survive, but seating and marble cladding are lost. The necropolises have been heavily looted, affecting preservation. Restoration efforts have stabilized key monuments such as the Sibyl’s Grotto and Capitolium, with ongoing conservation managed by the Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli.

Unexcavated Areas

Several areas within Cuma remain unexcavated or only partially explored. The Building at Masseria del Gigante, identified as the seat of magistrates and senate, is largely unexcavated. Portions of the Grotta di Cocceio tunnel, especially the branch leading to the amphitheater, remain unexplored. Surface surveys and historic maps suggest additional buried remains near the ancient port and along the coastline, though modern agricultural use limits investigation. The lower city’s full extent and some urban quarters await further excavation. Future archaeological work is constrained by conservation policies and modern land use, with some areas stabilized but left unexcavated to preserve the site’s integrity.